Communism – or, to be more precise, Marxism – made sweeping promises of a rosy utopian world society: all people are equal; from each according to his ability, to each according to his need; the end of the bourgeoisie, the rise of the proletariat; and the end of poverty. In reality, the nature of the communist societies that emerged during the 20th century was far from this grandiose vision.

Communism obviously was not successful in terms of the most obvious measure: namely, its own longevity. The world's first and its longest-lived communist regime, the Soviet Union, well and truly collapsed. The world's most populous country, the People's Republic of China, is stronger than ever, but effectively remains communist in name only (as does its southern neighbour, Vietnam).

However, this article does not seek to measure communism's success based on the survival rate of particular governments; nor does it seek to analyse (in any great detail) why particular regimes failed (and there's no shortage of other articles that do analyse just that). More important than whether the regimes themselves prospered or met their demise, is their legacy and their long-term impact on the societies that they presided over. So, how successful was the communism experiment, in actually improving the economic, political, and cultural conditions of the populations that experienced it?

Image source: FunnyJunk.

Success:

- Health care in Cuba (internationally recognised as being one of the world's best and most accessible public health care systems)

- The arts (Soviet theatre and Soviet ballet received funding and support for many years, as Cuban theatre still does; despite severely limiting artistic freedom, most communist regimes did actually make the arts thrive with subsidies)

- Education (despite the heavy dose of propaganda in schools, almost all communist regimes have massively improved their populations' literacy rates, and have invested heavily in more schools and universities, and in universal access to them)

- Infrastructure (for example, the USSR built an impressive railway network, a glorious metro in Moscow, and numerous power stations, although not all of amazing quality; and PR China has built an excellent highway network, among many other things)

- Womens' rights (the USSR strongly promoted women in the workforce, as does China and Cuba; the Soviet Union was also a pioneer in legalised abortion)

- Industrialisation (putting aside for a moment the enormous sacrifices made to achieve it, the fact is that the USSR, China, and Vietnam transformed rapidly from agrarian economies into industrial powerhouses under communism, and they remain world industrial heavyweights today)

Failure:

- Health care in general (Soviet health care was particularly infamous for its appalling state, and apparently not much has changed in Russia today; China's public health care system is generally considered adequate, but it's hardly an exemplary model either)

- Housing (for the vast majority, Soviet housing and Mao-era Chinese housing were of terrible quality, were overcrowded, and suffered from chronic shortages, and it continues to be this way in Cuba; although the Soviet residences can't be all bad, because Russians are now protesting their demolition)

- Environment (communist regimes, especially the USSR and PR China, have been directly responsible for some of the world's worst environmental catastrophes, the effects of which are expected to linger on for centuries)

- Food security (the communist practice of collectivisation of agriculture has almost always had disastrous results – the USSR experienced food shortages throughout its existence, Maoist China suffered one of the worst famines in human history, and North Korea has endured such acute food scarcity that its population has on occasion resorted to cannibalism)

- Freedom (all communist states so far in history have been totalitarian regimes, and have severely curtailed all freedoms – of speech, of movement, of artistic expression, of religion – and that oppressive legacy lives on to this day)

- Culture and heritage (communist regimes have waged war against their peoples' traditions, religions, and icons, and they have also physically destroyed numerous historic artifacts and monuments; this has resulted in cultural vacuums that may never fully heal)

- Propaganda (truth has invariably taken a back seat to propaganda in communist states – supposedly, the government is perfect, foreign powers are evil, and history can be re-written)

- Corruption (far from the Marxist ideal of universal equality, it has most definitely been a case of some are more equal than others in communist states – communism has engendered endemic bribery and nepotism every time)

- Morale (as the old communist joke goes: "we pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us" – nobody has any motivation to work hard, so productivity nationwide plummets; as well as work morale, the oppressive atmosphere of communist regimes has resulted in ongoing social malaise – modern Russia, for example, has one of the world's highest alcoholism and suicide rates)

- Human damage (rather than making everyone a winner, communism has generally made almost everyone a victim – as well as the huge number of people murdered, imprisoned, and tortured as enemies of a communist state, almost all citizens other than Party elites have endured prolonged suffering due to the states' constant intrusion into their lives)

Image source: FunnyJunk.

Closing remarks

Personally, I have always considered myself quite a "leftie": I'm a supporter of socially progressive causes, and in particular, I've always been involved with environmental movements. However, I've never considered myself a socialist or a communist, and I hope that this brief article on communism reflects what I believe are my fairly balanced and objective views on the topic.

Based on my list of pros and cons above, I would quite strongly tend to conclude that, overall, the communism experiment of the 20th century was not successful at improving the economic, political, and cultural conditions of the populations that experienced it.

I'm reluctant to draw comparisons, because I feel that it's a case of apples and oranges, and also because I feel that a pure analysis should judge communist regimes on their merits and faults, and on theirs alone. However, the fact is that, based on the items in my lists above, much more success has been achieved, and much less failure has occurred, in capitalist democracies, than has been the case in communist states (and the pinnacle has really been achieved in the world's socialist democracies). The Nordic Model – and indeed the model of my own home country, Australia – demonstrates that a high quality of life and a high level of equality are attainable without going down the path of Marxist Communism; indeed, arguably those things are attainable only if Marxist Communism is avoided.

I hope you appreciate what I have endeavoured to do in this article: that is, to avoid the question of whether or not communist theory is fundamentally flawed; to avoid a religious rant about the "evils" of communism or of capitalism; and to avoid judging communism based on its means, and to instead concentrate on what ends it achieved. And I humbly hope that I have stuck to that plan laudably. Because if one thing is needed more than anything else in the arena of analyses of communism, it's clear-sightedness, and a focus on the hard facts, rather than religious zeal and ideological ranting.

]]>

Image source: Day of the Robot.

Most discussion of late seems to treat this encroaching joblessness entirely as an economic issue. Families without incomes, spiralling wealth inequality, broken taxation mechanisms. And, consequently, the solutions being proposed are mainly economic ones. For example, a Universal Basic Income to help everyone make ends meet. However, in my opinion, those economic issues are actually relatively easy to address, and as a matter of sheer necessity we will sort them out sooner or later, via a UBI or via whatever else fits the bill.

The more pertinent issue is actually a social and a psychological one. Namely: how will people keep themselves occupied in such a world? How will people nourish their ambitions, feel that they have a purpose in life, and feel that they make a valuable contribution to society? How will we prevent the malaise of despair, depression, and crime from engulfing those who lack gainful enterprise? To borrow the colourful analogy that others have penned: assuming that there's food on the table either way, how do we head towards a Star Trek rather than a Mad Max future?

Keep busy

The truth is, since the Industrial Revolution, an ever-expanding number of people haven't really needed to work anyway. What I mean by that is: if you think about what jobs are actually about providing society with the essentials such as food, water, shelter, and clothing, you'll quickly realise that fewer people than ever are employed in such jobs. My own occupation, web developer, is certainly not essential to the ongoing survival of society as a whole. Plenty of other occupations, particularly in the services industry, are similarly remote from humanity's basic needs.

