Current state of the Cape to Cairo Railway

In the late 19th century, the British-South-African personality Cecil Rhodes dreamed of a complete, uninterrupted railway stretching from Cape Town, South Africa, all the way to Cairo, Egypt. During Rhodes's lifetime, the railway extended as far north as modern-day Zimbabwe – which was in that era known by its colonial name Rhodesia (in honour of Rhodes, whose statesmanship and entrepreneurism made its founding possible). A railway traversing the entire north-south length of Africa was an ambitious dream, for an ambitious man.

Rhodes's dream remains unfulfilled to this day.

"The Rhodes Colossus" illustration originally from Punch magazine, Vol. 103, 10 Dec 1892; image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Africa satellite image courtesy of Google Earth.

Nevertheless, significant additions have been made to Africa's rail network during the interluding century; and, in fact, only a surprisingly small section of the Cape to Cairo route remains bereft of the Iron Horse's footprint.

Although both information about – (a) the historical Cape to Cairo dream; and (b) the history / current state of the route's various railway segments – abound, I was unable to find any comprehensive study of the current state of the railway in its entirety.

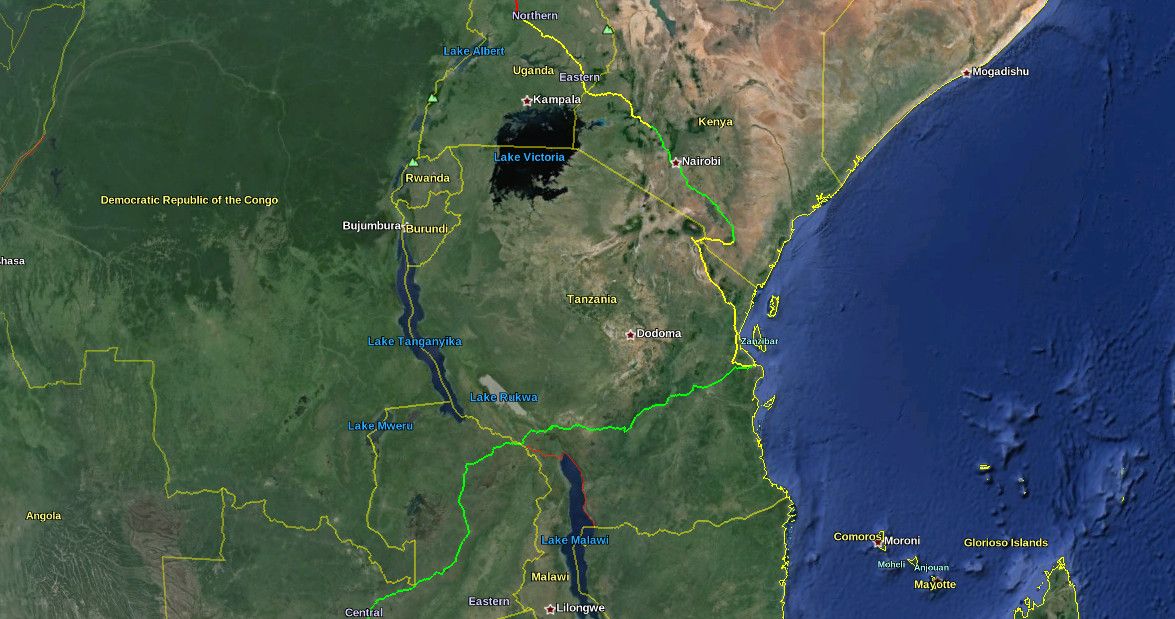

This article, therefore, is an endeavour to examine the current state of the full Cape to Cairo Railway. As part of this study, I've prepared a detailed map of the route, which marks in-service sections, abandoned sections, and missing sections. The map has been generated from a series of KML files, which I've made publicly available on GitHub, and for which I welcome contributions in the form of corrections / tweaks to the route.

Southern section

As its name suggests, the line begins in Cape Town, South Africa. The southern section of the railway encompasses South Africa itself, along with the nearby countries that have historically been part of the South African sphere of influence: that is, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Zambia.

The first segment – Cape Town to Johannesburg – is also the oldest, the best-maintained, and the best-serviced part of the entire route. The first train travelled this segment in 1892. There has been continuous service ever since. It's the only train route in all of Africa that can honestly claim to provide a "European standard" of passenger service, between the two major cities that it links. That is, there are numerous classes of service operating on the line – ranging from basic inter-city commuter trains, to business-style fast trains, to luxury sleeper trains – running several times a day.

