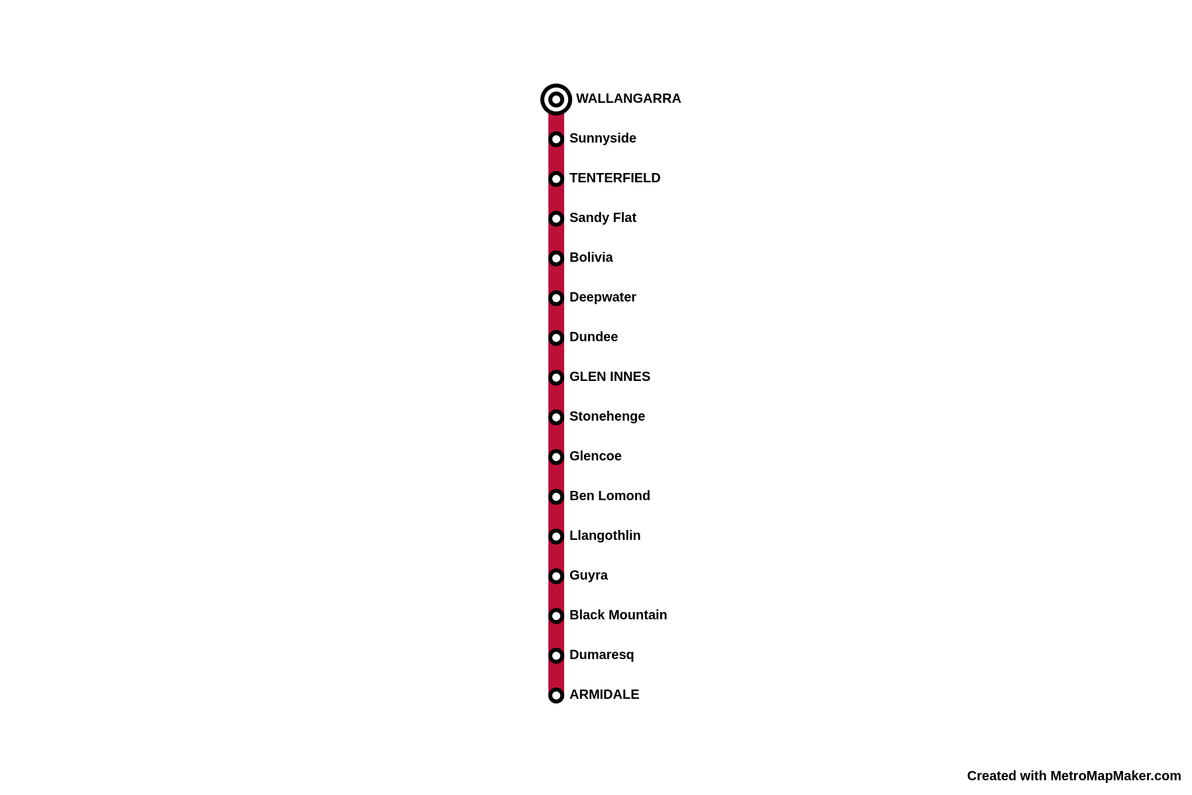

Thanks to: Metro Map Maker

Although I once drove through most of the Northern Tablelands, I wasn't aware of this railway, nor of its sad recent history, at the time. I just stumbled across it a few days ago, browsing maps online. I decided to pen this here wee thought, mainly because I was surprised at how scant information there is about the old line and its stations.

Image source: NSWrail.net

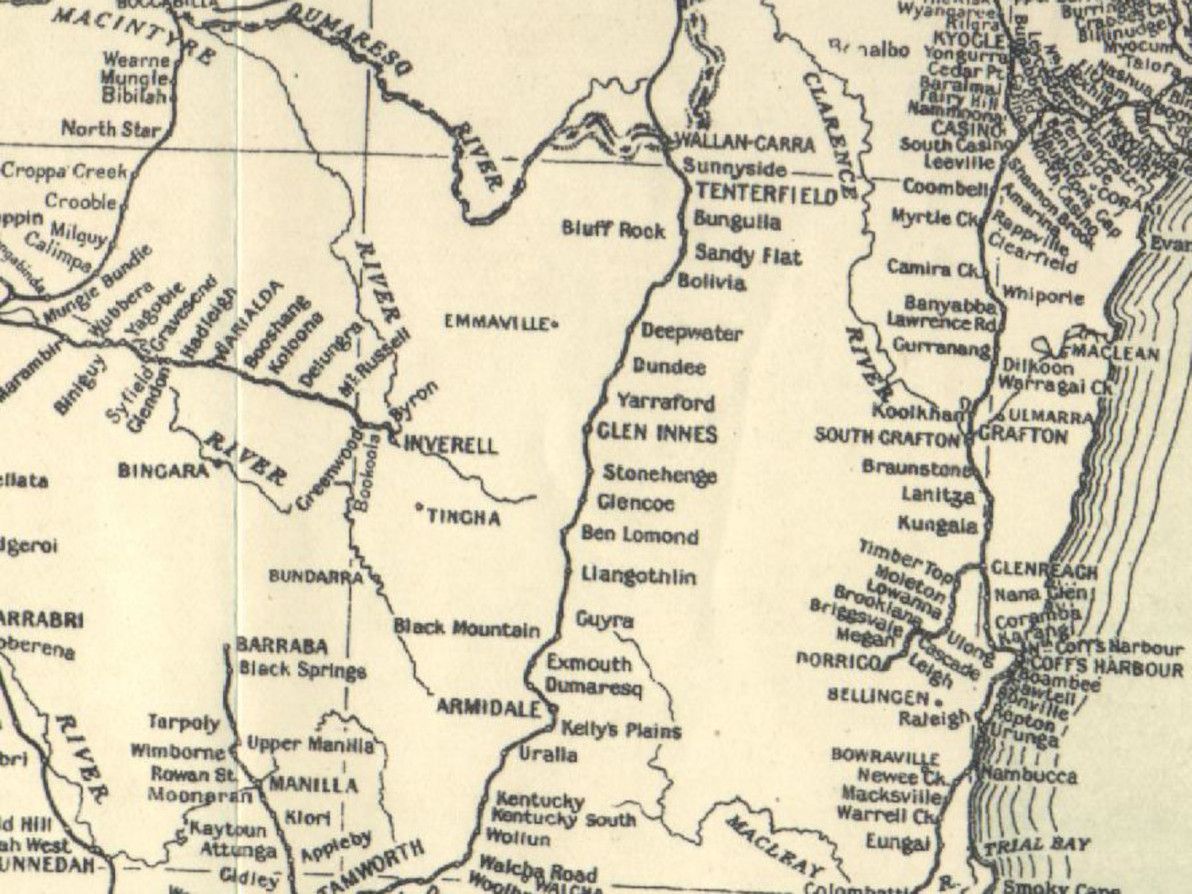

You may notice that some of the stops shown in the 1933 map, are missing from my metro map style illustration. I have omitted all of the stops that are listed as something other than "station" in this long list of facilities on the Main North Line. As far as I can tell, all of the stops listed as "unknown" or "loop", were at best very frugal platform sidings that barely qualified as stations, and their locations were never really populated towns (even going by the generous Aussie bush definition of "populated town", that is, "two people, three pubs").

Image source: NSWrail.net

Although some people haven't forgotten about it – particularly many of the locals – the railway is clearly disappearing from the collective consciousness, just as it's slowly but surely eroding and rotting away out there in the New England countryside.

Image source: NSWrail.net

Some of the stations along the old line were (apparently) once decent-sized towns, but it's not just the railway that's now long gone, it's the towns too! For example, Bolivia (the place that first caught my eye on the map, and that got me started researching all this – who would have imagined that there's a Bolivia in NSW?!), which legend has it was a bustling place at the turn of the 20th century, is nothing but a handful of derelict buildings now.

Image source: NSWrail.net

Other stations – and other towns, for that matter – along the old railway, appear to be faring better. In particular, Black Mountain station is being most admirably maintained by a local group, and Black Mountain village is also alive and well.

Image source: NSWrail.net

These days, on the NSW side, the Main North Line remains open up to Armidale, and a passenger train service continues to operate daily between Sydney and Armidale. On the Queensland side, the Southern line between Toowoomba and Wallangarra is officially still open to this day, and is maintained by Queensland Rail, however my understanding is that there's only a train actually on the tracks, all the way down to Wallangarra, once in a blue moon. On the Main line, a passenger service currently operates twice a week between Brisbane and Toowoomba (it's the Westlander service, which continues from Toowoomba all the way to Charleville).

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

The chances of the Armidale to Wallangarra railway ever re-opening are – to use the historically appropriate Aussie vernacular – Buckley's and none. The main idea that the local councils have been bandying about for the past few years, has been to convert the abandoned line into a rail trail for cycling. It looks like that plan is on the verge of going ahead, even though a number of local citizens are vehemently opposed to it. Personally, I don't think a rail trail is such a bad idea: the route will at least get more use, and will receive more maintenance, than it has for the past several decades; and it would bring a welcome trickle of tourists and adventurers to the region.

The Armidale to Wallangarra railway isn't completely lost nor forgotten. But it's a woeful echo of its long-gone glory days (it isn't even properly marked on Google Maps – although it's pretty well-marked on OpenStreetMap, and it's still quite visible on Google Maps satellite imagery). And, regretfully, it's one of countless many derelict train lines scattered across NSW: others include the Bombala line (which I've seen numerous times, running adjacent to the Monaro Highway, while driving down to Cooma from Sydney), the Nyngan to Bourke line, and the Murwillumbah line.

May this article, if nothing else, at least help to document what exactly the stations were on the old line, and how they're looking in this day and age. And, whether it's a rail trail or just an old relic by the time I get around to it, I'll have to head up there and see the old line for myself. I don't know exactly what future lies ahead for the Armidale to Wallangarra railway, but I sincerely hope that, both literally and figuratively, it doesn't simply fade into oblivion.

