Robert Dawson: the first anthropologist of Aborigines?

The treatment of Aboriginal Australians in colonial times was generally atrocious. This is now well known and accepted by most. Until well into the 20th century, Aborigines were subjected to exploitation, abuse, and cold-blooded murder. They were regarded as sub-human, and they were not recognised at all as the traditional owners of their lands. For a long time, virtually no serious attempts were made to study or to understand their customs, their beliefs, and their languages. On the contrary, the focus was on "civilising" them by imposing upon them a European way of life, while their own lifestyle was held in contempt as "savage".

I recently came across a gem of literary work, from the early days of New South Wales: The Present State of Australia, by Robert Dawson. The author spent several years (1826-1828) living in the Port Stephens area (about 200km north of Sydney), as chief agent of the Australian Agricultural Company, where he was tasked with establishing a grazing property. During his time there, Dawson lived side-by-side with the Worimi indigenous peoples, and Worimi anecdotes form a significant part of his book (which, officially, is focused on practical advice for British people considering migration to the Australian frontier).

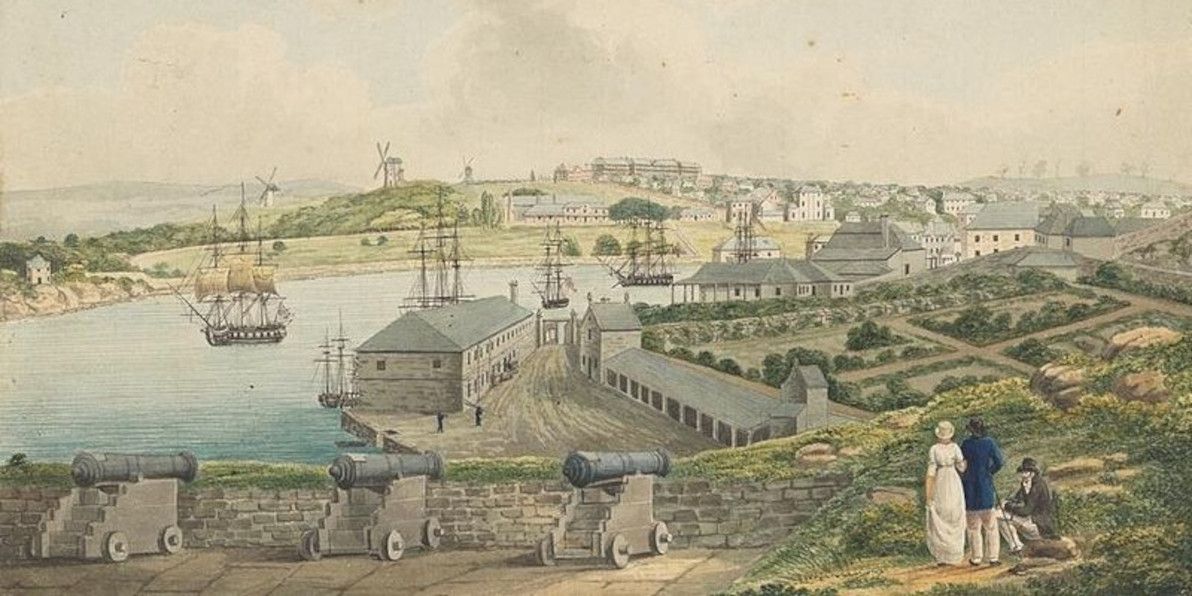

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

In this article, I'd like to share quite a number of quotes from Dawson's book, which in my opinion may well constitute the oldest known (albeit informal) anthropological study of Indigenous Australians. Considering his rich account of Aboriginal tribal life, I find it surprising that Dawson seems to have been largely forgotten by the history books, and that The Present State of Australia has never been re-published since its first edition in 1830 (the copies produced in 1987 are just fascimiles of the original). I hope that this article serves as a tribute to someone who was an exemplary exception to what was then the norm.