So, the first leg of the railway is the one that we should be least worried about. Hence, it's marked in green on the map. This should come as no surprise, considering that South Africa has the best-developed infrastructure in all of Africa (by a long shot), as well as Africa's largest economy.

After Johannesburg, we continue along the railway that was already fulfilling Cecil Rhodes's dream before his death. This segment runs through modern-day Botswana, which was previously known as Bechuanaland Protectorate. From Johannesburg, it connects to the city of Mafeking, which was the capital of the former Bechuanaland Protectorate, but which today is within South Africa (where it is a regional capital). The line then crosses the border into Botswana, passes through the capital Gaborone, and continues to the city of Francistown in Botswana's north-east.

Unfortunately, since the opening of the Beitbridge Bulawayo Railway in Zimbabwe in 1999 (providing a direct train route between Zimbabwe and South Africa for the first time), virtually all regular passenger service on this segment (and hence, virtually all regular passenger service on Botswana's train network) has been cancelled. The track is still being maintained, and (apart from some freight trains) there are still occasional luxury tourist trains using the route. However, it's unclear if there are still any regular passenger services between Johannesburg and Mafeking (if there are, they're very few); and sources indicate that there are no regular passenger services at all between Mafeking and Francistown. Hence, the segment is marked in yellow on the map.

(I should also note that the new direct train route from South Africa to Zimbabwe, does actually provide regular passenger service, from Johannesburg to Messina, and then from Beitbridge to Bulawayo, with service missing only in the short border crossing between Messina and Beitbridge. However, I still consider the segment via Botswana to be part of the definitive "Cape to Cairo" route: because of its historical importance; and because only quite recently has service ceased on this segment and has an alternative segment been open.)

From Francistown onwards, the situation is back in the green. There is a passenger train from Francistown to Bulawayo, that runs three times a week. I should also mention here, that Bulawayo is quite a significant spot on the Cape to Cairo Railway, as (a) the grave of Cecil Rhodes can be found atop "World's View", a panoramic hilltop in nearby Matobo National Park; and (b) Bulawayo was the first city that the railway reached in (former) Rhodesia, and to this day it remains Zimbabwe's rail hub. Bulawayo is also home to a railway museum.

For the remainder of the route through Zimbabwe, the line remains in the green. There's a daily passenger service from Bulawayo to Victoria Falls. Sadly, this spectacular leg of the route has lost much of its former glory: due to Zimbabwe's recent economic and political woes, the trains are apparently looking somewhat the worse for wear. Nevertheless, the service continues to be popular and reasonably reliable.

The green is briefly interrupted by a patch of yellow, at the border crossing between Zimbabwe and Zambia. This is because there has been no passenger service over the famous Victoria Falls Bridge – which crosses the Zambezi River at spraying distance from the colossal waterfall, connecting the towns of Victoria Falls and Livingstone – more-or-less since the 1970s. Unless you're on board one of the infrequent luxury tourist trains that still traverse the bridge, it must be crossed on foot (or using local transport). It should also be noted that although the bridge is still most definitely intact and looking solid, it's more than 100 years old, and experts have questioned whether it's receiving adequate care and maintenance.

Image sourced from: Car Hire Victoria Falls.

Once in Zambia – formerly known as Northern Rhodesia – regular passenger services continue north to the capital, Lusaka; and from there, onward to the crossroads town of Kapiri Mposhi. It's here that the southern portion of the modern-day Cape to Cairo railway ends, since Kapiri Mposhi is the meeting-point of the colonial-era, British-built, South-African / Rhodesian railway network, and a modern-era East-African rail link that was unanticipated in Rhodes's plan.

I should also mention here that the colonial-era network continues north from Kapiri Mposhi, crossing the border with modern-day DR Congo (formerly known as the Belgian Congo), and continuing up to the shores of Lake Tanganyika, where it terminates at the town of Kalemie. The plan in the colonial era was that the Cape to Cairo passenger link would continue north via the Great Lakes in this region of Africa – in the form of lake / river ferries, up to Lake Albert, on the present-day DR Congo / Ugandan border – after which the rail link would resume, up to Egypt via Sudan.

However, I don't consider this segment to be part of the definitive "Cape to Cairo" route, because: (a) further rail links between the Great Lakes, up to Lake Albert, were never built; (b) the line running through eastern DR Congo, from the Zambian border to Kalemie on Lake Tanganyika, is apparently in serious disrepair; and (c) an alternative continuous rail link has existed, since the 1970s, via East Africa, and the point where this link terminates in modern-day Uganda is north of Lake Albert anyway. Therefore, the DR Congo – Great Lakes segment is only being mentioned here as an anecdote of history; and we now turn our attention to the East African network.