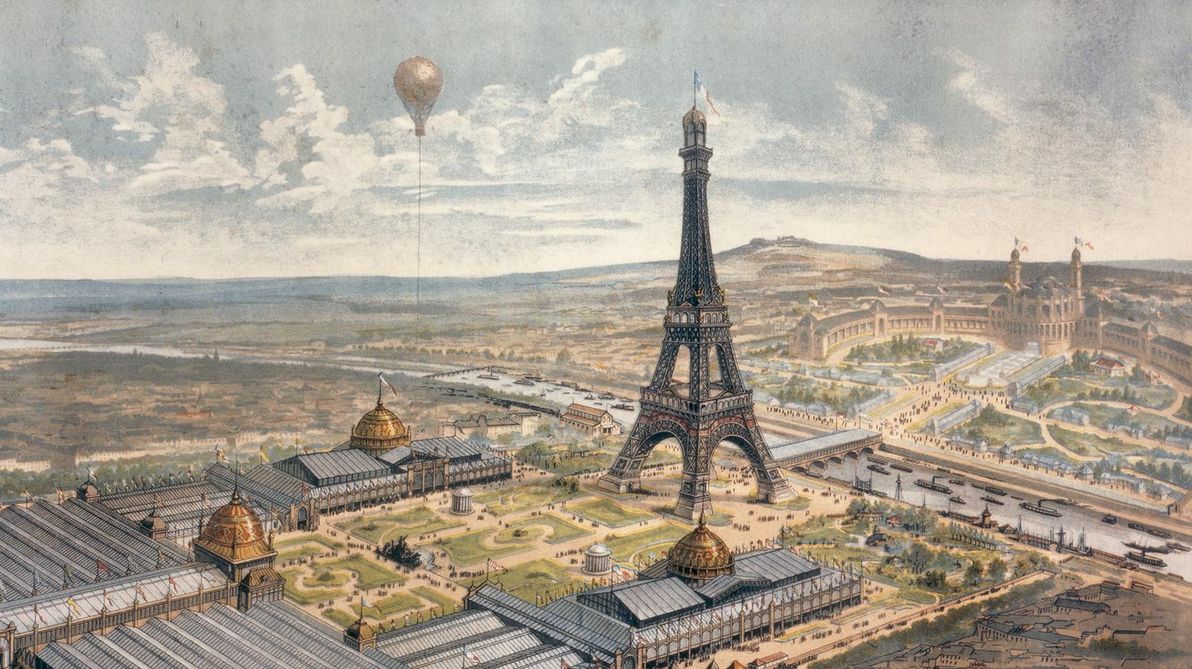

]]>From reading the wonderful epic novel Paris, by Edward Rutherford, I learned some facts about Gustave Eiffel's life, and about the Eiffel Tower's original conception, its construction, and its first few decades as the exclamation mark of the Paris skyline, that both surprised and intrigued me. Allow me to share these tidbits of history in this here humble article.

Image source: domain.com.au.

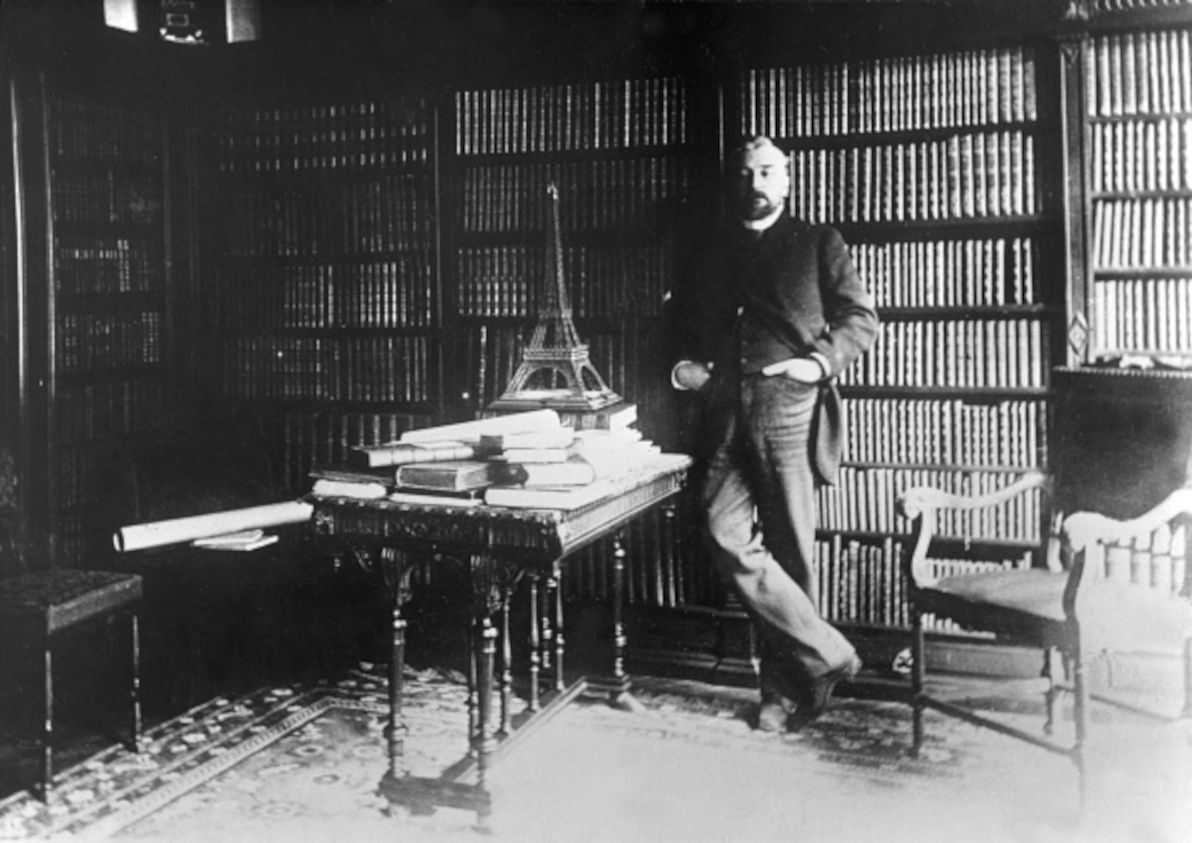

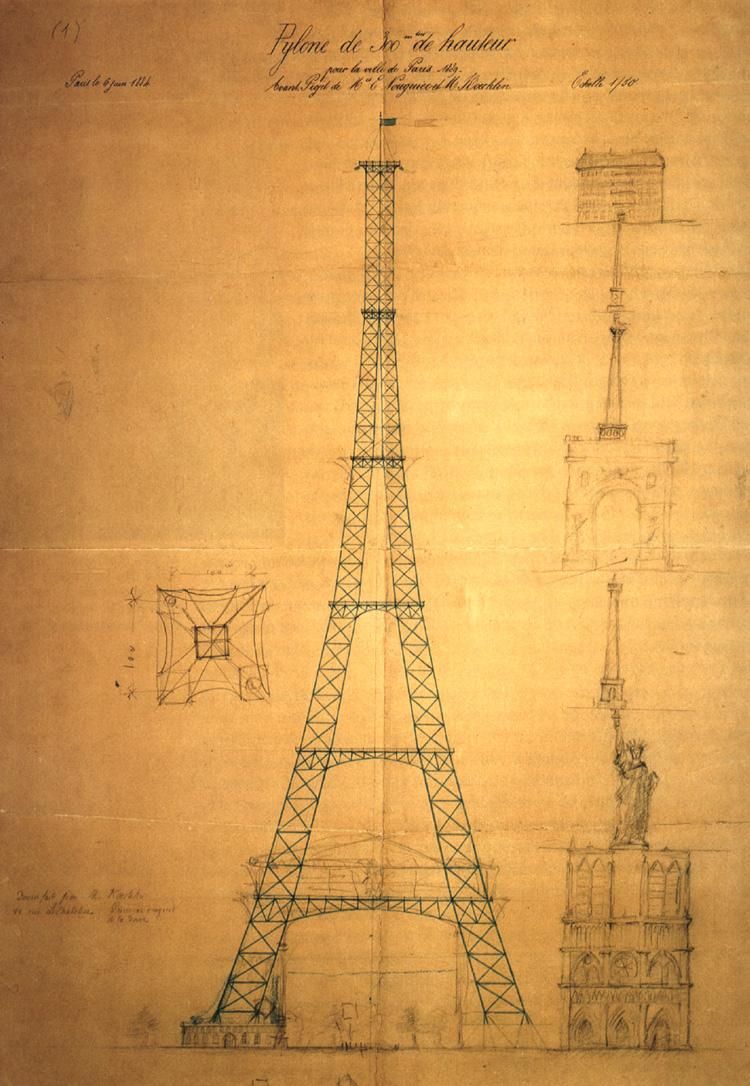

To begin with, the Eiffel Tower was not designed by Gustave Eiffel. The original idea and the first drafts of the design were produced by one Maurice Koechlin, who worked at Eiffel's firm. The same is true of Eiffel's other great claim to fame, the Statue of Liberty (which he built just before the Tower): after Eiffel's firm took over the project of building the statue, it was Koechlin who came up with Liberty's ingenious inner iron truss skeleton, and outer copper "skin", that makes her highly wind-resistant in the midst of blustery New York Harbour. It was a similar story for the Garabit Viaduct, and various other projects: although Eiffel himself was a highly capable engineer, it was Koechlin who was the mastermind, while Eiffel was the salesman and the celebrity.

Eiffel, and his colleagues Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, were engineers, not designers. In particular, they were renowned bridge-builders of their time. As such, their tower design was all about the practicalities of wind resistance, thermal expansion, and material strength; the Tower's aesthetic qualities were secondary considerations, with architect Stephen Sauvestre only being invited to contribute an artistic touch (such as the arches on the Tower's base), after the initial drafts were completed.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Eiffel Tower was built as the centrepiece of the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, after winning the 1886 competition that was held to find a suitable design. However, after choosing it, the City of Paris then put forward only a small modicum of the estimated money needed to build it, rather than the Tower's full estimated budget. As such, Eiffel agreed to cover the remainder of the construction costs out of his own pocket, but only on the condition that he receive all commercial income from the Tower, for 20 years from the date of its inauguration. This proved to be much to Eiffel's advantage in the long-term, as the Tower's income just during the Exposition Universelle itself – i.e. just during the first six months of its operating life – more than covered Eiffel's out-of-pocket costs; and the Tower has consistently operated at a profit ever since.

Image source: toureiffel.paris.

Pioneering construction projects of the 19th century (and, indeed, of all human history before then too) were, in general, hardly renowned for their occupational safety standards. I had always assumed that the building of the Eiffel Tower, which saw workmen reach more dizzying heights than ever before, had taken no small toll of lives. However, it just so happens that Gustave Eiffel was more than a mere engineer and a bourgeois, he was also a pioneer of safety: thanks to his insistence on the use of devices such as guard rails and movable stagings, the Eiffel Tower project amazingly saw only one fatality; and it wasn't even really a workplace accident, as the deceased, a workman named Angelo Scagliotti, climbed the tower while off duty, to impress his girlfriend, and sadly lost his footing.

