It turns out that Chile has joined a small group of countries around the world, that have decided to implement a national IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) whitelist. From some quick investigation, as far as I can tell, the only other countries that boast such a system are Turkey, Azerbaijan, Colombia, and Nepal. Hardly the most venerable group of nations to be joining, in my opinion.

As someone who has been to Chile many times, all I can say is: not happy! Bringing your own mobile device, and purchasing a local SIM card, is the cheapest and the most convenient way to stay connected while travelling, and it's the go-to method for a great many tourists travelling all around the world. It beats international roaming hands-down, and it eliminates the unnecessary cost of purchasing a new local phone all the time. I really hope that the Chilean government reconsiders the need for this law, and I really hope that no more countries join this misguided bandwagon.

Image source: imgflip.

IMEI what?

In case you've never heard of an IMEI, and have no idea what it is, basically it's a unique identification code for all mobile phones worldwide. Historically, there have been no restrictions on the use of mobile handsets, in particular countries or worldwide, according to the device's IMEI code. On the contrary, what's much more common than the network blocking a device, is for the device itself to block access to all networks except one, due to it needing to be unlocked.

A number of countries have implemented IMEI blacklists, mainly in order to render stolen mobile devices useless – these countries include Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and numerous others. In my opinion, a blacklist is a much better solution than a whitelist in this domain, because it only places an administrative burden on problem devices, while all other devices on the network are presumed to be valid and authorised to connect.

Ostensibly, Chile has passed this law primarily to ensure that all mobiles imported and sold locally by retailers are capable of receiving emergency alerts (i.e. for natural disasters, particularly earthquakes and tsunamis), using a special system called SAE (Sistema de Alerta de Emergencias). In actual fact, the system isn't all that special – it's standard Cell Broadcast (CB) messaging, the vast majority of smartphones worldwide already support it, and registering IMEIs is not in any way required for it to function.

For example, the same technology is used for the Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) system in the USA, and for the Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) system in Japan, and neither of those countries have an IMEI whitelist in place. Chile uses channel 919 for its SAE broadcasts, which appears to be a standard emergency channel that's already used by The Netherlands and Israel (again, countries without an IMEI whitelist), and possibly also by other countries.

The new law is supposedly also designed to ensure (quoting the original Spanish text):

…que todos los equipos comercializados en el país informen con certeza al usuario si funcionarán o no en las diferentes localidades a lo largo de Chile, según las tecnologías que se comercialicen en cada zona geográfica.

Which translates to English as:

…that all commercially available devices in the country provide a guarantee to the user of whether they will function or not in all of the various regions throughout Chile, according to the technologies that are deployed within each geographical area.

However, that same article suggests that this is a solution to a problem that doesn't currently exist – i.e. that the vast majority of devices already work nationwide, and that Chile's mobile network technology is already sufficiently standardised nationwide. It also suggests that the real reason why this law was introduced, was simply in order to stifle the smaller, independent mobile retailers and service providers with a costly administrative burden, and thus to entrench the monopoly of Chile's big mobile companies (and there are approximately three big players on the scene).

So, it seems that the Chilean government created this law thinking purely of its domestic implications – and even those reasons are unsound, and appear to be mired in vested interests. And, as far as I can see, no thought at all was given to the gross inconvenience that this law was bound to cause, and that it is currently causing, to tourists. The fact that the Movistar Chile IMEI registration online form (which I used) requires that you enter a RUT (a Chilean national ID number, which most tourists including myself lack), exemplifies this utter obliviousness of the authorities and of the big telco companies, regarding visitors to Chile perhaps wanting to use their mobile devices as they see fit.

In summary

Chile is now one of a handful of countries where, as a tourist, despite bringing from home a perfectly good cellular device (i.e. one that's unlocked and that functions with all the relevant protocols and frequencies), the pig-headed bureaucracy of an IMEI whitelist makes the device unusable. So, my advice to anyone who plans to visit Chile and to purchase a local SIM card for your non-Chilean mobile phone: register your phone's IMEI well in advance of your trip, with one of the Chilean companies licensed to "certify" it (the procedure is at least free, for one device per person per year, and can be done online), and thus avoid the inconvenience of your device not working upon arrival in the country.

]]>

Image source: Favourite picture: Road construction in Siberia – RoadStars.

Naturally, such places also happen to be largely bereft of any other human infrastructure, such as buildings; and to be largely bereft of any human population. These are places where, in general, nothing at all is to be encountered save for sand, ice, and rock. However, that's just coincidental. My only criteria, for the purpose of this article, is a lack of roads.

Alaska

I was inspired to write this article after reading James Michener's epic novel Alaska. Before reading that book, I had only a vague knowledge of most things about Alaska, including just how big, how empty, and how inaccessible it is.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

One might think that, on account of it being part of the United States, Alaska boasts a reasonably comprehensive road network. Think again. Unlike the "Lower 48" (as the contiguous USA is referred to up there), only a small part of Alaska has roads of any sort at all, and that's the south-east corner around Anchorage and Fairbanks. And even there, the main routes are really part of the American Interstate network only on paper.

As you can see from the map, the entire western part of the state, and most of the north of the state, lack any road routes whatsoever. The north-east is also almost without roads, except for the Dalton Highway – better known locally as "The Haul Road" – which is a crude and uninhabited route for most of its length.

There has been discussion for decades about the possibility of building a road to Nome, which is the biggest settlement in western Alaska. However, such a road remains a pipe dream. It's also impossible to drive to Barrow, which is the biggest place in northern Alaska, and also the northernmost city in North America. This is despite Barrow being only about 300km west of the Dalton Highway's terminus at the Prudhoe Bay oilfields.

Road building is a trouble-fraught enterprise in Alaska, where distances are vast, population centres are few (or none), and geography / climate is harsh. In particular, building roads on permafrost (of which much of Alaska's terrain is) can be challenging, because the frozen soil expands in summer, and violently cracks whatever is on top of it. Also, while solid in winter, permafrost turns to muddy swamps in summer.

Image source: Yukon Animator.

It's no wonder, then, that for most of the far-flung outposts in northern and western Alaska, the main forms of transport are by sea or air. Where terrestrial transport is taken, it's most commonly in the form of a dog sled, and remains so to this day. In winter, Alaska's true main highways are its frozen rivers – particularly the mighty Yukon – which have been traversed by sled dogs, on foot (often with fatal results), and even by bicycle.

Canada

Much like its neighbour Alaska, northern Canada is also a vast expanse of frozen tundra that remains largely uninhabited. Considering the enormity of the area in question, Canada has actually made quite impressive progress in the building of roads further north. However, as the map illustrates, much of the north remains pristine and unblemished.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The biggest chunk of the roadless Canadian north is the territory of Nunavut. There are no roads to Nunavut (unless you count this), nor are there any linking its far-flung towns. As its Wikipedia page states, Nunavut is "the newest, largest, northernmost, and least populous territory of Canada". Nunavut's principal settlements of Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet, and Cambridge Bay can only be reached by sea or air.

Image source: Huffington Post.

The Northwest Territories is barren in many places, too. The entire eastern pocket of the Territories, bordering Nunavut and Saskatchewan (i.e. everything east of Tibbitt Lake, where the Ingraham Trail ends), has not a single road. And there are no roads north of Wrigley (where the Mackenzie Highway ends), except for the northernmost section of the Dempster Highway up to Inuvik. There are also no roads north of the Dempster Highway in Yukon Territory. And, on the other side of Canada, there are no roads in Quebec or Labrador north of Caniapiscau and the Trans-Taiga Road.

Greenland

Continuing east around the Arctic Circle, we come to Greenland, which is the largest contiguous and permanently-inhabited land mass in the world to have no roads at all between its settlements. Greenland is also the world's largest island.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The reason for the lack of road connections is the Greenland ice sheet, the second-largest body of ice in the world (after the Antarctic ice sheet), which covers 81% of the territory's surface. (And, as such, the answer to the age-old question "Is Greenland really green?", is overall "No!"). The only way to travel between Greenland's towns year-round is by air, with sea travel being possible only in summer, and dog sledding only in winter.

Svalbard

I'm generally avoiding covering small islands in this article, and am instead focusing on large continental areas. However, Svalbard (with Spitsbergen actually being the main island) is the largest island in the world – apart from islands that fall within other areas covered in this article – that has no roads between any of its settlements.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Svalbard is a Norwegian territory situated well north of the Arctic Circle. Its capital, Longyearbyen, is the northernmost city in the world. There are no roads linking Svalbard's handful of towns. Travel options involve air, sea, or snow.

Siberia

The largest geographical region of the world's largest country (Russia), and well known as a vast "frozen wasteland", it should come as no surprise that Siberia features in this article. Siberia is the last of the arctic areas that I'll be covering here (indeed, if you continue east, you'll get back to Alaska, where I started). Consisting primarily of vast tracts of taiga and tundra, Siberia – particularly further north and further east – is a sparsely inhabited land of extreme cold and remoteness.

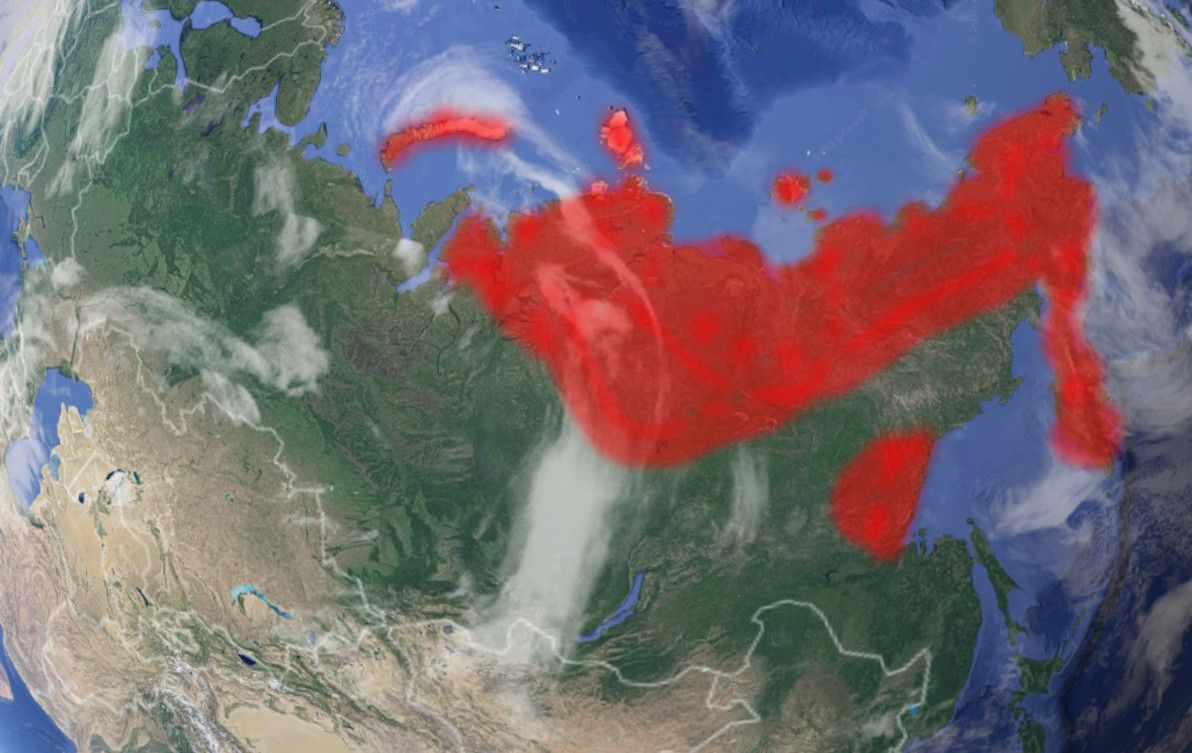

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Considering the size, the emptiness, and the often challenging terrain, Russia has actually made quite impressive achievements in building transport routes through Siberia. Starting with the late days of the Russian Empire, going strong throughout much of the Soviet Era, and continuing with the present-day Russian Federation, civilisation has slowly but surely made inroads (no pun intended) into the region.