So why do these jobs exist? First and foremost, demand. We live in a world of free markets and capitalism. So, if enough people decide that they want web apps, and those people have the money to make it happen, then that's all that's required for "web developer" to become and to remain a viable occupation. Second, opportunity. It needs to be possible to do that thing known as "developing web apps" in the first place. In many cases, the opportunity exists because of new technology; in my case, the Internet. And third, ambition. People need to have a passion for what they do. This means that, ideally, people get to choose an occupation of their own free will, rather than being forced into a certain occupation by their family or by the government. If a person has a natural talent for his or her job, and if a person has a desire to do the job well, then that benefits the profession as a whole, and, in turn, all of society.

Those are the practical mechanisms through which people end up spending much of their waking life at work. However, there's another dimension to all this, too. It is very much in the interest of everyone that makes up "the status quo" – i.e. politicians, the police, the military, heads of big business, and to some extent all other "well to-do citizens" – that most of society is caught up in the cycle of work. That's because keeping people busy at work is the most effective way of maintaining basic law and order, and of enforcing control over the masses. We have seen throughout history that large-scale unemployment leads to crime, to delinquency and, ultimately, to anarchy. Traditionally, unemployment directly results in poverty, which in turn directly results in hunger. But even if the unemployed get their daily bread – even if the crisis doesn't reach let them eat cake proportions – they are still at risk of falling to the underbelly of society, if for no other reason, simply due to boredom.

So, assuming that a significantly higher number of working-age men and women will have significantly fewer job prospects in the immediate future, what are we to do with them? How will they keep themselves occupied?

The Games

I propose that, as an alternative to traditional employment, these people engage in large-scale, long-term, government-sponsored, semi-recreational activities. These must be activities that: (a) provide some financial reward to participants; (b) promote physical health and social well-being; and (c) make a tangible positive contribution to society. As a massive tongue-in-cheek, I call this proposal "The Jobless Games".

My prime candidate for such an activity would be a long-distance walk. The journey could take weeks, months, even years. Participants could number in the hundreds, in the thousands, even in the millions. As part of the walk, participants could do something useful, too; for example, transport non-urgent goods or mail, thus delivering things that are actually needed by others, and thus competing with traditional freight services. Walking has obvious physical benefits, and it's one of the most social things you can do while moving and being active. Such a journey could also be done by bicycle, on horseback, or in a variety of other modes.

Image source: The New Paper.

Other recreational programs could cover the more adventurous activities, such as climbing, rafting, and sailing. However, these would be less suitable, because: they're far less inclusive of people of all ages and abilities; they require a specific climate and geography; they're expensive in terms of equipment and expertise; they're harder to tie in with some tangible positive end result; they're impractical in very large groups; and they damage the environment if conducted on too large a scale.

What I'm proposing is not competitive sport. These would not be races. I don't see what having winners and losers in such events would achieve. What I am proposing is that people be paid to participate in these events, out of the pocket of whoever has the money, i.e. governments and big business. The conditions would be simple: keep up with the group, and behave yourself, and you keep getting paid.

I see such activities co-existing alongside whatever traditional employment is still available in future; and despite all the doom and gloom predictions, the truth is that there always has been real work out there, and there always will be. My proposal is that, same as always, traditional employment pays best, and thus traditional employment will continue to be the most attractive option for how to spend one's days. Following that, "The Games" pay enough to get by on, but probably not enough to enjoy all life's luxuries. And, lastly, as is already the case in most first-world countries today, for the unemployed there should exist a social security payment, and it should pay enough to cover life's essentials, but no more than that. We already pay people sit down money; how about a somewhat more generous payment of stand up money?

Along with these recreational activities that I've described, I think it would also be a good idea to pay people for a lot of the work that is currently done by volunteers without financial reward. In a future with less jobs, anyone who decides to peel potatoes in a soup kitchen, or to host bingo games in a nursing home, or to take disabled people out for a picnic, should be able to support him- or herself and to live in a dignified manner. However, as with traditional employment, there are also only so many "volunteer" positions that need filling, and even with that sector significantly expanded, there would still be many people left twiddling their thumbs. Which is why I think we need some other solution, that will easily and effectively get large numbers of people on their feet. And what better way to get them on their feet, than to say: take a walk!

Large-scale, long-distance walks could also solve some other problems that we face at present. For example, getting a whole lot of people out of our biggest and most crowded cities, and "going on tour" to some of our smallest and most neglected towns, would provide a welcome economic boost to rural areas, considering all the support services that such activities would require; while at the same time, it would ease the crowding in the cities, and it might even alleviate the problem of housing affordability, which is acute in Australia and elsewhere. Long-distance walks in many parts of the world – particularly in Europe – could also provide great opportunities for an interchange of language and culture.

In summary

There you have it, my humble suggestion to help fill the void in peoples' lives in the future. There are plenty of other things that we could start paying people to do, that are more intellectual and that make a more tangible contribution to society: e.g. create art, be spiritual, and perform in music and drama shows. However, these things are too controversial for the government to support on such a large scale, and their benefit is a matter of opinion. I really think that, if something like this is to have a chance of succeeding, it needs to be dead simple and completely uncontroversial. And what could be simpler than walking?

Whatever solutions we come up with, I really think that we need to start examining the issue of 21st-century job redundancy from this social angle. The economic angle is a valid one too, but it has already been analysed quite thoroughly, and it will sort itself out with a bit of ingenuity. What we need to start asking now is: for those young, fit, ambitious people of the future that lack job prospects, what activity can they do that is simple, social, healthy, inclusive, low-impact, low-cost, and universal? I'd love to hear any further suggestions you may have.

]]>Company rule, and the subsequent rule of the British Raj, are also acknowledged as contributing positively to the shaping of Modern India, having introduced the English language, built the railways, and established political and military unity. But these are overshadowed by its legacy of corporate greed and wholesale plunder, which continues to haunt the region to this day.

I recently read Four Heroes of India (1898), by F.M. Holmes, an antique book that paints a rose-coloured picture of Company (and later British Government) rule on the Subcontinent. To the modern reader, the book is so incredibly biased in favour of British colonialism that it would be hilarious, were it not so alarming. Holmes's four heroes were notable military and government figures of 18th and 19th century British India.

Image source: eBay.

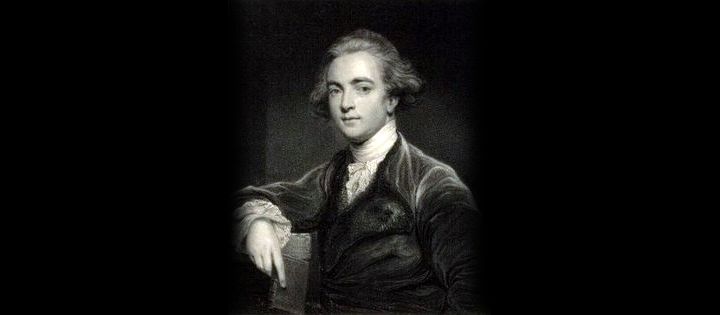

I'd like to present here four alternative heroes: men (yes, sorry, still all men!) who in my opinion represented the British far more nobly, and who left a far more worthwhile legacy in India. All four of these figures were founders or early members of The Asiatic Society (of Bengal), and all were pioneering academics who contributed to linguistics, science, and literature in the context of South Asian studies.