The Tower's three levels, and its lifts and staircases, have always been accessible to the general public. However, something that not all visitors to the Tower may be aware of, is that near the summit of the Tower, just above the third level's viewing platform, sits what was originally Gustave Eiffel's private apartment. For the 20 years that he owned the rights to the Tower, Eiffel also enjoyed his own bachelor pad at the top! Eiffel reportedly received numerous requests to rent out the pad for a night, but he never did so, instead only inviting distinguished guests of his choosing, such as (no less than) Thomas Edison. The apartment is now open to the public as a museum. Still no word regarding when it will be listed on Airbnb; although another private apartment was more recently added lower down in the Tower and was rented out.

Image source: The Independent.

So why did Eiffel's contract for the rights to the Tower stipulate 20 years? Because the plan was, that after gracing the Paris cityscape for that many years, it was to be torn down! That's right, the Eiffel Tower – which today seems like such an invincible monument – was only ever meant to be a temporary structure. And what saved it? Was it that the City Government came to realise what a tremendous cash cow it could inherit? Was it that Parisians came to love and to admire what they had considered to be a detestable blight upon their elegant city? Not at all! The only thing that saved the Eiffel Tower was that, a few years prior to its scheduled doomsday, a little thing known as radio had been invented. The French military, who had started using the Tower as a radio antenna – realising that it was the best antenna in all of Paris, if not the world at that time – promptly declared the Tower vital to the defence of Paris, thus staving off the wrecking ball.

Image source: busy.org.

And the rest, as they say, is history. There are plenty more intriguing anecdotes about the Eiffel Tower, if you're interested in delving further. The Tower continued to have a colourful life, after the City of Paris relieved Eiffel of his rights to it in 1909, and after his death in 1923; and the story continues to this day. So, next time you have the good fortune of visiting La belle Paris, remember that there's much more to her tallest monument than just a fine view from the top.

]]>Communism – or, to be more precise, Marxism – made sweeping promises of a rosy utopian world society: all people are equal; from each according to his ability, to each according to his need; the end of the bourgeoisie, the rise of the proletariat; and the end of poverty. In reality, the nature of the communist societies that emerged during the 20th century was far from this grandiose vision.

Communism obviously was not successful in terms of the most obvious measure: namely, its own longevity. The world's first and its longest-lived communist regime, the Soviet Union, well and truly collapsed. The world's most populous country, the People's Republic of China, is stronger than ever, but effectively remains communist in name only (as does its southern neighbour, Vietnam).

However, this article does not seek to measure communism's success based on the survival rate of particular governments; nor does it seek to analyse (in any great detail) why particular regimes failed (and there's no shortage of other articles that do analyse just that). More important than whether the regimes themselves prospered or met their demise, is their legacy and their long-term impact on the societies that they presided over. So, how successful was the communism experiment, in actually improving the economic, political, and cultural conditions of the populations that experienced it?

Image source: FunnyJunk.

Success:

- Health care in Cuba (internationally recognised as being one of the world's best and most accessible public health care systems)

- The arts (Soviet theatre and Soviet ballet received funding and support for many years, as Cuban theatre still does; despite severely limiting artistic freedom, most communist regimes did actually make the arts thrive with subsidies)

- Education (despite the heavy dose of propaganda in schools, almost all communist regimes have massively improved their populations' literacy rates, and have invested heavily in more schools and universities, and in universal access to them)

- Infrastructure (for example, the USSR built an impressive railway network, a glorious metro in Moscow, and numerous power stations, although not all of amazing quality; and PR China has built an excellent highway network, among many other things)

- Womens' rights (the USSR strongly promoted women in the workforce, as does China and Cuba; the Soviet Union was also a pioneer in legalised abortion)

- Industrialisation (putting aside for a moment the enormous sacrifices made to achieve it, the fact is that the USSR, China, and Vietnam transformed rapidly from agrarian economies into industrial powerhouses under communism, and they remain world industrial heavyweights today)

Failure:

- Health care in general (Soviet health care was particularly infamous for its appalling state, and apparently not much has changed in Russia today; China's public health care system is generally considered adequate, but it's hardly an exemplary model either)

- Housing (for the vast majority, Soviet housing and Mao-era Chinese housing were of terrible quality, were overcrowded, and suffered from chronic shortages, and it continues to be this way in Cuba; although the Soviet residences can't be all bad, because Russians are now protesting their demolition)

- Environment (communist regimes, especially the USSR and PR China, have been directly responsible for some of the world's worst environmental catastrophes, the effects of which are expected to linger on for centuries)

- Food security (the communist practice of collectivisation of agriculture has almost always had disastrous results – the USSR experienced food shortages throughout its existence, Maoist China suffered one of the worst famines in human history, and North Korea has endured such acute food scarcity that its population has on occasion resorted to cannibalism)

- Freedom (all communist states so far in history have been totalitarian regimes, and have severely curtailed all freedoms – of speech, of movement, of artistic expression, of religion – and that oppressive legacy lives on to this day)

- Culture and heritage (communist regimes have waged war against their peoples' traditions, religions, and icons, and they have also physically destroyed numerous historic artifacts and monuments; this has resulted in cultural vacuums that may never fully heal)

- Propaganda (truth has invariably taken a back seat to propaganda in communist states – supposedly, the government is perfect, foreign powers are evil, and history can be re-written)

- Corruption (far from the Marxist ideal of universal equality, it has most definitely been a case of some are more equal than others in communist states – communism has engendered endemic bribery and nepotism every time)

- Morale (as the old communist joke goes: "we pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us" – nobody has any motivation to work hard, so productivity nationwide plummets; as well as work morale, the oppressive atmosphere of communist regimes has resulted in ongoing social malaise – modern Russia, for example, has one of the world's highest alcoholism and suicide rates)

- Human damage (rather than making everyone a winner, communism has generally made almost everyone a victim – as well as the huge number of people murdered, imprisoned, and tortured as enemies of a communist state, almost all citizens other than Party elites have endured prolonged suffering due to the states' constant intrusion into their lives)

Image source: FunnyJunk.

Closing remarks

Personally, I have always considered myself quite a "leftie": I'm a supporter of socially progressive causes, and in particular, I've always been involved with environmental movements. However, I've never considered myself a socialist or a communist, and I hope that this brief article on communism reflects what I believe are my fairly balanced and objective views on the topic.

Based on my list of pros and cons above, I would quite strongly tend to conclude that, overall, the communism experiment of the 20th century was not successful at improving the economic, political, and cultural conditions of the populations that experienced it.

I'm reluctant to draw comparisons, because I feel that it's a case of apples and oranges, and also because I feel that a pure analysis should judge communist regimes on their merits and faults, and on theirs alone. However, the fact is that, based on the items in my lists above, much more success has been achieved, and much less failure has occurred, in capitalist democracies, than has been the case in communist states (and the pinnacle has really been achieved in the world's socialist democracies). The Nordic Model – and indeed the model of my own home country, Australia – demonstrates that a high quality of life and a high level of equality are attainable without going down the path of Marxist Communism; indeed, arguably those things are attainable only if Marxist Communism is avoided.

I hope you appreciate what I have endeavoured to do in this article: that is, to avoid the question of whether or not communist theory is fundamentally flawed; to avoid a religious rant about the "evils" of communism or of capitalism; and to avoid judging communism based on its means, and to instead concentrate on what ends it achieved. And I humbly hope that I have stuck to that plan laudably. Because if one thing is needed more than anything else in the arena of analyses of communism, it's clear-sightedness, and a focus on the hard facts, rather than religious zeal and ideological ranting.

]]>Company rule, and the subsequent rule of the British Raj, are also acknowledged as contributing positively to the shaping of Modern India, having introduced the English language, built the railways, and established political and military unity. But these are overshadowed by its legacy of corporate greed and wholesale plunder, which continues to haunt the region to this day.

I recently read Four Heroes of India (1898), by F.M. Holmes, an antique book that paints a rose-coloured picture of Company (and later British Government) rule on the Subcontinent. To the modern reader, the book is so incredibly biased in favour of British colonialism that it would be hilarious, were it not so alarming. Holmes's four heroes were notable military and government figures of 18th and 19th century British India.

Image source: eBay.

I'd like to present here four alternative heroes: men (yes, sorry, still all men!) who in my opinion represented the British far more nobly, and who left a far more worthwhile legacy in India. All four of these figures were founders or early members of The Asiatic Society (of Bengal), and all were pioneering academics who contributed to linguistics, science, and literature in the context of South Asian studies.

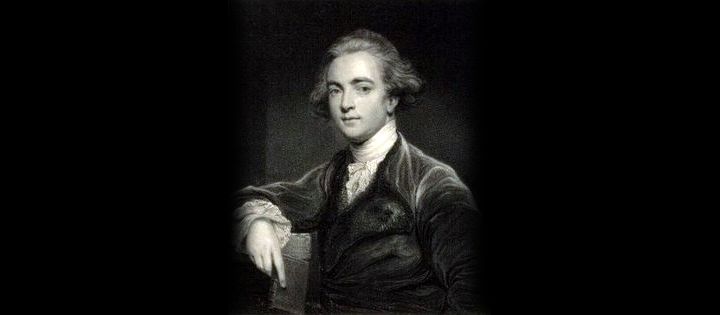

William Jones

The first of these four personalities was by far the most famous and influential. Sir William Jones was truly a giant of his era. The man was nothing short of a prodigy in the field of philology (which is arguably the pre-modern equivalent of linguistics). During his productive life, Jones is believed to have become proficient in no less than 28 languages, making him quite the polyglot:

Eight languages studied critically: English, Latin, French, Italian, Greek, Arabic, Persian, Sanscrit [sic]. Eight studied less perfectly, but all intelligible with a dictionary: Spanish, Portuguese, German, Runick [sic], Hebrew, Bengali, Hindi, Turkish. Twelve studied least perfectly, but all attainable: Tibetian [sic], Pâli [sic], Pahlavi, Deri …, Russian, Syriac, Ethiopic, Coptic, Welsh, Swedish, Dutch, Chinese. Twenty-eight languages.

Source: Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Correspondence, of Sir William Jones, John Shore Baron Teignmouth, 1806, Page 376.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Jones is most famous in scholarly history for being the person who first proposed the linguistic family of Indo-European languages, and thus for being one of the fathers of comparative linguistics. His work laid the foundations for the theory of a Proto-Indo-European mother tongue, which was researched in-depth by later linguists, and which is widely accepted to this day as being a language that existed and that had a sizeable native speaker population (despite there being no concrete evidence for it).

Jones spent 10 years in India, working in Calcutta as a judge. During this time, he founded The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Jones was the foremost of a loosely-connected group of British gentlemen who called themselves orientalists. (At that time, "oriental studies" referred primarily to India and Persia, rather than to China and her neighbours as it does today.)

Like his peers in the Society, Jones was a prolific translator. He produced the authoritative English translation of numerous important Sanskrit documents, including Manu Smriti (Laws of Manu), and Abhiknana Shakuntala. In the field of his "day job" (law), he established the right of Indian citizens to trial by jury under Indian jurisprudence. Plus, in his spare time, he studied Hindu astronomy, botany, and literature.