Eastern section

The Eastern section of the railway is centred in modern-day Tanzania and Kenya, although it begins and ends within the inland neighbours of these two coastal nations – Zambia and Uganda, respectively. This region, much like Southern Africa, was predominantly ruled under British colonialism in the 19th century (which is why Kenya, the region's hub, was formerly known as British East Africa). However, modern-day Tanzania (formerly called Tanganyika, before the union of Tanganyika with Zanzibar) was originally German East Africa, before becoming a British protectorate in the 20th century.

Kapiri Mposhi, in Zambia, is the start of the TAZARA Railway; this railway runs through the north-east of Zambia, crosses the border to Tanzania near Mbeya, and finishes on the Indian Ocean coast at Dar es Salaam, Tanzania's largest city.

The TAZARA is the newest link in the Cape to Cairo railway network: it was built and financed by the Chinese, and was opened in 1976. It's the only line in the network – and one of the only railway lines in all of Africa – that was built (a) by non-Europeans; and (b) in the post-colonial era. It was not envisioned by Rhodes (nor by his contemporaries), who wanted the line to pass through wholly British-controlled territory (Tanzania was still German East Africa in Rhodes's era). The Zambians wanted it, in order to alleviate their dependence (for international transport) on their southern neighbours Rhodesia and South Africa, with whom tensions were high in the 1970s, due to those nations' Apartheid governments. The line has been in regular operation since opening; hence, it's marked in green on the map.

Image source: Mzuzu Transit.

Although the TAZARA line doesn't quite touch the other Tanzanian railway lines that meet in Dar es Salaam, I haven't marked any gap in the route at Dar es Salaam. This is for two reasons. Firstly, from what I can tell (by looking at maps and satellite imagery), the terminus of the TAZARA in Dar es Salaam is physically separated from the other lines, by a distance of less than two blocks, i.e. a negligible amount. Secondly, the TAZARA is (as of 1998) physically connected to the other Tanzanian railway lines, at a junction near the town of Kidatu, and there is a cargo transshipment facility at this location. However, I don't believe there's any passenger service from Kidatu to the rest of the Tanzanian network (only cargo trains). So, the Kidatu connection is being mentioned here only as an anecdote; in my opinion, the definitive "Cape to Cairo" route passes through, and connects at, Dar es Salaam.

From Dar es Salaam, the line north is part of the decaying colonial-era Tanzanian rail network. This line extends up to the city of Arusha; the part that we're interested in ends at Moshi (east of Arusha), from where another line branches off, crossing the border into Kenya. Sadly, there has been no regular passenger service on the Arusha line for many years; therefore, nor is there any service to Moshi.

After crossing the Kenyan border, the route passes through the town of Taveta, before continuing on to Voi; here, there is a junction with the most important train line in Kenya: that which connects Mombasa and Nairobi. As with the Arusha line, the Moshi – Voi line has also been bereft of regular passenger service for many years. This entire portion of the rail network appears to be in a serious state of neglect. If there are any trains running in this area, they would be occasional freight trains; and if any track maintenance is being performed on these lines, it would be the bare minimum. Therefore, the full segment from Dar es Salaam to Voi is marked in yellow on the map.

From Voi, there are regular passenger services on the main Kenyan rail line to Nairobi; and onward from Nairobi, there are further passenger services (which appear to be less reliable, but regular nonetheless) to the city of Kisumu, which borders Lake Victoria. The part of this route that we're interested in ends at Nakuru (about halfway between Nairobi and Kisumu), from where another line branches off towards Uganda. The route through Kenya, from Voi to Nakuru, is therefore in the green.

After Nakuru, the line meanders its way towards the Ugandan border; and at Tororo (a city on the Ugandan side), it connects with the Ugandan network. There is apparently no longer any passenger service available from Nakuru to Tororo – i.e. there is no service between Kenya and Uganda. As such, this segment is marked in yellow.

The once-proud Ugandan railway network today lies largely abandoned, a victim of Uganda's tragic history of dictatorship, bloodshed and economic disaster since the 1970s. The only inter-city line that maintains regular passenger service, is the main line from the capital, Kampala, to Tororo. As this line terminates at Kampala, on the shores of Lake Victoria (like the Kenyan line to Kisumu), it is of little interest to us.

From Tororo, Uganda's northern railway line stretches north and then west across the country in a grand arc, before terminating at Pakwach, the point where the Albert Nile river begins, adjacent to Lake Albert. (This line supposedly once continued from Pakwach to Arua; however, I haven't been able to find this extension marked on any maps, nor visible in any satellite imagery). The northernmost point of this railway line is at Gulu; and so, it is the segment of the line up to Gulu that interests us.

Sadly, the entire segment from Tororo to Gulu appears to be abandoned; whether there is even freight service today seems doubtful; thus, this segment is marked in yellow. And, doubly sad, Gulu is also the point at which a continuous, uninterrupted rail network all the way from Cape Town, comes to its present-day end. No rail line was ever constructed north of Gulu in Uganda. Therefore, it is at Gulu that the East African portion of the Cape to Cairo Railway bids us farewell.

Northern section

The northern section of the railway is mainly within Sudan and Egypt – although we'll be tracking (the missing section of) the route from northern Uganda; and, since 2011, the route also passes through the newly-independent South Sudan. As with its southern and eastern African counterparts, the northern part of the railway was primarily built by the British, during their former colonial rule in the region.

We pick up from where we finished in the previous section: Gulu in northern Uganda. As has already been mentioned: from Gulu, we hit the first (of only two) – and the most significant – of the missing links in the Cape to Cairo Railway. The next point where the railway begins again, is the city of Wau, located in north-western South Sudan. Therefore, this segment of the route is marked in red on the map. In the interests of at least marking some form of transport along the missing link, the red line follows the main highway route through the region: the Ugandan A104 highway from Gulu north to the border; and from there, at the city of Nimule (just over the border in South Sudan), the South Sudanese A43 highway to Juba (the capital), and then on to Wau (this highway route is about 1,000km in total).

There has been no shortage of discussion, both past and present, regarding plans to bridge this important gap in the rail network. There have even been recent official announcements by the governments of Uganda and of South Sudan, declaring their intention to build a new rail segment from Gulu to Wau. However, there hasn't been any concrete action since the present-day railheads were established about 50 years ago; and, considering that northern Uganda / South Sudan is one of the most troubled regions in the world today, I wouldn't hold my breath waiting for any fresh steel to appear on the ground (not to mention waiting for repairs of the existing neglected / war-damaged train lines). The folks over there have plenty of other, more urgent matters to attend to.

Wau is the southern terminus of the Sudanese rail network. From Wau, the line heads more-or-less straight up, crossing the border from South Sudan into Sudan, and joining the Khartoum – Darfur line at Babanusa. The Babanusa – Wau line was one of the last train lines to be completed in Sudan, opening in 1962 (around the same time as the Tororo – Gulu – Pakwach line opened in neighbouring Uganda). I found a colourful account of a passenger journey along this line, from around 2000. As I understand it, shortly after this time, the line was damaged by mines and explosives, a victim of the civil war. The line is supposedly rehabilitated, and passenger service has ostensibly resumed – however, personally I'm not convinced that this is the case. Therefore, this segment is marked in yellow on the map.

Similarly, the remaining segment of rail onwards to the capital – Babanusa to Khartoum – was apparently damaged during the civil war (that's on top of the line's ageing and dismally-maintained state). There are supposedly efforts underway to rehabilitate this line (along with the rest of the Sudanese rail network in general), and to restore regular services along it. I haven't been able to confirm whether passenger services have yet been restored; therefore, this segment is also marked in yellow on the map.

From the Sudanese capital Khartoum, the country's principal train line traverses the rest of the route north, running along the banks of the Upper Nile for about half the route, before making a beeline across the harsh expanse of the Nubian Desert, and terminating just before the Egyptian border at the town of Wadi Halfa, on the shores of Lake Nasser (the Sudanese side of which is called Lake Nubia). Although trains do appear to get suspended for long-ish intervals, this is the best-maintained route in war-ravaged Sudan, and it appears that regular passenger services are operating from Khartoum to Wadi Halfa. Therefore, this segment is marked in green on the map.

The border crossing from Sudan into Egypt is the second of the two missing links in the Cape to Cairo Railway. In fact, there isn't even a road connecting the two nations, at least not anywhere near the Nile / Lake Nasser. However, this missing link is of less concern, because: (a) the distance is much less (approximately 350km); and (b) Lake Nasser is a large and easily navigable body of water, with regular ferry services connecting Wadi Halfa in Sudan with Aswan in Egypt. Indeed, the convenience and the efficiency of the ferry service (along with the cargo services operating on the lake) is the very reason why nobody's ever bothered to build a rail link through this segment. So, this segment is marked in red on the map: the red line more-or-less follows the ferry route over the lake.

Aswan is Egypt's southernmost city; this has been the case for millenia, since it was the southern frontier of the realm of the Pharoahs, stretching back to ancient times. Aswan is also the southern terminus of the Egyptian rail network's main line; from here, the line snakes its way north, tracing the curves of the heavily-populated Nile River valley, all the way to Cairo, after which the vast Nile Delta begins.

Image source: About.com: Cruises.

The Aswan – Cairo line – the very last segment of Rhodes's grand envisioned network – is second only to the network's very first segment (Cape Town – Johannesburg) in terms of service offerings. There are a range of passenger services available, ranging from basic economy trains, to luxury tourist-oriented sleeper coaches, traversing the route daily. Although Egypt is currently in the midst of quite dramatic political turmoil (indeed, Egypt's recent military coup and ongoing protests are front-page news as I write this), as far as I know these issues haven't seriously disrupted the nation's train services. Therefore, this segment is marked in green on the map.

I should also note that after Cairo, Egypt's main rail line continues on to Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast. However, of course, the Cairo – Alexandria segment is not marked on the map, because it's a map of the Cape to Cairo railway, not the Cape to Alexandria railway! Also, Cairo could be considered to be "virtually" on the Mediterranean coast anyway, as it's connected by various offshoots of the Nile (in the Nile Delta) to the Mediterranean, with regular maritime traffic along these waterways.

End of the line

Well, there you have it: a thorough exercise in mapping and in narrating the present-day path of the Cape to Cairo Railway.

Personally, I've never been to Africa, let alone travelled any part of this long and diverse route. I'd love to do so, one day: although as I've described above, many parts of the route are currently quite a challenge to travel through, and will probably remain so for the foreseeable future. Naturally, I'd be delighted if anyone who has travelled any part of the route could share their "war stories" as comments here.

One question that I've asked myself many times, while researching and writing this article, is: in what year was the Cape to Cairo Railway at its best? (I.e. in what year was more of the line "green" than in any other year?). It would seem that the answer is probably 1976. This year was certainly not without its problems; but, at least as far as the Cape to Cairo endeavour goes, I believe that it was "as good as it's ever been".

This was the year that the TAZARA opened (which is to this day the "latest piece in the puzzle"), providing its inaugural Zambia – Tanzania service. It was one year before the 1977 dissolution of the East African Railways and Harbours Corporation, which jointly developed and managed the railways of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania (EAR&H's peak was probably in 1962, it was already in serious decline by 1976, but nevertheless it continued to provide comprehensive services until its end). And it was a year when Sudan's railways were in better operating condition, that nation being significantly less war-damaged than it is today (although Sudan had already suffered several years of civil war by then).

Unfortunately, it was also a year in which the Rhodesian Bush War was raging intensely – as such, on account of the hostilities between then-Rhodesia and Zambia, the Victoria Falls Bridge was largely closed to all traffic at that time (and, indeed, all travel within then-Rhodesia was probably quite difficult at that time). Then again, this hostility was also the main impetus for the construction of the TAZARA link; so, in the long-term, the tensions in then-Rhodesia actually improved the rail network more than they hampered it.

Additionally, it was a year in which Idi Amin's brutal reign of terror in Uganda was at its height. At that time, travel within Uganda was extremely dangerous, and infrastructure was being destroyed more commonly than it was being maintained.

I'm not the first person to make the observation – a fairly obvious one, after studying the route and its history – that travelling from Cape Town to Cairo overland (by train and/or by other transportation) never has been, and to this day is not, an easy expedition! There are numerous change-overs required, including change of railway guage, change to land vehicle, change to maritime vehicle, and more. The majority of the rail (and other) services along the route are poorly-maintained, prone to breakdowns, almost guaranteed to suffer extensive delays / cancellations, and vulnerable to seasonal weather fluctuations. And – as if all those "regular" hurdles weren't enough – many (perhaps the majority) of the regions through which the route passes are currently, or have in recent history been, unstable and dangerous trouble zones.

Hope you enjoyed my run-down (or should I say run-up?) of the Cape to Cairo Railway. Note that – as well as the KML files, which can be opened in Google Earth for best viewing of the route – the route is available here as a Google map.

Your contribution to the information presented here would be most welcome. If you have experience with path editing / Google Earth / KML (added bonus if you're Git / GitHub savvy, and know how to send pull requests), check out the route KML on GitHub, and feel free to refine it. Otherwise, feel free to post your route corrections, your African railway anecdotes, and all your most scathing criticism, using the comment form below (or contact me directly).