There are many aspects of code that you can care about. Formatting. Modularity. Meaningful naming. Performance. Security. Test coverage. And many more. Even if you care about just one of these, then: (a) I salute you, for you are a good dev; and (b) that means that you're passionate about code, which in turn means that you'll care about more aspects of code as you grow and mature, which in turn means that you'll develop more of them there skills, as a natural side effect. The fact that you care, however, is the foundation of it all.

Image source: TripAdvisor

If you care about code, then code isn't just a means to an end: it's an end unto itself. If you truly don't care about code at all, but only what it accomplishes, then not only are you not a good dev, you're not really a dev at all. Which is OK, not everyone has to be a dev. If what you actually care about is that the "Unfranked Income YTD" value is accurate, then you're probably a (good) accountant. If it's that the sidebar is teal, then you're probably a (good) graphic designer. If it's that national parks are distinguishable from state forests at most zoom levels, then you're probably a (good) cartographer. However, if you copy-pasted and cobbled together snippets of code to reach your goal, without properly reading or understanding or caring about the content, then I'm sorry, but you're not a (good) dev.

Of course, a good dev needs at least some "hard" skills too. But, as anyone who has ever interviewed or worked with a dev knows, those skills – listed so prominently on CVs and in JDs – are pretty worthless if there's no quality included. Great, 10 years of C++ experience! And you've always given all variables one-character names? Great, you know Postgres! But you never add an index until lots of users complain that a page is slow? Great, a Python ninja! What's that, you just write one test per piece of functionality, and it's a Selenium test? Call me harsh, but those sound to me like devs who just don't care.

"Soft" skills are even easier to rattle off on CVs and in JDs, and are worth even less if accompanied by the wrong attitude. Conversely, if a dev has the right attitude, then these skills flourish pretty much automatically. If you care about the code you write, then you'll care about documentation in wiki pages, blog posts, and elsewhere. You'll care about taking the initiative in efforts such as refactoring. You'll care about collaborating with your teammates more. You'll care enough to communicate with your teammates more. "Caring" is the biggest and the most important soft skill of them all!

Image source: Rick Kuwahara

Formal education in programming (from a university or elsewhere) certainly helps with developing your skills, and it can also start you on your journey of caring about code. But you can find it in yourself to care, and you can learn all the tools of the trade, without any formal education. Many successful and famous programmers are proof of that. Conversely, it's possible to have a top-notch formal education up your sleeve, and to still not actually care about code.

It's frustrating when I encounter code that the author clearly didn't care about, at least not in the same ways that I care. For example, say I run into a thousand-line function. Argh, why didn't they break it up?! It might bother me first and foremost because I'm the poor sod who has to modify that code, 5 years later; that is, now it's my problem. But it would also sadden me, because I (2021 me, at least!) would have cared enough to break it up (or at least I'd like to think so), whereas that dev at that point in time didn't care enough to make the effort. (Maybe that dev was me 5 years ago, in which case I'd be doubly disappointed, although wryly happy that present-day me has a higher care factor).

Some aspects of code are easy to start caring about. For example, meaningful naming. You can start doing it right now, no skills required, except common sense. You can, and should, make this New Year's resolution: "I will not name any variable, function, class, file, or anything else x, I will instead name it num_bananas_in_tummy"! Then follow through on that, and the world will be a better place. Amen.

Others are more challenging. For example, test coverage. You need to first learn how to write and run tests in one or more programming languages. That has gotten much easier over the past few decades, depending on the language, but it's still a learning curve. You also need to learn the patterns of writing good tests (which can be a whole specialised career in itself). Plus, you need to understand why tests (particularly unit tests), and test coverage, are important at all. Only then can you start caring. I personally didn't start writing or caring about tests until relatively recently, so I empathise with those of you who haven't yet got there. I hope to see you soon on the other side.

I suspect that this theory of mine applies in much the same way, to virtually all other professions in the world. Particularly professions that involve craftsmanship, but other professions too. Good pharmacists actually care about chemical compounds. Good chefs actually care about fresh produce. Good tailors actually care about fabrics. Good builders actually care about bricks. It's not enough to just care about the customers. It's not enough to just care about the end product. And it's certainly not enough to just care about the money. In order to truly excel at your craft, you've got to actually care about the raw material.

Image source: Brainless Tales

I'm not writing this as an attack on anyone that I know, or that I've worked with, or whose code I've seen. In fact, I've been fortunate in that almost all fellow devs with whom I have crossed paths, are folks who have demonstrated that they care, and who are therefore, in my humble opinion, good devs. And I'm not trying to make myself out to be the patron saint of caring about code, either. Sorry if I sound patronising in this article. I'm not perfect any more than anyone else is. Plenty of people care more than I do. And different people care about different things. And we're all on a journey: I cared about less aspects of code 10 years ago, than I do now; and I hope to care about more aspects of code than I do today, 10 years in the future.

]]>I was also surprised to learn, after doing a modest bit of research, that Tolstoy is seldom mentioned amongst any of the prominent figures in philosophy or metaphysics over the past several centuries. The only articles that even deign to label Tolstoy as a philosopher, are ones that are actually more concerned with Tolstoy as a cult-inspirer, as a pacifist, and as an anarchist.

So, while history has been just and generous in venerating Tolstoy as a novelist, I feel that his contribution to the field of philosophy has gone unacknowledged. This is no doubt in part because Tolstoy didn't consider himself a philosopher, and because he didn't pen any purely philosophical works (published separately from novels and other works), and because he himself criticised the value of such works. Nevertheless, I feel warranted in asking: is Tolstoy a forgotten philosopher?

Image source: Waymarking

Free will in War and Peace

The concept of free will that Tolstoy articulates in War and Peace (particularly in the second epilogue), in a nutshell, is that there are two forces that influence every decision at every moment of a person's life. The first, free will, is what resides within a person's mind (and/or soul), and is what drives him/her to act per his/her wishes. The second, necessity, is everything that resides external to a person's mind / soul (that is, a person's body is also for the most part considered external), and is what strips him/her of choices, and compels him/her to act in conformance with the surrounding environment.

Whatever presentation of the activity of many men or of an individual we may consider, we always regard it as the result partly of man's free will and partly of the law of inevitability.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

A simple example that would appear to demonstrate acting completely according to free will: say you're in an ice cream parlour (with some friends), and you're tossing up between getting chocolate or hazelnut. There's no obvious reason why you would need to eat one flavour vs another. You're partial to both. They're both equally filling, equally refreshing, and equally (un)healthy. You'll be able to enjoy an ice cream with your friends regardless. You're free to choose!

You say: I am not and am not free. But I have lifted my hand and let it fall. Everyone understands that this illogical reply is an irrefutable demonstration of freedom.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter VIII

And another simple example that would appear to demonstrate being completely overwhelmed by necessity: say there's a gigantic asteroid on a collision course for Earth. It's already entered the atmosphere. You're looking out your window and can see it approaching. It's only seconds until it hits. There's no obvious choice you can make. You and all of humanity are going to die very soon. There's nothing you can do!

A sinking man who clutches at another and drowns him; or a hungry mother exhausted by feeding her baby, who steals some food; or a man trained to discipline who on duty at the word of command kills a defenseless man – seem less guilty, that is, less free and more subject to the law of necessity, to one who knows the circumstances in which these people were placed …

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

However, the main point that Tolstoy makes regarding these two forces, is that neither of them does – and indeed, neither of them can – ever exist in absolute form, in the universe as we know it. That is to say, a person is never (and can never be) free to decide anything 100% per his/her wishes; and likewise, a person is never (and can never be) shackled such that he/she is 100% compelled to act under the coercion of external agents. It's a spectrum! And every decision, at every moment of a person's life (and yes, every moment of a person's life involves a decision), lies somewhere on that spectrum. Some decisions are made more freely, others are more constrained. But all decisions result from a mix of the two forces.