James Prinsep

The numismatist James Prinsep, who worked at the Benares (Varanasi) and Calcutta mints in India for nearly 20 years, was another of the notable British orientalists of the Company era. Although not quite in Jones's league, he was nevertheless an intelligent man who made valuable contributions to academia. His life was also unfortunately short: he died at the age of 40, after falling sick of an unknown illness and failing to recover.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Prinsep was the founding editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He is best remembered as the pioneer of numismatics (the study of coins) on the Indian Subcontinent: in particular, he studied numerous coins of ancient Bactrian and Kushan origin. Prinsep also worked on deciphering the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts; and he contributed to the science of meteorology.

Charles Wilkins

The typographer Sir Charles Wilkins arrived in India in 1770, several years before Jones and most of the other orientalists. He is considered the first British person in Company India to have mastered the Sanskrit language. Wilkins is best remembered as having created the world's first Bengali typeface, which became a necessity when he was charged with printing the important text A Grammar of the Bengal Language (the first book written in Bengali to ever be printed), written by fellow orientalist Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, and more-or-less commissioned by Governor Warren Hastings.

It should come as no surprise that this pioneering man was one of the founders of The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Like many of his colleagues, Wilkins left a proud legacy as a translator: he was the first person to translate into English the Bhagavad Gita, the most revered holy text in all of Hindu lore. He was also the first director of the "India Office Library".

H. H. Wilson

The doctor Horace Hayman Wilson was in India slightly later than the other gentlemen listed here, not having arrived in India (as a surgeon) until 1808. Wilson was, for a part of his time in Company India, honoured with the role of Secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Wilson was one of the key people to continue Jones's great endeavour of bridging the gap between English and Sanskrit. His key contribution was writing the world's first comprehensive Sanskrit-English dictionary. He also translated the Meghaduuta into English. In his capacity as a doctor, he researched and published on the matter of traditional Indian medical practices. He also advocated for the continued use of local languages (rather than of English) for instruction in Indian native schools.

The legacy

There you have it: my humble short-list of four men who represent the better side of the British presence in Company India. These men, and other orientalists like them, are by no means perfect, either. They too participated in the Company's exploitative regime. They too were part of the ruling elite. They were no Mother Teresa (the main thing they shared in common with her was geographical location). They did little to help the day-to-day lives of ordinary Indians living in poverty.

Nevertheless, they spent their time in India focused on what I believe were noble endeavours; at least, far nobler than the purely military and economic pursuits of many of their peers. Their official vocations were in administration and business enterprise, but they chose to devote themselves as much as possible to academia. Their contributions to the field of language, in particular – under that title I include philology, literature, and translation – were of long-lasting value not just to European gentlemen, but also to the educational foundations of modern India.

In recent times, the term orientalism has come to be synonymous with imperialism and racism (particularly in the context of the Middle East, not so much for South Asia). And it is argued that the orientalists of British India were primarily concerned with strengthening Company rule by extracting knowledge, rather than with truly embracing or respecting India's cultural richness. I would argue that, for the orientalists presented here at least, this was not the case: of course they were agents of British interests, but they also genuinely came to respect and admire what they studied in India, rather than being contemptuous of it.

The legacy of British orientalism in India was, in my opinion, one of the better legacies of British India in general. It's widely acknowledged that it had a positive long-term educational and intellectual effect on the Subcontinent. It's also a topic about which there seems to be insufficient material available – particularly regarding the biographical details of individual orientalists, apart from Jones – so I hope this article is useful to anyone seeking further sources.

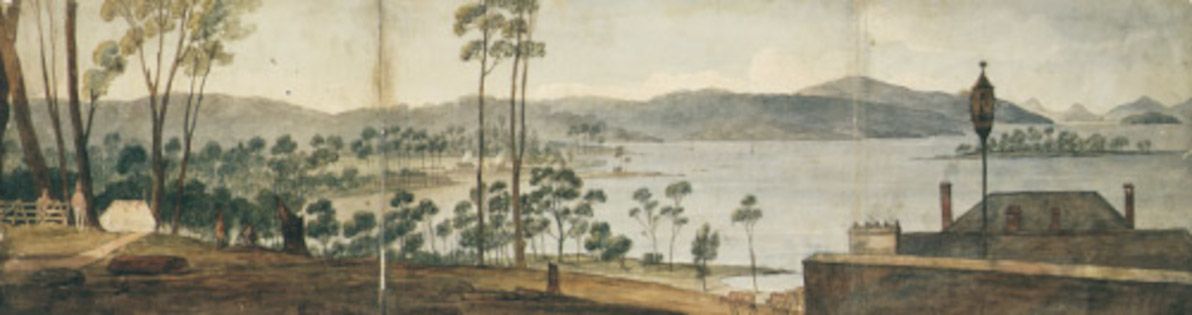

]]>I recently came across a gem of literary work, from the early days of New South Wales: The Present State of Australia, by Robert Dawson. The author spent several years (1826-1828) living in the Port Stephens area (about 200km north of Sydney), as chief agent of the Australian Agricultural Company, where he was tasked with establishing a grazing property. During his time there, Dawson lived side-by-side with the Worimi indigenous peoples, and Worimi anecdotes form a significant part of his book (which, officially, is focused on practical advice for British people considering migration to the Australian frontier).

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

In this article, I'd like to share quite a number of quotes from Dawson's book, which in my opinion may well constitute the oldest known (albeit informal) anthropological study of Indigenous Australians. Considering his rich account of Aboriginal tribal life, I find it surprising that Dawson seems to have been largely forgotten by the history books, and that The Present State of Australia has never been re-published since its first edition in 1830 (the copies produced in 1987 are just fascimiles of the original). I hope that this article serves as a tribute to someone who was an exemplary exception to what was then the norm.

Language

The book includes many passages containing Aboriginal words interspersed with English, as well as English words spelt phonetically (and amusingly) as the tribespeople pronounced them; contemporary Australians should find many of these examples familiar, from the modern-day Aboriginal accents:

Before I left Port Stephens, I intimated to them that I should soon return in a "corbon" (large) ship, with a "murry" (great) plenty of white people, and murry tousand things for them to eat … They promised to get me "murry tousand bark." "Oh! plenty bark, massa." "Plenty black pellow, massa: get plenty bark." "Tree, pour, pive nangry" (three, four, five days) make plenty bark for white pellow, massa." "You come back toon?" "We look out for corbon ship on corbon water," (the sea.) "We tee, (see,) massa." … they sent to inform me that they wished to have a corrobery (dance) if I would allow it.

(page 60)

On occasion, Dawson even goes into grammatical details of the indigenous languages:

"Bael me (I don't) care." The word bael means no, not, or any negative: they frequently say, "Bael we like it;" "Bael dat good;" "Bael me go dere."

(page 65)

It's clear that Dawson himself became quite prolific in the Worimi language, and that – at least for a while – an English-Worimi "creole" emerged as part of white-black dialogue in the Port Stephens area.

Food and water

Although this is probably one of the better-documented Aboriginal traits from the period, I'd also like to note Dawson's accounts of the tribespeoples' fondness for European food, especially for sugar:

They are exceedingly fond of biscuit, bread, or flour, which they knead and bake in the ashes … but the article of food which appears most delicious to them, is the boiled meal of Indian corn; and next to it the corn roasted in the ashes, like chestnuts: of sugar too they are inordinately fond, as well as of everything sweet. One of their greatest treats is to get an Indian bag that has had sugar in it: this they cut into pieces and boil in water. They drink this liquor till they sometimes become intoxicated, and till they are fairly blown out, like an ox in clover, and can take no more.

(page 59)

Dawson also described their manner of eating; his account is not exactly flattering, and he clearly considers this behaviour to be "savage":

The natives always eat (when allowed to do so) till they can go on no longer: they then usually fall asleep on the spot, leaving the remainder of the kangaroo before the fire, to keep it warm. Whenever they awake, which is generally three or four times during the night, they begin eating again; and as long as any food remains they will never stir from the place, unless forced to do so. I was obliged at last to put a stop, when I could, to this sort of gluttony, finding that it incapacitated them from exerting themselves as they were required to do the following day.

(page 123)

Regarding water, Dawson gave a practical description of the Worimi technique for getting a drink in the bush in dry times (and admits that said technique saved him from being up the creek a few times); now, of course, we know that similar techniques were common for virtually all Aboriginal peoples across Australia:

It sometimes happens, in dry seasons, that water is very scarce, particularly near the shores. In such cases, whenever they find a spring, they scratch a hole with their fingers, (the ground being always sandy near the sea,) and suck the water out of the pool through tufts or whisps of grass, in order to avoid dirt or insects. Often have I witnessed and joined in this, and as often felt indebted to them for their example.

They would walk miles rather than drink bad water. Indeed, they were such excellent judges of water, that I always depended upon their selection when we encamped at a distance from a river, and was never disappointed.

(page 150)

Tools and weapons

In numerous sections, Dawson described various tools that the Aborigines used, and their skill and dexterity in fashioning and maintaining them:

[The old man] scraped the point of his spear, which was at least about eight feet long, with a broken shell, and put it in the fire to harden. Having done this, he drew the spear over the blaze of the fire repeatedly, and then placed it between his teeth, in which position he applied both his hands to straighten it, examining it afterwards with one eye closed, as a carpenter would do his planed work. The dexterous and workmanlike manner in which he performed his task, interested me exceedingly; while the savage appearance and attitude of his body, as he sat on the ground before a blazing fire in the forest, with a black youth seated on either side of him, watching attentively his proceedings, formed as fine a picture of savage life as can be conceived.

(page 16)

To the modern reader such as myself, Dawson's use of language (e.g. "a picture of savage life") invariably gives off a whiff of contempt and "European superiority". Personally, I try to give him the benefit of the doubt, and to brush this off as simply "using the vernacular of the time". In my opinion, this is fair justification for Dawson's manner of writing to some extent; but it also shows that he wasn't completely innocent, either: he too held some of the very views which he criticised in his contemporaries.

The tribespeople also exercised great agility in gathering the raw materials for their tools and shelters:

Before a white man can strip the bark beyond his own height, he is obliged to cut down the tree; but a native can go up the smooth branchless stems of the tallest trees, to any height, by cutting notches in the surface large enough only to place the great toe in, upon which he supports himself, while he strips the bark quite round the tree, in lengths from three to six feet. These form temporary sides and coverings for huts of the best description.

(page 19)

And they were quite dexterous in their crafting of nets and other items:

They [the women] make string out of bark with astonishing facility, and as good as you can get in England, by twisting and rolling it in a curious manner with the palm of the hand on the thigh. With this they make nets … These nets are slung by a string round their forehead, and hang down their backs, and are used like a work-bag or reticule. They contain all the articles they carry about with them, such as fishing hooks made from oyster or pearl shells, broken shells, or pieces of glass, when they can get them, to scrape the spears to a thin and sharp point, with prepared bark for string, gum for gluing different parts of their war and fishing spears, and sometime oysters and fish when they move from the shore to the interior.

(page 67)

Music and dance

Dawson wrote fondly of his being witness to corroborees on several occasions, and he recorded valuable details of the song and dance involved:

A man with a woman or two act as musicians, by striking two sticks together, and singing or bawling a song, which I cannot well describe to you; it is chiefly in half tones, extending sometimes very high and loud, and then descending so low as almost to sink to nothing. The dance is exceedingly amusing, but the movement of the limbs is such as no European could perform: it is more like the limbs of a pasteboard harlequin, when set in motion by a string, than any thing else I can think of. They sometimes changes places from apparently indiscriminate positions, and then fall off in pairs; and after this return, with increasing ardour, in a phalanx of four and five deep, keeping up the harlequin-like motion altogether in the best time possible, and making a noise with their lips like "proo, proo, proo;" which changes successively to grunting, like the kangaroo, of which it is an imitation, and not much unlike that of a pig.

(page 61)

Note Dawson's poetic efforts to bring to life the corroboree in words, with "bawling" sounds, "phalanx" movements, and "harlequin-like motion". Modern-day writers probably wouldn't bother to go to such lengths, instead assuming that their audience is familiar with the sights and sounds in question (at the very least, from TV shows). Dawson, who was writing for a Victorian English audience, didn't enjoy this luxury.

Families

In an era when most "white fellas" in the Colony were irrevocably destroying traditional Aboriginal family ties (a practice that was to continue well into the 20th century), Dawson was appreciating and making note of the finer details that he witnessed:

They are remarkably fond of their children, and when the parents die, the children are adopted by the unmarried men and women, and taken the greatest care of.

(page 68)

He also observed the prevalence of monogamy amongst the tribes he encountered:

The husband and wife are in general remarkably constant to each other, and it rarely happens that they separate after having considered themselves as man and wife; and when an elopement or the stealing of another man's gin [wife] takes place, it creates great, and apparently lasting uneasiness in the husband.

(page 154)

As well as the enduring bonds between parents and children:

The parents retain, as long as they live, an influence over their children, whether married or not – I then asked him the reason of this [separating from his partner], and he informed me his mother did not like her, and that she wanted him to choose a better.

(page 315)

Dawson made note of the good and the bad; in the case of families, he condoned the prevalence of domestic violence towards women in the Aboriginal tribes:

On our first coming here, several instances occurred in our sight of the use of this waddy [club] upon their wives … When the woman sees the blow coming, she sometimes holds her head quietly to receive it, much like Punch and his wife in the puppet-shows; but she screams violently, and cries much, after it has been inflicted. I have seen but few gins [wives] here whose heads do not bear the marks of the most dreadful violence of this kind.

(page 66)

Clothing

Some comical accounts of how the Aborigines took to the idea of clothing in the early days:

They are excessively fond of any part of the dress of white people. Sometimes I see them with an old hat on: sometimes with a pair of old shoes, or only one: frequently with an old jacket and hat, without trowsers: or, in short, with any garment, or piece of a garment, that they can get.

(page 75)

They usually reacted well to gifts of garments:

On the following morning I went on board the schooner, and ordered on shore a tomahawk and a suit of slop clothes, which I had promised to my friend Ben, and in which he was immediately dressed. They consisted of a short blue jacket, a checked shirt, and a pair of dark trowsers. He strutted about in them with an air of good-natured importance, declaring that all the harbour and country adjoining belonged to him. "I tumble down [born] pickaninny [child] here," he said, meaning that he was born there. "Belonging to me all about, massa; pose you tit down here, I gib it to you." "Very well," I said: "I shall sit down here." "Budgeree," (very good,) he replied, "I gib it to you;" and we shook hands in ratification of the friendly treaty.

(page 12)

Death and religion

Yet another topic which was scarcely investigated by Dawson's colonial peers – and which we now know to have been of paramount importance in all Aborigines' belief systems — rituals regarding death and mourning:

… when any of their relations die, they show respect for their memories by plastering their heads and faces all over with pipe-clay, which remains till it falls off of itself. The gins [wives] also burn the front of the thigh severely, and bind the wound up with thin strips of bark. This is putting themselves in mourning. We put on black; they put on white: so that it is black and white in both cases.

(page 74)

The Aborigines that Dawson became acquainted with, were convinced that the European settlers were re-incarnations of their ancestors; this belief was later found to be fairly widespread amongst Australia's indigenous peoples:

I cannot learn, precisely, whether they worship any God or not; but they are firm in their belief that their dead friends go to another country; and that they are turned into white men, and return here again.

(page 74)

Dawson appears to have debated this topic at length with the tribespeople:

"When he [the devil] makes black fellow die," I said, "what becomes of him afterwards?" "Go away Englat," (England,) he answered, "den come back white pellow." This idea is so strongly impressed upon their minds, that when they discover any likeness between a white man and any one of their deceased friends, they exclaim immediately, "Dat black pellow good while ago jump up white pellow, den come back again."

(page 158)

Inter-tribe relations

During his time with the Worimi and other tribes, Dawson observed many of the details of how neighbouring tribes interacted, for example, in the case of inter-tribal marriage:

The blacks generally take their wives from other tribes, and if they can find opportunities they steal them, the consent of the female never being made a question in the business. When the neighbouring tribes happen to be in a state of peace with each other, friendly visits are exchanged, at which times the unmarried females are carried off by either party.

(page 153)

In one chapter, Dawson gives an amusing account of how the Worimi slandered and villainised another tribe (the Myall people), with whom they were on unfriendly terms:

The natives who domesticate themselves amongst the white inhabitants, are aware that we hold cannibalism in abhorrence; and in speaking of their enemies, therefore, to us, they always accuse them of this revolting practice, in order, no doubt, to degrade them as much as possible in our eyes; while the other side, in return, throw back the accusation upon them. I have questioned the natives who were so much with me, in the closest manner upon this subject, and although they persist in its being the practice of their enemies, still they never could name any particular instances within their own knowledge, but always ended by saying: "All black pellow been say so, massa." When I have replied, that Myall black fellows accuse them of it also, the answer has been, "Nebber! nebber black pellow belonging to Port Tebens, (Stephens;) murry [very] corbon [big] lie, massa! Myall black pellows patter (eat) always."

(page 125)

The book also explains that the members of a given tribe generally kept within their own ancestral lands, and that they were reluctant and fearful of too-often making contact with neighbouring tribes:

… the two natives who had accompanied them had become frightened at the idea of meeting strange natives, and had run away from them about the middle of their journey …

(page 24)

Relations with colonists

Throughout the book, general comments are made that insinuate the fault and the aggression in general of "white fella" in the Colony:

The natives are a mild and harmless race of savages; and where any mischief has been done by them, the cause has generally arisen, I believe, in bad treatment by their white neighbours. Short as my residence has been here, I have, perhaps, had more intercourse with these people, and more favourable opportunities of seeing what they really are, than any other person in the colony.

(page 57)

Dawson provides a number of specific examples of white aggression towards the Aborigines:

The natives complained to me frequently, that "white pellow" (white fellows) shot their relations and friends; and showed me many orphans, whose parents had fallen by the hands of white men, near this spot. They pointed out one white man, on his coming to beg some provisions for his party up the river Karuah, who, they said, had killed ten; and the wretch did not deny it, but said he would kill them whenever he could.

(page 58)

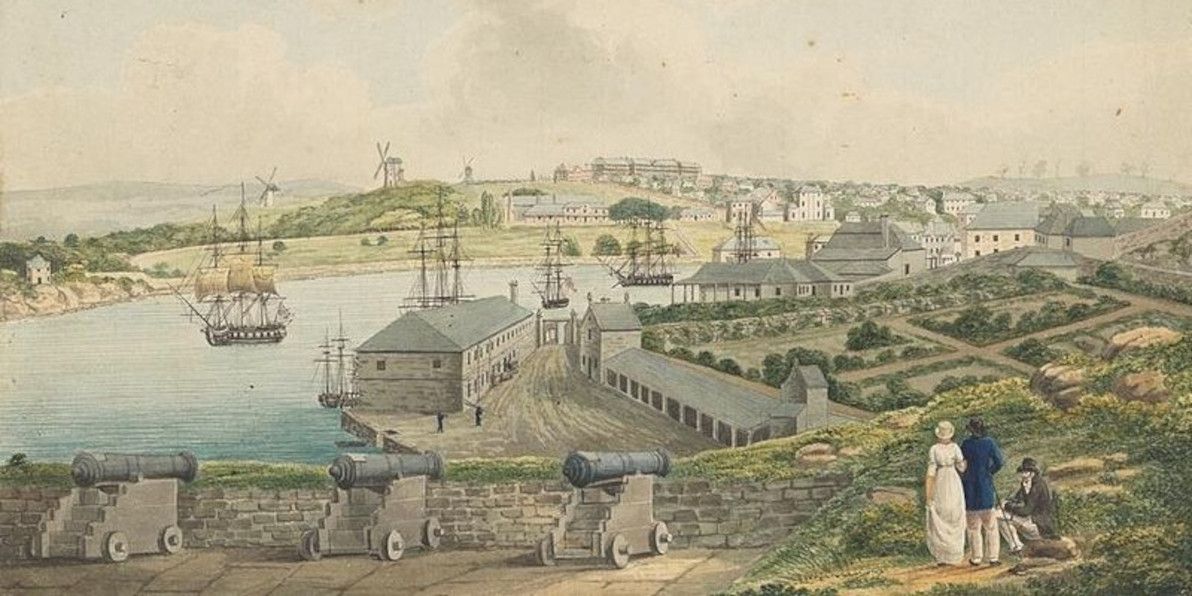

Sydney

As a modern-day Sydneysider myself, I had a good chuckle reading Dawson's account of his arrival for the first time in Sydney, in 1826:

There had been no arrival at Sydney before us for three or four months. The inhabitants were, therefore, anxious for news. Parties of ladies and gentlemen were parading on the sides of the hills above us, greeting us every now and then, as we floated on; and as soon as we anchored, (which was on a Sunday,) we were boarded by numbers of apparently respectable people, asking for letters and news, as if we had contained the budget of the whole world.

(page 46)

Image source: Wikipedia.

No arrival in Sydney, from the outside world, for "three or four months"?! Who would have thought that a backwater penal town such as this, would one day become a cosmopolitan world city, that sees a jumbo jet land and take off every 5 minutes, every day of the week? Although, it seems that even back then, Dawson foresaw something of Sydney's future:

On every side of the town [Sydney] houses are being erected on new ground; steam engines and distilleries are at work; so that in a short time a city will rise up in this new world equal to any thing out of Europe, and probably superior to any other which was ever created in the same space of time.

(page 47)

And, even back then, there were some (like Dawson) who preferred to get out of the "rat race" of Sydney town:

Since my arrival I have spent a good deal of time in the woods, or bush, as it is called here. For the last five months I have not entered or even seen a house of any kind. My habitation, when at home, has been a tent; and of course it is no better when in the bush.

(page 48)

Image source: NSW National Parks.

There's still a fair bit of bush all around Sydney; although, sadly, not as much as there was in Dawson's day.

General remarks

Dawson's impression of the Aborigines:

I was much amused at this meeting, and above all delighted at the prompt and generous manner in which this wild and untutored man conducted himself towards his wandering brother. If they be savages, thought I, they are very civil ones; and with kind treatment we have not only nothing to fear, but a good deal to gain from them. I felt an ardent desire to cultivate their acquaintance, and also much satisfaction from the idea that my situation would afford me ample opportunities and means for doing so.

(page 11)

Nomadic nature of the tribes:

When away from this settlement, they appear to have no fixed place of residence, although they have a district of country which they call theirs, and in some part of which they are always to be found. They have not, as far as I can learn, any king or chief.

(page 63)

Tribal punishment:

I have never heard but of one punishment, which is, I believe, inflicted for all offences. It consists in the culprit standing, for a certain time, to defend himself against the spears which any of the assembled multitude think proper to hurl at him. He has a small target [shield] … and the offender protects himself so dexterously by it, as seldom to receive any injury, although instances have occurred of persons being killed.

(page 64)

Generosity of Aborigines (also illustrating their lack of a concept of ownership / personal property):

They are exceedingly kind and generous towards each other: if I give tobacco or any thing else to any man, it is divided with the first he meets without being asked for it.

(page 68)

Ability to count / reckon:

They have no idea of numbers beyond five, which are reckoned by the fingers. When they wish to express a number, they hold up so many fingers: beyond five they say, "murry tousand," (many thousands.)

(page 75)

Protocol for returning travellers in a tribe:

It is not customary with the natives of Australia to shake hands, or to greet each other in any way when they meet. The person who has been absent and returns to his friends, approaches them with a serious countenance. The party who receives him is the first to speak, and the first questions generally are, where have you been? Where did you sleep last night? How many days have you been travelling? What news have you brought? If a member of the tribe has been very long absent, and returns to his family, he stops when he comes within about ten yards of the fire, and then sits down. A present of food, or a pipe of tobacco is sent to him from the nearest relation. This is given and received without any words passing between them, whilst silence prevails amongst the whole family, who appear to receive the returned relative with as much awe as if he had been dead, and it was his spirit which had returned to them. He remains in this position perhaps for half an hour, till he receives a summons to join his family at the fire, and then the above questions are put to him.

(page 132)

Final thoughts

The following pages are not put forth to gratify the vanity of authorship, but with the view of communicating facts where much misrepresentation has existed, and to rescue, as far as I am able, the character of a race of beings (of whom I believe I have seen more than any other European has done) from the gross misrepresentations and unmerited obloquy that has been cast upon them.

(page xiii)

Dawson wasn't exactly modest, in his assertion of being the foremost person in the Colony to make a fair representation of the Aborigines; however, I'd say his assertion is quite accurate. As far as I know, he does stand out as quite a solitary figure for his time, in his efforts to meaningfully engage with the tribes of the greater Sydney region, and to document them in a thorough and (relatively) unprejudiced work of prose.

I would therefore recommend those who would place the Australian natives on the level of brutes, to reflect well on the nature of man in his untutored state in comparison with his more civilized brother, indulging in endless whims and inconsistencies, before they venture to pass a sentence which a little calm consideration may convince them to be unjust.

(page 152)

Dawson's criticism of the prevailing attitudes was scathing, although it was clearly criticism that was ignored and unheeded by his contemporaries.

It is not sufficient merely as a passing traveller to see an aboriginal people in their woods and forests, to form a just estimate of their real character and capabilities … To know them well it is necessary to see much more of them in their native wilds … In this position I believe no man has ever yet been placed, although that in which I stood approached more nearly to it than any other known in that country.

(page 329)

With statements like this, Dawson is inviting his fellow colonists to "go bush" and to become acquainted with an Aboriginal tribe, as he did. From others' accounts of the era, those who followed in his footsteps were few and far between.

I have seen the natives from the coast far south of Sydney, and thence to Morton Bay (sic), comprising a line of coast six or seven hundred miles; and I have also seen them in the interior of Argyleshire and Bathurst, as well as in the districts of the Hawkesbury, Hunter's River, and Port Stephens, and have no reason whatever to doubt that they are all the same people.

(page 336)

So, why has a man and a book with so much to say about early contact with the Aborigines, lain largely forgotten and abandoned by the fickle sands of history? Probably the biggest reason, is that Dawson was just a common man. Sure, he was the first agent of AACo: but he was no intrepid explorer, like Burke and Wills; nor an important governor, like Arthur Phillip or Lachlan Macquarie. While the diaries and letters of bigwigs like these have been studied and re-published constantly, not everyone can enjoy the historical limelight.

No doubt also a key factor, was that Dawson ultimately fell out badly with the powerful Macarthur family, who were effectively his employers during his time in Port Stephens. The Present State of Australia is riddled with thinly veiled slurs at the Macarthurs, and it's quite likely that this guaranteed the book's not being taken seriously by anyone, in the Colony or elsewhere, for a long time.

Dawson's work is, in my opinion, an outstanding record of indigenous life in Australia, at a time when the ancient customs and beliefs were still alive and visible throughout most of present-day NSW. It also illustrates the human history of a geographically beautiful region that's quite close to my heart. Like many Sydneysiders, I've spent several summer holidays at Port Stephens during my life. I've also been camping countless times at nearby Myall Lakes; and I have some very dear family friends in Booral, a small town which sits alongside the Karuah River just upstream from Port Stephens (and which also falls within Worimi country).

Image source: State Library of New South Wales.

In leaving as a legacy his narrative of the Worimi people and their neighbours (which is, as far as I know, the only surviving first-hand account of these people from the coloial era of any significance), I believe that Dawson's work should be lauded and celebrated. At a time when the norm for bush settlers was to massacre and to wreak havoc upon indigenous peoples, Dawson instead chose to respect and to make friends with those that he encountered.

Personally, I think the honour of "first anthropologist of the Aborigines" is one that Dawson can rightly claim (although others may feel free to dispute this). Descendants of the Worimi live in the Port Stephens area to this day; and I hope that they appreciate Dawson's tribute, as no doubt the spirits of their ancestors do.

]]>The Oxus region is home to archaeological relics of grand civilisations, most notably of ancient Bactria, but also of Chorasmia, Sogdiana, Margiana, and Hyrcania. However, most of these ruined sites enjoy far less fame, and are far less well-studied, than comparable relics in other parts of the world.

I recently watched an excellent documentary series called Alexander's Lost World, which investigates the history of the Oxus region in-depth, focusing particularly on the areas that Alexander the Great conquered as part of his legendary military campaign. I was blown away by the gorgeous scenery, the vibrant cultural legacy, and the once-majestic ruins that the series featured. But, more than anything, I was surprised and dismayed at the extent to which most of the ruins have been neglected by the modern world – largely due to the region's turbulent history of late.

Image source: Stantastic: Back to Uzbekistan (Khiva).

This article has essentially the same aim as that of the documentary: to shed more light on the ancient cities and fortresses along the Oxus and nearby rivers; to get an impression of the cultures that thrived there in a bygone era; and to explore the climate change and the other forces that have dramatically affected the region between then and now.

Getting to know the rivers

First and foremost, an overview of the major rivers in question. Understanding the ebbs and flows of these arteries is critical, as they are the lifeblood of a mostly arid and unforgiving region.

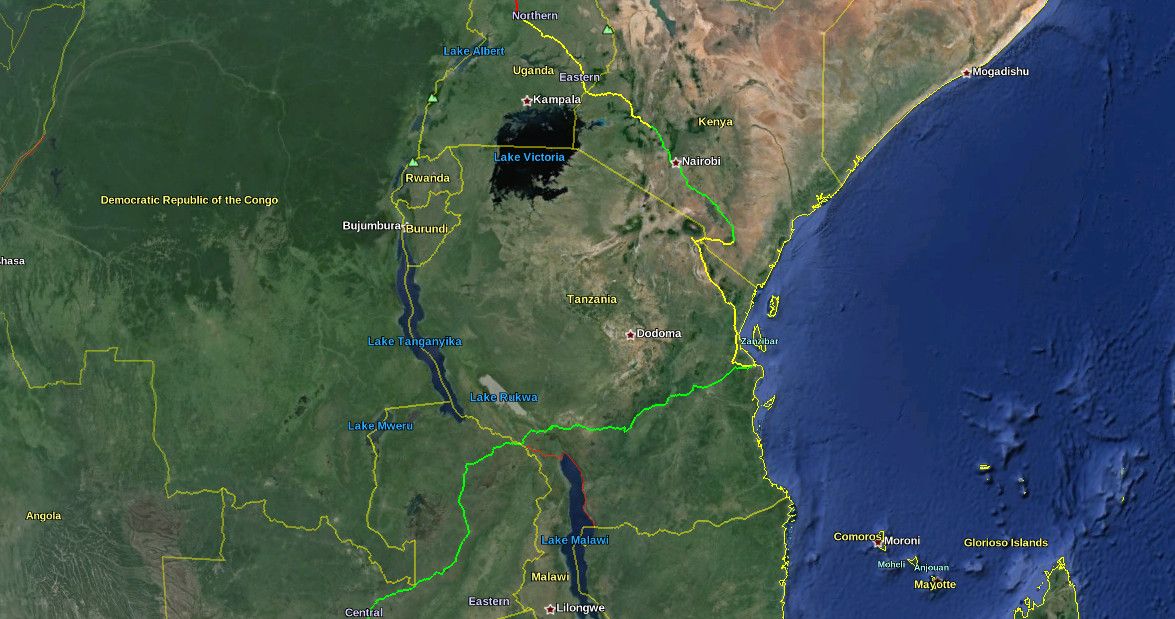

Map: Forgotten realms of the Oxus region (Google Maps Engine). Satellite imagery courtesy of Google Earth.

The Oxus is the largest river (by water volume) in Central Asia. Due to various geographical factors, it's also changed its course more times (and more dramatically) than any other river in the region, and perhaps in the world.