North-west Russia – which actually isn't part of Siberia, being west of the Ural Mountains – is quite well-serviced by roads these days. There are two modern roads going north all the way to the Barents Sea: the R21 Highway to Murmansk, and the M8 route to Arkhangelsk. Further east, closer to the start of Siberia proper, there's a road up to Vorkuta, but it's apparently quite crude.

Crossing the Urals east into Siberia proper, Yamalo-Nenets has until fairly recently been quite lacking in land routes, particularly north of the capital Salekhard. However, that has changed dramatically of late in the remote (and sparsely inhabited) Yamal Peninsula, where there is still no proper road, but where the brand-new Obskaya-Bovanenkovo Railroad is operating. Purpose-built for the exploitation of what is believed to be the world's largest natural gas field, this is now the northernmost railway line in the world (and it's due to be extended even further north). Further up from Yamalo-Nenets, the islands of Novaya Zemlya are without land routes.

Image source: The Washington Post.

East of the Yamal Peninsula, the great roadless expanse of northern Siberia begins. In Krasnoyarsk Krai, the second-biggest geographical division in Russia, there are no real roads past the area more than a few hundred km's north of the city of Krasnoyarsk. Nothing, that is, except for the road and railway (until recently the world's northernmost) that reach the northern outpost of Norilsk; although neither road nor rail are properly connected to the rest of Russia.

The Sakha Republic, Russia's biggest geographical division, is completely roadless save for the main highway passing through its south-east corner, and its capital, Yakutsk. In the far north of Sakha, on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, the town of Tiksi is reckoned to be the most remote settlement in all of Russia. Here in the depths of Siberia, the main transport is via the region's mighty rivers, of which the Lena forms the backbone of Sakha. In winter, dog sleds and ice vehicles are the norm.

In the extreme north-east of Siberia, where Chukotka and the Kamchatka Peninsula can be found, there are no road routes whatsoever. Transport in these areas is solely by sea, air, or ice. The only road that comes close to these areas is the Kolyma Highway, also infamously known as the Road of Bones; this route has been improved in recent years, although it's still hair-raising for much of its length, and it's still one of the most remote highways in the world. There are also no roads to Okhotsk (which was the first and the only Russian settlement on the Pacific coast for many centuries), nor to anywhere else in northern Khabarovsk Krai.

Tibet

A part of the People's Republic of China (whether they like it or not) since 1951, Tibet has come a long way since the old days, when the entire kingdom did not have a single road. Today, China claims that 70% of all villages in Tibet are connected by road. And things have also stepped up quite a big notch, since the 2006 opening of the Trans-Tibetan Railway, which is a marvel of modern engineering, and is (at over 5,000m in one section) the new highest-altitude railway in the world.

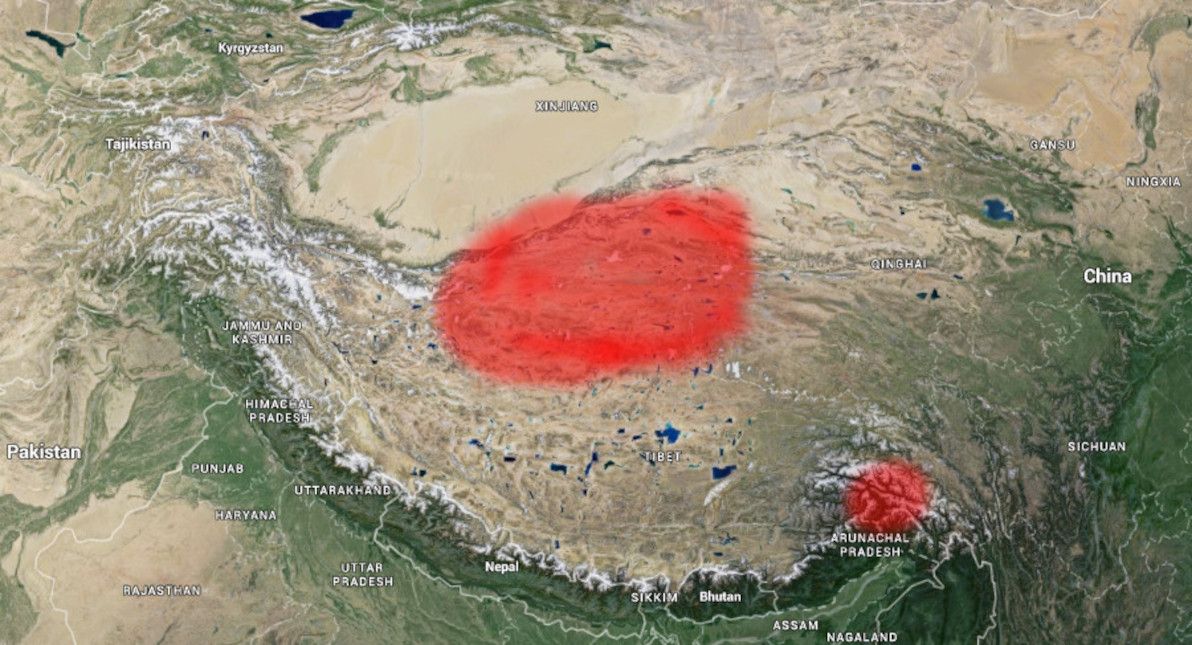

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Virtually the entire southern half of Tibet boasts a road network today. However, the central north area of the region – as well as a fair bit of adjacent terrain in neighbouring Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces – still appears to be without roads. This area also looks like it's devoid of any significant settlements, with nothing much around except high-altitude tundra.

Sahara

Leaving the (mostly icy) roadless realms of North America and Eurasia behind us, it's time to turn our attention southward, where the regions in question are more of a mixed bag. First up: the Sahara, the world's largest desert, which covers almost all of northern Africa, and which is virtually uninhabited save for its semi-arid fringes.

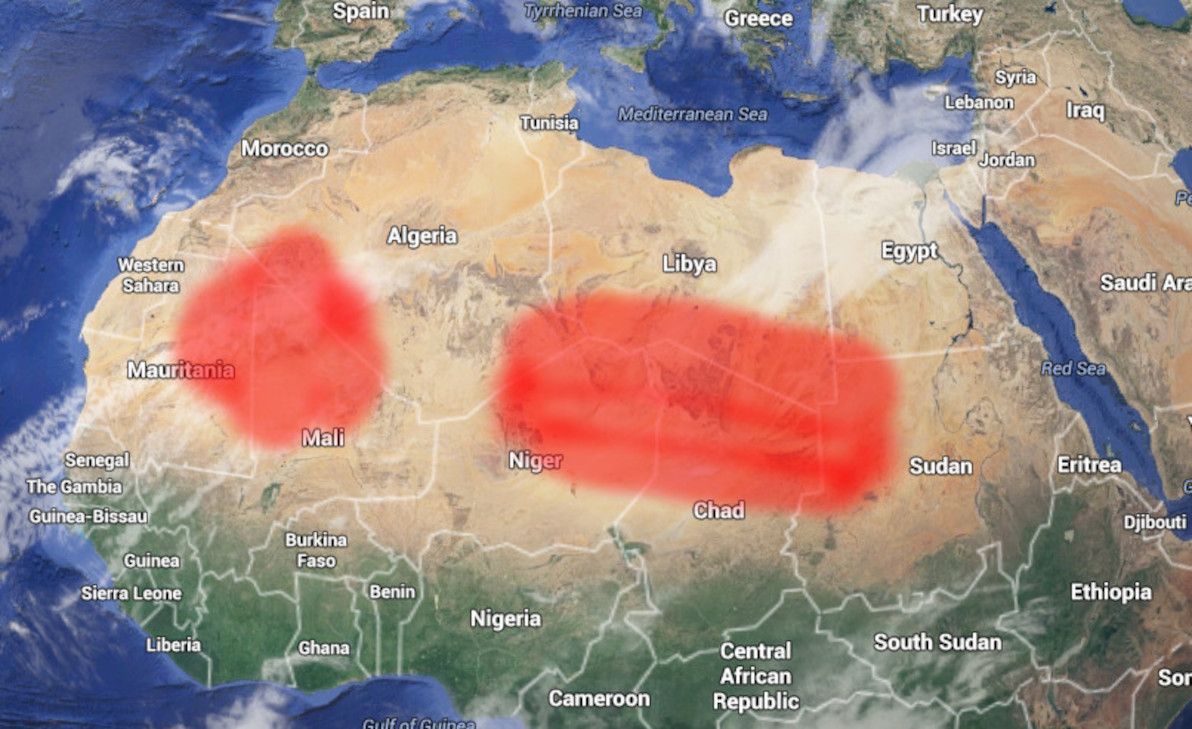

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

As the map shows, most of the parched interior of the Sahara is without roads. This includes: north-eastern Mauritania, northern Mali, south-eastern and south-western Algeria, northern Niger, southern Libya, northern Chad, north-west Sudan, and south-west Egypt. For all of the above, the only access is by air, by well-equipped 4WD convoy, or by camel caravan.

The only proper road cutting through this whole area, is the optimistically named Trans-Sahara Highway, the key part of which is the crossing from Agadez, Niger, north to Tamanrasset, Algeria. However, although most of the overall route (going all the way from Nigeria to Algeria) is paved, the section north of Agadez is still largely just a rough track through the sand, with occasional signposts indicating the way. There is also a rough track from Mali to Algeria (heading north from Kidal), but it appears to not be a proper road, even by Saharan standards.

Image source: Found the World.

I should also state (the obvious) here, namely that Saharan and Sub-Saharan Africa is not only one of the most arid and sparsely populated places on Earth, but that it's also one of the poorest, least developed, and most politically unstable places on Earth. As such, it should come as no surprise that overland travel through most of the roadless area is currently strongly discouraged, due to the security situation in many of the listed countries.

Australia

No run-down of the world's great roadless areas would be complete without including my sunburnt homeland, Australia. As I've blogged about before, there's a whole lot of nothing in the middle of this joint.