Language

The book includes many passages containing Aboriginal words interspersed with English, as well as English words spelt phonetically (and amusingly) as the tribespeople pronounced them; contemporary Australians should find many of these examples familiar, from the modern-day Aboriginal accents:

Before I left Port Stephens, I intimated to them that I should soon return in a "corbon" (large) ship, with a "murry" (great) plenty of white people, and murry tousand things for them to eat … They promised to get me "murry tousand bark." "Oh! plenty bark, massa." "Plenty black pellow, massa: get plenty bark." "Tree, pour, pive nangry" (three, four, five days) make plenty bark for white pellow, massa." "You come back toon?" "We look out for corbon ship on corbon water," (the sea.) "We tee, (see,) massa." … they sent to inform me that they wished to have a corrobery (dance) if I would allow it.

(page 60)

On occasion, Dawson even goes into grammatical details of the indigenous languages:

"Bael me (I don't) care." The word bael means no, not, or any negative: they frequently say, "Bael we like it;" "Bael dat good;" "Bael me go dere."

(page 65)

It's clear that Dawson himself became quite prolific in the Worimi language, and that – at least for a while – an English-Worimi "creole" emerged as part of white-black dialogue in the Port Stephens area.

Food and water

Although this is probably one of the better-documented Aboriginal traits from the period, I'd also like to note Dawson's accounts of the tribespeoples' fondness for European food, especially for sugar:

They are exceedingly fond of biscuit, bread, or flour, which they knead and bake in the ashes … but the article of food which appears most delicious to them, is the boiled meal of Indian corn; and next to it the corn roasted in the ashes, like chestnuts: of sugar too they are inordinately fond, as well as of everything sweet. One of their greatest treats is to get an Indian bag that has had sugar in it: this they cut into pieces and boil in water. They drink this liquor till they sometimes become intoxicated, and till they are fairly blown out, like an ox in clover, and can take no more.

(page 59)

Dawson also described their manner of eating; his account is not exactly flattering, and he clearly considers this behaviour to be "savage":

The natives always eat (when allowed to do so) till they can go on no longer: they then usually fall asleep on the spot, leaving the remainder of the kangaroo before the fire, to keep it warm. Whenever they awake, which is generally three or four times during the night, they begin eating again; and as long as any food remains they will never stir from the place, unless forced to do so. I was obliged at last to put a stop, when I could, to this sort of gluttony, finding that it incapacitated them from exerting themselves as they were required to do the following day.

(page 123)

Regarding water, Dawson gave a practical description of the Worimi technique for getting a drink in the bush in dry times (and admits that said technique saved him from being up the creek a few times); now, of course, we know that similar techniques were common for virtually all Aboriginal peoples across Australia:

It sometimes happens, in dry seasons, that water is very scarce, particularly near the shores. In such cases, whenever they find a spring, they scratch a hole with their fingers, (the ground being always sandy near the sea,) and suck the water out of the pool through tufts or whisps of grass, in order to avoid dirt or insects. Often have I witnessed and joined in this, and as often felt indebted to them for their example.

They would walk miles rather than drink bad water. Indeed, they were such excellent judges of water, that I always depended upon their selection when we encamped at a distance from a river, and was never disappointed.

(page 150)

Tools and weapons

In numerous sections, Dawson described various tools that the Aborigines used, and their skill and dexterity in fashioning and maintaining them:

[The old man] scraped the point of his spear, which was at least about eight feet long, with a broken shell, and put it in the fire to harden. Having done this, he drew the spear over the blaze of the fire repeatedly, and then placed it between his teeth, in which position he applied both his hands to straighten it, examining it afterwards with one eye closed, as a carpenter would do his planed work. The dexterous and workmanlike manner in which he performed his task, interested me exceedingly; while the savage appearance and attitude of his body, as he sat on the ground before a blazing fire in the forest, with a black youth seated on either side of him, watching attentively his proceedings, formed as fine a picture of savage life as can be conceived.

(page 16)

To the modern reader such as myself, Dawson's use of language (e.g. "a picture of savage life") invariably gives off a whiff of contempt and "European superiority". Personally, I try to give him the benefit of the doubt, and to brush this off as simply "using the vernacular of the time". In my opinion, this is fair justification for Dawson's manner of writing to some extent; but it also shows that he wasn't completely innocent, either: he too held some of the very views which he criticised in his contemporaries.

The tribespeople also exercised great agility in gathering the raw materials for their tools and shelters:

Before a white man can strip the bark beyond his own height, he is obliged to cut down the tree; but a native can go up the smooth branchless stems of the tallest trees, to any height, by cutting notches in the surface large enough only to place the great toe in, upon which he supports himself, while he strips the bark quite round the tree, in lengths from three to six feet. These form temporary sides and coverings for huts of the best description.