The source of the Oxus is the Wakhan river, which begins at Baza'i Gonbad at the eastern end of Afghanistan's remote Wakhan Corridor, often nicknamed "The Roof of the World". This location is only 40km from the tiny and seldom-crossed Sino-Afghan border. Although the Wakhan river valley has never been properly "civilised" – neither by ancient empires nor by modern states (its population is as rugged and nomadic today as it was millenia ago) – it has been populated continuously since ancient times.

Next in line downstream is the Panj river, which begins where the Wakhan and Pamir rivers meet. For virtually its entire length, the Panj follows the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border; and it winds a zig-zag course through rugged terrain for much of its course, until it leaves behind the modern-day Badakhstan province towards its end. Like the Wakhan, the mountainous upstream part of the Panj was never truly conquered; however, the more accessible downstream part was the eastern frontier of ancient Bactria.

Image soure: Photos Khandud (Hava Afghanistan).

The Oxus proper begins where the Panj and Vakhsh rivers meet, on the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border. It continues along the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan border, and then along the Afghanistan-Turkmenistan border, until it enters Turkmenistan where the modern-day Karakum Canal begins. The river's course has been fairly stable along this part of the route throughout recorded history, although it has made many minor deviations, especially further downstream where the land becomes flatter. This part of the river was the Bactrian heartland in antiquity.

The rest of the river's route – mainly through Turkmenistan, but also hugging the Uzbek border in sections, and finally petering out in Uzbekistan – traverses the flat, arid Karakum Desert. The course and strength of the river down here has changed constantly over the centuries; for this reason, the Oxus has earned the nickname "the mad river". In ancient times, the Uzboy river branched off from the Oxus in northern Turkmenistan, and ran west across the desert until (arguably) emptying into the Caspian Sea. However, the strength of the Uzboy gradually lessened, until the river completely perished approximately 400 years ago. It appears that the Uzboy was considered part of the Oxus (and was given no name of its own) by many ancient geographers.

The Oxus proper breaks up into an extensive delta once in Uzbekistan; and for most of recorded history, it emptied into the Aral Sea. However, due to an aggressive Soviet-initiated irrigation campaign since the 1950s (the culmination of centuries of Russian planning and dreaming), the Oxus delta has rescinded significantly, and the river's waters fizzle out in the desert before reaching the sea. This is one of the major causes of the death of the Aral Sea, one of the worst environmental disasters on the planet.

Although geographically separate, the nearby Murghab river is also an important part of the cultural and archaeological story of the Oxus region (its lower reaches in modern-day Turkmenistan, at least). From its confluence with the Kushk river, the Murghab meanders gently down through semi-arid lands, before opening into a large delta that fans out optimistically into the unforgiving Karakum desert. The Murghab delta was in ancient times the heartland of Margiana, an advanced civilisation whose heyday largely predates that of Bactria, and which is home to some of the most impressive (and under-appreciated) archaeological sites in the region.

I won't be covering it in this article, as it's a whole other landscape and a whole lot more history; nevertheless, I would be remiss if I failed to mention the "sister" of the Oxus, the Syr Darya river, which was in antiquity known by its Greek name as the Jaxartes, and which is the other major artery of Central Asia. The source of the Jaxartes is (according to some) not far from that of the Oxus, high up in the Pamir mountains; from there, it runs mainly north-west through Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and then (for more than half its length) Kazakhstan, before approaching the Aral Sea from the east. Like the Oxus, the present-day Jaxartes also peters out before reaching the Aral; and since these two rivers were formerly the principal water sources of the Aral, that sea is now virtually extinct.

Hyrcania

Having finished tracing the rivers' paths from the mountains to the desert, I will now – Much like the documentary – explore the region's ancient realms the other way round, beginning in the desert lowlands.

The heartland of Hyrcania (more often absorbed into a map of ancient Parthia, than given its own separate mention) – in ancient times just as in the present-day – is Golestan province, Iran, which is a fertile and productive area on the south-west shores of the Caspian. This part of Hyrcania is actually outside of the Oxus region, and so falls off this article's radar. However, Hyrcania extended north into modern-day Turkmenistan, reaching the banks of the then-flowing Uzboy river (which was ambiguously referred to by Greek historians as the "Ochos" river).

Settlements along the lower Uzboy part of Hyrcania (which was on occasion given a name of its own, Nesaia) were few. The most notable surviving ruin there is the Igdy Kala fortress, which dates to approximately the 4th century BCE, and which (arguably) exhibits both Parthian and Chorasmian influence. Very little is known about Igdy Kala, as the site has seldom been formally studied. The question of whether the full length of the Uzboy ever existed remains unresolved, particularly regarding the section from Sarykamysh Lake to Igdy Kala.

By including Hyrcania in the Oxus region, I'm tentatively siding with those that assert that the "greater Uzboy" did exist; if it didn't (i.e. if the Uzboy finished in Sarykamysh Lake, and if the "lower Uzboy" was just a small inlet of the Caspian Sea), then the extent of cultural interchange between Hyrcania and the actual Oxus realms would have been minimal. In the documentary, narrator David Adams is quite insistent that the Oxus was connected to the Caspian in antiquity, making frequent reference to the works of Patrocles; while this was quite convenient for the documentary's hypothesis that the Oxo-Caspian was a major trade route, the truth is somewhat less black-and-white.

Chorasmia

North-east of Hyrcania, crossing the lifeless Karakum desert, lies Chorasmia, better known for most of its history as Khwarezm. Chorasmia lies squarely within the Oxus delta; although the exact location of its capitals and strongholds has shifted considerably over the centuries, due to political upheavals and due to changes in the delta's course. In antiquity (particularly in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE), Chorasmia was a vassal state of the Achaemenid Persian empire, much like the rest of the Oxus region; the heavily Persian-influenced language and culture of Chorasmia, which can still be faintly observed in modern times, harks back to this era.

This region was strongest in medieval times, and its medieval capital at the present-day ghost city of Konye-Urgench – known in its heyday as Gurganj – was Chorasmia's most significant seat of power. Gurganj was abandoned in the 16th century CE, when the Oxus changed course and left the once-fertile city and surrounds without water.

It's unknown exactly where antiquity-era Chorsamia was centred, although part of the ruins of Kyrk Molla at Gurganj date back to this period, as do part of the ruins of Itchan Kala in present-day Khiva (which was Khwarezm's capital from the 17th to the 20th centuries CE). Probably the most impressive and best-preserved ancient ruins in the region, are those of the Ayaz Kala fortress complex, parts of which date back to the 4th century BCE. There are numerous other "Kala" (the Chorasmian word for "fortress") nearby, including Toprak Kala and Kz'il Kala.

One of the less-studied sites – but by no means a less significant site – is Dev-kesken Kala, a fortress lying due west of Konye-Urgench, on the edge of the Ustyurt Plateau, overlooking the dry channel of the former upper Uzboy river. Much like Konye-Urgench (and various other sites in the lower Oxus delta), Dev-kesken Kala was abandoned when the water stopped flowing, in around the 16th century CE. The city was formerly known as Vazir, and it was a thriving hub of medieval Khwarezm. Also like other sites, parts of the fortress date back to the 4th century BCE.

Image source: Karakalpak: Devkesken qala and Vazir.

I should also note that Dev-kesken Kala was one of the most difficult archaeological sites (of all the sites I'm describing in this article) to find information online for. I even had to create the Dev-Kesken Wikipedia article, which previously didn't exist (my first time creating a brand-new page there). The site was also difficult to locate on Google Earth (should now be easier, the co-ordinates are saved on the Wikipedia page). The site is certainly under-studied and under-visited, considering its distinctive landscape and its once-proud history; however, it is remote and difficult to access, and I understand that this Uzbek-Turkmen frontier area is also rather unsafe, due to an ongoing border dispute.

Margiana

South of Chorasmia – crossing the Karakum desert once again – one will find the realm that in antiquity was known as Margiana (although that name is simply the hellenised version of the original Persian name Margu). Much like Chorasmia, Margiana is centred on a river delta in an otherwise arid zone; in this case, the Murghab delta. And like the Oxus delta, the Murghab delta has also dried up and rescinded significantly over the centuries, due to both natural and human causes. Margiana lies within what is present-day southern Turkmenistan.

Although the Oxus doesn't run through Margiana, the realm is nevertheless part of the Oxus region (more surely so than Hyrcania, through which a former branch of the Oxus arguably runs), for a number of reasons. Firstly, it's geographically quite close to the Oxus, with only about 200km of flat desert separating the two. Secondly, the Murghab and the Oxus share many geographical traits, such as their arid deltas (as mentioned above), and also their habit of frequently and erratically changing course. Lastly, and most importantly, there is evidence of significant cultural interchange between Margiana and the other Oxus realms throughout civilised history.

The political centre of Margiana – in the antiquity period and for most of the medieval period, too – was the city of Merv, which was known then as Gyaur Kala (and also briefly by its hellenised name, Antiochia Margiana). Today, Merv is one of the largest and best-preserved archaeological sites in all the Oxus region, although most of the visible ruins are medieval, and the older ruins still lie largely buried underneath. The site has been populated since at least the 5th century BCE.

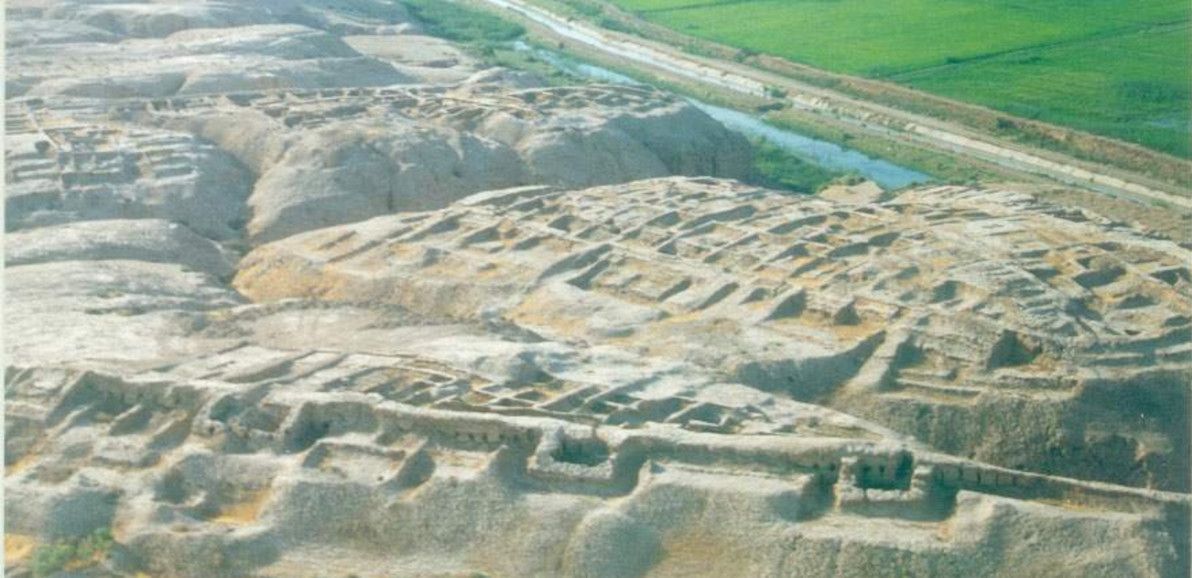

Although Merv was Margiana's capital during the Persian and Greek periods, the site of most significance around here is the far older Gonur Tepe. The site of Gonur was completely unknown to modern academics until the 1970s, when the legendary Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi discovered it (Sarianidi sadly passed away less than a year ago, aged 84). Gonur lies in what is today the parched desert, but what was – in Gonur's heyday, in approximately 2,000 BCE – well within the fertile expanse of the then-greater Murghab delta.

Image source: Boskawola.

Gonur was one of the featured sites in the documentary series – and justly so, because it's the key site of the so-called Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. It's also a prime example of a "forgotten realm" in the region: to this day, few tourists and journalists have ever visited it (David Adams and his crew were among those that have made the arduous journey); and, apart from Sarianidi (who dedicated most of his life to studying Gonur and nearby ruins), few archaeologists have explored the site, and insufficient effort is being made by authorities and by academics to preserve the crumbling ruins. All this is a tragedy, considering that some have called for bronze-age Margiana to be added to the list of the classic "cradles of civilisation", which includes Egypt, Babylon, India, and China.

There are many other ruins in Margiana that were part of the bronze-age culture centred in Gonur. One of the other more promiment sites is Altyn Tepe, which lies about 200km south-west of Gonur, still within Turkmenistan but close to the Iranian border. Altyn Tepe, like Gonur, reached its zenith around 2,000 BCE; the site is characterised by a large Babylon-esque ziggurat. Altyn Tepe was also studied extensively by Sarianidi; and it too has been otherwise largely overlooked during modern times.

Sogdiana

Crossing the Karakum desert again (for the last time in this article) – heading north-east from Margiana – and crossing over to the northern side of the Oxus river, one may find the realm that in antiquity was known as Sogdiana (or Sogdia). Sogdiana principally occupies the area that is modern-day southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan.

The Sogdian heartland is the fertile valley of the Zeravshan river (old Persian name), which was once known by its Greek name, as the Polytimetus, and which has also been called the Sughd, in honour of its principal inhabitants (modern-day Tajikistan's Sughd province, through which the river runs, likewise honours them).

The Zeravshan's source is high in the mountains near the Tajik-Kyrgyz border, and for its entire length it runs west, passing through the key ancient Sogdian cities of Panjakent, Samarkand (once known as Maracanda), and Bukhara (which all remain vibrant cities to this day), before disappearing in the desert sands approaching the Uzbek-Turkmen border. The Zeravshan probably reached the Oxus and emptied into it – once upon a time – near modern-day Türkmenabat, which in antiquity was known as Amul, and in medieval times as Charjou. For most of its history, Amul lay just beyond the frontiers of Sogdiana, and it was the crossroads of all the principal realms of the Oxus region mentioned in this article.

Although Sogdiana is an integral part of the Oxus region, and although it was a dazzling civilisation in antiquity (indeed, it was arguably the most splendid of all the Oxus realms), I'm only mentioning it in this article for completeness, and I will refrain from exploring its archaeology in detail. (You may also have noted that the Zeravshan river and the Sogdian cities are missing from my custom map of the region). This is because I don't consider Sogdiana to be "forgotten", in anywhere near the sense that the other realms are "forgotten".

The key Sogdian sites – particularly Samarkand and Bukhara, which are both today UNESCO-listed – enjoy international fame; they have been studied intensively by modern academics; and they are the biggest tourist attractions in all of Central Asia. Apart from Sogdiana's prominence in Silk Road history, and its impressive and well-preserved architecture, the relative safety and stability of Uzbekistan – compared with its fellow Oxus-region neighbours Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan – has resulted in the Sogdian heartland receiving the attention it deserves from the curious modern world.

Also – putting aside its "not forgotten" status – the partial exclusion (or, perhaps more accurately, the ambivalent inclusion) of Sogdiana from the Oxus region has deep historical roots. Going back to Achaemenid Persian times, Sogdiana was the extreme northern frontier of Darius's empire. And when the Greeks arrived and began to exert their influence, Sogdiana was known as Transoxiana, literally meaning "the land across the Oxus". Thus, from the point of view of the two great powers that dominated the region in antiquity – the Persians and the Greeks – Sogdiana was considered as the final outpost: a buffer between their known, civilised sphere of control; and the barbarous nomads who dwelt on the steppes beyond.

Bactria

Finally, after examining the other realms of the Oxus region, we come to the land that was the region's showpiece in the antiquity period: Bactria. The Bactrian heartland can be found south of Sogdiana, separated from it by the (relatively speaking) humble Chul'bair mountain range. Bactria occupies a prime position along the Oxus river: that is, it's the first section lying downstream of overly-rugged terrain; and it's upstream enough that it remains quite fertile to this day, although it's significantly less fertile than it was millennia ago. Bactria falls principally within modern-day northern Afghanistan; but it also encroaches into southern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

Historians know more about antiquity-era Bactria than they do about the rest of the Oxus region, primarily because Bactria was better incorporated into the great empires of that age than were its neighbours, and therefore far more written records of Bactria have survived. Bactria was a semi-autonomous satrapy (province) of the Persian empire since at least the 6th century BCE, although it was probably already under Persian influence well before then. It was conquered by Alexander the Great in 328 BCE (after he had already marched through Sogdiana the year before), thus marking the start of Greco-Bactrian rule, making Bactria the easternmost hellenistic outpost of the ancient world.

However, considering its place in the narrative of these empires, and considering its being recorded by both Persian and Greek historians, surprisingly little is known about the details of ancient Bactria today. This is why the documentary was called "Alexander's Lost World". Much like its neighbours, the area comprising modern-day Bactria is relatively seldom visited and seldom studied, due to its turbulent recent history.

The first archaeological site that I'd like to discuss in this section is that of Kampyr Tepe, which lies on the northern bank of the Oxus (putting it within Uzbek territory), just downstream from modern-day Termez. Kampyr Tepe was constructed around the 4th century BCE, possibly initially as a garrison by Alexander's forces. It was a thriving city for several centuries after that. It would have been an important defensive stronghold in antiquity, lying as it does near the western frontier of Bactria proper, not far from the capital, and affording excellent views of the surrounding territory.

Image source: rusanoff – Photo of Kampyrtepa.

There is evidence that a number of different religious groups co-existed peacefully in Kampyr Tepe: relics of Hellenism, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism from similar time periods have been discovered here. The ruins themselves are in good condition, especially considering the violence and instability that has affected the site's immediate surroundings in recent history. However, the reason for the site's admirable state of preservation is also the reason for its inaccessibility: due to its border location, Kampyr Tepe is part of a sensitive Uzbek military-controlled zone, and access is highly restricted.

The capital of Bactria was the grand city of Bactra, the location of which is generally accepted to be a circular plateau of ruins touching the northern edge of the modern-day city of Balkh. These lie within the delta of the modern-day Balkh river (once known as the Bactrus river), about 70km south of where the Oxus presently flows. In antiquity, the Bactrus delta reached the Oxus and fed into it; but the modern-day Balkh delta (like so many other deltas mentioned in this article) fizzles out in the sand.

Today, the most striking feature of the ruins is the 10km-long ring of thick, high walls enclosing the ancient city. Balkh is believed to have been inhabited since at least the 27th century BCE, although most of the archaeological remains only date back to about the 4th century BCE. The ruins at Balkh are currently on UNESCO's tentative World Heritage list. It's likely that the plateau at Balkh was indeed ancient Bactra; however, this has never been conclusively proven. Modern archaeologists barely had any access to the site until 2003, due to decades of military conflict in the area. To this day, access continues to be highly restricted, for security reasons.

Image source: Hazara Association of UK.

Bactria was an important centre of Zoroastianism, and Bactra is one of (and is the most likely of) several contenders claiming to be the home of the mythical prophet Zoroaster. Tentatively related to this, is the fact that Bactra was also (possibly) once known as Zariaspa. A few historians have gone further, and have suggested that Bactra and Zariaspa were two different cities; if this is the case, then a whole new can of worms is opened, because it begs a multitude of further questions. Where was Zariaspa? Was Bactra at Balkh, and Zariaspa elsewhere? Or were Bactra and Zariaspa actually the same city… but located elsewhere?

Based on the theory of Ptolemy (and perhaps others), in the documentary David Adams strongly hypothesises that: (a) Bactra and Zariaspa were twin cities, next to each other; (b) the twin-city of Bactra-Zariaspa was located somewhere on the Oxus north of Balkh (he visits and proposes such a site, which I believe was somewhere between modern-day Termez and Aiwanj); and (c) this site, rather than Balkh, was the capital of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom that followed Alexander's conquest. While this is certainly an interesting hypothesis – and while it's true that there hasn't been nearly enough excavation or analysis done in modern times to rule it out – the evidence and the expert opinion, as it stands today, would suggest that Adams's hypothesis is wrong. As such, I think that his assertion of "the lost city of Bactra-Zariaspa" lying on the Oxus, rather than in the Bactrus delta, was stated rather over-confidently and with insufficient disclaimers in the documentary.

Upper Bactria

Although not historically or culturally distinct from the Bactrian heartland, I'm analysing "Upper Bactria" (i.e. the part of Bactria upstream of modern-day Balkh province) separately here, primarily to maintain structure in this article, but also because this farther-flung part of the realm is geographically quite rugged, in contrast to the heartland's sweeping plains.

First stop in Upper Bactria is the archaeological site of Takhti Sangin. This ancient ruin can be found on the Tajik side of the border; and since it's located at almost the exact spot where the Panj and Vakhsh rivers meet to become the Oxus, it could also be said that Takhti Sangin is the last site along the Oxus proper that I'm examining. However, much like the documentary, I'll be continuing the journey further upstream to the (contested) "source of the Oxus".

Image source: MATT: From North to South.

The principal structure at Takhti Sangin was a large Zoroastrian fire temple, which in its heyday boasted a pair of constantly-burning torches at its main entrance. Most of the remains at the site date back to the 3rd century BCE, when it became an important centre in the Greco-Bactrian kingdom (and when it was partially converted into a centre of Hellenistic worship); but the original temple is at least several centuries older than this, as attested to by various Achaemenid Persian-era relics.