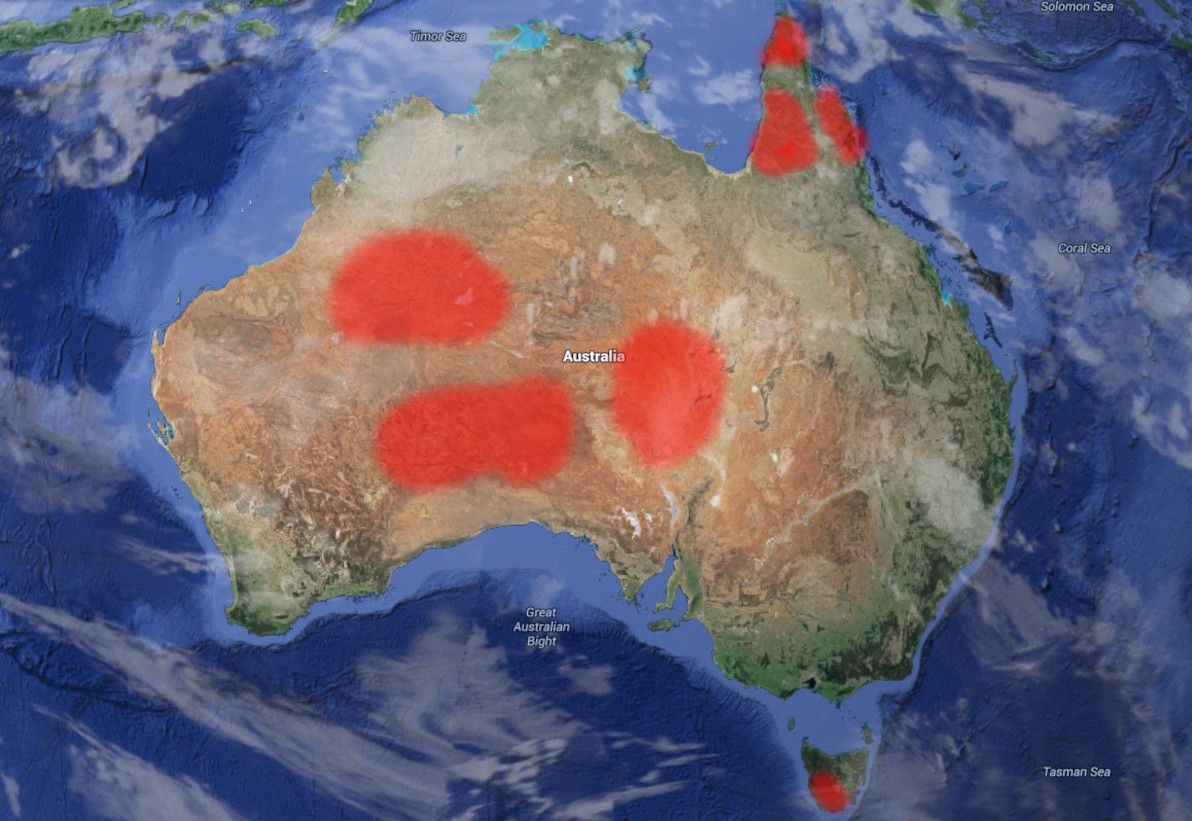

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The biggest area of Australia to still lack road routes, is the heart of the Outback, in particular most of the east of Western Australia, and neighbouring land in the Northern Territory and South Australia. This area is bisected by only a single half-decent route (running east-west), the Outback Way – a route that is almost entirely unsealed – resulting in a north and a south chunk of roadless expanse.

The north chunk is centred on the Gibson Desert, and also includes large parts of the Great Sandy Desert and the Tanami Desert. The Gibson Desert, in particular, is considered to be the most remote place in Australia, and this is evidenced by its being where the last uncontacted Aboriginal tribe was discovered – those fellas didn't come outta the bush there 'til 1984. The south chunk consists of the Great Victoria Desert, which is the largest single desert in Australia, and which is similarly remote.

After that comes the area of Lake Eyre – Australia's biggest lake and, in typical Aussie style, one that seldom has any water in it – and the Simpson Desert to its north. The closest road to Lake Eyre itself is the Oodnadatta Track, and the only road that skirts the edge of the Simpson Desert is the Plenty Highway (which is actually part of the Outback Way mentioned above).

Image source: Avalook.

On the Apple Isle of Tasmania, the entire south-west region is an uninhabited, pristine, climatically extreme wilderness, and it's devoid of any roads at all. The only access is by sea or air: even 4WD is not an option in this hilly and forested area. Tasmania's famous South Coast Track bushwalk begins at the outpost of Melaleuca, where there is nothing except a small airstrip, and which can effectively only be reached by light aircraft. Not a trip for the faint-hearted.

Finally, in the extreme north-east of Australia, Cape York Peninsula remains one of the least accessible places on the continent, and has almost no roads (particularly the closer you get to the tip). The Peninsula Development Road, going as far north as Weipa, is the only proper road in the area: it's still largely unsealed, and like all other roads in the area, is closed and/or impassable for much of the year due to flooding. Up from there, Bamaga Road and the road to the tip are little more than rough tracks, and are only navigable by experienced 4WD'ers for a few months of the year. In this neck of the woods, you'll find that crocodiles, mosquitoes, jellyfish, and mud are much more common than roads.

New Zealand

Heading east across the ditch, we come to the Land of the Long White Cloud. The South Island of New Zealand is well-known for its dazzling natural scenery: crystal-clear rivers, snow-capped mountains, jutting fjords, mammoth glaciers, and rolling hills. However, all that doesn't make for areas that are particularly easy to live in, or to construct roads through.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Essentially, the entire south-west edge of NZ's South Island is without road access. In particular, all of Fiordland National Park: the whole area south of Milford Sound, and east of Te Anau. Same deal for Mount Aspiring National Park, between Milford Sound and Jackson Bay. The only exception is Milford Sound itself, which can be accessed via the famous Homer Tunnel, an engineering feat that pierces the walls of Fiordland against all odds.

Chile

You'd think that, being such a long and thin country, getting at least one road to traverse the entire length of Chile wouldn't be so hard. Think again. Chile is the world's longest north-south country, and spans a wide range of climatic zones, from hot dry desert in the north, to glacial fjord-land in the extreme south. If you've seen Chile desde Arica hasta Punta Arenas (as I have!), then you've witnessed first-hand the geographical variety that it has to offer.

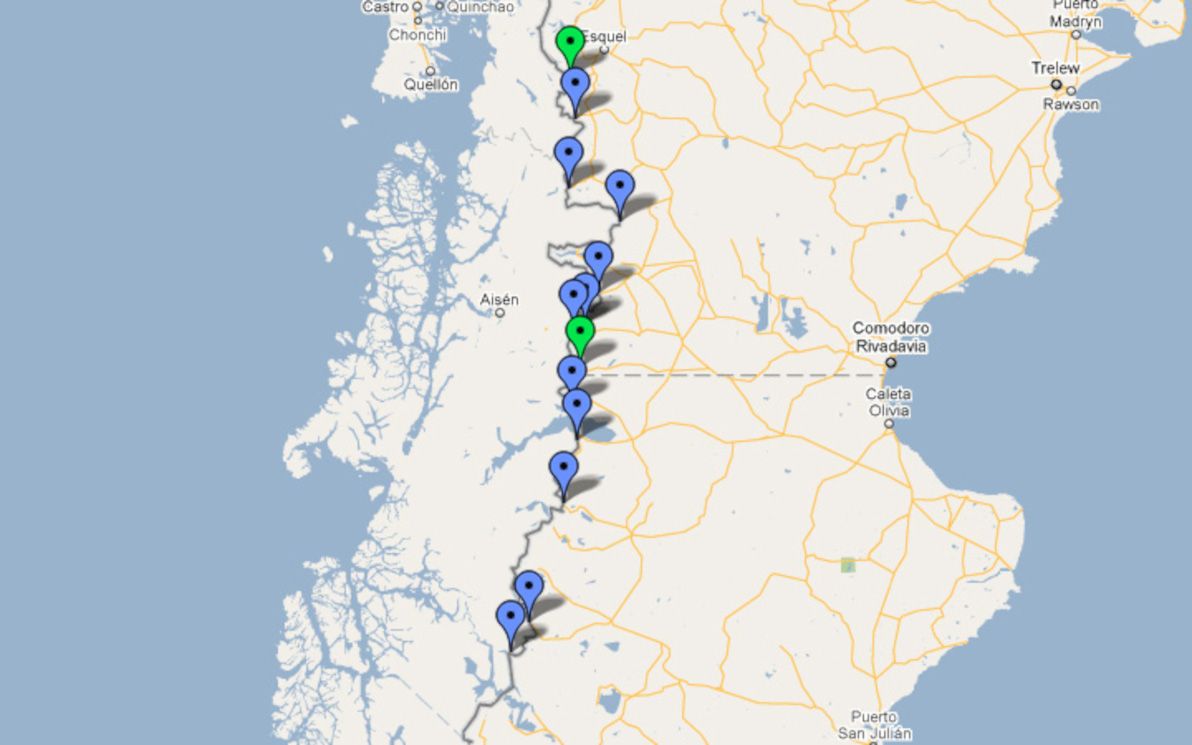

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

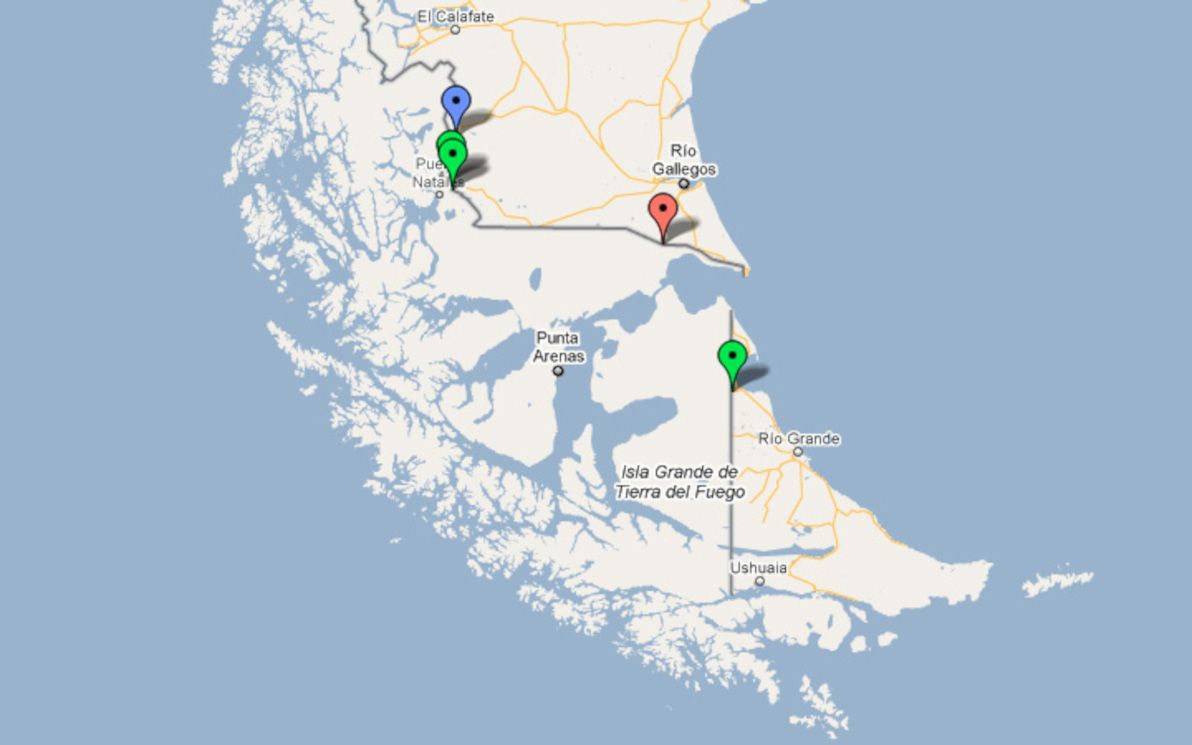

Roads can be found in all of Chile, except for one area: in the far south, between Villa O'Higgins and Torres del Paine. That is, the southern-most portion of Región de Aysén, and the northern half of Región de Magallanes, are entirely devoid of roads. This is mainly on account of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, one of the world's largest chunks of ice outside of the polar regions. This ice field was only traversed on foot, for the first time in history, as recently as 1998; it truly is one of our planet's final unconquered frontiers. No road will be crossing it anytime soon.

Image source: Mallin Colorado.

Much of the Chilean side of the island of Tierra del Fuego is also without roads: this includes most of Parque Karukinka, and all of Parque Nacional Alberto de Agostini.

The Chilean government has for many decades maintained the monumental effort of extending the Carretera Austral ever further south. The route reached its current terminus at Villa O'Higgins in 2000. The ultimate aim, of course, is to connect isolated Magallanes (which to this day can only be reached by road via Argentina) with the rest of the country. But considering all the ice, fjords, and extreme conditions in the way, it might be some time off yet.

Amazon

We now come to what is by far the most lush and life-filled place in this article: the Amazon Basin. Spanning several South American countries, the Amazon is home to the world's largest river (by water volume) and river system. Although there are some big settlements in the area (including Iquitos, the world's biggest city that's not accessible by road), in general there are more piranhas and anacondas than there are people in this jungle (the piranhas help to keep it that way!).

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Considering the challenges, quite a number of roads have actually been built in the Amazon in recent decades, particularly in the Brazilian part. The best-known of these is the Transamazônica, which – although rough and muddy as can be – has connected vast swaths of the jungle to civilisation. It should also be noted, that extensive road-building in this area is not necessarily a good thing: publicly-available satellite imagery clearly illustrates that, of the 20% of the Amazon that has been deforested to date, much of it has happened alongside roads.

The main parts of the Amazon that remain completely without roads are: western Estado do Amazonas and northern Estado do Pará in Brazil; most of north-eastern Peru (Departamento de Loreto); most of eastern Ecuador (the provinces in the Región amazónica del Ecuador); most of south-eastern Colombia (Amazonas, Vaupés, Guainía, Caquetá, and Guaviare departamentos); southern Venezuela (Estado de Amazonas); and the southern part of all the Guyanas (British Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana).

Image source: Getty Images.

The Amazon Basin probably already has more roads than it needs (or wants). In this part of the world, the rivers are the real highways – especially the Amazon itself, which has heavy marine traffic, despite being more than 5km wide in many parts (and that's in the dry season!). In fact, it's hard for terrestrial roads to compete with the rivers: for example, the BR-319 to Manaus has been virtually washed away by the jungle, and the main access to the Amazon's biggest city remains by boat.

Antarctica

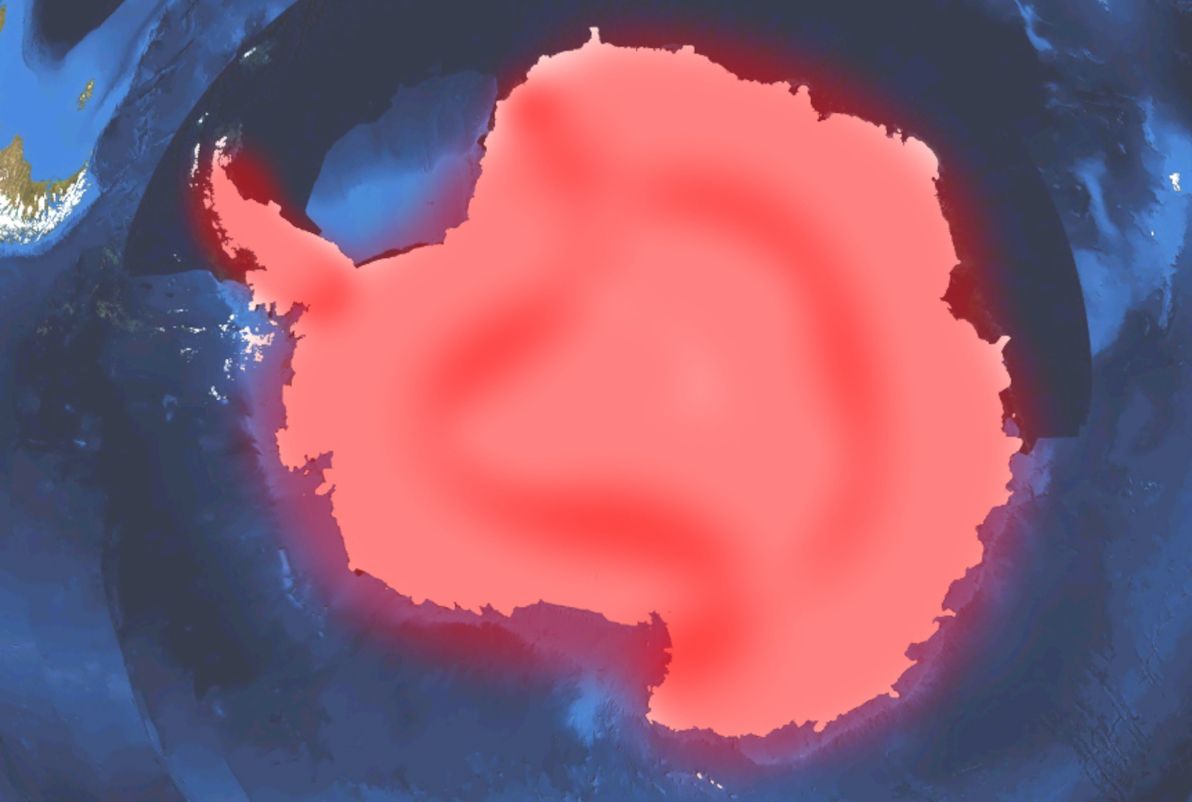

It's the world's fifth-largest continent. It's completely covered in ice. It has no permanent human population. It has no countries or (proper) territories. And it has no roads. And none of this should be a surprise to anyone!

Image source: Wikimedia Commons (red highlighting by yours truly).

As you might have guessed, not only are there no roads linking anywhere to anywhere else within Antarctica (except for ice trails), but (unlike every other area covered in this article) there aren't even any local roads within Antarctic settlements. The only regular access to Antarctica, and around Antarctica, is by air; even access by ship is difficult without helicopter support.

Where to?

There you have it: an overview of some of the most forlorn, desolate, but also beautiful places in the world, where the wonders of roads have never in all of human history been built. I've tried to cover as many relevant places as I can (and I've certainly covered more than I originally intended to), but of course I couldn't ever cover all of them. As I said, I've avoided discussion of islands, as a general rule, mainly because there is a colossal number of roadless islands around, and the list could go on forever.

I hope you've found this spin around the globe informative. And don't let such a minor inconvenience as a lack of roads stop you from visiting as many of these places as you can! Comments and feedback welcome.

]]>There are plenty of articles round and about the interwebz, aimed more at the practical side of coming to Chile: i.e. tips regarding how to get around; lists of rough prices of goods / services; and crash courses in Chilean Spanish. There are also a number of commentaries on the cultural / social differences between Chile and elsewhere – on the national psyche, and on the political / economic situation.

My endeavour is to avoid this article from falling neatly into either of those categories. That is, I'll be covering some eccentricities of Chile that aren't practical tips as such, although knowing about them may come in handy some day; and I'll be covering some anecdotes that certainly reflect on cultural themes, but that don't pretend to paint the Chilean landscape inside-out, either.

Que disfrutiiy, po.

Image sources: Times Journeys / 2GB.

Fin de mes

Here in Chile, all that is money-related is monthly. You pay everything monthly (your rent, all your bills, all membership fees e.g. gym, school / university fees, health / home / car insurance, etc); and you get paid monthly (if you work here, which I don't). I know that Chile isn't the only country with this modus operandi: I believe it's the European system; and as far as I know, it's the system in various other Latin American countries too.

In Australia – and as far as I know, in most English-speaking countries – there are no set-in-stone rules about the frequency with which you pay things, or with which you get paid. Bills / fees can be weekly, monthly, quarterly, annual… whatever (although rent is generally charged and is talked about as a weekly cost). Your pay cheque can be weekly, fortnightly, monthly, quarterly… equally whatever (although we talk about "how much you earn" annually, even though hardly anyone is paid annually). I guess the "all monthly" system is more consistent, and I guess it makes it easier to calculate and compare costs. However, having grown up with the "whatever" system, "all monthly" seems strange and somewhat amusing to me.

In Chile, although payment due dates can be anytime throughout the month, almost everyone receives their salary at fin de mes (the end of the month). I believe the (rough) rule is: the dosh arrives on the actual last day of the month if it's a regular weekday; or the last regular weekday of the month, if the actual last day is a weekend or public holiday (which is quite often, since Chile has a lot of public holidays – twice as many as Australia!).

This system, combined with the last-minute / impulsive form of living here, has an effect that's amusing, frustrating, and (when you think about it) depressingly predictable. As I like to say (in jest, to the locals): in Chile, it's Christmas time every end-of-month! The shops are packed, the restaurants are overflowing, and the traffic is insane, on the last day and the subsequent few days of each month. For the rest of the month, all is quiet. Especially the week before fin de mes, which is really Struggle Street for Chileans. So extreme is this fin de mes culture, that it's even busy at the petrol stations at this time, because many wait for their pay cheque before going to fill up the tank.

This really surprised me during my first few months in Chile. I used to ask: ¿Qué pasa? ¿Hay algo important hoy? ("What's going on? Is something important happening today?"). To which locals would respond: Es fin de mes! Hoy te pagan! ("It's end-of-month! You get paid today!"). These days, I'm more-or-less getting the hang of the cycle; although I don't think I'll ever really get my head around it. I'm pretty sure that, even if we did all get paid on the same day in Australia (which we don't), we wouldn't all rush straight to the shops in a mad stampede, desperate to spend the lot. But hey, that's how life is around here.

Cuotas

Continuing with the socio-economic theme, and also continuing with the "all-monthly" theme: another Chile-ism that will never cease to amuse and amaze me, is the omnipresent cuotas ("monthly instalments"). Chile has seen a spectacular rise in the use of credit cards, over the last few decades. However, the way these credit cards work is somewhat unique, compared with the usual credit system in Australia and elsewhere.

Any time you make a credit card purchase in Chile, the cashier / shop assistant will, without fail, ask you: ¿cuántas cuotas? ("how many instalments?"). If you're using a foreign credit card, like myself, then you must always answer: sin cuotas ("no instalments"). This is because, even if you wanted to pay for your purchase in chunks over the next 3-24 months (and trust me, you don't), you can't, because this system of "choosing at point of purchase to pay in instalments" only works with local Chilean cards.

Chile's current president, the multi-millionaire Sebastian Piñera, played an important part in bringing the credit card to Chile, during his involvement with the banking industry before entering politics. He's also generally regarded as the inventor of the cuotas system. The ability to choose your monthly instalments at point of sale is now supported by all credit cards, all payment machines, all banks, and all credit-accepting retailers nationwide. The system has even spread to some of Chile's neighbours, including Argentina.