(page 19)

And they were quite dexterous in their crafting of nets and other items:

They [the women] make string out of bark with astonishing facility, and as good as you can get in England, by twisting and rolling it in a curious manner with the palm of the hand on the thigh. With this they make nets … These nets are slung by a string round their forehead, and hang down their backs, and are used like a work-bag or reticule. They contain all the articles they carry about with them, such as fishing hooks made from oyster or pearl shells, broken shells, or pieces of glass, when they can get them, to scrape the spears to a thin and sharp point, with prepared bark for string, gum for gluing different parts of their war and fishing spears, and sometime oysters and fish when they move from the shore to the interior.

(page 67)

Music and dance

Dawson wrote fondly of his being witness to corroborees on several occasions, and he recorded valuable details of the song and dance involved:

A man with a woman or two act as musicians, by striking two sticks together, and singing or bawling a song, which I cannot well describe to you; it is chiefly in half tones, extending sometimes very high and loud, and then descending so low as almost to sink to nothing. The dance is exceedingly amusing, but the movement of the limbs is such as no European could perform: it is more like the limbs of a pasteboard harlequin, when set in motion by a string, than any thing else I can think of. They sometimes changes places from apparently indiscriminate positions, and then fall off in pairs; and after this return, with increasing ardour, in a phalanx of four and five deep, keeping up the harlequin-like motion altogether in the best time possible, and making a noise with their lips like "proo, proo, proo;" which changes successively to grunting, like the kangaroo, of which it is an imitation, and not much unlike that of a pig.

(page 61)

Note Dawson's poetic efforts to bring to life the corroboree in words, with "bawling" sounds, "phalanx" movements, and "harlequin-like motion". Modern-day writers probably wouldn't bother to go to such lengths, instead assuming that their audience is familiar with the sights and sounds in question (at the very least, from TV shows). Dawson, who was writing for a Victorian English audience, didn't enjoy this luxury.

Families

In an era when most "white fellas" in the Colony were irrevocably destroying traditional Aboriginal family ties (a practice that was to continue well into the 20th century), Dawson was appreciating and making note of the finer details that he witnessed:

They are remarkably fond of their children, and when the parents die, the children are adopted by the unmarried men and women, and taken the greatest care of.

(page 68)

He also observed the prevalence of monogamy amongst the tribes he encountered:

The husband and wife are in general remarkably constant to each other, and it rarely happens that they separate after having considered themselves as man and wife; and when an elopement or the stealing of another man's gin [wife] takes place, it creates great, and apparently lasting uneasiness in the husband.

(page 154)

As well as the enduring bonds between parents and children:

The parents retain, as long as they live, an influence over their children, whether married or not – I then asked him the reason of this [separating from his partner], and he informed me his mother did not like her, and that she wanted him to choose a better.

(page 315)

Dawson made note of the good and the bad; in the case of families, he condoned the prevalence of domestic violence towards women in the Aboriginal tribes:

On our first coming here, several instances occurred in our sight of the use of this waddy [club] upon their wives … When the woman sees the blow coming, she sometimes holds her head quietly to receive it, much like Punch and his wife in the puppet-shows; but she screams violently, and cries much, after it has been inflicted. I have seen but few gins [wives] here whose heads do not bear the marks of the most dreadful violence of this kind.

(page 66)

Clothing

Some comical accounts of how the Aborigines took to the idea of clothing in the early days:

They are excessively fond of any part of the dress of white people. Sometimes I see them with an old hat on: sometimes with a pair of old shoes, or only one: frequently with an old jacket and hat, without trowsers: or, in short, with any garment, or piece of a garment, that they can get.

(page 75)

They usually reacted well to gifts of garments:

On the following morning I went on board the schooner, and ordered on shore a tomahawk and a suit of slop clothes, which I had promised to my friend Ben, and in which he was immediately dressed. They consisted of a short blue jacket, a checked shirt, and a pair of dark trowsers. He strutted about in them with an air of good-natured importance, declaring that all the harbour and country adjoining belonged to him. "I tumble down [born] pickaninny [child] here," he said, meaning that he was born there. "Belonging to me all about, massa; pose you tit down here, I gib it to you." "Very well," I said: "I shall sit down here." "Budgeree," (very good,) he replied, "I gib it to you;" and we shook hands in ratification of the friendly treaty.

(page 12)

Death and religion

Yet another topic which was scarcely investigated by Dawson's colonial peers – and which we now know to have been of paramount importance in all Aborigines' belief systems — rituals regarding death and mourning:

… when any of their relations die, they show respect for their memories by plastering their heads and faces all over with pipe-clay, which remains till it falls off of itself. The gins [wives] also burn the front of the thigh severely, and bind the wound up with thin strips of bark. This is putting themselves in mourning. We put on black; they put on white: so that it is black and white in both cases.

(page 74)

The Aborigines that Dawson became acquainted with, were convinced that the European settlers were re-incarnations of their ancestors; this belief was later found to be fairly widespread amongst Australia's indigenous peoples:

I cannot learn, precisely, whether they worship any God or not; but they are firm in their belief that their dead friends go to another country; and that they are turned into white men, and return here again.

(page 74)

Dawson appears to have debated this topic at length with the tribespeople:

"When he [the devil] makes black fellow die," I said, "what becomes of him afterwards?" "Go away Englat," (England,) he answered, "den come back white pellow." This idea is so strongly impressed upon their minds, that when they discover any likeness between a white man and any one of their deceased friends, they exclaim immediately, "Dat black pellow good while ago jump up white pellow, den come back again."

(page 158)

Inter-tribe relations

During his time with the Worimi and other tribes, Dawson observed many of the details of how neighbouring tribes interacted, for example, in the case of inter-tribal marriage:

The blacks generally take their wives from other tribes, and if they can find opportunities they steal them, the consent of the female never being made a question in the business. When the neighbouring tribes happen to be in a state of peace with each other, friendly visits are exchanged, at which times the unmarried females are carried off by either party.

(page 153)

In one chapter, Dawson gives an amusing account of how the Worimi slandered and villainised another tribe (the Myall people), with whom they were on unfriendly terms:

The natives who domesticate themselves amongst the white inhabitants, are aware that we hold cannibalism in abhorrence; and in speaking of their enemies, therefore, to us, they always accuse them of this revolting practice, in order, no doubt, to degrade them as much as possible in our eyes; while the other side, in return, throw back the accusation upon them. I have questioned the natives who were so much with me, in the closest manner upon this subject, and although they persist in its being the practice of their enemies, still they never could name any particular instances within their own knowledge, but always ended by saying: "All black pellow been say so, massa." When I have replied, that Myall black fellows accuse them of it also, the answer has been, "Nebber! nebber black pellow belonging to Port Tebens, (Stephens;) murry [very] corbon [big] lie, massa! Myall black pellows patter (eat) always."

(page 125)

The book also explains that the members of a given tribe generally kept within their own ancestral lands, and that they were reluctant and fearful of too-often making contact with neighbouring tribes:

… the two natives who had accompanied them had become frightened at the idea of meeting strange natives, and had run away from them about the middle of their journey …

(page 24)

Relations with colonists

Throughout the book, general comments are made that insinuate the fault and the aggression in general of "white fella" in the Colony:

The natives are a mild and harmless race of savages; and where any mischief has been done by them, the cause has generally arisen, I believe, in bad treatment by their white neighbours. Short as my residence has been here, I have, perhaps, had more intercourse with these people, and more favourable opportunities of seeing what they really are, than any other person in the colony.

(page 57)

Dawson provides a number of specific examples of white aggression towards the Aborigines:

The natives complained to me frequently, that "white pellow" (white fellows) shot their relations and friends; and showed me many orphans, whose parents had fallen by the hands of white men, near this spot. They pointed out one white man, on his coming to beg some provisions for his party up the river Karuah, who, they said, had killed ten; and the wretch did not deny it, but said he would kill them whenever he could.

(page 58)

Sydney

As a modern-day Sydneysider myself, I had a good chuckle reading Dawson's account of his arrival for the first time in Sydney, in 1826:

There had been no arrival at Sydney before us for three or four months. The inhabitants were, therefore, anxious for news. Parties of ladies and gentlemen were parading on the sides of the hills above us, greeting us every now and then, as we floated on; and as soon as we anchored, (which was on a Sunday,) we were boarded by numbers of apparently respectable people, asking for letters and news, as if we had contained the budget of the whole world.

(page 46)

Image source: Wikipedia.

No arrival in Sydney, from the outside world, for "three or four months"?! Who would have thought that a backwater penal town such as this, would one day become a cosmopolitan world city, that sees a jumbo jet land and take off every 5 minutes, every day of the week? Although, it seems that even back then, Dawson foresaw something of Sydney's future:

On every side of the town [Sydney] houses are being erected on new ground; steam engines and distilleries are at work; so that in a short time a city will rise up in this new world equal to any thing out of Europe, and probably superior to any other which was ever created in the same space of time.

(page 47)

And, even back then, there were some (like Dawson) who preferred to get out of the "rat race" of Sydney town:

Since my arrival I have spent a good deal of time in the woods, or bush, as it is called here. For the last five months I have not entered or even seen a house of any kind. My habitation, when at home, has been a tent; and of course it is no better when in the bush.

(page 48)

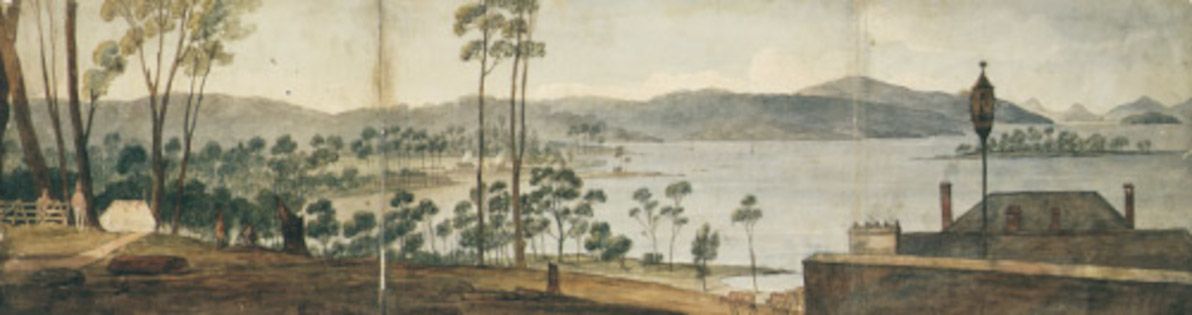

Image source: NSW National Parks.

There's still a fair bit of bush all around Sydney; although, sadly, not as much as there was in Dawson's day.

General remarks

Dawson's impression of the Aborigines:

I was much amused at this meeting, and above all delighted at the prompt and generous manner in which this wild and untutored man conducted himself towards his wandering brother. If they be savages, thought I, they are very civil ones; and with kind treatment we have not only nothing to fear, but a good deal to gain from them. I felt an ardent desire to cultivate their acquaintance, and also much satisfaction from the idea that my situation would afford me ample opportunities and means for doing so.

(page 11)

Nomadic nature of the tribes:

When away from this settlement, they appear to have no fixed place of residence, although they have a district of country which they call theirs, and in some part of which they are always to be found. They have not, as far as I can learn, any king or chief.

(page 63)

Tribal punishment:

I have never heard but of one punishment, which is, I believe, inflicted for all offences. It consists in the culprit standing, for a certain time, to defend himself against the spears which any of the assembled multitude think proper to hurl at him. He has a small target [shield] … and the offender protects himself so dexterously by it, as seldom to receive any injury, although instances have occurred of persons being killed.

(page 64)

Generosity of Aborigines (also illustrating their lack of a concept of ownership / personal property):

They are exceedingly kind and generous towards each other: if I give tobacco or any thing else to any man, it is divided with the first he meets without being asked for it.

(page 68)

Ability to count / reckon:

They have no idea of numbers beyond five, which are reckoned by the fingers. When they wish to express a number, they hold up so many fingers: beyond five they say, "murry tousand," (many thousands.)

(page 75)

Protocol for returning travellers in a tribe:

It is not customary with the natives of Australia to shake hands, or to greet each other in any way when they meet. The person who has been absent and returns to his friends, approaches them with a serious countenance. The party who receives him is the first to speak, and the first questions generally are, where have you been? Where did you sleep last night? How many days have you been travelling? What news have you brought? If a member of the tribe has been very long absent, and returns to his family, he stops when he comes within about ten yards of the fire, and then sits down. A present of food, or a pipe of tobacco is sent to him from the nearest relation. This is given and received without any words passing between them, whilst silence prevails amongst the whole family, who appear to receive the returned relative with as much awe as if he had been dead, and it was his spirit which had returned to them. He remains in this position perhaps for half an hour, till he receives a summons to join his family at the fire, and then the above questions are put to him.