William Jones

The first of these four personalities was by far the most famous and influential. Sir William Jones was truly a giant of his era. The man was nothing short of a prodigy in the field of philology (which is arguably the pre-modern equivalent of linguistics). During his productive life, Jones is believed to have become proficient in no less than 28 languages, making him quite the polyglot:

Eight languages studied critically: English, Latin, French, Italian, Greek, Arabic, Persian, Sanscrit [sic]. Eight studied less perfectly, but all intelligible with a dictionary: Spanish, Portuguese, German, Runick [sic], Hebrew, Bengali, Hindi, Turkish. Twelve studied least perfectly, but all attainable: Tibetian [sic], Pâli [sic], Pahlavi, Deri …, Russian, Syriac, Ethiopic, Coptic, Welsh, Swedish, Dutch, Chinese. Twenty-eight languages.

Source: Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Correspondence, of Sir William Jones, John Shore Baron Teignmouth, 1806, Page 376.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Jones is most famous in scholarly history for being the person who first proposed the linguistic family of Indo-European languages, and thus for being one of the fathers of comparative linguistics. His work laid the foundations for the theory of a Proto-Indo-European mother tongue, which was researched in-depth by later linguists, and which is widely accepted to this day as being a language that existed and that had a sizeable native speaker population (despite there being no concrete evidence for it).

Jones spent 10 years in India, working in Calcutta as a judge. During this time, he founded The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Jones was the foremost of a loosely-connected group of British gentlemen who called themselves orientalists. (At that time, "oriental studies" referred primarily to India and Persia, rather than to China and her neighbours as it does today.)

Like his peers in the Society, Jones was a prolific translator. He produced the authoritative English translation of numerous important Sanskrit documents, including Manu Smriti (Laws of Manu), and Abhiknana Shakuntala. In the field of his "day job" (law), he established the right of Indian citizens to trial by jury under Indian jurisprudence. Plus, in his spare time, he studied Hindu astronomy, botany, and literature.

James Prinsep

The numismatist James Prinsep, who worked at the Benares (Varanasi) and Calcutta mints in India for nearly 20 years, was another of the notable British orientalists of the Company era. Although not quite in Jones's league, he was nevertheless an intelligent man who made valuable contributions to academia. His life was also unfortunately short: he died at the age of 40, after falling sick of an unknown illness and failing to recover.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Prinsep was the founding editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He is best remembered as the pioneer of numismatics (the study of coins) on the Indian Subcontinent: in particular, he studied numerous coins of ancient Bactrian and Kushan origin. Prinsep also worked on deciphering the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts; and he contributed to the science of meteorology.

Charles Wilkins

The typographer Sir Charles Wilkins arrived in India in 1770, several years before Jones and most of the other orientalists. He is considered the first British person in Company India to have mastered the Sanskrit language. Wilkins is best remembered as having created the world's first Bengali typeface, which became a necessity when he was charged with printing the important text A Grammar of the Bengal Language (the first book written in Bengali to ever be printed), written by fellow orientalist Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, and more-or-less commissioned by Governor Warren Hastings.

It should come as no surprise that this pioneering man was one of the founders of The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Like many of his colleagues, Wilkins left a proud legacy as a translator: he was the first person to translate into English the Bhagavad Gita, the most revered holy text in all of Hindu lore. He was also the first director of the "India Office Library".

H. H. Wilson

The doctor Horace Hayman Wilson was in India slightly later than the other gentlemen listed here, not having arrived in India (as a surgeon) until 1808. Wilson was, for a part of his time in Company India, honoured with the role of Secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Wilson was one of the key people to continue Jones's great endeavour of bridging the gap between English and Sanskrit. His key contribution was writing the world's first comprehensive Sanskrit-English dictionary. He also translated the Meghaduuta into English. In his capacity as a doctor, he researched and published on the matter of traditional Indian medical practices. He also advocated for the continued use of local languages (rather than of English) for instruction in Indian native schools.

The legacy

There you have it: my humble short-list of four men who represent the better side of the British presence in Company India. These men, and other orientalists like them, are by no means perfect, either. They too participated in the Company's exploitative regime. They too were part of the ruling elite. They were no Mother Teresa (the main thing they shared in common with her was geographical location). They did little to help the day-to-day lives of ordinary Indians living in poverty.

Nevertheless, they spent their time in India focused on what I believe were noble endeavours; at least, far nobler than the purely military and economic pursuits of many of their peers. Their official vocations were in administration and business enterprise, but they chose to devote themselves as much as possible to academia. Their contributions to the field of language, in particular – under that title I include philology, literature, and translation – were of long-lasting value not just to European gentlemen, but also to the educational foundations of modern India.

In recent times, the term orientalism has come to be synonymous with imperialism and racism (particularly in the context of the Middle East, not so much for South Asia). And it is argued that the orientalists of British India were primarily concerned with strengthening Company rule by extracting knowledge, rather than with truly embracing or respecting India's cultural richness. I would argue that, for the orientalists presented here at least, this was not the case: of course they were agents of British interests, but they also genuinely came to respect and admire what they studied in India, rather than being contemptuous of it.

The legacy of British orientalism in India was, in my opinion, one of the better legacies of British India in general. It's widely acknowledged that it had a positive long-term educational and intellectual effect on the Subcontinent. It's also a topic about which there seems to be insufficient material available – particularly regarding the biographical details of individual orientalists, apart from Jones – so I hope this article is useful to anyone seeking further sources.

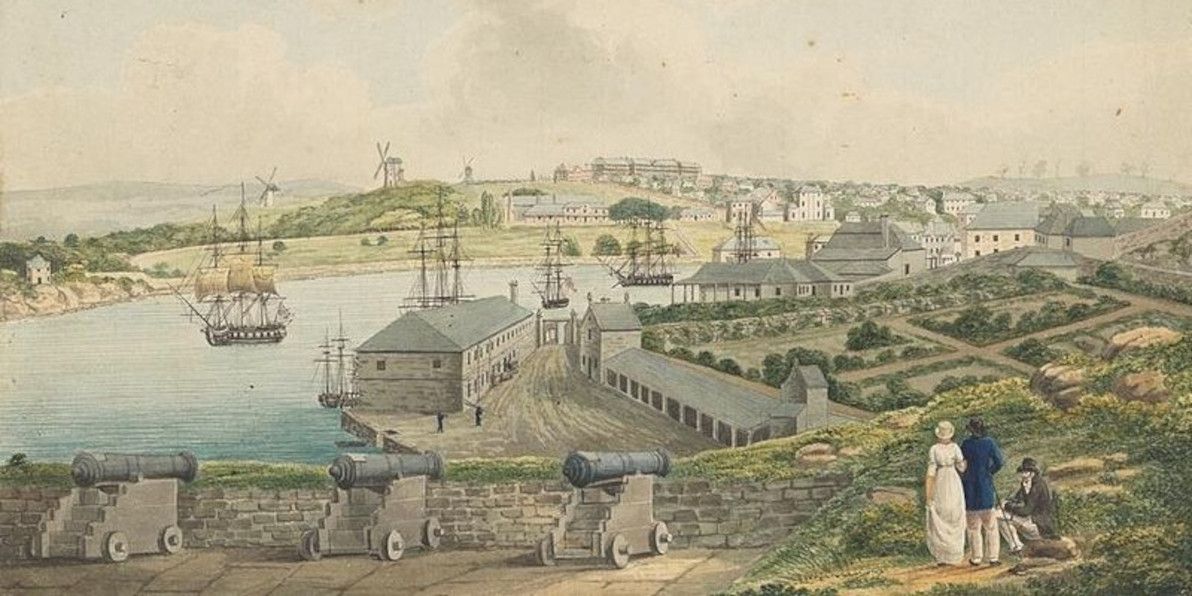

]]>I recently came across a gem of literary work, from the early days of New South Wales: The Present State of Australia, by Robert Dawson. The author spent several years (1826-1828) living in the Port Stephens area (about 200km north of Sydney), as chief agent of the Australian Agricultural Company, where he was tasked with establishing a grazing property. During his time there, Dawson lived side-by-side with the Worimi indigenous peoples, and Worimi anecdotes form a significant part of his book (which, officially, is focused on practical advice for British people considering migration to the Australian frontier).