Unfortunately, although it seems like something useful for the consumer, the truth is exactly the opposite: the cuotas system and its offspring, the cuotas national psyche, has resulted in the vast majority of Chileans (particularly the less wealthy among them) being permanently and inescapably mired in debt. What's more, although some of the cuotas offered are interest-free (with the most typical being a no-interest 3-instalment plan), some plans and some cards (most notoriously the "department store bank" cards) charge exhorbitantly high interest, and are riddled with unfair and arcane terms and conditions.

Última hora

Chile's a funny place, because it's so "not Latin America" in certain aspects (e.g. much better infrastructure than most of its neighbours), and yet it's so "spot-on Latin America" in other aspects. The última hora ("last-minute") way of living definitely falls within the latter category.

In Chile, people do not make plans in advance. At least, not for anything social- or family-related. Ask someone in Chile: "what are you doing next weekend?" And their answer will probably be: "I don't know, the weekend hasn't arrived yet… we'll see!" If your friends or family want to get together with you in Chile, don't expect a phone call the week before. Expect a phone call about an hour before.

I'm not just talking about casual meet-ups, either. In Chile, expect to be invited to large birthday parties a few hours before. Expect to know what you're doing for Christmas / New Year a few hours before. And even expect to know if you're going on a trip or not, a few hours before (and if it's a multi-day trip, expect to find a place to stay when you arrive, because Chileans aren't big on making reservations).

This is in stark contrast to Australia, where most people have a calendar to organise their personal life (something extremely uncommon in Chile), and where most peoples' evenings and weekends are booked out at least a week or two in advance. Ask someone in Sydney what their schedule is for the next week. The answer will probably be: "well, I've got yoga tomorrow evening, I'm catching up with Steve for lunch on Wednesday, big party with some old friends on Friday night, beach picnic on Saturday afternoon, and a fancy dress party in the city on Saturday night." Plus, ask them what they're doing in two months' time, and they'll probably already have booked: "6 nights staying in a bungalow near Batemans Bay".

The última hora system is both refreshing and frustrating, for a planned-ahead foreigner like myself. It makes you realise just how regimented, inflexible, and lacking in spontenaeity life can be in your home country. But, then again, it also makes you tear your hair out, when people make zero effort to co-ordinate different events and to avoid clashes. Plus, it makes for many an awkward silence when the folks back home ask the question that everybody asks back home, but that nobody asks around here: "so, what are you doing next weekend?" Depends which way the wind blows.

Sit down

In Chile (and elsewhere nearby, e.g. Argentina), you do not eat or drink while standing. In most bars in Chile, everyone is sitting down. In fact, in general there is little or no "bar" area, in bars around here; it's all tables and chairs. If there are no tables or chairs left, people will go to a different bar, or wait for seats to become vacant before eating / drinking. Same applies in the home, in the park, in the garden, or elsewhere: nobody eats or drinks standing up. Not even beer. Not even nuts. Not even potato chips.

In Australia (and in most other English-speaking countries, as far as I know), most people eat and drink while standing, in a range of different contexts. If you're in a crowded bar or pub, eating / drinking / talking while standing is considered normal. Likewise for a big house party. Same deal if you're in the park and you don't want to sit on the grass. I know it's only a little thing; but it's one of those little things that you only realise is different in other cultures, after you've lived somewhere else.

It's also fairly common to see someone eating their take-away or other food while walking, in Australia. Perhaps some hot chips while ambling along the beach. Perhaps a sandwich for lunch while running (late) to a meeting. Or perhaps some lollies on the way to the bus stop. All stuff you wouldn't blink twice at back in Oz. In Chile, that is simply not done. Doesn't matter if you're in a hurry. It couldn't possibly be such a hurry, that you can't sit down to eat in a civilised fashion. The Chilean system is probably better for your digestion! And they have a point: perhaps the solution isn't to save time by eating and walking, but simply to be in less of a hurry?

Image source: Dondequieroir.

Walled and shuttered

One of the most striking visual differences between the Santiago and Sydney streetscapes, in my opinion, is that walled-up and shuttered-up buildings are far more prevalent in the former than in the latter. Santiago is not a dangerous city, by Latin-American or even by most Western standards; however, it often feels much less secure than it should, particularly at night, because often all you can see around you is chains, padlocks, and sturdy grilles. Chileans tend to shut up shop Fort Knox-style.

Walk down Santiago's Ahumada shopping strip in the evening, and none of the shopfronts can be seen. No glass, no lit-up signs, no posters. Just grey steel shutters. Walk down Sydney's Pitt St in the evening, and – even though all the shops close earlier than in Santiago – it doesn't feel like a prison, it just feels like a shopping area after-hours.

In Chile, virtually all houses and apartment buildings are walled and gated. Also, particularly ugly in my opinion, schools in Chile are surrounded by high thick walls. For both houses and schools, it doesn't matter if they're upper- or lower-class, nor what part of town they're in: that's just the way they build them around here. In Australia, on the other hand, you can see most houses and gardens from the street as you go past (and walled-in houses are criticised as being owned by "paranoid people"); same with schools, which tend to be open and abundant spaces, seldom delimiting their boundary with anything more than a low mesh fence.

As I said, Santiago isn't a particularly dangerous city, although it's true that robbery is far more common here than in Sydney. The real difference, in my opinion, is that Chileans simply don't feel safe unless they're walled in and shuttered up. Plus, it's something of a vicious cycle: if everyone else in the city has a wall around their house, and you don't, then chances are that your house will be targeted, not because it's actually easier to break into than the house next door (which has a wall that can be easily jumped over anyway), but simply because it looks more exposed. Anyway, I will continue to argue to Chileans that their country (and the world in general) would be better with less walls and less barriers; and, no doubt, they will continue to stare back at me in bewilderment.

Image source: eszsara (Flickriver).

In summary

So, there you have it: a few of my random observations about life in Santiago, Chile. I hope you've found them educational and entertaining. Overall, I've enjoyed my time in this city; and while I'm sometimes critical of and poke fun at Santiago's (and Chile's) peculiarities, I'm also pretty sure I'll miss then when I'm gone. If you have any conclusions of your own regarding life in this big city, feel free to share them below.

]]>Rhodes's dream remains unfulfilled to this day.

"The Rhodes Colossus" illustration originally from Punch magazine, Vol. 103, 10 Dec 1892; image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Africa satellite image courtesy of Google Earth.

Nevertheless, significant additions have been made to Africa's rail network during the interluding century; and, in fact, only a surprisingly small section of the Cape to Cairo route remains bereft of the Iron Horse's footprint.

Although both information about – (a) the historical Cape to Cairo dream; and (b) the history / current state of the route's various railway segments – abound, I was unable to find any comprehensive study of the current state of the railway in its entirety.

This article, therefore, is an endeavour to examine the current state of the full Cape to Cairo Railway. As part of this study, I've prepared a detailed map of the route, which marks in-service sections, abandoned sections, and missing sections. The map has been generated from a series of KML files, which I've made publicly available on GitHub, and for which I welcome contributions in the form of corrections / tweaks to the route.

Southern section

As its name suggests, the line begins in Cape Town, South Africa. The southern section of the railway encompasses South Africa itself, along with the nearby countries that have historically been part of the South African sphere of influence: that is, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Zambia.

The first segment – Cape Town to Johannesburg – is also the oldest, the best-maintained, and the best-serviced part of the entire route. The first train travelled this segment in 1892. There has been continuous service ever since. It's the only train route in all of Africa that can honestly claim to provide a "European standard" of passenger service, between the two major cities that it links. That is, there are numerous classes of service operating on the line – ranging from basic inter-city commuter trains, to business-style fast trains, to luxury sleeper trains – running several times a day.

So, the first leg of the railway is the one that we should be least worried about. Hence, it's marked in green on the map. This should come as no surprise, considering that South Africa has the best-developed infrastructure in all of Africa (by a long shot), as well as Africa's largest economy.

After Johannesburg, we continue along the railway that was already fulfilling Cecil Rhodes's dream before his death. This segment runs through modern-day Botswana, which was previously known as Bechuanaland Protectorate. From Johannesburg, it connects to the city of Mafeking, which was the capital of the former Bechuanaland Protectorate, but which today is within South Africa (where it is a regional capital). The line then crosses the border into Botswana, passes through the capital Gaborone, and continues to the city of Francistown in Botswana's north-east.

Unfortunately, since the opening of the Beitbridge Bulawayo Railway in Zimbabwe in 1999 (providing a direct train route between Zimbabwe and South Africa for the first time), virtually all regular passenger service on this segment (and hence, virtually all regular passenger service on Botswana's train network) has been cancelled. The track is still being maintained, and (apart from some freight trains) there are still occasional luxury tourist trains using the route. However, it's unclear if there are still any regular passenger services between Johannesburg and Mafeking (if there are, they're very few); and sources indicate that there are no regular passenger services at all between Mafeking and Francistown. Hence, the segment is marked in yellow on the map.

(I should also note that the new direct train route from South Africa to Zimbabwe, does actually provide regular passenger service, from Johannesburg to Messina, and then from Beitbridge to Bulawayo, with service missing only in the short border crossing between Messina and Beitbridge. However, I still consider the segment via Botswana to be part of the definitive "Cape to Cairo" route: because of its historical importance; and because only quite recently has service ceased on this segment and has an alternative segment been open.)

From Francistown onwards, the situation is back in the green. There is a passenger train from Francistown to Bulawayo, that runs three times a week. I should also mention here, that Bulawayo is quite a significant spot on the Cape to Cairo Railway, as (a) the grave of Cecil Rhodes can be found atop "World's View", a panoramic hilltop in nearby Matobo National Park; and (b) Bulawayo was the first city that the railway reached in (former) Rhodesia, and to this day it remains Zimbabwe's rail hub. Bulawayo is also home to a railway museum.

For the remainder of the route through Zimbabwe, the line remains in the green. There's a daily passenger service from Bulawayo to Victoria Falls. Sadly, this spectacular leg of the route has lost much of its former glory: due to Zimbabwe's recent economic and political woes, the trains are apparently looking somewhat the worse for wear. Nevertheless, the service continues to be popular and reasonably reliable.

The green is briefly interrupted by a patch of yellow, at the border crossing between Zimbabwe and Zambia. This is because there has been no passenger service over the famous Victoria Falls Bridge – which crosses the Zambezi River at spraying distance from the colossal waterfall, connecting the towns of Victoria Falls and Livingstone – more-or-less since the 1970s. Unless you're on board one of the infrequent luxury tourist trains that still traverse the bridge, it must be crossed on foot (or using local transport). It should also be noted that although the bridge is still most definitely intact and looking solid, it's more than 100 years old, and experts have questioned whether it's receiving adequate care and maintenance.

Image sourced from: Car Hire Victoria Falls.

Once in Zambia – formerly known as Northern Rhodesia – regular passenger services continue north to the capital, Lusaka; and from there, onward to the crossroads town of Kapiri Mposhi. It's here that the southern portion of the modern-day Cape to Cairo railway ends, since Kapiri Mposhi is the meeting-point of the colonial-era, British-built, South-African / Rhodesian railway network, and a modern-era East-African rail link that was unanticipated in Rhodes's plan.

I should also mention here that the colonial-era network continues north from Kapiri Mposhi, crossing the border with modern-day DR Congo (formerly known as the Belgian Congo), and continuing up to the shores of Lake Tanganyika, where it terminates at the town of Kalemie. The plan in the colonial era was that the Cape to Cairo passenger link would continue north via the Great Lakes in this region of Africa – in the form of lake / river ferries, up to Lake Albert, on the present-day DR Congo / Ugandan border – after which the rail link would resume, up to Egypt via Sudan.