(page 132)

Final thoughts

The following pages are not put forth to gratify the vanity of authorship, but with the view of communicating facts where much misrepresentation has existed, and to rescue, as far as I am able, the character of a race of beings (of whom I believe I have seen more than any other European has done) from the gross misrepresentations and unmerited obloquy that has been cast upon them.

(page xiii)

Dawson wasn't exactly modest, in his assertion of being the foremost person in the Colony to make a fair representation of the Aborigines; however, I'd say his assertion is quite accurate. As far as I know, he does stand out as quite a solitary figure for his time, in his efforts to meaningfully engage with the tribes of the greater Sydney region, and to document them in a thorough and (relatively) unprejudiced work of prose.

I would therefore recommend those who would place the Australian natives on the level of brutes, to reflect well on the nature of man in his untutored state in comparison with his more civilized brother, indulging in endless whims and inconsistencies, before they venture to pass a sentence which a little calm consideration may convince them to be unjust.

(page 152)

Dawson's criticism of the prevailing attitudes was scathing, although it was clearly criticism that was ignored and unheeded by his contemporaries.

It is not sufficient merely as a passing traveller to see an aboriginal people in their woods and forests, to form a just estimate of their real character and capabilities … To know them well it is necessary to see much more of them in their native wilds … In this position I believe no man has ever yet been placed, although that in which I stood approached more nearly to it than any other known in that country.

(page 329)

With statements like this, Dawson is inviting his fellow colonists to "go bush" and to become acquainted with an Aboriginal tribe, as he did. From others' accounts of the era, those who followed in his footsteps were few and far between.

I have seen the natives from the coast far south of Sydney, and thence to Morton Bay (sic), comprising a line of coast six or seven hundred miles; and I have also seen them in the interior of Argyleshire and Bathurst, as well as in the districts of the Hawkesbury, Hunter's River, and Port Stephens, and have no reason whatever to doubt that they are all the same people.

(page 336)

So, why has a man and a book with so much to say about early contact with the Aborigines, lain largely forgotten and abandoned by the fickle sands of history? Probably the biggest reason, is that Dawson was just a common man. Sure, he was the first agent of AACo: but he was no intrepid explorer, like Burke and Wills; nor an important governor, like Arthur Phillip or Lachlan Macquarie. While the diaries and letters of bigwigs like these have been studied and re-published constantly, not everyone can enjoy the historical limelight.

No doubt also a key factor, was that Dawson ultimately fell out badly with the powerful Macarthur family, who were effectively his employers during his time in Port Stephens. The Present State of Australia is riddled with thinly veiled slurs at the Macarthurs, and it's quite likely that this guaranteed the book's not being taken seriously by anyone, in the Colony or elsewhere, for a long time.

Dawson's work is, in my opinion, an outstanding record of indigenous life in Australia, at a time when the ancient customs and beliefs were still alive and visible throughout most of present-day NSW. It also illustrates the human history of a geographically beautiful region that's quite close to my heart. Like many Sydneysiders, I've spent several summer holidays at Port Stephens during my life. I've also been camping countless times at nearby Myall Lakes; and I have some very dear family friends in Booral, a small town which sits alongside the Karuah River just upstream from Port Stephens (and which also falls within Worimi country).

Image source: State Library of New South Wales.

In leaving as a legacy his narrative of the Worimi people and their neighbours (which is, as far as I know, the only surviving first-hand account of these people from the coloial era of any significance), I believe that Dawson's work should be lauded and celebrated. At a time when the norm for bush settlers was to massacre and to wreak havoc upon indigenous peoples, Dawson instead chose to respect and to make friends with those that he encountered.

Personally, I think the honour of "first anthropologist of the Aborigines" is one that Dawson can rightly claim (although others may feel free to dispute this). Descendants of the Worimi live in the Port Stephens area to this day; and I hope that they appreciate Dawson's tribute, as no doubt the spirits of their ancestors do.