In neither case – however we may change our point of view, however plain we may make to ourselves the connection between the man and the external world, however inaccessible it may be to us, however long or short the period of time, however intelligible or incomprehensible the causes of the action may be – can we ever conceive either complete freedom or complete necessity.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter X

So, going back to the first example: there are always some external considerations. Perhaps there's a little bit more chocolate than hazelnut in the tubs, so you'll feel just that little bit guilty if you choose the hazelnut, that you'll be responsible for the parlour running out of it, and for somebody else missing out later. Perhaps there's a deal that if you get exactly the same ice cream five times, you get a sixth one free, and you've already ordered chocolate four times before, so you feel compelled to order it again this time. Or perhaps you don't really want an ice cream at all today, but you feel that peer pressure compels you to get one. You're not completely free after all!

If we consider a man alone, apart from his relation to everything around him, each action of his seems to us free. But if we see his relation to anything around him, if we see his connection with anything whatever – with a man who speaks to him, a book he reads, the work on which he is engaged, even with the air he breathes or the light that falls on the things about him – we see that each of these circumstances has an influence on him and controls at least some side of his activity. And the more we perceive of these influences the more our conception of his freedom diminishes and the more our conception of the necessity that weighs on him increases.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

And, going back to the second example: you always have some control over your own destiny. You have but a few seconds to live. Do you cower in fear, flat on the floor? Do you cling to your loved one at your side? Do you grab a steak knife and hurl it defiantly out the window at the approaching asteroid? Or do you stand there, frozen to the spot, staring awestruck at the vehicle of your impending doom? It may seem pointless, weighing up these alternatives, when you and your whole world are about to be pulverised; but aren't your last moments in life, especially if they're desperate last moments, the ones by which you'll be remembered? And how do you know for certain that there will be nobody left to remember you (and does that matter anyway)? You're not completely bereft of choices after all!

… even if, admitting the remaining minimum of freedom to equal zero, we assumed in some given case – as for instance in that of a dying man, an unborn babe, or an idiot – complete absence of freedom, by so doing we should destroy the very conception of man in the case we are examining, for as soon as there is no freedom there is also no man. And so the conception of the action of a man subject solely to the law of inevitability without any element of freedom is just as impossible as the conception of a man's completely free action.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter X

Background story

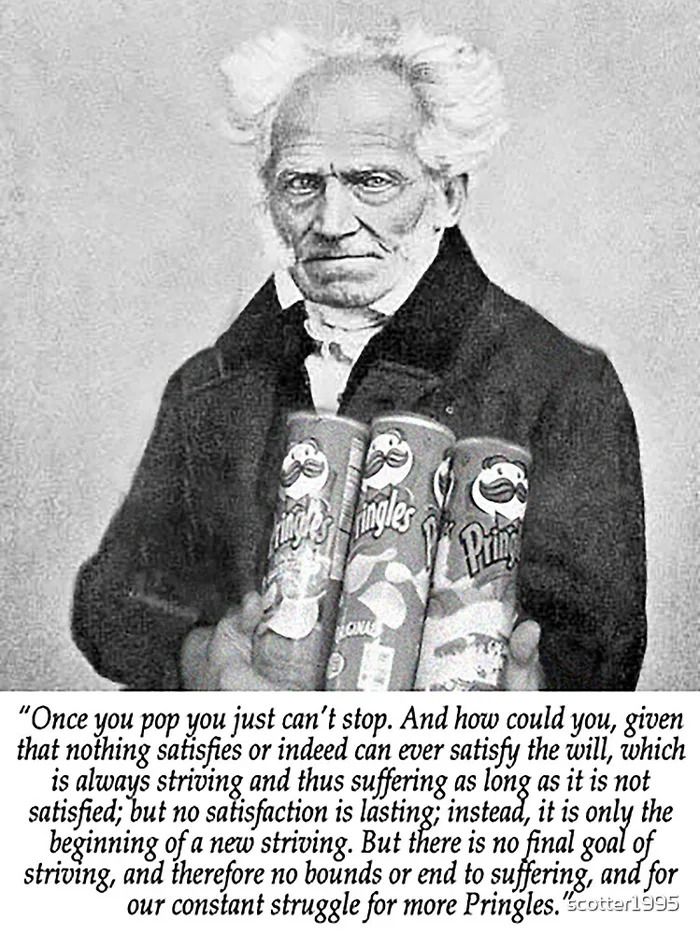

Tolstoy's philosophical propositions in War and Peace were heavily influenced by the ideas of one of his contemporaries, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. In later years, Tolstoy candidly expressed his admiration for Schopenhauer, and he even went so far as to assert that, philosophically speaking, War and Peace was a repetition of Schopenhauer's seminal work The World as Will and Representation.

Schopenhauer's key idea, was that the whole universe (at least, as far as any one person is concerned) consists of two things: the will, which doesn't exist in physical form, but which is the essence of a person, and which contains all of one's drives and desires; and the representation, which is a person's mental model of all that he/she has sensed and interacted with in the physical realm. However, rather than describing the will as the engine of one's freedom, Schopenhauer argues that one is enslaved by the desires imbued in his/her will, and that one is liberated from the will (albeit only temporarily) by aesthetic experience.

Image source: 9gag

Schopenhauer's theories were, in turn, directly influenced by those of Immanuel Kant, who came a generation before him, and who is generally considered the greatest philosopher of the modern era. Kant's ideas (and his works) were many (and I have already written about Kant's ideas recently), but the one of chief concern here – as expounded primarily in his Critique of Pure Reason – was that there are two realms in the universe: the phenomenal, that is, the physical, the universe as we experience and understand it; and the noumenal, that is, a theoretical non-material realm where everything exists as a "thing-in-itself", and about which we know nothing, except for what we are able to deduce via practical reason. Kant argued that the phenomenal realm is governed by absolute causality (that is, by necessity), but that in the noumenal realm there exists absolute free will; and that the fact that a person exists in both realms simultaneously, is what gives meaning to one's decisions, and what makes them able to be measured and judged in terms of ethics.

We can trace the study of free will further through history, from Kant, back to Hume, to Locke, to Descartes, to Augustine, and ultimately back to Plato. In the writings of all these fine folks, over the millennia, there can be found common concepts such as a material vs an ideal realm, a chain of causation, and a free inner essence. The analysis has become ever more refined with each passing generation of metaphysics scholars, but ultimately, it has deviated very little from its roots in ancient times.

It's unique

There are certainly parallels between Tolstoy's War and Peace, and Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation (and, in turn, with other preceding works), but I for one disagree that the former is a mere regurgitation of the latter. Tolstoy is selling himself short. His theory of free will vs necessity is distinct from that of Schopenhauer (and from that of Kant, for that matter). And the way he explains his theory – in terms of a "spectrum of free-ness" – is original as far as I'm aware, and is laudable, if for no other reason, simply because of how clear and easy-to-grok it is.

It should be noted, too, that Tolstoy's philosophical views continued to evolve significantly, later in his life, years after writing War and Peace. At the dawn of the 1900s (by which time he was an old man), Tolstoy was best known for having established his own "rational" version of Christianity, which rejected all the rituals and sacraments of the Orthodox Church, and which gained a cult-like following. He also adopted the lifestyle choices – extremely radical at the time – of becoming vegetarian, of renouncing violence, and of living and dressing like a peasant.

Image source: Flickr

War and Peace is many things. It's an account of the Napoleonic Wars, its bloody battles, its geopolitik, and its tremendous human cost. It's a nostalgic illustration of the old Russian aristocracy – a world long gone – replete with lavish soirees, mountains of servants, and family alliances forged by marriage. And it's a tenderly woven tapestry of the lives of the main protagonists – their yearnings, their liveliest joys, and their deepest sorrows – over the course of two decades. It rightly deserves the praise that it routinely receives, for all those elements that make it a classic novel. But it also deserves recognition for the philosophical argument that Tolstoy peppers throughout the text, and which he dedicates the final pages of the book to making more fully fledged.