However, I don't consider this segment to be part of the definitive "Cape to Cairo" route, because: (a) further rail links between the Great Lakes, up to Lake Albert, were never built; (b) the line running through eastern DR Congo, from the Zambian border to Kalemie on Lake Tanganyika, is apparently in serious disrepair; and (c) an alternative continuous rail link has existed, since the 1970s, via East Africa, and the point where this link terminates in modern-day Uganda is north of Lake Albert anyway. Therefore, the DR Congo – Great Lakes segment is only being mentioned here as an anecdote of history; and we now turn our attention to the East African network.

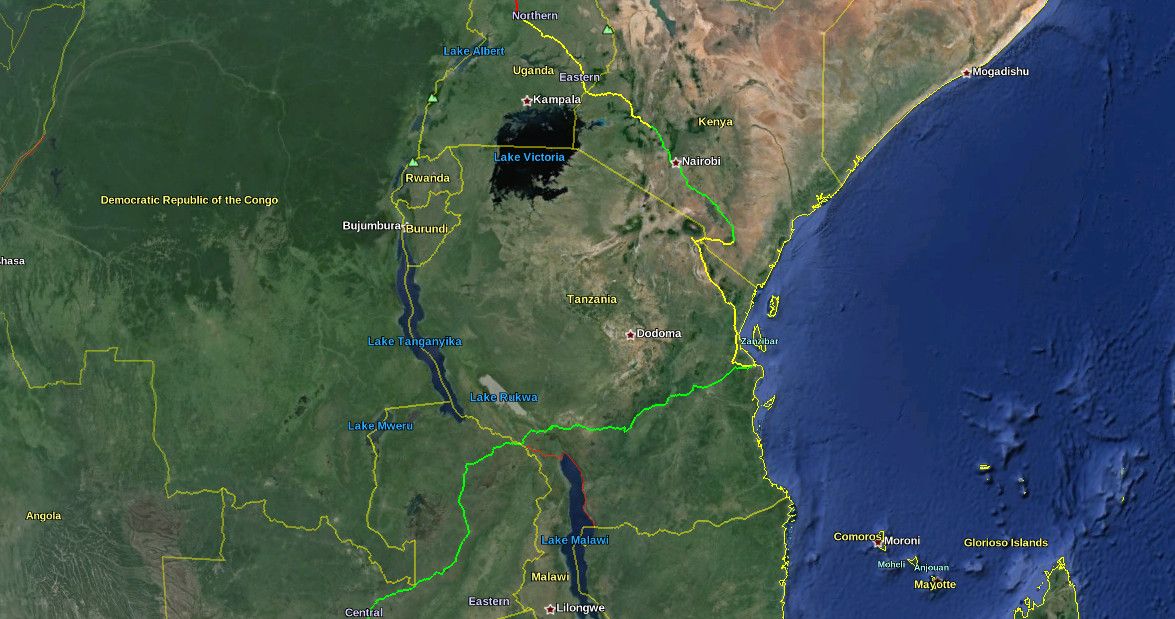

Eastern section

The Eastern section of the railway is centred in modern-day Tanzania and Kenya, although it begins and ends within the inland neighbours of these two coastal nations – Zambia and Uganda, respectively. This region, much like Southern Africa, was predominantly ruled under British colonialism in the 19th century (which is why Kenya, the region's hub, was formerly known as British East Africa). However, modern-day Tanzania (formerly called Tanganyika, before the union of Tanganyika with Zanzibar) was originally German East Africa, before becoming a British protectorate in the 20th century.

Kapiri Mposhi, in Zambia, is the start of the TAZARA Railway; this railway runs through the north-east of Zambia, crosses the border to Tanzania near Mbeya, and finishes on the Indian Ocean coast at Dar es Salaam, Tanzania's largest city.

The TAZARA is the newest link in the Cape to Cairo railway network: it was built and financed by the Chinese, and was opened in 1976. It's the only line in the network – and one of the only railway lines in all of Africa – that was built (a) by non-Europeans; and (b) in the post-colonial era. It was not envisioned by Rhodes (nor by his contemporaries), who wanted the line to pass through wholly British-controlled territory (Tanzania was still German East Africa in Rhodes's era). The Zambians wanted it, in order to alleviate their dependence (for international transport) on their southern neighbours Rhodesia and South Africa, with whom tensions were high in the 1970s, due to those nations' Apartheid governments. The line has been in regular operation since opening; hence, it's marked in green on the map.

Image source: Mzuzu Transit.

Although the TAZARA line doesn't quite touch the other Tanzanian railway lines that meet in Dar es Salaam, I haven't marked any gap in the route at Dar es Salaam. This is for two reasons. Firstly, from what I can tell (by looking at maps and satellite imagery), the terminus of the TAZARA in Dar es Salaam is physically separated from the other lines, by a distance of less than two blocks, i.e. a negligible amount. Secondly, the TAZARA is (as of 1998) physically connected to the other Tanzanian railway lines, at a junction near the town of Kidatu, and there is a cargo transshipment facility at this location. However, I don't believe there's any passenger service from Kidatu to the rest of the Tanzanian network (only cargo trains). So, the Kidatu connection is being mentioned here only as an anecdote; in my opinion, the definitive "Cape to Cairo" route passes through, and connects at, Dar es Salaam.

From Dar es Salaam, the line north is part of the decaying colonial-era Tanzanian rail network. This line extends up to the city of Arusha; the part that we're interested in ends at Moshi (east of Arusha), from where another line branches off, crossing the border into Kenya. Sadly, there has been no regular passenger service on the Arusha line for many years; therefore, nor is there any service to Moshi.

After crossing the Kenyan border, the route passes through the town of Taveta, before continuing on to Voi; here, there is a junction with the most important train line in Kenya: that which connects Mombasa and Nairobi. As with the Arusha line, the Moshi – Voi line has also been bereft of regular passenger service for many years. This entire portion of the rail network appears to be in a serious state of neglect. If there are any trains running in this area, they would be occasional freight trains; and if any track maintenance is being performed on these lines, it would be the bare minimum. Therefore, the full segment from Dar es Salaam to Voi is marked in yellow on the map.

From Voi, there are regular passenger services on the main Kenyan rail line to Nairobi; and onward from Nairobi, there are further passenger services (which appear to be less reliable, but regular nonetheless) to the city of Kisumu, which borders Lake Victoria. The part of this route that we're interested in ends at Nakuru (about halfway between Nairobi and Kisumu), from where another line branches off towards Uganda. The route through Kenya, from Voi to Nakuru, is therefore in the green.

After Nakuru, the line meanders its way towards the Ugandan border; and at Tororo (a city on the Ugandan side), it connects with the Ugandan network. There is apparently no longer any passenger service available from Nakuru to Tororo – i.e. there is no service between Kenya and Uganda. As such, this segment is marked in yellow.

The once-proud Ugandan railway network today lies largely abandoned, a victim of Uganda's tragic history of dictatorship, bloodshed and economic disaster since the 1970s. The only inter-city line that maintains regular passenger service, is the main line from the capital, Kampala, to Tororo. As this line terminates at Kampala, on the shores of Lake Victoria (like the Kenyan line to Kisumu), it is of little interest to us.

From Tororo, Uganda's northern railway line stretches north and then west across the country in a grand arc, before terminating at Pakwach, the point where the Albert Nile river begins, adjacent to Lake Albert. (This line supposedly once continued from Pakwach to Arua; however, I haven't been able to find this extension marked on any maps, nor visible in any satellite imagery). The northernmost point of this railway line is at Gulu; and so, it is the segment of the line up to Gulu that interests us.

Sadly, the entire segment from Tororo to Gulu appears to be abandoned; whether there is even freight service today seems doubtful; thus, this segment is marked in yellow. And, doubly sad, Gulu is also the point at which a continuous, uninterrupted rail network all the way from Cape Town, comes to its present-day end. No rail line was ever constructed north of Gulu in Uganda. Therefore, it is at Gulu that the East African portion of the Cape to Cairo Railway bids us farewell.

Northern section

The northern section of the railway is mainly within Sudan and Egypt – although we'll be tracking (the missing section of) the route from northern Uganda; and, since 2011, the route also passes through the newly-independent South Sudan. As with its southern and eastern African counterparts, the northern part of the railway was primarily built by the British, during their former colonial rule in the region.

We pick up from where we finished in the previous section: Gulu in northern Uganda. As has already been mentioned: from Gulu, we hit the first (of only two) – and the most significant – of the missing links in the Cape to Cairo Railway. The next point where the railway begins again, is the city of Wau, located in north-western South Sudan. Therefore, this segment of the route is marked in red on the map. In the interests of at least marking some form of transport along the missing link, the red line follows the main highway route through the region: the Ugandan A104 highway from Gulu north to the border; and from there, at the city of Nimule (just over the border in South Sudan), the South Sudanese A43 highway to Juba (the capital), and then on to Wau (this highway route is about 1,000km in total).

There has been no shortage of discussion, both past and present, regarding plans to bridge this important gap in the rail network. There have even been recent official announcements by the governments of Uganda and of South Sudan, declaring their intention to build a new rail segment from Gulu to Wau. However, there hasn't been any concrete action since the present-day railheads were established about 50 years ago; and, considering that northern Uganda / South Sudan is one of the most troubled regions in the world today, I wouldn't hold my breath waiting for any fresh steel to appear on the ground (not to mention waiting for repairs of the existing neglected / war-damaged train lines). The folks over there have plenty of other, more urgent matters to attend to.

Wau is the southern terminus of the Sudanese rail network. From Wau, the line heads more-or-less straight up, crossing the border from South Sudan into Sudan, and joining the Khartoum – Darfur line at Babanusa. The Babanusa – Wau line was one of the last train lines to be completed in Sudan, opening in 1962 (around the same time as the Tororo – Gulu – Pakwach line opened in neighbouring Uganda). I found a colourful account of a passenger journey along this line, from around 2000. As I understand it, shortly after this time, the line was damaged by mines and explosives, a victim of the civil war. The line is supposedly rehabilitated, and passenger service has ostensibly resumed – however, personally I'm not convinced that this is the case. Therefore, this segment is marked in yellow on the map.

Similarly, the remaining segment of rail onwards to the capital – Babanusa to Khartoum – was apparently damaged during the civil war (that's on top of the line's ageing and dismally-maintained state). There are supposedly efforts underway to rehabilitate this line (along with the rest of the Sudanese rail network in general), and to restore regular services along it. I haven't been able to confirm whether passenger services have yet been restored; therefore, this segment is also marked in yellow on the map.

From the Sudanese capital Khartoum, the country's principal train line traverses the rest of the route north, running along the banks of the Upper Nile for about half the route, before making a beeline across the harsh expanse of the Nubian Desert, and terminating just before the Egyptian border at the town of Wadi Halfa, on the shores of Lake Nasser (the Sudanese side of which is called Lake Nubia). Although trains do appear to get suspended for long-ish intervals, this is the best-maintained route in war-ravaged Sudan, and it appears that regular passenger services are operating from Khartoum to Wadi Halfa. Therefore, this segment is marked in green on the map.