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

In this article, I'd like to share quite a number of quotes from Dawson's book, which in my opinion may well constitute the oldest known (albeit informal) anthropological study of Indigenous Australians. Considering his rich account of Aboriginal tribal life, I find it surprising that Dawson seems to have been largely forgotten by the history books, and that The Present State of Australia has never been re-published since its first edition in 1830 (the copies produced in 1987 are just fascimiles of the original). I hope that this article serves as a tribute to someone who was an exemplary exception to what was then the norm.

Language

The book includes many passages containing Aboriginal words interspersed with English, as well as English words spelt phonetically (and amusingly) as the tribespeople pronounced them; contemporary Australians should find many of these examples familiar, from the modern-day Aboriginal accents:

Before I left Port Stephens, I intimated to them that I should soon return in a "corbon" (large) ship, with a "murry" (great) plenty of white people, and murry tousand things for them to eat … They promised to get me "murry tousand bark." "Oh! plenty bark, massa." "Plenty black pellow, massa: get plenty bark." "Tree, pour, pive nangry" (three, four, five days) make plenty bark for white pellow, massa." "You come back toon?" "We look out for corbon ship on corbon water," (the sea.) "We tee, (see,) massa." … they sent to inform me that they wished to have a corrobery (dance) if I would allow it.

(page 60)

On occasion, Dawson even goes into grammatical details of the indigenous languages:

"Bael me (I don't) care." The word bael means no, not, or any negative: they frequently say, "Bael we like it;" "Bael dat good;" "Bael me go dere."

(page 65)

It's clear that Dawson himself became quite prolific in the Worimi language, and that – at least for a while – an English-Worimi "creole" emerged as part of white-black dialogue in the Port Stephens area.

Food and water

Although this is probably one of the better-documented Aboriginal traits from the period, I'd also like to note Dawson's accounts of the tribespeoples' fondness for European food, especially for sugar:

They are exceedingly fond of biscuit, bread, or flour, which they knead and bake in the ashes … but the article of food which appears most delicious to them, is the boiled meal of Indian corn; and next to it the corn roasted in the ashes, like chestnuts: of sugar too they are inordinately fond, as well as of everything sweet. One of their greatest treats is to get an Indian bag that has had sugar in it: this they cut into pieces and boil in water. They drink this liquor till they sometimes become intoxicated, and till they are fairly blown out, like an ox in clover, and can take no more.

(page 59)

Dawson also described their manner of eating; his account is not exactly flattering, and he clearly considers this behaviour to be "savage":

The natives always eat (when allowed to do so) till they can go on no longer: they then usually fall asleep on the spot, leaving the remainder of the kangaroo before the fire, to keep it warm. Whenever they awake, which is generally three or four times during the night, they begin eating again; and as long as any food remains they will never stir from the place, unless forced to do so. I was obliged at last to put a stop, when I could, to this sort of gluttony, finding that it incapacitated them from exerting themselves as they were required to do the following day.

(page 123)

Regarding water, Dawson gave a practical description of the Worimi technique for getting a drink in the bush in dry times (and admits that said technique saved him from being up the creek a few times); now, of course, we know that similar techniques were common for virtually all Aboriginal peoples across Australia:

It sometimes happens, in dry seasons, that water is very scarce, particularly near the shores. In such cases, whenever they find a spring, they scratch a hole with their fingers, (the ground being always sandy near the sea,) and suck the water out of the pool through tufts or whisps of grass, in order to avoid dirt or insects. Often have I witnessed and joined in this, and as often felt indebted to them for their example.

They would walk miles rather than drink bad water. Indeed, they were such excellent judges of water, that I always depended upon their selection when we encamped at a distance from a river, and was never disappointed.

(page 150)

Tools and weapons

In numerous sections, Dawson described various tools that the Aborigines used, and their skill and dexterity in fashioning and maintaining them:

[The old man] scraped the point of his spear, which was at least about eight feet long, with a broken shell, and put it in the fire to harden. Having done this, he drew the spear over the blaze of the fire repeatedly, and then placed it between his teeth, in which position he applied both his hands to straighten it, examining it afterwards with one eye closed, as a carpenter would do his planed work. The dexterous and workmanlike manner in which he performed his task, interested me exceedingly; while the savage appearance and attitude of his body, as he sat on the ground before a blazing fire in the forest, with a black youth seated on either side of him, watching attentively his proceedings, formed as fine a picture of savage life as can be conceived.

(page 16)

To the modern reader such as myself, Dawson's use of language (e.g. "a picture of savage life") invariably gives off a whiff of contempt and "European superiority". Personally, I try to give him the benefit of the doubt, and to brush this off as simply "using the vernacular of the time". In my opinion, this is fair justification for Dawson's manner of writing to some extent; but it also shows that he wasn't completely innocent, either: he too held some of the very views which he criticised in his contemporaries.

The tribespeople also exercised great agility in gathering the raw materials for their tools and shelters:

Before a white man can strip the bark beyond his own height, he is obliged to cut down the tree; but a native can go up the smooth branchless stems of the tallest trees, to any height, by cutting notches in the surface large enough only to place the great toe in, upon which he supports himself, while he strips the bark quite round the tree, in lengths from three to six feet. These form temporary sides and coverings for huts of the best description.

(page 19)

And they were quite dexterous in their crafting of nets and other items:

They [the women] make string out of bark with astonishing facility, and as good as you can get in England, by twisting and rolling it in a curious manner with the palm of the hand on the thigh. With this they make nets … These nets are slung by a string round their forehead, and hang down their backs, and are used like a work-bag or reticule. They contain all the articles they carry about with them, such as fishing hooks made from oyster or pearl shells, broken shells, or pieces of glass, when they can get them, to scrape the spears to a thin and sharp point, with prepared bark for string, gum for gluing different parts of their war and fishing spears, and sometime oysters and fish when they move from the shore to the interior.

(page 67)

Music and dance

Dawson wrote fondly of his being witness to corroborees on several occasions, and he recorded valuable details of the song and dance involved:

A man with a woman or two act as musicians, by striking two sticks together, and singing or bawling a song, which I cannot well describe to you; it is chiefly in half tones, extending sometimes very high and loud, and then descending so low as almost to sink to nothing. The dance is exceedingly amusing, but the movement of the limbs is such as no European could perform: it is more like the limbs of a pasteboard harlequin, when set in motion by a string, than any thing else I can think of. They sometimes changes places from apparently indiscriminate positions, and then fall off in pairs; and after this return, with increasing ardour, in a phalanx of four and five deep, keeping up the harlequin-like motion altogether in the best time possible, and making a noise with their lips like "proo, proo, proo;" which changes successively to grunting, like the kangaroo, of which it is an imitation, and not much unlike that of a pig.

(page 61)

Note Dawson's poetic efforts to bring to life the corroboree in words, with "bawling" sounds, "phalanx" movements, and "harlequin-like motion". Modern-day writers probably wouldn't bother to go to such lengths, instead assuming that their audience is familiar with the sights and sounds in question (at the very least, from TV shows). Dawson, who was writing for a Victorian English audience, didn't enjoy this luxury.

Families

In an era when most "white fellas" in the Colony were irrevocably destroying traditional Aboriginal family ties (a practice that was to continue well into the 20th century), Dawson was appreciating and making note of the finer details that he witnessed:

They are remarkably fond of their children, and when the parents die, the children are adopted by the unmarried men and women, and taken the greatest care of.

(page 68)

He also observed the prevalence of monogamy amongst the tribes he encountered:

The husband and wife are in general remarkably constant to each other, and it rarely happens that they separate after having considered themselves as man and wife; and when an elopement or the stealing of another man's gin [wife] takes place, it creates great, and apparently lasting uneasiness in the husband.

(page 154)

As well as the enduring bonds between parents and children:

The parents retain, as long as they live, an influence over their children, whether married or not – I then asked him the reason of this [separating from his partner], and he informed me his mother did not like her, and that she wanted him to choose a better.

(page 315)

Dawson made note of the good and the bad; in the case of families, he condoned the prevalence of domestic violence towards women in the Aboriginal tribes:

On our first coming here, several instances occurred in our sight of the use of this waddy [club] upon their wives … When the woman sees the blow coming, she sometimes holds her head quietly to receive it, much like Punch and his wife in the puppet-shows; but she screams violently, and cries much, after it has been inflicted. I have seen but few gins [wives] here whose heads do not bear the marks of the most dreadful violence of this kind.

(page 66)

Clothing

Some comical accounts of how the Aborigines took to the idea of clothing in the early days:

They are excessively fond of any part of the dress of white people. Sometimes I see them with an old hat on: sometimes with a pair of old shoes, or only one: frequently with an old jacket and hat, without trowsers: or, in short, with any garment, or piece of a garment, that they can get.

(page 75)

They usually reacted well to gifts of garments:

On the following morning I went on board the schooner, and ordered on shore a tomahawk and a suit of slop clothes, which I had promised to my friend Ben, and in which he was immediately dressed. They consisted of a short blue jacket, a checked shirt, and a pair of dark trowsers. He strutted about in them with an air of good-natured importance, declaring that all the harbour and country adjoining belonged to him. "I tumble down [born] pickaninny [child] here," he said, meaning that he was born there. "Belonging to me all about, massa; pose you tit down here, I gib it to you." "Very well," I said: "I shall sit down here." "Budgeree," (very good,) he replied, "I gib it to you;" and we shook hands in ratification of the friendly treaty.

(page 12)

Death and religion

Yet another topic which was scarcely investigated by Dawson's colonial peers – and which we now know to have been of paramount importance in all Aborigines' belief systems — rituals regarding death and mourning:

… when any of their relations die, they show respect for their memories by plastering their heads and faces all over with pipe-clay, which remains till it falls off of itself. The gins [wives] also burn the front of the thigh severely, and bind the wound up with thin strips of bark. This is putting themselves in mourning. We put on black; they put on white: so that it is black and white in both cases.

(page 74)

The Aborigines that Dawson became acquainted with, were convinced that the European settlers were re-incarnations of their ancestors; this belief was later found to be fairly widespread amongst Australia's indigenous peoples:

I cannot learn, precisely, whether they worship any God or not; but they are firm in their belief that their dead friends go to another country; and that they are turned into white men, and return here again.

(page 74)

Dawson appears to have debated this topic at length with the tribespeople:

"When he [the devil] makes black fellow die," I said, "what becomes of him afterwards?" "Go away Englat," (England,) he answered, "den come back white pellow." This idea is so strongly impressed upon their minds, that when they discover any likeness between a white man and any one of their deceased friends, they exclaim immediately, "Dat black pellow good while ago jump up white pellow, den come back again."

(page 158)

Inter-tribe relations

During his time with the Worimi and other tribes, Dawson observed many of the details of how neighbouring tribes interacted, for example, in the case of inter-tribal marriage:

The blacks generally take their wives from other tribes, and if they can find opportunities they steal them, the consent of the female never being made a question in the business. When the neighbouring tribes happen to be in a state of peace with each other, friendly visits are exchanged, at which times the unmarried females are carried off by either party.

(page 153)

In one chapter, Dawson gives an amusing account of how the Worimi slandered and villainised another tribe (the Myall people), with whom they were on unfriendly terms:

The natives who domesticate themselves amongst the white inhabitants, are aware that we hold cannibalism in abhorrence; and in speaking of their enemies, therefore, to us, they always accuse them of this revolting practice, in order, no doubt, to degrade them as much as possible in our eyes; while the other side, in return, throw back the accusation upon them. I have questioned the natives who were so much with me, in the closest manner upon this subject, and although they persist in its being the practice of their enemies, still they never could name any particular instances within their own knowledge, but always ended by saying: "All black pellow been say so, massa." When I have replied, that Myall black fellows accuse them of it also, the answer has been, "Nebber! nebber black pellow belonging to Port Tebens, (Stephens;) murry [very] corbon [big] lie, massa! Myall black pellows patter (eat) always."

(page 125)

The book also explains that the members of a given tribe generally kept within their own ancestral lands, and that they were reluctant and fearful of too-often making contact with neighbouring tribes:

… the two natives who had accompanied them had become frightened at the idea of meeting strange natives, and had run away from them about the middle of their journey …

(page 24)

Relations with colonists

Throughout the book, general comments are made that insinuate the fault and the aggression in general of "white fella" in the Colony:

The natives are a mild and harmless race of savages; and where any mischief has been done by them, the cause has generally arisen, I believe, in bad treatment by their white neighbours. Short as my residence has been here, I have, perhaps, had more intercourse with these people, and more favourable opportunities of seeing what they really are, than any other person in the colony.

(page 57)

Dawson provides a number of specific examples of white aggression towards the Aborigines:

The natives complained to me frequently, that "white pellow" (white fellows) shot their relations and friends; and showed me many orphans, whose parents had fallen by the hands of white men, near this spot. They pointed out one white man, on his coming to beg some provisions for his party up the river Karuah, who, they said, had killed ten; and the wretch did not deny it, but said he would kill them whenever he could.

(page 58)

Sydney

As a modern-day Sydneysider myself, I had a good chuckle reading Dawson's account of his arrival for the first time in Sydney, in 1826:

There had been no arrival at Sydney before us for three or four months. The inhabitants were, therefore, anxious for news. Parties of ladies and gentlemen were parading on the sides of the hills above us, greeting us every now and then, as we floated on; and as soon as we anchored, (which was on a Sunday,) we were boarded by numbers of apparently respectable people, asking for letters and news, as if we had contained the budget of the whole world.

(page 46)

Image source: Wikipedia.

No arrival in Sydney, from the outside world, for "three or four months"?! Who would have thought that a backwater penal town such as this, would one day become a cosmopolitan world city, that sees a jumbo jet land and take off every 5 minutes, every day of the week? Although, it seems that even back then, Dawson foresaw something of Sydney's future:

On every side of the town [Sydney] houses are being erected on new ground; steam engines and distilleries are at work; so that in a short time a city will rise up in this new world equal to any thing out of Europe, and probably superior to any other which was ever created in the same space of time.

(page 47)

And, even back then, there were some (like Dawson) who preferred to get out of the "rat race" of Sydney town:

Since my arrival I have spent a good deal of time in the woods, or bush, as it is called here. For the last five months I have not entered or even seen a house of any kind. My habitation, when at home, has been a tent; and of course it is no better when in the bush.

(page 48)

Image source: NSW National Parks.

There's still a fair bit of bush all around Sydney; although, sadly, not as much as there was in Dawson's day.

General remarks

Dawson's impression of the Aborigines:

I was much amused at this meeting, and above all delighted at the prompt and generous manner in which this wild and untutored man conducted himself towards his wandering brother. If they be savages, thought I, they are very civil ones; and with kind treatment we have not only nothing to fear, but a good deal to gain from them. I felt an ardent desire to cultivate their acquaintance, and also much satisfaction from the idea that my situation would afford me ample opportunities and means for doing so.

(page 11)

Nomadic nature of the tribes:

When away from this settlement, they appear to have no fixed place of residence, although they have a district of country which they call theirs, and in some part of which they are always to be found. They have not, as far as I can learn, any king or chief.

(page 63)

Tribal punishment:

I have never heard but of one punishment, which is, I believe, inflicted for all offences. It consists in the culprit standing, for a certain time, to defend himself against the spears which any of the assembled multitude think proper to hurl at him. He has a small target [shield] … and the offender protects himself so dexterously by it, as seldom to receive any injury, although instances have occurred of persons being killed.

(page 64)

Generosity of Aborigines (also illustrating their lack of a concept of ownership / personal property):

They are exceedingly kind and generous towards each other: if I give tobacco or any thing else to any man, it is divided with the first he meets without being asked for it.

(page 68)

Ability to count / reckon:

They have no idea of numbers beyond five, which are reckoned by the fingers. When they wish to express a number, they hold up so many fingers: beyond five they say, "murry tousand," (many thousands.)

(page 75)

Protocol for returning travellers in a tribe:

It is not customary with the natives of Australia to shake hands, or to greet each other in any way when they meet. The person who has been absent and returns to his friends, approaches them with a serious countenance. The party who receives him is the first to speak, and the first questions generally are, where have you been? Where did you sleep last night? How many days have you been travelling? What news have you brought? If a member of the tribe has been very long absent, and returns to his family, he stops when he comes within about ten yards of the fire, and then sits down. A present of food, or a pipe of tobacco is sent to him from the nearest relation. This is given and received without any words passing between them, whilst silence prevails amongst the whole family, who appear to receive the returned relative with as much awe as if he had been dead, and it was his spirit which had returned to them. He remains in this position perhaps for half an hour, till he receives a summons to join his family at the fire, and then the above questions are put to him.

(page 132)

Final thoughts

The following pages are not put forth to gratify the vanity of authorship, but with the view of communicating facts where much misrepresentation has existed, and to rescue, as far as I am able, the character of a race of beings (of whom I believe I have seen more than any other European has done) from the gross misrepresentations and unmerited obloquy that has been cast upon them.

(page xiii)

Dawson wasn't exactly modest, in his assertion of being the foremost person in the Colony to make a fair representation of the Aborigines; however, I'd say his assertion is quite accurate. As far as I know, he does stand out as quite a solitary figure for his time, in his efforts to meaningfully engage with the tribes of the greater Sydney region, and to document them in a thorough and (relatively) unprejudiced work of prose.

I would therefore recommend those who would place the Australian natives on the level of brutes, to reflect well on the nature of man in his untutored state in comparison with his more civilized brother, indulging in endless whims and inconsistencies, before they venture to pass a sentence which a little calm consideration may convince them to be unjust.

(page 152)

Dawson's criticism of the prevailing attitudes was scathing, although it was clearly criticism that was ignored and unheeded by his contemporaries.

It is not sufficient merely as a passing traveller to see an aboriginal people in their woods and forests, to form a just estimate of their real character and capabilities … To know them well it is necessary to see much more of them in their native wilds … In this position I believe no man has ever yet been placed, although that in which I stood approached more nearly to it than any other known in that country.

(page 329)

With statements like this, Dawson is inviting his fellow colonists to "go bush" and to become acquainted with an Aboriginal tribe, as he did. From others' accounts of the era, those who followed in his footsteps were few and far between.

I have seen the natives from the coast far south of Sydney, and thence to Morton Bay (sic), comprising a line of coast six or seven hundred miles; and I have also seen them in the interior of Argyleshire and Bathurst, as well as in the districts of the Hawkesbury, Hunter's River, and Port Stephens, and have no reason whatever to doubt that they are all the same people.

(page 336)

So, why has a man and a book with so much to say about early contact with the Aborigines, lain largely forgotten and abandoned by the fickle sands of history? Probably the biggest reason, is that Dawson was just a common man. Sure, he was the first agent of AACo: but he was no intrepid explorer, like Burke and Wills; nor an important governor, like Arthur Phillip or Lachlan Macquarie. While the diaries and letters of bigwigs like these have been studied and re-published constantly, not everyone can enjoy the historical limelight.

No doubt also a key factor, was that Dawson ultimately fell out badly with the powerful Macarthur family, who were effectively his employers during his time in Port Stephens. The Present State of Australia is riddled with thinly veiled slurs at the Macarthurs, and it's quite likely that this guaranteed the book's not being taken seriously by anyone, in the Colony or elsewhere, for a long time.

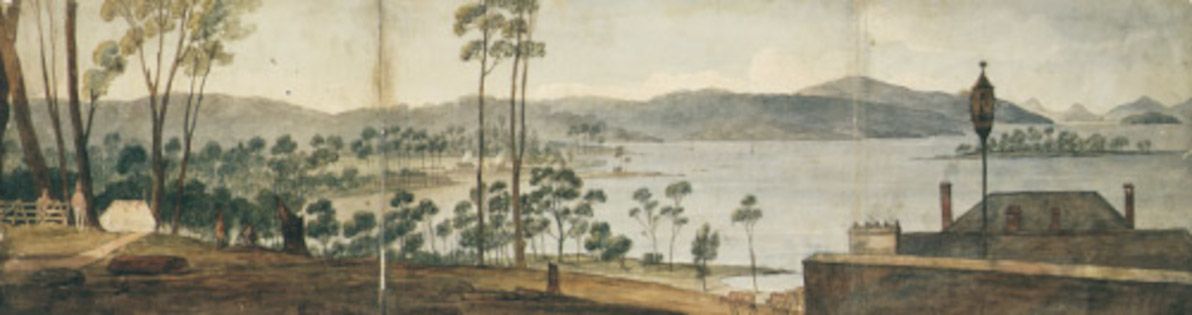

Dawson's work is, in my opinion, an outstanding record of indigenous life in Australia, at a time when the ancient customs and beliefs were still alive and visible throughout most of present-day NSW. It also illustrates the human history of a geographically beautiful region that's quite close to my heart. Like many Sydneysiders, I've spent several summer holidays at Port Stephens during my life. I've also been camping countless times at nearby Myall Lakes; and I have some very dear family friends in Booral, a small town which sits alongside the Karuah River just upstream from Port Stephens (and which also falls within Worimi country).

Image source: State Library of New South Wales.

In leaving as a legacy his narrative of the Worimi people and their neighbours (which is, as far as I know, the only surviving first-hand account of these people from the coloial era of any significance), I believe that Dawson's work should be lauded and celebrated. At a time when the norm for bush settlers was to massacre and to wreak havoc upon indigenous peoples, Dawson instead chose to respect and to make friends with those that he encountered.

Personally, I think the honour of "first anthropologist of the Aborigines" is one that Dawson can rightly claim (although others may feel free to dispute this). Descendants of the Worimi live in the Port Stephens area to this day; and I hope that they appreciate Dawson's tribute, as no doubt the spirits of their ancestors do.

]]>Societal vices have always been bountiful. Back in the ol' days, it was just the usual suspects. War. Violence. Greed. Corruption. Injustice. Propaganda. Lewdness. Alcoholism. To name a few. In today's world, still more scourges have joined in the mix. Consumerism. Drug abuse. Environmental damage. Monolithic bureaucracy. And plenty more.

There always have been some folks who elect to isolate themselves from the masses, to renounce their mainstream-ness, to protect themselves from all that nastiness. And there always will be. Nothing wrong with doing so.

However, there's a difference between protecting oneself from "the evils of society", and blinding oneself to their very existence. Sometimes this difference is a fine line. Particularly in the case of families, where parents choose to shield from the Big Bad World not only themselves, but also their children. Protection is noble and commendable. Blindfolding, in my opinion, is cowardly and futile.

Image source: greenskullz1031 on Photobucket.

Seclusion

There are plenty of examples from bygone times, of historical abstainers from mainstream society. Monks and nuns, who have for millenia sought serenity, spirituality, abstinence, and isolation from the material. Hermits of many varieties: witches, grumpy old men / women, and solitary island-dwellers.

Religion has long been an important motive for seclusion. Many have settled on a reclusive existence as their solution to avoiding widespread evils and being closer to G-d. Other than adult individuals who choose a monastic life, there are also whole communities, composed of families with children, who live in seclusion from the wider world. The Amish in rural USA are probably the most famous example, and also one of the longest-running such communities. Many ultra-orthodox Jewish communities, particularly within present-day Israel, could also be considered as secluded.

Image source: Wikipedia: Amish.

More recently, the "commune living" hippie phenomenon has seen tremendous growth worldwide. The hippie ideology is, of course, generally an anti-religious one, with its acceptance of open relationships, drug use, lack of hierarchy, and often a lack of any formal G-d. However, the secluded lifestyle of hippie communes is actually quite similar to that of secluded religious groups. It's usually characterised by living amidst, and in tune with, nature; rejecting modern technology; and maintaining a physical distance from regular urban areas. The left-leaning members of these communities tend to strongly shun consumerism, and to promote serenity and spirituality, much like their G-d fearing comrades.

In a bubble

Like the members of these communities, I too am repulsed by many of the "evils" within the society in which we live. Indeed, the idea of joining such a community is attractive to me. It would be a pleasure and a relief to shut myself out from the blight that threatens me, and from everyone that's "infected" by it. Life would be simpler, more peaceful, more wholesome.

I empathise with those who have chosen this path in life. Just as it's tempting to succumb to all the world's vices, so too is it tempting to flee from them. However, such people are also living in a bubble. An artificial world, from which the real world has been banished.

What bothers me is not so much the independent adult people who have elected for such an existence. Despite all the faults of the modern world, most of us do at least enjoy far-reaching liberty. So, it's a free land, and adults are free to live as they will, and to blind themselves to what they will.

What does bother me, is that children are born and raised in such an existence. The adult knows what it is that he or she is shut off from, and has experienced it before, and has decided to discontinue experiencing it. The child, on the other hand, has never been exposed to reality, he or she knows only the confines of the bubble. The child is blind, but to what, it knows not.

Image source: CultureLab: Breaking out of the internet filter bubble.

This is a cowardly act on the part of the parents. It's cowardly because a child only develops the ability to combat and to reject the world's vices, such as consumerism or substance abuse, by being exposed to them, by possibly experimenting with them, and by making his or her own decisions. Parents that are serious about protecting their children do expose them to the Big Bad World, they do take risks; but they also do the hard yards in preparing their children for it: they ensure that their children are raised with education, discipline, and love.

Blindfolding children to the reality of wider society is also futile — because, sooner or later, whether still as children or later as adults, the Big Bad World exposes itself to all, whether you like it or not. No Amish countryside, no hippie commune, no far-flung island, is so far or so disconnected from civilisation that its inhabitants can be prevented from ever having contact with it. And when the day of exposure comes, those that have lived in their little bubble find themselves totally unprepared for the very "evils" that they've supposedly been protected from for all their lives.

Keep it balanced

In my opinion, the best way to protect children from the world's vices, is to expose them in moderation to the world's nasty underbelly, while maintaining a stable family unit, setting a strong example of rejecting the bad, and ensuring a solid education. That is, to do what the majority of the world's parents do. That's right: it's a formula that works reasonably well for billions of people, and that has been developed over thousands of years, so there must be some wisdom to it.

Obviously, children need to be protected from dangers that could completely overwhelm them. Bringing up a child in a favela environment is not ideal, and sometimes has horrific consequences, just watch City of G-d if you don't believe me. But then again, blindfolding is the opposite extreme; and one extreme can be as bad as the other. Getting the balance somewhere in between is the key.

]]>There are plenty of articles round and about the interwebz, aimed more at the practical side of coming to Chile: i.e. tips regarding how to get around; lists of rough prices of goods / services; and crash courses in Chilean Spanish. There are also a number of commentaries on the cultural / social differences between Chile and elsewhere – on the national psyche, and on the political / economic situation.

My endeavour is to avoid this article from falling neatly into either of those categories. That is, I'll be covering some eccentricities of Chile that aren't practical tips as such, although knowing about them may come in handy some day; and I'll be covering some anecdotes that certainly reflect on cultural themes, but that don't pretend to paint the Chilean landscape inside-out, either.

Que disfrutiiy, po.

Image sources: Times Journeys / 2GB.

Fin de mes

Here in Chile, all that is money-related is monthly. You pay everything monthly (your rent, all your bills, all membership fees e.g. gym, school / university fees, health / home / car insurance, etc); and you get paid monthly (if you work here, which I don't). I know that Chile isn't the only country with this modus operandi: I believe it's the European system; and as far as I know, it's the system in various other Latin American countries too.

In Australia – and as far as I know, in most English-speaking countries – there are no set-in-stone rules about the frequency with which you pay things, or with which you get paid. Bills / fees can be weekly, monthly, quarterly, annual… whatever (although rent is generally charged and is talked about as a weekly cost). Your pay cheque can be weekly, fortnightly, monthly, quarterly… equally whatever (although we talk about "how much you earn" annually, even though hardly anyone is paid annually). I guess the "all monthly" system is more consistent, and I guess it makes it easier to calculate and compare costs. However, having grown up with the "whatever" system, "all monthly" seems strange and somewhat amusing to me.

In Chile, although payment due dates can be anytime throughout the month, almost everyone receives their salary at fin de mes (the end of the month). I believe the (rough) rule is: the dosh arrives on the actual last day of the month if it's a regular weekday; or the last regular weekday of the month, if the actual last day is a weekend or public holiday (which is quite often, since Chile has a lot of public holidays – twice as many as Australia!).

This system, combined with the last-minute / impulsive form of living here, has an effect that's amusing, frustrating, and (when you think about it) depressingly predictable. As I like to say (in jest, to the locals): in Chile, it's Christmas time every end-of-month! The shops are packed, the restaurants are overflowing, and the traffic is insane, on the last day and the subsequent few days of each month. For the rest of the month, all is quiet. Especially the week before fin de mes, which is really Struggle Street for Chileans. So extreme is this fin de mes culture, that it's even busy at the petrol stations at this time, because many wait for their pay cheque before going to fill up the tank.

This really surprised me during my first few months in Chile. I used to ask: ¿Qué pasa? ¿Hay algo important hoy? ("What's going on? Is something important happening today?"). To which locals would respond: Es fin de mes! Hoy te pagan! ("It's end-of-month! You get paid today!"). These days, I'm more-or-less getting the hang of the cycle; although I don't think I'll ever really get my head around it. I'm pretty sure that, even if we did all get paid on the same day in Australia (which we don't), we wouldn't all rush straight to the shops in a mad stampede, desperate to spend the lot. But hey, that's how life is around here.

Cuotas

Continuing with the socio-economic theme, and also continuing with the "all-monthly" theme: another Chile-ism that will never cease to amuse and amaze me, is the omnipresent cuotas ("monthly instalments"). Chile has seen a spectacular rise in the use of credit cards, over the last few decades. However, the way these credit cards work is somewhat unique, compared with the usual credit system in Australia and elsewhere.

Any time you make a credit card purchase in Chile, the cashier / shop assistant will, without fail, ask you: ¿cuántas cuotas? ("how many instalments?"). If you're using a foreign credit card, like myself, then you must always answer: sin cuotas ("no instalments"). This is because, even if you wanted to pay for your purchase in chunks over the next 3-24 months (and trust me, you don't), you can't, because this system of "choosing at point of purchase to pay in instalments" only works with local Chilean cards.

Chile's current president, the multi-millionaire Sebastian Piñera, played an important part in bringing the credit card to Chile, during his involvement with the banking industry before entering politics. He's also generally regarded as the inventor of the cuotas system. The ability to choose your monthly instalments at point of sale is now supported by all credit cards, all payment machines, all banks, and all credit-accepting retailers nationwide. The system has even spread to some of Chile's neighbours, including Argentina.

Unfortunately, although it seems like something useful for the consumer, the truth is exactly the opposite: the cuotas system and its offspring, the cuotas national psyche, has resulted in the vast majority of Chileans (particularly the less wealthy among them) being permanently and inescapably mired in debt. What's more, although some of the cuotas offered are interest-free (with the most typical being a no-interest 3-instalment plan), some plans and some cards (most notoriously the "department store bank" cards) charge exhorbitantly high interest, and are riddled with unfair and arcane terms and conditions.

Última hora

Chile's a funny place, because it's so "not Latin America" in certain aspects (e.g. much better infrastructure than most of its neighbours), and yet it's so "spot-on Latin America" in other aspects. The última hora ("last-minute") way of living definitely falls within the latter category.

In Chile, people do not make plans in advance. At least, not for anything social- or family-related. Ask someone in Chile: "what are you doing next weekend?" And their answer will probably be: "I don't know, the weekend hasn't arrived yet… we'll see!" If your friends or family want to get together with you in Chile, don't expect a phone call the week before. Expect a phone call about an hour before.

I'm not just talking about casual meet-ups, either. In Chile, expect to be invited to large birthday parties a few hours before. Expect to know what you're doing for Christmas / New Year a few hours before. And even expect to know if you're going on a trip or not, a few hours before (and if it's a multi-day trip, expect to find a place to stay when you arrive, because Chileans aren't big on making reservations).

This is in stark contrast to Australia, where most people have a calendar to organise their personal life (something extremely uncommon in Chile), and where most peoples' evenings and weekends are booked out at least a week or two in advance. Ask someone in Sydney what their schedule is for the next week. The answer will probably be: "well, I've got yoga tomorrow evening, I'm catching up with Steve for lunch on Wednesday, big party with some old friends on Friday night, beach picnic on Saturday afternoon, and a fancy dress party in the city on Saturday night." Plus, ask them what they're doing in two months' time, and they'll probably already have booked: "6 nights staying in a bungalow near Batemans Bay".

The última hora system is both refreshing and frustrating, for a planned-ahead foreigner like myself. It makes you realise just how regimented, inflexible, and lacking in spontenaeity life can be in your home country. But, then again, it also makes you tear your hair out, when people make zero effort to co-ordinate different events and to avoid clashes. Plus, it makes for many an awkward silence when the folks back home ask the question that everybody asks back home, but that nobody asks around here: "so, what are you doing next weekend?" Depends which way the wind blows.

Sit down

In Chile (and elsewhere nearby, e.g. Argentina), you do not eat or drink while standing. In most bars in Chile, everyone is sitting down. In fact, in general there is little or no "bar" area, in bars around here; it's all tables and chairs. If there are no tables or chairs left, people will go to a different bar, or wait for seats to become vacant before eating / drinking. Same applies in the home, in the park, in the garden, or elsewhere: nobody eats or drinks standing up. Not even beer. Not even nuts. Not even potato chips.

In Australia (and in most other English-speaking countries, as far as I know), most people eat and drink while standing, in a range of different contexts. If you're in a crowded bar or pub, eating / drinking / talking while standing is considered normal. Likewise for a big house party. Same deal if you're in the park and you don't want to sit on the grass. I know it's only a little thing; but it's one of those little things that you only realise is different in other cultures, after you've lived somewhere else.

It's also fairly common to see someone eating their take-away or other food while walking, in Australia. Perhaps some hot chips while ambling along the beach. Perhaps a sandwich for lunch while running (late) to a meeting. Or perhaps some lollies on the way to the bus stop. All stuff you wouldn't blink twice at back in Oz. In Chile, that is simply not done. Doesn't matter if you're in a hurry. It couldn't possibly be such a hurry, that you can't sit down to eat in a civilised fashion. The Chilean system is probably better for your digestion! And they have a point: perhaps the solution isn't to save time by eating and walking, but simply to be in less of a hurry?

Image source: Dondequieroir.

Walled and shuttered

One of the most striking visual differences between the Santiago and Sydney streetscapes, in my opinion, is that walled-up and shuttered-up buildings are far more prevalent in the former than in the latter. Santiago is not a dangerous city, by Latin-American or even by most Western standards; however, it often feels much less secure than it should, particularly at night, because often all you can see around you is chains, padlocks, and sturdy grilles. Chileans tend to shut up shop Fort Knox-style.

Walk down Santiago's Ahumada shopping strip in the evening, and none of the shopfronts can be seen. No glass, no lit-up signs, no posters. Just grey steel shutters. Walk down Sydney's Pitt St in the evening, and – even though all the shops close earlier than in Santiago – it doesn't feel like a prison, it just feels like a shopping area after-hours.

In Chile, virtually all houses and apartment buildings are walled and gated. