Where there be no roads

And now for something completely different, here's an interesting question. What terra firma places in the world are completely without roads? Where in the world will you find large areas, in which there are absolutely no official vehicle routes?

Image source: Favourite picture: Road construction in Siberia – RoadStars.

Naturally, such places also happen to be largely bereft of any other human infrastructure, such as buildings; and to be largely bereft of any human population. These are places where, in general, nothing at all is to be encountered save for sand, ice, and rock. However, that's just coincidental. My only criteria, for the purpose of this article, is a lack of roads.

Alaska

I was inspired to write this article after reading James Michener's epic novel Alaska. Before reading that book, I had only a vague knowledge of most things about Alaska, including just how big, how empty, and how inaccessible it is.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

One might think that, on account of it being part of the United States, Alaska boasts a reasonably comprehensive road network. Think again. Unlike the "Lower 48" (as the contiguous USA is referred to up there), only a small part of Alaska has roads of any sort at all, and that's the south-east corner around Anchorage and Fairbanks. And even there, the main routes are really part of the American Interstate network only on paper.

As you can see from the map, the entire western part of the state, and most of the north of the state, lack any road routes whatsoever. The north-east is also almost without roads, except for the Dalton Highway – better known locally as "The Haul Road" – which is a crude and uninhabited route for most of its length.

There has been discussion for decades about the possibility of building a road to Nome, which is the biggest settlement in western Alaska. However, such a road remains a pipe dream. It's also impossible to drive to Barrow, which is the biggest place in northern Alaska, and also the northernmost city in North America. This is despite Barrow being only about 300km west of the Dalton Highway's terminus at the Prudhoe Bay oilfields.

Road building is a trouble-fraught enterprise in Alaska, where distances are vast, population centres are few (or none), and geography / climate is harsh. In particular, building roads on permafrost (of which much of Alaska's terrain is) can be challenging, because the frozen soil expands in summer, and violently cracks whatever is on top of it. Also, while solid in winter, permafrost turns to muddy swamps in summer.

Image source: Yukon Animator.

It's no wonder, then, that for most of the far-flung outposts in northern and western Alaska, the main forms of transport are by sea or air. Where terrestrial transport is taken, it's most commonly in the form of a dog sled, and remains so to this day. In winter, Alaska's true main highways are its frozen rivers – particularly the mighty Yukon – which have been traversed by sled dogs, on foot (often with fatal results), and even by bicycle.

Canada

Much like its neighbour Alaska, northern Canada is also a vast expanse of frozen tundra that remains largely uninhabited. Considering the enormity of the area in question, Canada has actually made quite impressive progress in the building of roads further north. However, as the map illustrates, much of the north remains pristine and unblemished.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The biggest chunk of the roadless Canadian north is the territory of Nunavut. There are no roads to Nunavut (unless you count this), nor are there any linking its far-flung towns. As its Wikipedia page states, Nunavut is "the newest, largest, northernmost, and least populous territory of Canada". Nunavut's principal settlements of Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet, and Cambridge Bay can only be reached by sea or air.

Image source: Huffington Post.

The Northwest Territories is barren in many places, too. The entire eastern pocket of the Territories, bordering Nunavut and Saskatchewan (i.e. everything east of Tibbitt Lake, where the Ingraham Trail ends), has not a single road. And there are no roads north of Wrigley (where the Mackenzie Highway ends), except for the northernmost section of the Dempster Highway up to Inuvik. There are also no roads north of the Dempster Highway in Yukon Territory. And, on the other side of Canada, there are no roads in Quebec or Labrador north of Caniapiscau and the Trans-Taiga Road.

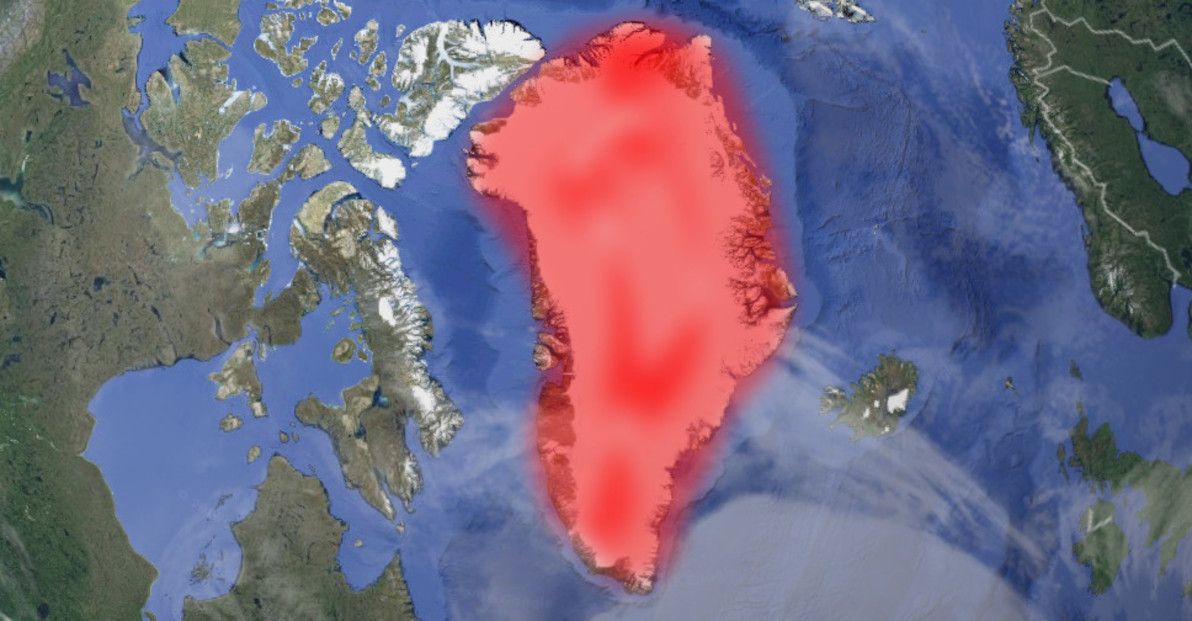

Greenland

Continuing east around the Arctic Circle, we come to Greenland, which is the largest contiguous and permanently-inhabited land mass in the world to have no roads at all between its settlements. Greenland is also the world's largest island.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The reason for the lack of road connections is the Greenland ice sheet, the second-largest body of ice in the world (after the Antarctic ice sheet), which covers 81% of the territory's surface. (And, as such, the answer to the age-old question "Is Greenland really green?", is overall "No!"). The only way to travel between Greenland's towns year-round is by air, with sea travel being possible only in summer, and dog sledding only in winter.

Svalbard

I'm generally avoiding covering small islands in this article, and am instead focusing on large continental areas. However, Svalbard (with Spitsbergen actually being the main island) is the largest island in the world – apart from islands that fall within other areas covered in this article – that has no roads between any of its settlements.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Svalbard is a Norwegian territory situated well north of the Arctic Circle. Its capital, Longyearbyen, is the northernmost city in the world. There are no roads linking Svalbard's handful of towns. Travel options involve air, sea, or snow.