The border crossing from Sudan into Egypt is the second of the two missing links in the Cape to Cairo Railway. In fact, there isn't even a road connecting the two nations, at least not anywhere near the Nile / Lake Nasser. However, this missing link is of less concern, because: (a) the distance is much less (approximately 350km); and (b) Lake Nasser is a large and easily navigable body of water, with regular ferry services connecting Wadi Halfa in Sudan with Aswan in Egypt. Indeed, the convenience and the efficiency of the ferry service (along with the cargo services operating on the lake) is the very reason why nobody's ever bothered to build a rail link through this segment. So, this segment is marked in red on the map: the red line more-or-less follows the ferry route over the lake.

Aswan is Egypt's southernmost city; this has been the case for millenia, since it was the southern frontier of the realm of the Pharoahs, stretching back to ancient times. Aswan is also the southern terminus of the Egyptian rail network's main line; from here, the line snakes its way north, tracing the curves of the heavily-populated Nile River valley, all the way to Cairo, after which the vast Nile Delta begins.

Image source: About.com: Cruises.

The Aswan – Cairo line – the very last segment of Rhodes's grand envisioned network – is second only to the network's very first segment (Cape Town – Johannesburg) in terms of service offerings. There are a range of passenger services available, ranging from basic economy trains, to luxury tourist-oriented sleeper coaches, traversing the route daily. Although Egypt is currently in the midst of quite dramatic political turmoil (indeed, Egypt's recent military coup and ongoing protests are front-page news as I write this), as far as I know these issues haven't seriously disrupted the nation's train services. Therefore, this segment is marked in green on the map.

I should also note that after Cairo, Egypt's main rail line continues on to Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast. However, of course, the Cairo – Alexandria segment is not marked on the map, because it's a map of the Cape to Cairo railway, not the Cape to Alexandria railway! Also, Cairo could be considered to be "virtually" on the Mediterranean coast anyway, as it's connected by various offshoots of the Nile (in the Nile Delta) to the Mediterranean, with regular maritime traffic along these waterways.

End of the line

Well, there you have it: a thorough exercise in mapping and in narrating the present-day path of the Cape to Cairo Railway.

Personally, I've never been to Africa, let alone travelled any part of this long and diverse route. I'd love to do so, one day: although as I've described above, many parts of the route are currently quite a challenge to travel through, and will probably remain so for the foreseeable future. Naturally, I'd be delighted if anyone who has travelled any part of the route could share their "war stories" as comments here.

One question that I've asked myself many times, while researching and writing this article, is: in what year was the Cape to Cairo Railway at its best? (I.e. in what year was more of the line "green" than in any other year?). It would seem that the answer is probably 1976. This year was certainly not without its problems; but, at least as far as the Cape to Cairo endeavour goes, I believe that it was "as good as it's ever been".

This was the year that the TAZARA opened (which is to this day the "latest piece in the puzzle"), providing its inaugural Zambia – Tanzania service. It was one year before the 1977 dissolution of the East African Railways and Harbours Corporation, which jointly developed and managed the railways of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania (EAR&H's peak was probably in 1962, it was already in serious decline by 1976, but nevertheless it continued to provide comprehensive services until its end). And it was a year when Sudan's railways were in better operating condition, that nation being significantly less war-damaged than it is today (although Sudan had already suffered several years of civil war by then).

Unfortunately, it was also a year in which the Rhodesian Bush War was raging intensely – as such, on account of the hostilities between then-Rhodesia and Zambia, the Victoria Falls Bridge was largely closed to all traffic at that time (and, indeed, all travel within then-Rhodesia was probably quite difficult at that time). Then again, this hostility was also the main impetus for the construction of the TAZARA link; so, in the long-term, the tensions in then-Rhodesia actually improved the rail network more than they hampered it.

Additionally, it was a year in which Idi Amin's brutal reign of terror in Uganda was at its height. At that time, travel within Uganda was extremely dangerous, and infrastructure was being destroyed more commonly than it was being maintained.

I'm not the first person to make the observation – a fairly obvious one, after studying the route and its history – that travelling from Cape Town to Cairo overland (by train and/or by other transportation) never has been, and to this day is not, an easy expedition! There are numerous change-overs required, including change of railway guage, change to land vehicle, change to maritime vehicle, and more. The majority of the rail (and other) services along the route are poorly-maintained, prone to breakdowns, almost guaranteed to suffer extensive delays / cancellations, and vulnerable to seasonal weather fluctuations. And – as if all those "regular" hurdles weren't enough – many (perhaps the majority) of the regions through which the route passes are currently, or have in recent history been, unstable and dangerous trouble zones.

Hope you enjoyed my run-down (or should I say run-up?) of the Cape to Cairo Railway. Note that – as well as the KML files, which can be opened in Google Earth for best viewing of the route – the route is available here as a Google map.

Your contribution to the information presented here would be most welcome. If you have experience with path editing / Google Earth / KML (added bonus if you're Git / GitHub savvy, and know how to send pull requests), check out the route KML on GitHub, and feel free to refine it. Otherwise, feel free to post your route corrections, your African railway anecdotes, and all your most scathing criticism, using the comment form below (or contact me directly).

]]>Recently, I was looking for a list of all the official crossings between the two countries. Finding such a list, in clear and authoritative form, proved more difficult than I expected. Hence, one thing led to another; and before I knew it, I'd embarked upon a serious research mission to develop such a list myself. So, here it is — a list of all highway border crossings between Chile and Argentina, that are open to the general public.

Note: there's a legend at the end of the article.

Northern crossings

The northern part of the Chile-Argentina frontier is generally hot, dry, and slightly flatter at the top. I found the frontier's northern crossings to be the best-documented, and hence the easiest to research. They're also generally the easiest crossings to make, as they pose the least risk of being impassable due to snowstorms.

Of the northern crossings, the only one I've travelled on is Paso Jama; although I didn't go through the pass itself, I crossed into Chile from Laguna Verde in Bolivia, and cut into the Chilean part of the highway from there (as part of a 4WD tour of the Salar de Uyuni).

Chilean regions: II (Antofagasta), III (Atacama).

Argentine provinces: Jujuy, Salta, Catamarca, La Rioja.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Jama | S.P. de Atacama - S.S. de Jujuy | Main highway | |

| Paso Sico | Antofagasta - Salta | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Socompa | Antofagasta - Salta | Minor highway | |

| Paso San Francisco | Copiacó - S.F.V. de Catamarca | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Pircas Negras | Copiacó - La Rioja | Minor highway |

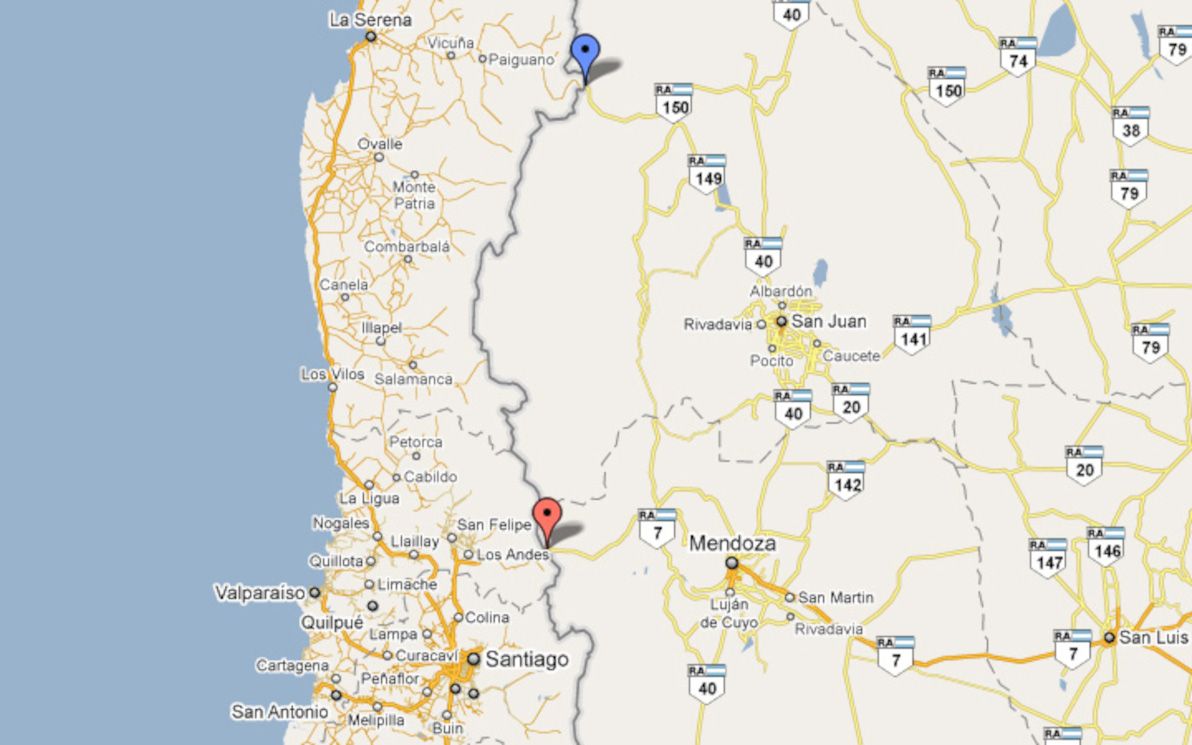

Central crossings

The Central part of the frontier is the most frequently crossed, as it's where you'll find the most direct route from Santiago to Buenos Aires. Unfortunately, Paso Los Libertadores is the only high-quality road in this entire section of the frontier — the mountains are particularly high, and construction of passes is particularly challenging, around here. After all, Aconcagua (the highest mountain in all the Americas) can be clearly seen right next to the main road.

As such, Los Libertadores is an extremely busy pass year-round; this is exacerbated by snowstorms forcing the pass to close during the height of winter, and also occasionally even in summer (despite there being a tunnel under the highest point of the route). I've travelled Los Libertadores twice (once in each direction), and it's a route with beautiful scenery; the zig-zags down the precipitous Chilean side of the pass are also quite hair-raising.

Chilean regions: IV (Coquimbo), V (Valparaíso).

