Orientalists of the East India Company

The infamous East India Company, "the Company that Owned a Nation", is remembered harshly by history. And rightly so. On the whole, it was an exploitative venture, and the British individuals involved with it were ruthless opportunists. The Company's actions directly resulted in the impoverishment, the subjugation, and in several instances the death of countless citizens of the Indian Subcontinent.

Company rule, and the subsequent rule of the British Raj, are also acknowledged as contributing positively to the shaping of Modern India, having introduced the English language, built the railways, and established political and military unity. But these are overshadowed by its legacy of corporate greed and wholesale plunder, which continues to haunt the region to this day.

I recently read Four Heroes of India (1898), by F.M. Holmes, an antique book that paints a rose-coloured picture of Company (and later British Government) rule on the Subcontinent. To the modern reader, the book is so incredibly biased in favour of British colonialism that it would be hilarious, were it not so alarming. Holmes's four heroes were notable military and government figures of 18th and 19th century British India.

Image source: eBay.

I'd like to present here four alternative heroes: men (yes, sorry, still all men!) who in my opinion represented the British far more nobly, and who left a far more worthwhile legacy in India. All four of these figures were founders or early members of The Asiatic Society (of Bengal), and all were pioneering academics who contributed to linguistics, science, and literature in the context of South Asian studies.

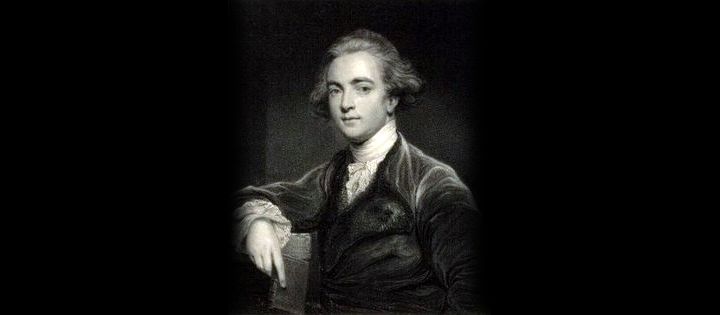

William Jones

The first of these four personalities was by far the most famous and influential. Sir William Jones was truly a giant of his era. The man was nothing short of a prodigy in the field of philology (which is arguably the pre-modern equivalent of linguistics). During his productive life, Jones is believed to have become proficient in no less than 28 languages, making him quite the polyglot:

Eight languages studied critically: English, Latin, French, Italian, Greek, Arabic, Persian, Sanscrit [sic]. Eight studied less perfectly, but all intelligible with a dictionary: Spanish, Portuguese, German, Runick [sic], Hebrew, Bengali, Hindi, Turkish. Twelve studied least perfectly, but all attainable: Tibetian [sic], Pâli [sic], Pahlavi, Deri …, Russian, Syriac, Ethiopic, Coptic, Welsh, Swedish, Dutch, Chinese. Twenty-eight languages.

Source: Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Correspondence, of Sir William Jones, John Shore Baron Teignmouth, 1806, Page 376.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Jones is most famous in scholarly history for being the person who first proposed the linguistic family of Indo-European languages, and thus for being one of the fathers of comparative linguistics. His work laid the foundations for the theory of a Proto-Indo-European mother tongue, which was researched in-depth by later linguists, and which is widely accepted to this day as being a language that existed and that had a sizeable native speaker population (despite there being no concrete evidence for it).

Jones spent 10 years in India, working in Calcutta as a judge. During this time, he founded The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Jones was the foremost of a loosely-connected group of British gentlemen who called themselves orientalists. (At that time, "oriental studies" referred primarily to India and Persia, rather than to China and her neighbours as it does today.)

Like his peers in the Society, Jones was a prolific translator. He produced the authoritative English translation of numerous important Sanskrit documents, including Manu Smriti (Laws of Manu), and Abhiknana Shakuntala. In the field of his "day job" (law), he established the right of Indian citizens to trial by jury under Indian jurisprudence. Plus, in his spare time, he studied Hindu astronomy, botany, and literature.

James Prinsep

The numismatist James Prinsep, who worked at the Benares (Varanasi) and Calcutta mints in India for nearly 20 years, was another of the notable British orientalists of the Company era. Although not quite in Jones's league, he was nevertheless an intelligent man who made valuable contributions to academia. His life was also unfortunately short: he died at the age of 40, after falling sick of an unknown illness and failing to recover.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Prinsep was the founding editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He is best remembered as the pioneer of numismatics (the study of coins) on the Indian Subcontinent: in particular, he studied numerous coins of ancient Bactrian and Kushan origin. Prinsep also worked on deciphering the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts; and he contributed to the science of meteorology.

Charles Wilkins

The typographer Sir Charles Wilkins arrived in India in 1770, several years before Jones and most of the other orientalists. He is considered the first British person in Company India to have mastered the Sanskrit language. Wilkins is best remembered as having created the world's first Bengali typeface, which became a necessity when he was charged with printing the important text A Grammar of the Bengal Language (the first book written in Bengali to ever be printed), written by fellow orientalist Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, and more-or-less commissioned by Governor Warren Hastings.

It should come as no surprise that this pioneering man was one of the founders of The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Like many of his colleagues, Wilkins left a proud legacy as a translator: he was the first person to translate into English the Bhagavad Gita, the most revered holy text in all of Hindu lore. He was also the first director of the "India Office Library".

H. H. Wilson

The doctor Horace Hayman Wilson was in India slightly later than the other gentlemen listed here, not having arrived in India (as a surgeon) until 1808. Wilson was, for a part of his time in Company India, honoured with the role of Secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Wilson was one of the key people to continue Jones's great endeavour of bridging the gap between English and Sanskrit. His key contribution was writing the world's first comprehensive Sanskrit-English dictionary. He also translated the Meghaduuta into English. In his capacity as a doctor, he researched and published on the matter of traditional Indian medical practices. He also advocated for the continued use of local languages (rather than of English) for instruction in Indian native schools.

The legacy

There you have it: my humble short-list of four men who represent the better side of the British presence in Company India. These men, and other orientalists like them, are by no means perfect, either. They too participated in the Company's exploitative regime. They too were part of the ruling elite. They were no Mother Teresa (the main thing they shared in common with her was geographical location). They did little to help the day-to-day lives of ordinary Indians living in poverty.

Nevertheless, they spent their time in India focused on what I believe were noble endeavours; at least, far nobler than the purely military and economic pursuits of many of their peers. Their official vocations were in administration and business enterprise, but they chose to devote themselves as much as possible to academia. Their contributions to the field of language, in particular – under that title I include philology, literature, and translation – were of long-lasting value not just to European gentlemen, but also to the educational foundations of modern India.

In recent times, the term orientalism has come to be synonymous with imperialism and racism (particularly in the context of the Middle East, not so much for South Asia). And it is argued that the orientalists of British India were primarily concerned with strengthening Company rule by extracting knowledge, rather than with truly embracing or respecting India's cultural richness. I would argue that, for the orientalists presented here at least, this was not the case: of course they were agents of British interests, but they also genuinely came to respect and admire what they studied in India, rather than being contemptuous of it.

The legacy of British orientalism in India was, in my opinion, one of the better legacies of British India in general. It's widely acknowledged that it had a positive long-term educational and intellectual effect on the Subcontinent. It's also a topic about which there seems to be insufficient material available – particularly regarding the biographical details of individual orientalists, apart from Jones – so I hope this article is useful to anyone seeking further sources.