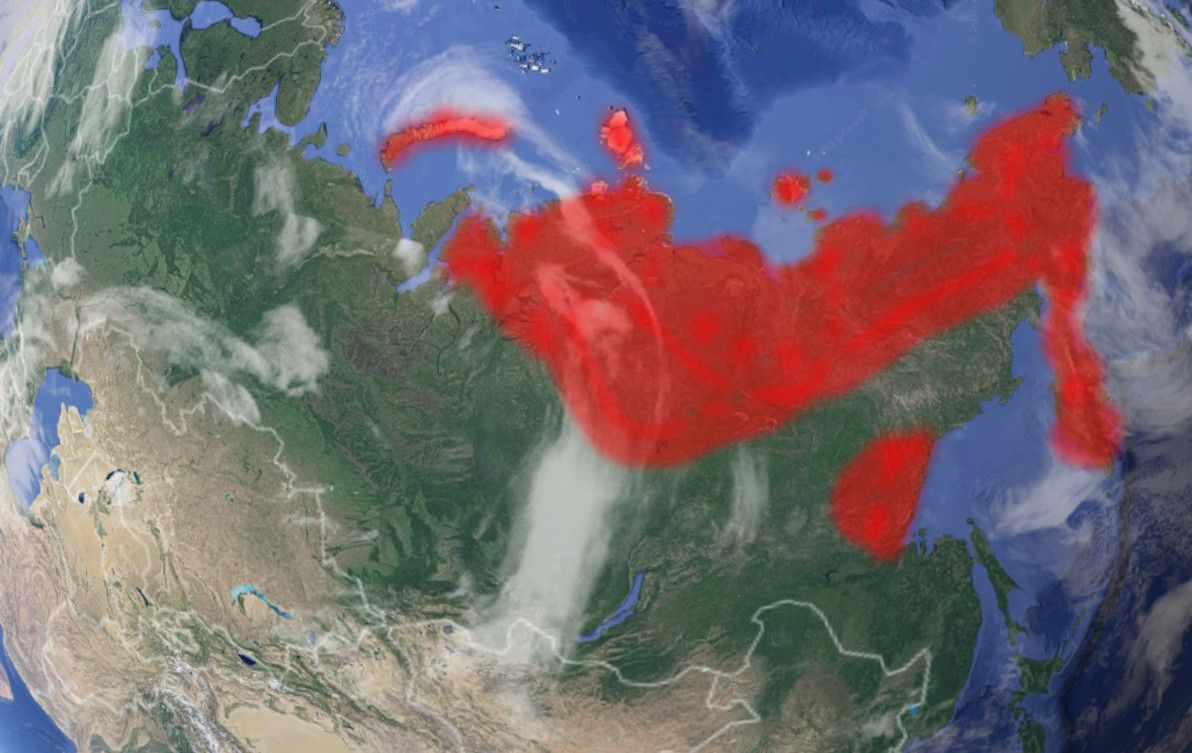

Siberia

The largest geographical region of the world's largest country (Russia), and well known as a vast "frozen wasteland", it should come as no surprise that Siberia features in this article. Siberia is the last of the arctic areas that I'll be covering here (indeed, if you continue east, you'll get back to Alaska, where I started). Consisting primarily of vast tracts of taiga and tundra, Siberia – particularly further north and further east – is a sparsely inhabited land of extreme cold and remoteness.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Considering the size, the emptiness, and the often challenging terrain, Russia has actually made quite impressive achievements in building transport routes through Siberia. Starting with the late days of the Russian Empire, going strong throughout much of the Soviet Era, and continuing with the present-day Russian Federation, civilisation has slowly but surely made inroads (no pun intended) into the region.

North-west Russia – which actually isn't part of Siberia, being west of the Ural Mountains – is quite well-serviced by roads these days. There are two modern roads going north all the way to the Barents Sea: the R21 Highway to Murmansk, and the M8 route to Arkhangelsk. Further east, closer to the start of Siberia proper, there's a road up to Vorkuta, but it's apparently quite crude.

Crossing the Urals east into Siberia proper, Yamalo-Nenets has until fairly recently been quite lacking in land routes, particularly north of the capital Salekhard. However, that has changed dramatically of late in the remote (and sparsely inhabited) Yamal Peninsula, where there is still no proper road, but where the brand-new Obskaya-Bovanenkovo Railroad is operating. Purpose-built for the exploitation of what is believed to be the world's largest natural gas field, this is now the northernmost railway line in the world (and it's due to be extended even further north). Further up from Yamalo-Nenets, the islands of Novaya Zemlya are without land routes.

Image source: The Washington Post.

East of the Yamal Peninsula, the great roadless expanse of northern Siberia begins. In Krasnoyarsk Krai, the second-biggest geographical division in Russia, there are no real roads past the area more than a few hundred km's north of the city of Krasnoyarsk. Nothing, that is, except for the road and railway (until recently the world's northernmost) that reach the northern outpost of Norilsk; although neither road nor rail are properly connected to the rest of Russia.

The Sakha Republic, Russia's biggest geographical division, is completely roadless save for the main highway passing through its south-east corner, and its capital, Yakutsk. In the far north of Sakha, on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, the town of Tiksi is reckoned to be the most remote settlement in all of Russia. Here in the depths of Siberia, the main transport is via the region's mighty rivers, of which the Lena forms the backbone of Sakha. In winter, dog sleds and ice vehicles are the norm.

In the extreme north-east of Siberia, where Chukotka and the Kamchatka Peninsula can be found, there are no road routes whatsoever. Transport in these areas is solely by sea, air, or ice. The only road that comes close to these areas is the Kolyma Highway, also infamously known as the Road of Bones; this route has been improved in recent years, although it's still hair-raising for much of its length, and it's still one of the most remote highways in the world. There are also no roads to Okhotsk (which was the first and the only Russian settlement on the Pacific coast for many centuries), nor to anywhere else in northern Khabarovsk Krai.

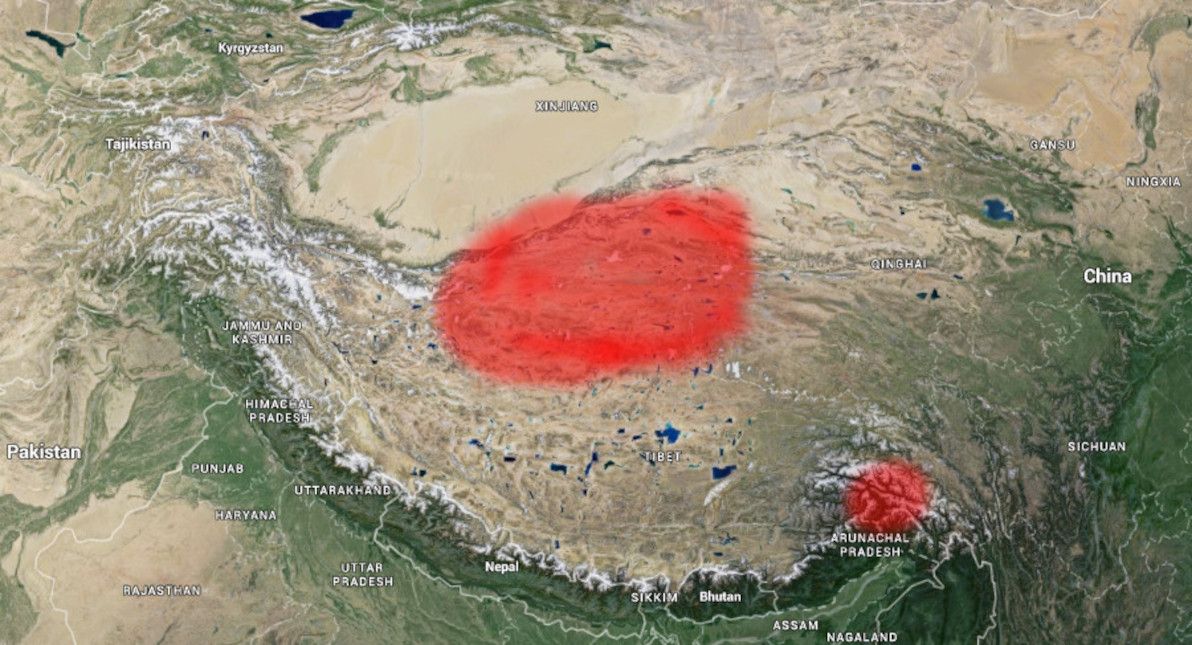

Tibet

A part of the People's Republic of China (whether they like it or not) since 1951, Tibet has come a long way since the old days, when the entire kingdom did not have a single road. Today, China claims that 70% of all villages in Tibet are connected by road. And things have also stepped up quite a big notch, since the 2006 opening of the Trans-Tibetan Railway, which is a marvel of modern engineering, and is (at over 5,000m in one section) the new highest-altitude railway in the world.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Virtually the entire southern half of Tibet boasts a road network today. However, the central north area of the region – as well as a fair bit of adjacent terrain in neighbouring Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces – still appears to be without roads. This area also looks like it's devoid of any significant settlements, with nothing much around except high-altitude tundra.

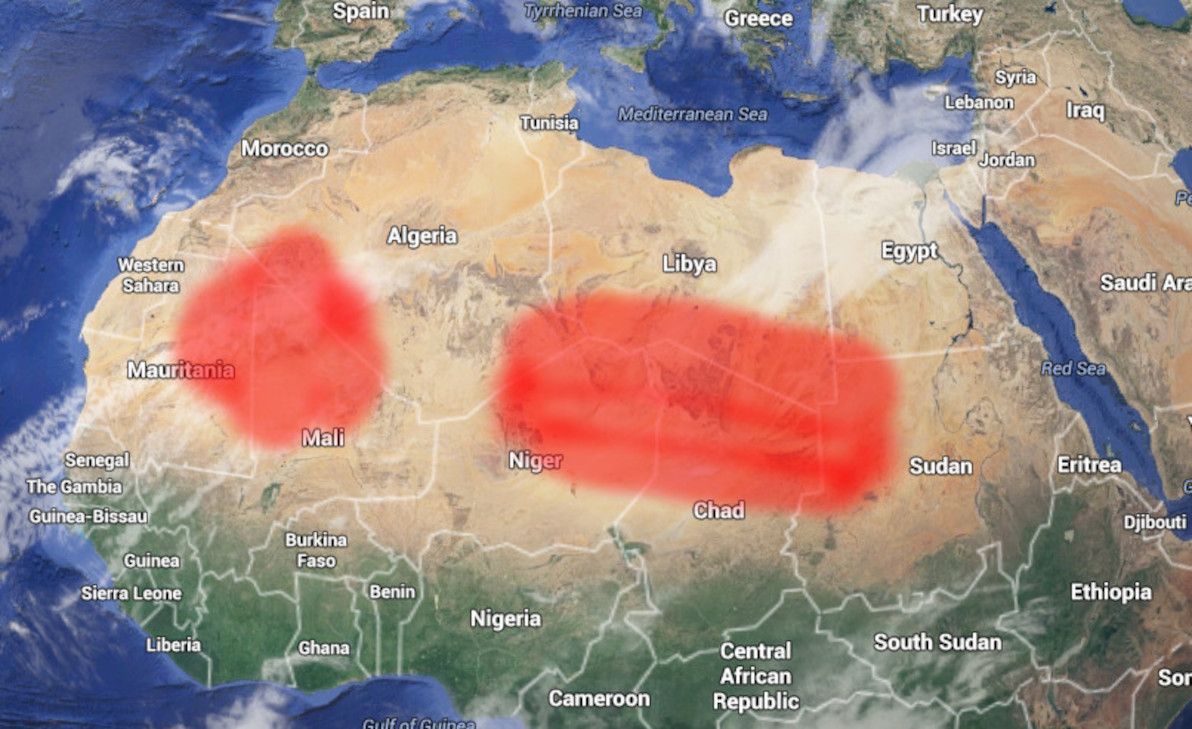

Sahara

Leaving the (mostly icy) roadless realms of North America and Eurasia behind us, it's time to turn our attention southward, where the regions in question are more of a mixed bag. First up: the Sahara, the world's largest desert, which covers almost all of northern Africa, and which is virtually uninhabited save for its semi-arid fringes.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

As the map shows, most of the parched interior of the Sahara is without roads. This includes: north-eastern Mauritania, northern Mali, south-eastern and south-western Algeria, northern Niger, southern Libya, northern Chad, north-west Sudan, and south-west Egypt. For all of the above, the only access is by air, by well-equipped 4WD convoy, or by camel caravan.

The only proper road cutting through this whole area, is the optimistically named Trans-Sahara Highway, the key part of which is the crossing from Agadez, Niger, north to Tamanrasset, Algeria. However, although most of the overall route (going all the way from Nigeria to Algeria) is paved, the section north of Agadez is still largely just a rough track through the sand, with occasional signposts indicating the way. There is also a rough track from Mali to Algeria (heading north from Kidal), but it appears to not be a proper road, even by Saharan standards.

Image source: Found the World.

I should also state (the obvious) here, namely that Saharan and Sub-Saharan Africa is not only one of the most arid and sparsely populated places on Earth, but that it's also one of the poorest, least developed, and most politically unstable places on Earth. As such, it should come as no surprise that overland travel through most of the roadless area is currently strongly discouraged, due to the security situation in many of the listed countries.

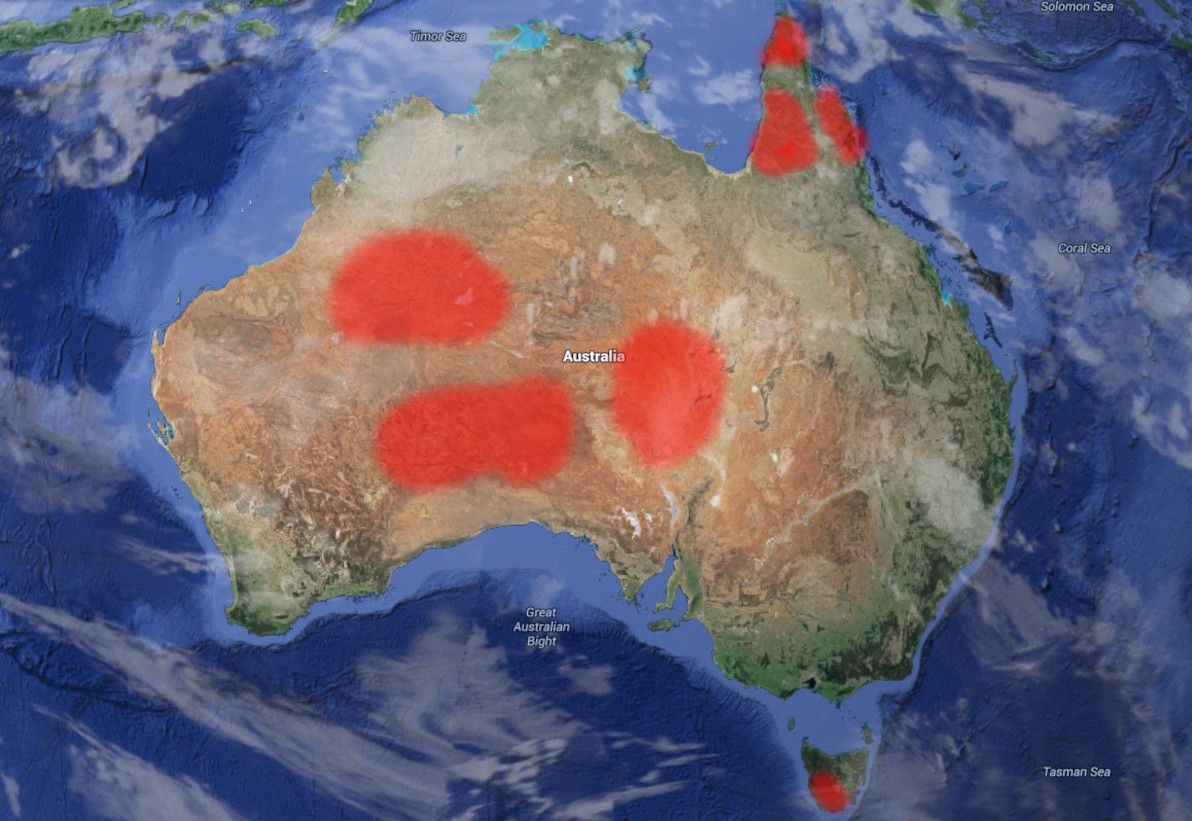

Australia

No run-down of the world's great roadless areas would be complete without including my sunburnt homeland, Australia. As I've blogged about before, there's a whole lot of nothing in the middle of this joint.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The biggest area of Australia to still lack road routes, is the heart of the Outback, in particular most of the east of Western Australia, and neighbouring land in the Northern Territory and South Australia. This area is bisected by only a single half-decent route (running east-west), the Outback Way – a route that is almost entirely unsealed – resulting in a north and a south chunk of roadless expanse.

The north chunk is centred on the Gibson Desert, and also includes large parts of the Great Sandy Desert and the Tanami Desert. The Gibson Desert, in particular, is considered to be the most remote place in Australia, and this is evidenced by its being where the last uncontacted Aboriginal tribe was discovered – those fellas didn't come outta the bush there 'til 1984. The south chunk consists of the Great Victoria Desert, which is the largest single desert in Australia, and which is similarly remote.

After that comes the area of Lake Eyre – Australia's biggest lake and, in typical Aussie style, one that seldom has any water in it – and the Simpson Desert to its north. The closest road to Lake Eyre itself is the Oodnadatta Track, and the only road that skirts the edge of the Simpson Desert is the Plenty Highway (which is actually part of the Outback Way mentioned above).

Image source: Avalook.

On the Apple Isle of Tasmania, the entire south-west region is an uninhabited, pristine, climatically extreme wilderness, and it's devoid of any roads at all. The only access is by sea or air: even 4WD is not an option in this hilly and forested area. Tasmania's famous South Coast Track bushwalk begins at the outpost of Melaleuca, where there is nothing except a small airstrip, and which can effectively only be reached by light aircraft. Not a trip for the faint-hearted.

Finally, in the extreme north-east of Australia, Cape York Peninsula remains one of the least accessible places on the continent, and has almost no roads (particularly the closer you get to the tip). The Peninsula Development Road, going as far north as Weipa, is the only proper road in the area: it's still largely unsealed, and like all other roads in the area, is closed and/or impassable for much of the year due to flooding. Up from there, Bamaga Road and the road to the tip are little more than rough tracks, and are only navigable by experienced 4WD'ers for a few months of the year. In this neck of the woods, you'll find that crocodiles, mosquitoes, jellyfish, and mud are much more common than roads.

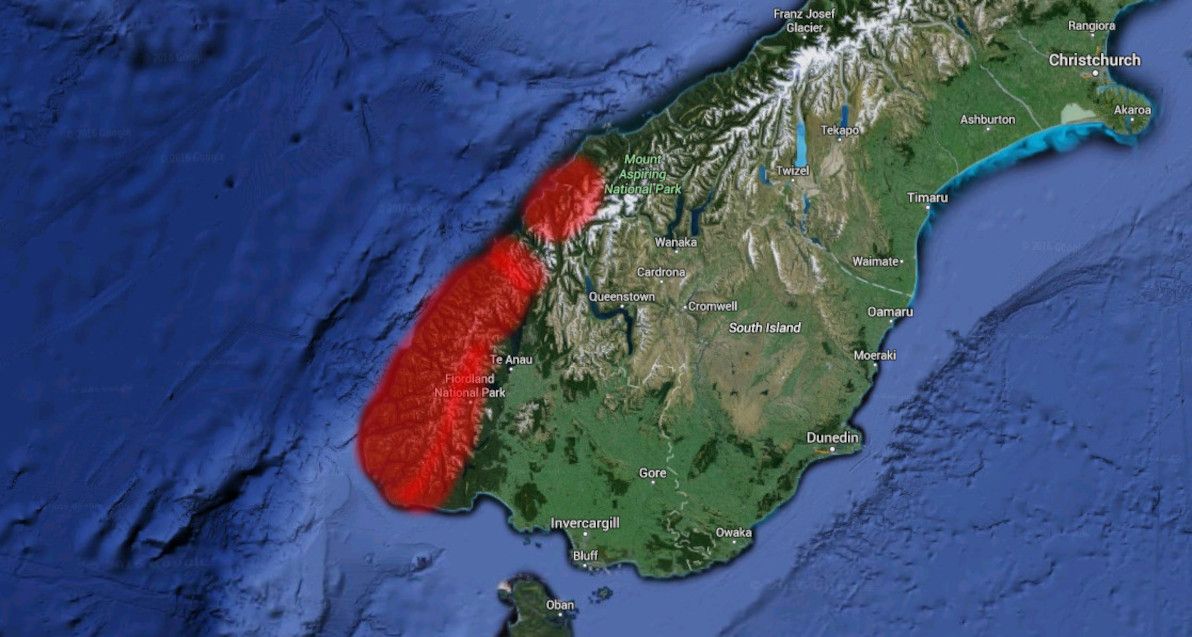

New Zealand

Heading east across the ditch, we come to the Land of the Long White Cloud. The South Island of New Zealand is well-known for its dazzling natural scenery: crystal-clear rivers, snow-capped mountains, jutting fjords, mammoth glaciers, and rolling hills. However, all that doesn't make for areas that are particularly easy to live in, or to construct roads through.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Essentially, the entire south-west edge of NZ's South Island is without road access. In particular, all of Fiordland National Park: the whole area south of Milford Sound, and east of Te Anau. Same deal for Mount Aspiring National Park, between Milford Sound and Jackson Bay. The only exception is Milford Sound itself, which can be accessed via the famous Homer Tunnel, an engineering feat that pierces the walls of Fiordland against all odds.

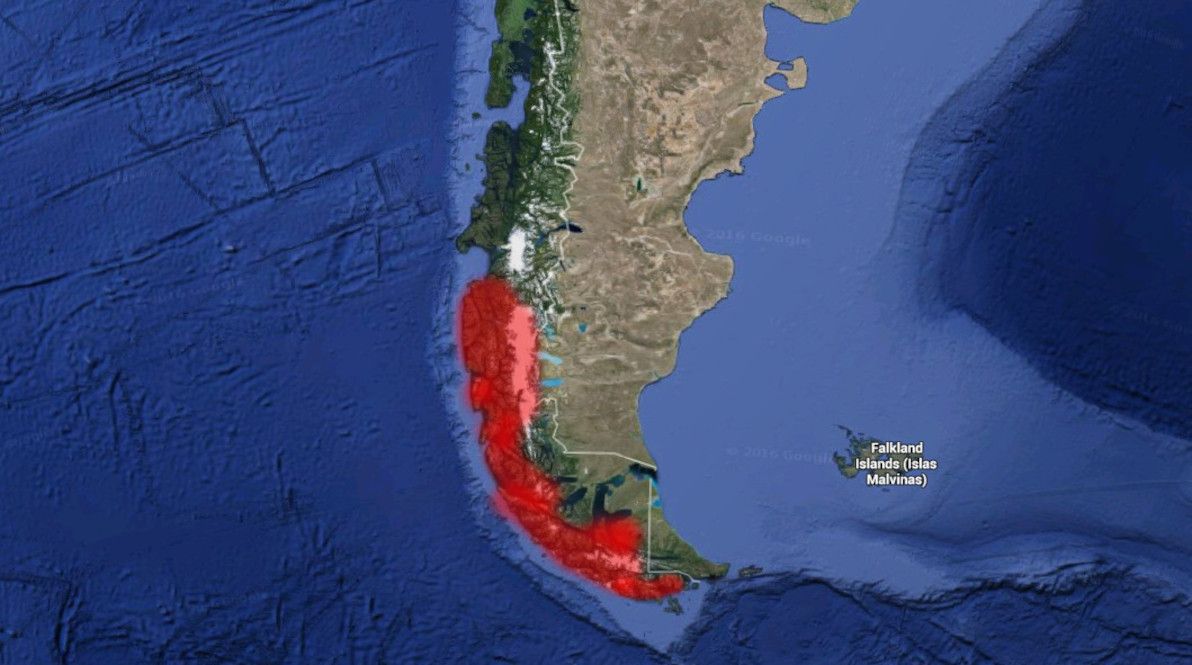

Chile

You'd think that, being such a long and thin country, getting at least one road to traverse the entire length of Chile wouldn't be so hard. Think again. Chile is the world's longest north-south country, and spans a wide range of climatic zones, from hot dry desert in the north, to glacial fjord-land in the extreme south. If you've seen Chile desde Arica hasta Punta Arenas (as I have!), then you've witnessed first-hand the geographical variety that it has to offer.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Roads can be found in all of Chile, except for one area: in the far south, between Villa O'Higgins and Torres del Paine. That is, the southern-most portion of Región de Aysén, and the northern half of Región de Magallanes, are entirely devoid of roads. This is mainly on account of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, one of the world's largest chunks of ice outside of the polar regions. This ice field was only traversed on foot, for the first time in history, as recently as 1998; it truly is one of our planet's final unconquered frontiers. No road will be crossing it anytime soon.

Image source: Mallin Colorado.

Much of the Chilean side of the island of Tierra del Fuego is also without roads: this includes most of Parque Karukinka, and all of Parque Nacional Alberto de Agostini.

The Chilean government has for many decades maintained the monumental effort of extending the Carretera Austral ever further south. The route reached its current terminus at Villa O'Higgins in 2000. The ultimate aim, of course, is to connect isolated Magallanes (which to this day can only be reached by road via Argentina) with the rest of the country. But considering all the ice, fjords, and extreme conditions in the way, it might be some time off yet.

Amazon

We now come to what is by far the most lush and life-filled place in this article: the Amazon Basin. Spanning several South American countries, the Amazon is home to the world's largest river (by water volume) and river system. Although there are some big settlements in the area (including Iquitos, the world's biggest city that's not accessible by road), in general there are more piranhas and anacondas than there are people in this jungle (the piranhas help to keep it that way!).

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Considering the challenges, quite a number of roads have actually been built in the Amazon in recent decades, particularly in the Brazilian part. The best-known of these is the Transamazônica, which – although rough and muddy as can be – has connected vast swaths of the jungle to civilisation. It should also be noted, that extensive road-building in this area is not necessarily a good thing: publicly-available satellite imagery clearly illustrates that, of the 20% of the Amazon that has been deforested to date, much of it has happened alongside roads.

The main parts of the Amazon that remain completely without roads are: western Estado do Amazonas and northern Estado do Pará in Brazil; most of north-eastern Peru (Departamento de Loreto); most of eastern Ecuador (the provinces in the Región amazónica del Ecuador); most of south-eastern Colombia (Amazonas, Vaupés, Guainía, Caquetá, and Guaviare departamentos); southern Venezuela (Estado de Amazonas); and the southern part of all the Guyanas (British Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana).

Image source: Getty Images.

The Amazon Basin probably already has more roads than it needs (or wants). In this part of the world, the rivers are the real highways – especially the Amazon itself, which has heavy marine traffic, despite being more than 5km wide in many parts (and that's in the dry season!). In fact, it's hard for terrestrial roads to compete with the rivers: for example, the BR-319 to Manaus has been virtually washed away by the jungle, and the main access to the Amazon's biggest city remains by boat.

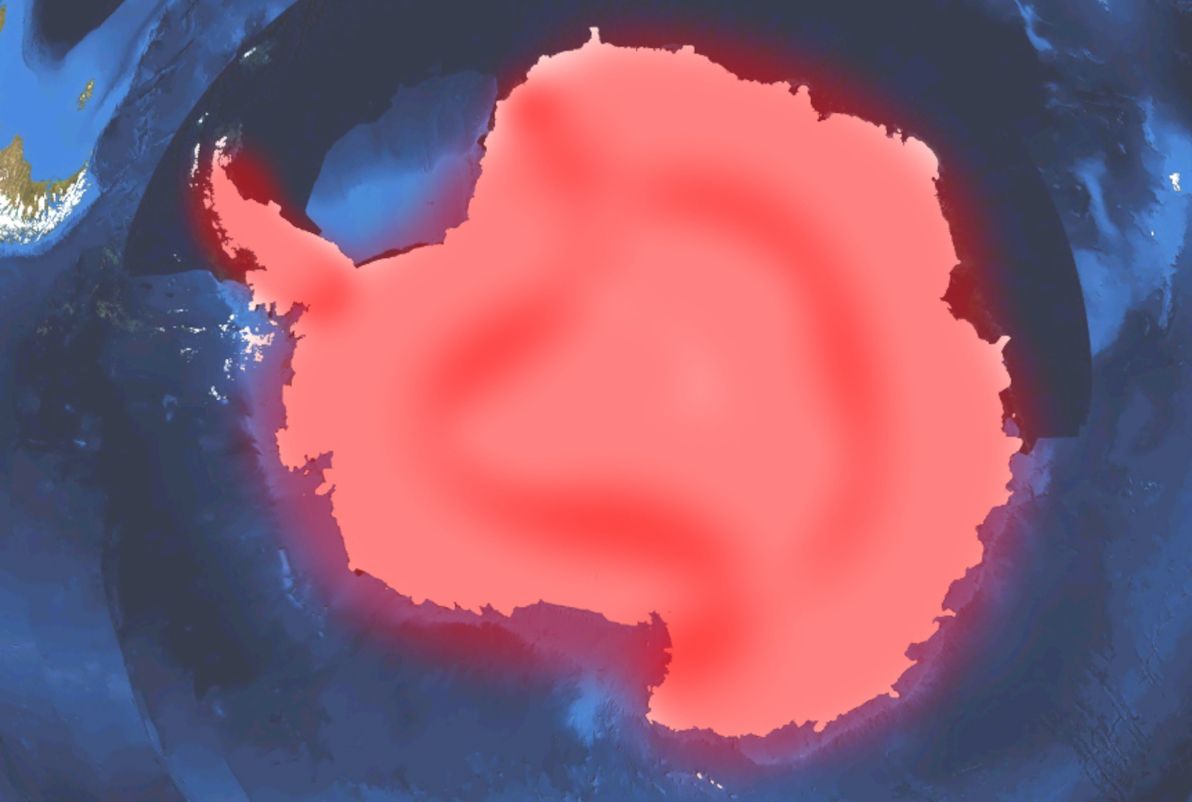

Antarctica

It's the world's fifth-largest continent. It's completely covered in ice. It has no permanent human population. It has no countries or (proper) territories. And it has no roads. And none of this should be a surprise to anyone!

Image source: Wikimedia Commons (red highlighting by yours truly).

As you might have guessed, not only are there no roads linking anywhere to anywhere else within Antarctica (except for ice trails), but (unlike every other area covered in this article) there aren't even any local roads within Antarctic settlements. The only regular access to Antarctica, and around Antarctica, is by air; even access by ship is difficult without helicopter support.

Where to?

There you have it: an overview of some of the most forlorn, desolate, but also beautiful places in the world, where the wonders of roads have never in all of human history been built. I've tried to cover as many relevant places as I can (and I've certainly covered more than I originally intended to), but of course I couldn't ever cover all of them. As I said, I've avoided discussion of islands, as a general rule, mainly because there is a colossal number of roadless islands around, and the list could go on forever.

I hope you've found this spin around the globe informative. And don't let such a minor inconvenience as a lack of roads stop you from visiting as many of these places as you can! Comments and feedback welcome.