Argentine provinces: San Juan, Mendoza.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Agua Negra | La Serena - San Juan | Minor highway | |

| Paso Los Libertadores | Santiago - Mendoza | Main highway |

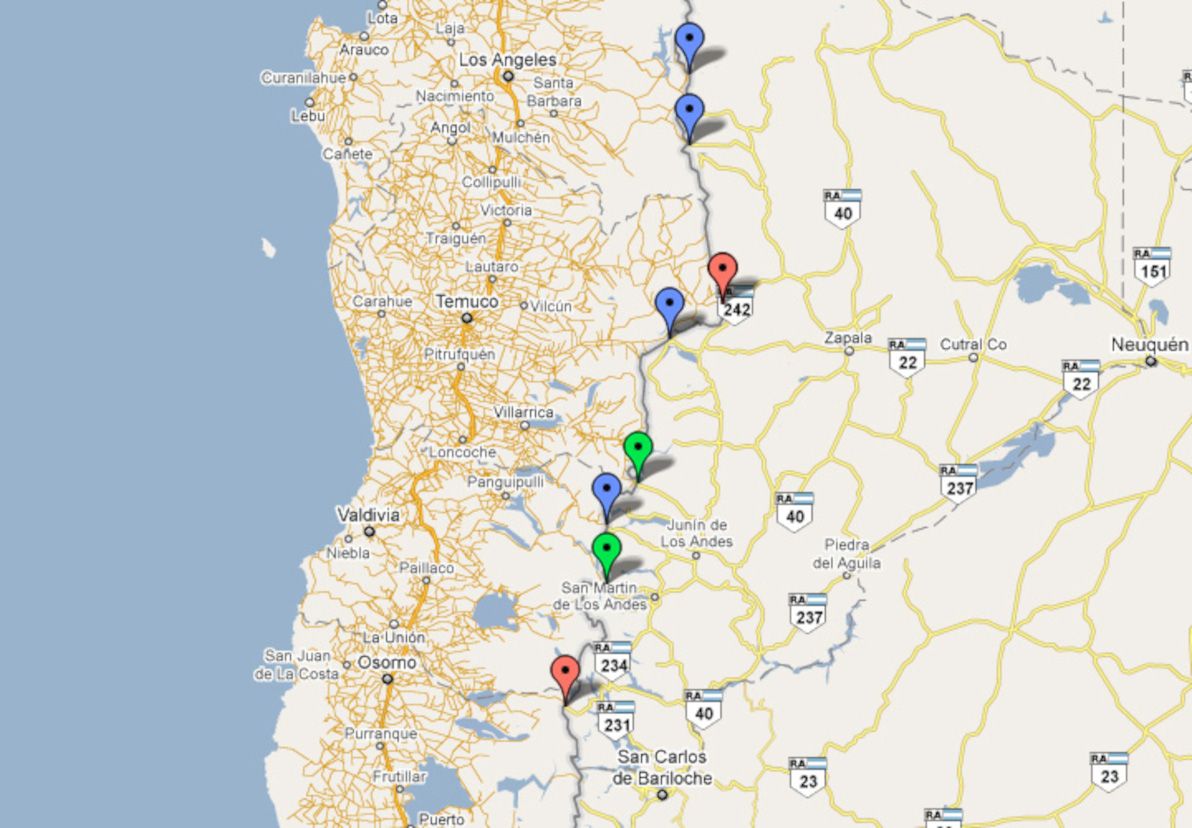

Lake district crossings

The lake districts of both Chile and Argentina are famed for their "Swiss Alps of the South" picturesque beauty, and the border crossings in this area are among the most spectacular of all vistas that the region has to offer. There are numerous border crossings in this area, most of which are quite good roads, and two of which are highway-grade.

Paso Cardenal Antonio Samoré is the only one down here that I've crossed. The roads here are all liable to close due to snow conditions; although I was lucky enough to cross in September with no problems.

I should also note that I've explicitly excluded the famous and beautiful Paso Pérez Rosales (Puerto Montt - S.C. de Bariloche) from the list here: this is because, although it's a paved highway-grade road the whole way, the highway is interrupted by a (long) lake crossing. I'm only including on this list crossings that can be made in one complete, uninterrupted land vehicle journey.

Chilean regions: VIII (Biobío), IX (Araucanía), XIV (Los Ríos).

Argentine provinces: Neuquén.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Pichachén | Los Angeles - Zapala | Minor highway | |

| Paso Copahue | Los Angeles - Zapala | Minor highway | |

| Paso Pino Hachado | Temuco - Neuquén | Main highway | |

| Paso Icalma | Temuco - Neuquén | Minor highway | |

| Paso Mamuil Malal | Pucón - Junín de L.A. | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Carirriñe | Coñaripe - Junin de L.A. | Minor highway | |

| Paso Huahum | Panguipulli - S.M. de Los Andes | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Cardenal Antonio Samoré | Osorno - S.C. de Bariloche | Main highway |

Southern crossings

These are the passes of the barren, empty pampas of Southern Patagonia. There are no main roads around here, and in some cases there are barely any towns for the roads to connect to, either. I haven't personally travelled any of these crossings, nor have I visited this part of Chile or Argentina at all.

Some of these highways go through rivers, with satellite imagery showing no bridges connecting the two sides; I can only assume that the rivers are passable in 4WD, assuming the water levels are low, or assuming the rivers are partly frozen. This was also by far the most difficult region to research: information about these passes is scarce and undetailed.

Chilean regions: X (Los Lagos), XI (Aisén).

Argentine provinces: Chubut, Santa Cruz.

| Name | Route | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Paso Futaleufu | Futaleufu - Esquel | Secondary highway |

| Paso Río Encuentro | Palena - Esquel | Minor highway |

| Paso Las Pampas | Cisnes - Esquel | Minor highway |

| Paso Río Frias | Cisnes - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Pampa Alta | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Coyhaique | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Triana | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Huemules | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Secondary highway |

| Paso Ingeniero Ibáñez-Pallavicini | Puerto Ibáñez - Perito Moreno | Minor highway |

| Paso Río Jeinemeni | Puerto Guadal - Perito Moreno | Minor highway |

| Paso Roballos | Cochrane - Bajo Caracoles | Minor highway |

| Paso Rio Mayer Ribera Norte | O'Higgins - Las Horquetas | Minor highway |

| Paso Rio Mosco | O'Higgins - Las Horquetas | Minor highway |

Extreme south crossings

The passes of the extreme south are easily crossed when weather conditions are good, as the mountains are much lower down here (or are basically plateaus). In winter, however, land transport is seldom an option. There is one main road in the extreme south, connecting Punta Arenas and Rio Gallegos.

The only crossing I've made in the extreme south is through Paso Rio Don Guillermo, which is unsealed and is little more than a cattle track (although it's pretty straight and flat). The buses from Puerto Natales to El Calafate use this pass: the entrance to the road has a chain across it on both ends, which is unlocked by border police to let the buses through.

Chilean regions: XII (Magallanes).

Argentine provinces: Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Rio Don Guillermo | Puerto Natales - El Calafate | Minor highway | |

| Paso Dorotea | Puerto Natales - Rio Gallegos | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Laurita - Casas Vieja | Puerto Natales - Rio Gallegos | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Integración Austral | Punta Arenas - Río Gallegos | Main highway | |

| Paso San Sebastián | Porvenir - Rio Grande | Secondary highway |

Legend

Note: here's a link to the Google Map of Chile - Argentina border crossings that is referenced throughout this article.

Main highway

- Red markers on map

- Fully paved

- Public bus services

- Open almost year-round

- Customs and immigration integrated into the crossing

- Constant traffic

Secondary highway

- Green markers on map

- Partially paved

- Little or no public bus services

- Possibly closed some or most of the year

- Customs and immigration possibly integrated into the crossing

- Lesser or seasonal traffic

Minor highway

- Blue markers on map

- Unpaved

- No public bus services, and/or only open for authorised vehicles

- Not open year-round

- Customs and immigration must be done before and/or after the crossing

- Little or no traffic

Additional references

- Chilean government's list of permanent border crossings

- Wikipedia's list of all Argentine border crossings

- Wikipedia's list of countries and territories by land borders

- Viva travel guides: lakes district border crossings

- Neuquén tourism's border crossings list

- Look Patagonia's list of border crossings in Argentine Neuquén province

- Look Patagonia's list of border crossings in Argentine Chubut province

- Interpatagonia's list of passes that lead to Coyhaique

One other thing, though. It's also never been easier to inadvertently take it all for granted. To forget that just one generation ago, there were no budget intercontinental flights, no phrasebooks, no package tours, no visa-free agreements. And, of course, snail mail and telegrams were a far cry from our beloved modern Internet.

But that's not all. The global travel that many of us enjoy today, is only possible thanks to a dizzying combination of fortunate circumstances. And this tower (no less) of circumstances is far from stable. On the contrary: it's rocking to and fro like a pirate ship on crack. I know it's hard for us to comprehend, let alone be constantly aware of, but it wasn't like this all that long ago, and it simply cannot last like this much longer. We are currently living in a window of opportunity like none ever before. So, carpe diem — seize the day!

Have you ever before thought about all the things that make our modern globetrotting lives possible? (Of course, when I say "us", I'm actually referring to middle- or upper-class citizens of Western countries, a highly privileged minority of the world at large). And have you considered that if just one of these things were to swing suddenly in the wrong direction, our opportunities would be slashed overnight? Scary thought, but undeniably true. Let's examine things in more detail.

International relations

In general, these are at an all-time global high. Most countries in the world currently hold official diplomatic relations with each other. There are currently visa-free arrangements (or very accessible tourist visas) between most Western countries, and also between Western countries and many developing countries (although seldom vice versa, a glaring inequality). It's currently possible for a Western citizen to temporarily visit virtually every country in the world; although for various developing countries, some bureaucracy wading may be involved.

International relations is the easiest thing for us to take for granted, and it's also the thing that could most easily and most rapidly change. Let's assume that tomorrow, half of Asia and half of Africa decided to deny all entry to all Australians, Americans, and Europeans. It could happen! It's the sovereign right of any nation, to decide who may or may not enter their soil. And if half the governments of the world decide — on the spur of the moment — to bar entry to all foreigners, there's absolutely nothing that you or I can do about it.

Armed conflict

This is (of course) always a problem in various parts of the world. Parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America are currently unsafe due to armed conflict, mainly from guerillas and paramilitary groups (although traditional war between nations still exists today as well). Armed conflict is relatively contained within pockets of the globe right now.

But that could very easily change. World War III could erupt tomorrow. Military activity could commence in parts of the world that have been boring and peaceful for decades, if not centuries. Also, in particular, most hostility in the world today is currently directed towards other local groups; that hostility could instead be directed at foreigners, including tourists.

War between nations is also the most likely cause for a breakdown in international relations worldwide (it's not actually very likely that they'd break down for no reason — although a global spout of insane dictators is not out of the question). This form of conflict is currently very confined. But if history is any guide, then that is an extremely uncommon situation that cannot and will not last.

Infectious diseases

This is also a problem that has never gone away. However, it's currently relatively safe for tourists to travel to almost everywhere in the world, assuming that proper precautions are taken. Most infectious diseases can be defended against with vaccines. AIDS and other STDs can be controlled with safe and hygienic sexual activity. Water-borne sicknesses such as giardia, and mosquito-borne sicknesses such as malaria, can be defended against with access to bottled water and repellents.

Things could get much worse. We've already seen, with recent scares such as Swine Flu, how easily large parts of the world can become off-limits due to air-borne diseases for which there is no effective defence. In the end, it turned out that Swine Flu was indeed little more than a scare (or an epidemic well-handled; perhaps more a matter of opinion than of fact). If an infectious disease were contagious enough and aggressive enough, we could see entire continents being indefinitely declared quarantine zones. That could put a dent in some people's travel plans!

Environmental contamination

There are already large areas of the world that are effectively best avoided, due to some form of serious environmental contamination. But today's picture is merely the tip of the iceberg. If none of the other factors get worse, then I guarantee that this is one factor that will. It's happening as we speak.

Air pollution is already extreme in many of the world's major cities and industrial areas, particularly in Asia. However, serious though it is, large populations are managing to survive in areas where it's very high. Water contamination is a different story. If an entire country, or even an entire region, has absolutely no potable water, then living and travelling in those areas becomes quite hard.

Of course, the most serious form of environmental contamination possible, is a nuclear disaster. Unfortanately, the potential for nuclear catastrophe is still positively massive. Nuclear disarmament has been a slow and limited process. And weapons aside, nuclear reactors are still abundant in much of the world. A Chernobyl-like event on a scale 100 times bigger — that could sure as hell put travel plans to entire continents on hold indefinitely.

Flights