]]>However, as anyone exposed to the industry knows, the current state-of-the-art is still plagued by fundamental shortcomings. In a nutshell, the current generation of AI is characterised by big data (i.e. a huge amount of sample data is needed in order to yield only moderately useful results), big hardware (i.e. a giant amount of clustered compute resources is needed, again in order to yield only moderately useful results), and flawed algorithms (i.e. algorithms that, at the end of the day, are based on statistical analysis and not much else – this includes the latest Convolutional Neural Networks). As such, the areas of success (impressive though they may be) are still dwarfed by the relative failures, in areas such as natural language conversation, criminal justice assessment, and art analysis / art production.

In my opinion, if we are to have any chance of reaching a higher plane of AI – one that demonstrates more human-like intelligence – then we must lessen our focus on statistics, mathematics, and neurobiology. Instead, we must turn our attention to philosophy, an area that has traditionally been neglected by AI research. Only philosophy (specifically, metaphysics and epistemology) contains the teachings that we so desperately need, regarding what "reasoning" means, what is the abstract machinery that makes reasoning possible, and what are the absolute limits of reasoning and knowledge.

What is reason?

There are many competing theories of reason, but the one that I will be primarily relying on, for the rest of this article, is that which was expounded by 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason and other texts. Not everyone agrees with Kant, however his is generally considered the go-to doctrine, if for no other reason (no pun intended), simply because nobody else's theories even come close to exploring the matter in such depth and with such thoroughness.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

One of the key tenets of Kant's work, is that there are two distinct types of propositions: an analytic proposition, which can be universally evaluated purely by considering the meaning of the words in the statement; and a synthetic proposition, which cannot be universally evaluated, because its truth-value depends on the state of the domain in question. Further, Kant distinguishes between an a priori proposition, which can be evaluated without any sensory experience; and an a posteriori proposition, which requires sensory experience in order to be evaluated.

So, analytic a priori statements are basically tautologies: e.g. "All triangles have three sides" – assuming the definition of a triangle (a 2D shape with three sides), and assuming the definition of a three-sided 2D shape (a triangle), this must always be true, and no knowledge of anything in the universe (except for those exact rote definitions) is required.

Conversely, synthetic a posteriori statements are basically unprovable real-world observations: e.g. "Neil Armstrong landed on the Moon in 1969" – maybe that "small step for man" TV footage is real, or maybe the conspiracy theorists are right and it was all a hoax; and anyway, even if your name was Buzz Aldrin, and you had seen Neil standing there right next to you on the Moon, how could you ever fully trust your own fallible eyes and your own fallible memory? It's impossible for there to be any logical proof for such a statement, it's only possible to evaluate it based on sensory experience.

Analytic a posteriori statements, according to Kant, are impossible to form.

Which leaves what Kant is most famous for, his discussion of synthetic a priori statements. An example of such a statement is: "A straight line between two points is the shortest". This is not a tautology – the terms "straight line between two points" and "shortest" do not define each other. Yet the statement can be universally evaluated as true, purely by logical consideration, and without any sensory experience. How is this so?

Kant asserts that there are certain concepts that are "hard-wired" into the human mind. In particular, the concepts of space, time, and causality. These concepts (or "forms of sensibility", to use Kant's terminology) form our "lens" of the universe. Hence, we are able to evaluate statements that have a universal truth, i.e. statements that don't depend on any sensory input, but that do nevertheless depend on these "intrinsic" concepts. In the case of the above example, it depends on the concept of space (two distinct points can exist in a three-dimensional space, and the shortest distance between them must be a straight line).

Another example is: "Every event has a cause". This is also universally true; at least, it is according to the intrinsic concepts of time (one event happens earlier in time, and another event happens later in time), and causality (events at one point in space and time, affect events at a different point in space and time). Maybe it would be possible for other reasoning entities (i.e. not humans) to evaluate these statements differently, assuming that such entities were imbued with different "intrinsic" concepts. But it is impossible for a reasoning human to evaluate those statements any other way.

The actual machinery of reasoning, as Kant explains, consists of twelve "categories" of understanding, each of which has a corresponding "judgement". These categories / judgements are essentially logic operations (although, strictly speaking, they predate the invention of modern predicate logic, and are based on Aristotle's syllogism), and they are as follows:

| Group | Categories / Judgements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity |

Unity Universal All trees have leaves |

Plurality Particular Some dogs are shaggy |

Totality Singular This ball is bouncy |

| Quality |

Reality Affirmative Chairs are comfy |

Negation Negative No spoons are shiny |

Limitation Infinite Oranges are not blue |

| Relation |

Inherence / Subsistence Categorical Happy people smile |

Causality / Dependence Hypothetical If it's February, then it's hot |

Community Disjunctive Potatoes are baked or fried |

| Modality |

Existence Assertoric Sharks enjoy eating humans |

Possibility Problematic Beer might be frothy |

Necessity Apodictic 6 times 7 equals 42 |

The cognitive mind is able to evaluate all of the above possible propositions, according to Kant, with the help of the intrinsic concepts (note that these intrinsic concepts are not considered to be "innate knowledge", as defined by the rationalist movement), and also with the help of the twelve categories of understanding.

Reason, therefore, is the ability to evaluate arbitrary propositions, using such cognitive faculties as logic and intuition, and based on understanding and sensibility, which are bridged by way of "forms of sensibility".

AI with intrinsic knowledge

If we consider existing AI with respect to the above definition of reason, it's clear that the capability is already developed maturely in some areas. In particular, existing AI – especially Knowledge Representation (KR) systems – has no problem whatsoever with formally evaluating predicate logic propositions. Existing AI – especially AI based on supervised learning methods – also excels at receiving and (crudely) processing large amounts of sensory input.

So, at one extreme end of the spectrum, there are pure ontological knowledge-base systems such as Cyc, where virtually all of the input into the system consists of hand-crafted factual propositions, and where almost none of the input is noisy real-world raw data. Such systems currently require a massive quantity of carefully curated facts to be on hand, in order to make inferences of fairly modest real-world usefulness.

Then, at the other extreme, there are pure supervised learning systems such as Google's NASNet, where virtually all of the input into the system consists of noisy real-world raw data, and where almost none of the input is human-formulated factual propositions. Such systems currently require a massive quantity of raw data to be on hand, in order to perform classification and regression tasks whose accuracy varies wildly depending on the target data set.

What's clearly missing, is something to bridge these two extremes. And, if transcendental idealism is to be our guide, then that something is "forms of sensibility". The key element of reason that humans have, and that machines currently lack, is a "lens" of the universe, with fundamental concepts of the nature of the universe – particularly of space, time, and causality – embodied in that lens.

Image source: Forbes

What fundamental facts about the universe would a machine require, then, in order to have "forms of sensibility" comparable to that of a human? Well, if we were to take this to the extreme, then a machine would need to be imbued with all the laws of mathematics and physics that exist in our universe. However, let's assume that going to this extreme is neither necessary nor possible, for various reasons, including: we humans are probably only imbued with a subset of those laws (the ones that apply most directly to our everyday existence); it's probably impossible to discover the full set of those laws; and, we will assume that, if a reasoning entity is imbued only with an appropriate subset of those laws, then it's possible to deduce the remainder of the laws (and it's therefore also possible to deduce all other facts relating to observable phenomena in the universe).

I would, therefore, like to humbly suggest, in plain English, what some of these fundamental facts, suitable for comprising the "forms of sensibility" of a reasoning machine, might be:

- There are four dimensions: three space dimensions, and one time dimension

- An object exists if it occupies one or more points in space and time

- An object exists at zero or one points in space, given a particular point in time

- An object exists at zero or more points in time, given a particular point in space

- An event occurs at one point in space and time

- An event is caused by one or more different events at a previous point in time

- Movement is an event that involves an object changing its position in space and time

- An object can observe its relative position in, and its movement through, space and time, using the space concepts of left, right, ahead, behind, up, and down, and using the time concepts of forward and backward

- An object can move in any direction in space, but can only move forward in time

I'm not suggesting that the above list is really a sufficient number of intrinsic concepts for a reasoning machine, nor that all of the above facts are the correct choice nor correctly worded for such a list. But this list is a good start, in my opinion. If an "intelligent" machine were to be appropriately imbued with those facts, then that should be a sufficient foundation for it to evaluate matters of space, time, and causality.

There are numerous other intrinsic aspects of human understanding that it would also, arguably, be essential for a reasoning machine to possess. Foremost of these is the concept of self: does AI need a hard-wired idea of "I"? Other such concepts include matter / substance, inertia, life / death, will, freedom, purpose, and desire. However, it's a matter of debate, rather than a given, whether each of these concepts is fundamental to the foundation of human-like reasoning, or whether each of them is learned and acquired as part of intellectual experience.

Reasoning AI

A machine as discussed so far is a good start, but it's still not enough to actually yield what would be considered human-like intelligence. Cyc, for example, is an existing real-world system that basically already has all these characteristics – it can evaluate logical propositions of arbitrary complexity, based on a corpus (a much larger one than my humble list above) of intrinsic facts, and based on some sensory input – yet no real intelligence has emerged from it.

One of the most important missing ingredients, is the ability to hypothesise. That is, based on the raw sensory input of real-world phenomena, the ability to observe a pattern, and to formulate a completely new, original proposition expressing that pattern as a rule. On top of that, it includes the ability to test such a proposition against new data, and, when the rule breaks, to modify the proposition such that the rule can accommodate that new data. That, in short, is what is known as deductive reasoning.

A child formulates rules in this way. For example, a child observes that when she drops a drinking glass, the glass shatters the moment that it hits the floor. She drops a glass in this way several times, just for fun (plenty of fun for the parents too, naturally), and observes the same result each time. At some point, she formulates a hypothesis along the lines of "drinking glasses break when dropped on the floor". She wasn't born knowing this, nor did anyone teach it to her; she simply "worked it out" based on sensory experience.

Some time later, she drops a glass onto the floor in a different room of the house, still from shoulder-height, but it does not break. So she modifies the hypothesis to be "drinking glasses break when dropped on the kitchen floor" (but not the living room floor). But then she drops a glass in the bathroom, and in that case it does break. So she modifies the hypothesis again to be "drinking glasses break when dropped on the kitchen or the bathroom floor".

But she's not happy with this latest hypothesis, because it's starting to get complex, and the human mind strives for simple rules. So she stops to think about what makes the kitchen and bathroom floors different from the living room floor, and realises that the former are hard (tiled), whereas the latter is soft (carpet). So she refines the hypothesis to be "drinking glasses break when dropped on a hard floor". And thus, based on trial-and-error, and based on additional sensory experience, the facts that comprise her understanding of the world have evolved.

Image source: CoreSight

Some would argue that current state-of-the-art AI is already able to formulate rules, by way of feature learning (e.g. in image recognition). However, a "feature" in a neural network is just a number, either one directly taken from the raw data, or one derived based on some sort of graph function. So when a neural network determines the "features" that correspond to a duck, those features are just numbers that represent the average outline of a duck, the average colour of a duck, and so on. A neural network doesn't formulate any actual facts about a duck (e.g. "ducks are yellow"), which can subsequently be tested and refined (e.g. "bath toy ducks are yellow"). It just knows that if the image it's processing has a yellowish oval object occupying the main area, there's a 63% probability that it's a duck.

Another faculty that the human mind possesses, and that AI currently lacks, is intuition. That is, the ability to reach a conclusion based directly on sensory input, without resorting to logic as such. The exact definition of intuition, and how it differs from instinct, is not clear (in particular, both are sometimes defined as a "gut feeling"). It's also unclear whether or not some form of intuition is an essential ingredient of human-like intelligence.

It's possible that intuition is nothing more than a set of rules, that get applied either before proper logical reasoning has a chance to kick in (i.e. "first resort"), or after proper logical reasoning has been exhausted (i.e. "last resort"). For example, perhaps after a long yet inconclusive analysis of competing facts, regarding whether your Uncle Jim is telling the truth or not when he claims to have been to Mars (e.g. "Nobody has ever been to Mars", "Uncle Jim showed me his medal from NASA", "Mum says Uncle Jim is a flaming crackpot", "Uncle Jim showed me a really red rock"), your intuition settles the matter with the rule: "You should trust your own family". But, on the other hand, it's also possible that intuition is a more elementary mechanism, and that it can't be expressed in the form of logical rules at all: instead, it could simply be a direct mapping of "situations" to responses.

Is reason enough?

In order to test whether a hypothetical machine, as discussed so far, is "good enough" to be considered intelligent, I'd like to turn to one of the domains that current-generation AI is already pursuing: criminal justice assessment. One particular area of this domain, in which the use of AI has grown significantly, is determining whether an incarcerated person should be approved for parole or not. Unsurprisingly, AI's having input into such a decision has so far, in real life, not been considered altogether successful.

The current AI process for this is based almost entirely on statistical analysis. That is, the main input consists of simple numeric parameters, such as: number of incidents reported during imprisonment; level of severity of the crime originally committed; and level of recurrence of criminal activity. The input also includes numerous profiling parameters regarding the inmate, such as: racial / ethnic group; gender; and age. The algorithm, regardless of any bells and whistles it may claim, is invariably simply answering the question: for other cases with similar input parameters, were they deemed eligible for parole? And if so, did their conduct after release demonstrate that they were "reformed"? And based on that, is this person eligible for parole?

Current-generation AI, in other words, is incapable of considering a single such case based on its own merits, nor of making any meaningful decision regarding that case. All it can do, is compare the current case to its training data set of other cases, and determine how similar the current case is to those others.

A human deciding parole eligibility, on the other hand, does consider the case in question based on its own merits. Sure, a human also considers the numeric parameters and the profiling parameters that a machine can so easily evaluate. But a human also considers each individual event in the inmate's history as a stand-alone fact, and each such fact can affect the final decision differently. For example, perhaps the inmate seriously assaulted other inmates twice while imprisoned. But perhaps he also read 150 novels, and finished a university degree by correspondence. These are not just statistics, they're facts that must be considered, and each fact must refine the hypothesis whose final form is either "this person is eligible for parole", or "this person is not eligible for parole".

A human is also influenced by morals and ethics, when considering the character of another human being. So, although the question being asked is officially: "is this person eligible for parole?", the question being considered in the judge's head may very well actually be: "is this person good or bad?". Should a machine have a concept of ethics, and/or of good vs bad, and should it apply such ethics when considering the character of an individual human? Most academics seem to think so.

According to Kant, ethics is based on a foundation of reason. But that doesn't mean that a reasoning machine is automatically an ethical machine, either. Does AI need to understand ethics, in order to possess what we would consider human-like intelligence?

Although decisions such as parole eligibility are supposed to be objective and rational, a human is also influenced by emotions, when considering the character of another human being. Maybe, despite the evidence suggesting that the inmate is not reformed, the judge is stirred by a feeling of compassion and pity, and this feeling results in parole being granted. Or maybe, despite the evidence being overwhelmingly positive, the judge feels fear and loathing towards the inmate, mainly because of his tough physical appearance, and this feeling results in parole being denied.

Should human-like AI possess the ability to be "stirred" by such emotions? And would it actually be desirable for AI to be affected by such emotions, when evaluating the character of an individual human? Some such emotions might be considered positive, while others might be considered negative (particularly from an ethical point of view).

I think the ultimate test in this domain – perhaps the "Turing test for criminal justice assessment" – would be if AI were able to understand, and to properly evaluate, this great parole speech, which is one of my personal favourite movie quotes:

There's not a day goes by I don't feel regret. Not because I'm in here, or because you think I should. I look back on the way I was then: a young, stupid kid who committed that terrible crime. I want to talk to him. I want to try and talk some sense to him, tell him the way things are. But I can't. That kid's long gone and this old man is all that's left. I got to live with that. Rehabilitated? It's just a bulls**t word. So you can go and stamp your form, Sonny, and stop wasting my time. Because to tell you the truth, I don't give a s**t.

"Red" (Morgan Freeman)

Image source: YouTube

In the movie, Red's parole was granted. Could we ever build an AI that could also grant parole in that case, and for the same reasons? On top of needing the ability to reason with real facts, and to be affected by ethics and by emotion, properly evaluating such a speech requires the ability to understand humour – black humour, no less – along with apathy and cynicism. No small task.

Conclusion

Sorry if you were expecting me to work wonders in this article, and to actually teach the world how to build artificial intelligence that reasons. I don't have the magic answer to that million dollar question. However, I hope I have achieved my aim here, which was to describe what's needed in order for it to even be possible for such AI to come to fruition.

It should be clear, based on what I've discussed here, that most current-generation AI is based on a completely inadequate foundation for even remotely human-like intelligence. Chucking big data at a statistic-crunching algorithm on a fat cluster might be yielding cool and even useful results, but it will never yield intelligent results. As centuries of philosophical debate can teach us – if only we'd stop and listen – human intelligence rests on specific building blocks. These include, at the very least, an intrinsic understanding of time, space, and causality; and the ability to hypothesise based on experience. If we are to ever build a truly intelligent artificial agent, then we're going to have to figure out how to imbue it with these things.

Further reading

- Immanuel Kant: Aesthetics

- The Mismatch Between Human and Machine Knowledge (1994)

- Gödel, Consciousness and the Weak vs. Strong AI Debate

- Transforming Kantian Aesthetic Principles into Qualitative Hermeneutics for Contemplative AGI Agents (2018)

- Recognizing context is still hard in Machine Learning — here’s how to tackle it

- Towards Deep Symbolic Reinforcement Learning (2016)

- Generality in Artificial Intelligence (1987)

- The Symbol Grounding Problem (1990)

- Aristotle’s Ten Categories

- Computational Beauty: Aesthetic Judgment at the Intersection of Art and Science (2014)

- Philosophy of artificial intelligence

- A proposal for ethically traceable artificial intelligence (2017)

- Commonsense knowledge (artificial intelligence)

- Kant's Critique of Pure Reason

- Schopenhauer on Space, Time, Causality and Matter: A Physical Re-examination (2018)

- A Brief Introduction to Temporality and Causality (2010)

- Sequences of Mechanisms for Causal Reasoning in Artificial Intelligence (2013)

Image source: Day of the Robot.

Most discussion of late seems to treat this encroaching joblessness entirely as an economic issue. Families without incomes, spiralling wealth inequality, broken taxation mechanisms. And, consequently, the solutions being proposed are mainly economic ones. For example, a Universal Basic Income to help everyone make ends meet. However, in my opinion, those economic issues are actually relatively easy to address, and as a matter of sheer necessity we will sort them out sooner or later, via a UBI or via whatever else fits the bill.

The more pertinent issue is actually a social and a psychological one. Namely: how will people keep themselves occupied in such a world? How will people nourish their ambitions, feel that they have a purpose in life, and feel that they make a valuable contribution to society? How will we prevent the malaise of despair, depression, and crime from engulfing those who lack gainful enterprise? To borrow the colourful analogy that others have penned: assuming that there's food on the table either way, how do we head towards a Star Trek rather than a Mad Max future?

Keep busy

The truth is, since the Industrial Revolution, an ever-expanding number of people haven't really needed to work anyway. What I mean by that is: if you think about what jobs are actually about providing society with the essentials such as food, water, shelter, and clothing, you'll quickly realise that fewer people than ever are employed in such jobs. My own occupation, web developer, is certainly not essential to the ongoing survival of society as a whole. Plenty of other occupations, particularly in the services industry, are similarly remote from humanity's basic needs.

So why do these jobs exist? First and foremost, demand. We live in a world of free markets and capitalism. So, if enough people decide that they want web apps, and those people have the money to make it happen, then that's all that's required for "web developer" to become and to remain a viable occupation. Second, opportunity. It needs to be possible to do that thing known as "developing web apps" in the first place. In many cases, the opportunity exists because of new technology; in my case, the Internet. And third, ambition. People need to have a passion for what they do. This means that, ideally, people get to choose an occupation of their own free will, rather than being forced into a certain occupation by their family or by the government. If a person has a natural talent for his or her job, and if a person has a desire to do the job well, then that benefits the profession as a whole, and, in turn, all of society.

Those are the practical mechanisms through which people end up spending much of their waking life at work. However, there's another dimension to all this, too. It is very much in the interest of everyone that makes up "the status quo" – i.e. politicians, the police, the military, heads of big business, and to some extent all other "well to-do citizens" – that most of society is caught up in the cycle of work. That's because keeping people busy at work is the most effective way of maintaining basic law and order, and of enforcing control over the masses. We have seen throughout history that large-scale unemployment leads to crime, to delinquency and, ultimately, to anarchy. Traditionally, unemployment directly results in poverty, which in turn directly results in hunger. But even if the unemployed get their daily bread – even if the crisis doesn't reach let them eat cake proportions – they are still at risk of falling to the underbelly of society, if for no other reason, simply due to boredom.

So, assuming that a significantly higher number of working-age men and women will have significantly fewer job prospects in the immediate future, what are we to do with them? How will they keep themselves occupied?

The Games

I propose that, as an alternative to traditional employment, these people engage in large-scale, long-term, government-sponsored, semi-recreational activities. These must be activities that: (a) provide some financial reward to participants; (b) promote physical health and social well-being; and (c) make a tangible positive contribution to society. As a massive tongue-in-cheek, I call this proposal "The Jobless Games".

My prime candidate for such an activity would be a long-distance walk. The journey could take weeks, months, even years. Participants could number in the hundreds, in the thousands, even in the millions. As part of the walk, participants could do something useful, too; for example, transport non-urgent goods or mail, thus delivering things that are actually needed by others, and thus competing with traditional freight services. Walking has obvious physical benefits, and it's one of the most social things you can do while moving and being active. Such a journey could also be done by bicycle, on horseback, or in a variety of other modes.

Image source: The New Paper.

Other recreational programs could cover the more adventurous activities, such as climbing, rafting, and sailing. However, these would be less suitable, because: they're far less inclusive of people of all ages and abilities; they require a specific climate and geography; they're expensive in terms of equipment and expertise; they're harder to tie in with some tangible positive end result; they're impractical in very large groups; and they damage the environment if conducted on too large a scale.

What I'm proposing is not competitive sport. These would not be races. I don't see what having winners and losers in such events would achieve. What I am proposing is that people be paid to participate in these events, out of the pocket of whoever has the money, i.e. governments and big business. The conditions would be simple: keep up with the group, and behave yourself, and you keep getting paid.

I see such activities co-existing alongside whatever traditional employment is still available in future; and despite all the doom and gloom predictions, the truth is that there always has been real work out there, and there always will be. My proposal is that, same as always, traditional employment pays best, and thus traditional employment will continue to be the most attractive option for how to spend one's days. Following that, "The Games" pay enough to get by on, but probably not enough to enjoy all life's luxuries. And, lastly, as is already the case in most first-world countries today, for the unemployed there should exist a social security payment, and it should pay enough to cover life's essentials, but no more than that. We already pay people sit down money; how about a somewhat more generous payment of stand up money?

Along with these recreational activities that I've described, I think it would also be a good idea to pay people for a lot of the work that is currently done by volunteers without financial reward. In a future with less jobs, anyone who decides to peel potatoes in a soup kitchen, or to host bingo games in a nursing home, or to take disabled people out for a picnic, should be able to support him- or herself and to live in a dignified manner. However, as with traditional employment, there are also only so many "volunteer" positions that need filling, and even with that sector significantly expanded, there would still be many people left twiddling their thumbs. Which is why I think we need some other solution, that will easily and effectively get large numbers of people on their feet. And what better way to get them on their feet, than to say: take a walk!

Large-scale, long-distance walks could also solve some other problems that we face at present. For example, getting a whole lot of people out of our biggest and most crowded cities, and "going on tour" to some of our smallest and most neglected towns, would provide a welcome economic boost to rural areas, considering all the support services that such activities would require; while at the same time, it would ease the crowding in the cities, and it might even alleviate the problem of housing affordability, which is acute in Australia and elsewhere. Long-distance walks in many parts of the world – particularly in Europe – could also provide great opportunities for an interchange of language and culture.

In summary

There you have it, my humble suggestion to help fill the void in peoples' lives in the future. There are plenty of other things that we could start paying people to do, that are more intellectual and that make a more tangible contribution to society: e.g. create art, be spiritual, and perform in music and drama shows. However, these things are too controversial for the government to support on such a large scale, and their benefit is a matter of opinion. I really think that, if something like this is to have a chance of succeeding, it needs to be dead simple and completely uncontroversial. And what could be simpler than walking?

Whatever solutions we come up with, I really think that we need to start examining the issue of 21st-century job redundancy from this social angle. The economic angle is a valid one too, but it has already been analysed quite thoroughly, and it will sort itself out with a bit of ingenuity. What we need to start asking now is: for those young, fit, ambitious people of the future that lack job prospects, what activity can they do that is simple, social, healthy, inclusive, low-impact, low-cost, and universal? I'd love to hear any further suggestions you may have.

]]>

Image source: Giant Chocolate chip cookie recipe.

I'd never before stopped to think about whether or not there was a limit to how much you can put in a cookie. Usually, cookies only store very small string values, such as a session ID, a tracking code, or a browsing preference (e.g. "tile" or "list" for search results). So, usually, there's no need to consider its size limits.

However, while working on a new side project of mine that heavily uses session storage, I discovered this limit the hard (to debug) way. Anyway, now I've got one more adage to add to my developer's phrasebook: if you're trying to store more than 4KiB in a cookie, you're doing it wrong.

Actually, according to the web site Browser Cookie Limits, the safe "lowest common denominator" maximum size to stay below is 4093 bytes. Also check out the Stack Overflow discussion, What is the maximum size of a web browser's cookie's key?, for more commentary regarding the limit.

In my case – working with Flask, which depends on Werkzeug – trying to store an oversized cookie doesn't throw any errors, it simply fails silently. I've submitted a patch to Werkzeug, to make oversized cookies raise an exception, so hopefully it will be more obvious in future when this problem occurs.

It appears that this is not an isolated issue; many web frameworks and libraries fail silently with storage of too-big cookies. It's the case with Django, where the decision was made to not fix it, for technical reasons. Same story with CodeIgniter. Seems that Ruby on Rails is well-behaved and raises exceptions. Basically, your mileage may vary: don't count on your framework of choice alerting you, if you're being a cookie monster.

Also, as several others have pointed out, trying to store too much data in cookies is a bad idea anyway, because that data travels with every HTTP request and response, so it should be as small as possible. As I learned, if you find that you're dealing with non-trivial amounts of session data, then ditch client-side storage for the app in question, and switch to server-side session data storage (preferably using something like Memcached or Redis).

]]>If your design is sufficiently custom that you're writing theme-level Views template files, then chances are that you'll be in danger of creating duplicate templates. I've committed this sin on numerous sites over the past few years. On many occasions, my Views templates were 100% identical, and after making a change in one template, I literally copy-pasted and renamed the file, to update the other templates.

Until, finally, I decided that enough is enough – time to get DRY!

Being less repetitive with your Views templates is actually dead simple. Let's say you have three identical files – views-view-fields--search_this_site.tpl.php, views-view-fields--featured_articles.tpl.php, and views-view-fields--articles_archive.tpl.php. Here's how you clean up your act:

- Delete the latter two files.

- Add this to your theme's

template.phpfile:

<?php function mytheme_preprocess_views_view_fields(&$vars) { if (in_array( $vars['view']->name, array( 'search_this_site', 'featured_articles', 'articles_archive'))) { $vars['theme_hook_suggestions'][] = 'views_view_fields__search_this_site'; } } - Clear your cache (that being the customary final step when doing anything in Drupal, of course).

I've found that views-view-fields.tpl.php-based files are the biggest culprits for duplication; but you might have some other Views templates in need of cleaning up, too, such as:

<?php

function mytheme_preprocess_views_view(&$vars) {

if (in_array(

$vars['view']->name, array(

'search_this_site',

'featured_articles',

'articles_archive'))) {

$vars['theme_hook_suggestions'][] =

'views_view__search_this_site';

}

}

And, if your views include a search / filtering form, perhaps also:

<?php

function mytheme_preprocess_views_exposed_form(&$vars) {

if (in_array(

$vars['view']->name, array(

'search_this_site',

'featured_articles',

'articles_archive'))) {

$vars['theme_hook_suggestions'][] =

'views_exposed_form__search_this_site';

}

}

That's it – just a quick tip from me for today. You can find out more about this technique on the Custom Theme Hook Suggestions documentation page, although I couldn't find an example for Views there, nor anywhere else online for that matter; hence this article. Hopefully this results in a few kilobytes saved, and (more importantly) a lot of unnecessary copy-pasting of template files saved, for fellow Drupal devs and themers.

]]>Societal vices have always been bountiful. Back in the ol' days, it was just the usual suspects. War. Violence. Greed. Corruption. Injustice. Propaganda. Lewdness. Alcoholism. To name a few. In today's world, still more scourges have joined in the mix. Consumerism. Drug abuse. Environmental damage. Monolithic bureaucracy. And plenty more.

There always have been some folks who elect to isolate themselves from the masses, to renounce their mainstream-ness, to protect themselves from all that nastiness. And there always will be. Nothing wrong with doing so.

However, there's a difference between protecting oneself from "the evils of society", and blinding oneself to their very existence. Sometimes this difference is a fine line. Particularly in the case of families, where parents choose to shield from the Big Bad World not only themselves, but also their children. Protection is noble and commendable. Blindfolding, in my opinion, is cowardly and futile.

Image source: greenskullz1031 on Photobucket.

Seclusion

There are plenty of examples from bygone times, of historical abstainers from mainstream society. Monks and nuns, who have for millenia sought serenity, spirituality, abstinence, and isolation from the material. Hermits of many varieties: witches, grumpy old men / women, and solitary island-dwellers.

Religion has long been an important motive for seclusion. Many have settled on a reclusive existence as their solution to avoiding widespread evils and being closer to G-d. Other than adult individuals who choose a monastic life, there are also whole communities, composed of families with children, who live in seclusion from the wider world. The Amish in rural USA are probably the most famous example, and also one of the longest-running such communities. Many ultra-orthodox Jewish communities, particularly within present-day Israel, could also be considered as secluded.

Image source: Wikipedia: Amish.

More recently, the "commune living" hippie phenomenon has seen tremendous growth worldwide. The hippie ideology is, of course, generally an anti-religious one, with its acceptance of open relationships, drug use, lack of hierarchy, and often a lack of any formal G-d. However, the secluded lifestyle of hippie communes is actually quite similar to that of secluded religious groups. It's usually characterised by living amidst, and in tune with, nature; rejecting modern technology; and maintaining a physical distance from regular urban areas. The left-leaning members of these communities tend to strongly shun consumerism, and to promote serenity and spirituality, much like their G-d fearing comrades.

In a bubble

Like the members of these communities, I too am repulsed by many of the "evils" within the society in which we live. Indeed, the idea of joining such a community is attractive to me. It would be a pleasure and a relief to shut myself out from the blight that threatens me, and from everyone that's "infected" by it. Life would be simpler, more peaceful, more wholesome.

I empathise with those who have chosen this path in life. Just as it's tempting to succumb to all the world's vices, so too is it tempting to flee from them. However, such people are also living in a bubble. An artificial world, from which the real world has been banished.

What bothers me is not so much the independent adult people who have elected for such an existence. Despite all the faults of the modern world, most of us do at least enjoy far-reaching liberty. So, it's a free land, and adults are free to live as they will, and to blind themselves to what they will.

What does bother me, is that children are born and raised in such an existence. The adult knows what it is that he or she is shut off from, and has experienced it before, and has decided to discontinue experiencing it. The child, on the other hand, has never been exposed to reality, he or she knows only the confines of the bubble. The child is blind, but to what, it knows not.

Image source: CultureLab: Breaking out of the internet filter bubble.

This is a cowardly act on the part of the parents. It's cowardly because a child only develops the ability to combat and to reject the world's vices, such as consumerism or substance abuse, by being exposed to them, by possibly experimenting with them, and by making his or her own decisions. Parents that are serious about protecting their children do expose them to the Big Bad World, they do take risks; but they also do the hard yards in preparing their children for it: they ensure that their children are raised with education, discipline, and love.

Blindfolding children to the reality of wider society is also futile — because, sooner or later, whether still as children or later as adults, the Big Bad World exposes itself to all, whether you like it or not. No Amish countryside, no hippie commune, no far-flung island, is so far or so disconnected from civilisation that its inhabitants can be prevented from ever having contact with it. And when the day of exposure comes, those that have lived in their little bubble find themselves totally unprepared for the very "evils" that they've supposedly been protected from for all their lives.

Keep it balanced

In my opinion, the best way to protect children from the world's vices, is to expose them in moderation to the world's nasty underbelly, while maintaining a stable family unit, setting a strong example of rejecting the bad, and ensuring a solid education. That is, to do what the majority of the world's parents do. That's right: it's a formula that works reasonably well for billions of people, and that has been developed over thousands of years, so there must be some wisdom to it.

Obviously, children need to be protected from dangers that could completely overwhelm them. Bringing up a child in a favela environment is not ideal, and sometimes has horrific consequences, just watch City of G-d if you don't believe me. But then again, blindfolding is the opposite extreme; and one extreme can be as bad as the other. Getting the balance somewhere in between is the key.

]]>There are plenty of articles round and about the interwebz, aimed more at the practical side of coming to Chile: i.e. tips regarding how to get around; lists of rough prices of goods / services; and crash courses in Chilean Spanish. There are also a number of commentaries on the cultural / social differences between Chile and elsewhere – on the national psyche, and on the political / economic situation.

My endeavour is to avoid this article from falling neatly into either of those categories. That is, I'll be covering some eccentricities of Chile that aren't practical tips as such, although knowing about them may come in handy some day; and I'll be covering some anecdotes that certainly reflect on cultural themes, but that don't pretend to paint the Chilean landscape inside-out, either.

Que disfrutiiy, po.

Image sources: Times Journeys / 2GB.

Fin de mes

Here in Chile, all that is money-related is monthly. You pay everything monthly (your rent, all your bills, all membership fees e.g. gym, school / university fees, health / home / car insurance, etc); and you get paid monthly (if you work here, which I don't). I know that Chile isn't the only country with this modus operandi: I believe it's the European system; and as far as I know, it's the system in various other Latin American countries too.

In Australia – and as far as I know, in most English-speaking countries – there are no set-in-stone rules about the frequency with which you pay things, or with which you get paid. Bills / fees can be weekly, monthly, quarterly, annual… whatever (although rent is generally charged and is talked about as a weekly cost). Your pay cheque can be weekly, fortnightly, monthly, quarterly… equally whatever (although we talk about "how much you earn" annually, even though hardly anyone is paid annually). I guess the "all monthly" system is more consistent, and I guess it makes it easier to calculate and compare costs. However, having grown up with the "whatever" system, "all monthly" seems strange and somewhat amusing to me.

In Chile, although payment due dates can be anytime throughout the month, almost everyone receives their salary at fin de mes (the end of the month). I believe the (rough) rule is: the dosh arrives on the actual last day of the month if it's a regular weekday; or the last regular weekday of the month, if the actual last day is a weekend or public holiday (which is quite often, since Chile has a lot of public holidays – twice as many as Australia!).

This system, combined with the last-minute / impulsive form of living here, has an effect that's amusing, frustrating, and (when you think about it) depressingly predictable. As I like to say (in jest, to the locals): in Chile, it's Christmas time every end-of-month! The shops are packed, the restaurants are overflowing, and the traffic is insane, on the last day and the subsequent few days of each month. For the rest of the month, all is quiet. Especially the week before fin de mes, which is really Struggle Street for Chileans. So extreme is this fin de mes culture, that it's even busy at the petrol stations at this time, because many wait for their pay cheque before going to fill up the tank.

This really surprised me during my first few months in Chile. I used to ask: ¿Qué pasa? ¿Hay algo important hoy? ("What's going on? Is something important happening today?"). To which locals would respond: Es fin de mes! Hoy te pagan! ("It's end-of-month! You get paid today!"). These days, I'm more-or-less getting the hang of the cycle; although I don't think I'll ever really get my head around it. I'm pretty sure that, even if we did all get paid on the same day in Australia (which we don't), we wouldn't all rush straight to the shops in a mad stampede, desperate to spend the lot. But hey, that's how life is around here.

Cuotas

Continuing with the socio-economic theme, and also continuing with the "all-monthly" theme: another Chile-ism that will never cease to amuse and amaze me, is the omnipresent cuotas ("monthly instalments"). Chile has seen a spectacular rise in the use of credit cards, over the last few decades. However, the way these credit cards work is somewhat unique, compared with the usual credit system in Australia and elsewhere.

Any time you make a credit card purchase in Chile, the cashier / shop assistant will, without fail, ask you: ¿cuántas cuotas? ("how many instalments?"). If you're using a foreign credit card, like myself, then you must always answer: sin cuotas ("no instalments"). This is because, even if you wanted to pay for your purchase in chunks over the next 3-24 months (and trust me, you don't), you can't, because this system of "choosing at point of purchase to pay in instalments" only works with local Chilean cards.

Chile's current president, the multi-millionaire Sebastian Piñera, played an important part in bringing the credit card to Chile, during his involvement with the banking industry before entering politics. He's also generally regarded as the inventor of the cuotas system. The ability to choose your monthly instalments at point of sale is now supported by all credit cards, all payment machines, all banks, and all credit-accepting retailers nationwide. The system has even spread to some of Chile's neighbours, including Argentina.

Unfortunately, although it seems like something useful for the consumer, the truth is exactly the opposite: the cuotas system and its offspring, the cuotas national psyche, has resulted in the vast majority of Chileans (particularly the less wealthy among them) being permanently and inescapably mired in debt. What's more, although some of the cuotas offered are interest-free (with the most typical being a no-interest 3-instalment plan), some plans and some cards (most notoriously the "department store bank" cards) charge exhorbitantly high interest, and are riddled with unfair and arcane terms and conditions.

Última hora

Chile's a funny place, because it's so "not Latin America" in certain aspects (e.g. much better infrastructure than most of its neighbours), and yet it's so "spot-on Latin America" in other aspects. The última hora ("last-minute") way of living definitely falls within the latter category.

In Chile, people do not make plans in advance. At least, not for anything social- or family-related. Ask someone in Chile: "what are you doing next weekend?" And their answer will probably be: "I don't know, the weekend hasn't arrived yet… we'll see!" If your friends or family want to get together with you in Chile, don't expect a phone call the week before. Expect a phone call about an hour before.

I'm not just talking about casual meet-ups, either. In Chile, expect to be invited to large birthday parties a few hours before. Expect to know what you're doing for Christmas / New Year a few hours before. And even expect to know if you're going on a trip or not, a few hours before (and if it's a multi-day trip, expect to find a place to stay when you arrive, because Chileans aren't big on making reservations).

This is in stark contrast to Australia, where most people have a calendar to organise their personal life (something extremely uncommon in Chile), and where most peoples' evenings and weekends are booked out at least a week or two in advance. Ask someone in Sydney what their schedule is for the next week. The answer will probably be: "well, I've got yoga tomorrow evening, I'm catching up with Steve for lunch on Wednesday, big party with some old friends on Friday night, beach picnic on Saturday afternoon, and a fancy dress party in the city on Saturday night." Plus, ask them what they're doing in two months' time, and they'll probably already have booked: "6 nights staying in a bungalow near Batemans Bay".

The última hora system is both refreshing and frustrating, for a planned-ahead foreigner like myself. It makes you realise just how regimented, inflexible, and lacking in spontenaeity life can be in your home country. But, then again, it also makes you tear your hair out, when people make zero effort to co-ordinate different events and to avoid clashes. Plus, it makes for many an awkward silence when the folks back home ask the question that everybody asks back home, but that nobody asks around here: "so, what are you doing next weekend?" Depends which way the wind blows.

Sit down

In Chile (and elsewhere nearby, e.g. Argentina), you do not eat or drink while standing. In most bars in Chile, everyone is sitting down. In fact, in general there is little or no "bar" area, in bars around here; it's all tables and chairs. If there are no tables or chairs left, people will go to a different bar, or wait for seats to become vacant before eating / drinking. Same applies in the home, in the park, in the garden, or elsewhere: nobody eats or drinks standing up. Not even beer. Not even nuts. Not even potato chips.

In Australia (and in most other English-speaking countries, as far as I know), most people eat and drink while standing, in a range of different contexts. If you're in a crowded bar or pub, eating / drinking / talking while standing is considered normal. Likewise for a big house party. Same deal if you're in the park and you don't want to sit on the grass. I know it's only a little thing; but it's one of those little things that you only realise is different in other cultures, after you've lived somewhere else.

It's also fairly common to see someone eating their take-away or other food while walking, in Australia. Perhaps some hot chips while ambling along the beach. Perhaps a sandwich for lunch while running (late) to a meeting. Or perhaps some lollies on the way to the bus stop. All stuff you wouldn't blink twice at back in Oz. In Chile, that is simply not done. Doesn't matter if you're in a hurry. It couldn't possibly be such a hurry, that you can't sit down to eat in a civilised fashion. The Chilean system is probably better for your digestion! And they have a point: perhaps the solution isn't to save time by eating and walking, but simply to be in less of a hurry?

Image source: Dondequieroir.

Walled and shuttered

One of the most striking visual differences between the Santiago and Sydney streetscapes, in my opinion, is that walled-up and shuttered-up buildings are far more prevalent in the former than in the latter. Santiago is not a dangerous city, by Latin-American or even by most Western standards; however, it often feels much less secure than it should, particularly at night, because often all you can see around you is chains, padlocks, and sturdy grilles. Chileans tend to shut up shop Fort Knox-style.

Walk down Santiago's Ahumada shopping strip in the evening, and none of the shopfronts can be seen. No glass, no lit-up signs, no posters. Just grey steel shutters. Walk down Sydney's Pitt St in the evening, and – even though all the shops close earlier than in Santiago – it doesn't feel like a prison, it just feels like a shopping area after-hours.

In Chile, virtually all houses and apartment buildings are walled and gated. Also, particularly ugly in my opinion, schools in Chile are surrounded by high thick walls. For both houses and schools, it doesn't matter if they're upper- or lower-class, nor what part of town they're in: that's just the way they build them around here. In Australia, on the other hand, you can see most houses and gardens from the street as you go past (and walled-in houses are criticised as being owned by "paranoid people"); same with schools, which tend to be open and abundant spaces, seldom delimiting their boundary with anything more than a low mesh fence.

As I said, Santiago isn't a particularly dangerous city, although it's true that robbery is far more common here than in Sydney. The real difference, in my opinion, is that Chileans simply don't feel safe unless they're walled in and shuttered up. Plus, it's something of a vicious cycle: if everyone else in the city has a wall around their house, and you don't, then chances are that your house will be targeted, not because it's actually easier to break into than the house next door (which has a wall that can be easily jumped over anyway), but simply because it looks more exposed. Anyway, I will continue to argue to Chileans that their country (and the world in general) would be better with less walls and less barriers; and, no doubt, they will continue to stare back at me in bewilderment.

Image source: eszsara (Flickriver).

In summary

So, there you have it: a few of my random observations about life in Santiago, Chile. I hope you've found them educational and entertaining. Overall, I've enjoyed my time in this city; and while I'm sometimes critical of and poke fun at Santiago's (and Chile's) peculiarities, I'm also pretty sure I'll miss then when I'm gone. If you have any conclusions of your own regarding life in this big city, feel free to share them below.

]]>

Two weeks ago, the Gillard government succeeded in passing legislation for a new carbon tax through the lower house of the Australian federal parliament. Shortly after, opposition leader Tony Abbott made a "pledge in blood", promising that: "We will repeal the tax, we can repeal the tax, we must repeal the tax".

The passing of the carbon tax bill represents a concerted effort spanning at least ten years, made possible by the hard work and the sacrifice of numerous Australians (at all levels, including at the very top). Australia is the highest per-capita greenhouse gas emitter in the developed world. We need climate change legislation enactment urgently, and this bill represents a huge step towards that endeavour.

I don't usually publish direct political commentary here. Nor do I usually name and shame. But I feel compelled to make an exception in this case. For me, Tony Abbott's response to the carbon tax can only possibly be addressed in one way. He leaves us with no option. If this man has sworn to repeal the good work that has flourished of late, then the solution is simple. Tony Abbott must never lead this country. The consequences of his ascension to power would be, in a nutshell, diabolical.

So, join me in making a blood pledge to never vote for Tony Abbott.

Fortunately, as commentators have pointed out, it would actually be extremely difficult — if not downright impossible — for an Abbott-led government to repeal the tax in practice (please G-d may such government never come to pass). Also fortunate is the fact that support for the anti-carbon-tax movement is much less than Abbott makes it out to be, via his dramatic media shenanigans.

Of course, there are also a plethora of other reasons to not vote for tony. His hard-line Christian stance on issues such as abortion, gay marriage, and euthanasia. His xenophobia towards what he perceives as "the enemies of our Christian democratic society", i.e. Muslims and other minority groups. His policies regarding Aboriginal rights. His pathetic opportunism of the scare-campaign bandwagon to "stop the boats". His unashamed labelling of himself as "Howard 2.0". His budgie smugglers (if somehow — perhaps due to a mental disability — nothing else about the possibility of Abbott being PM scares the crap out of you, at least consider this!).

In last year's Federal election, I was truly terrified at the real and imminent possibility that Abbott could actually win (and I wasn't alone). I was aghast at how incredibly close he came to claiming the top job, although ultimately very relieved in seeing him fail (a very Bush-esque affair, in my opinion, was Australia's post-election kerfuffle of 2010 — which I find fitting, since I find Abbott almost as nauseating as the legendarily dimwitted G-W himself).

I remain in a state of trepidation, as long as Abbott continues to have a chance of leading this country. Because, laugh as we may at Gillard's 2010 election slogan of "Moving Forward Together", I can assure you that Abbott's policy goes more along the line of "Moving Backward Stagnantly".

Image courtesy of The Wire.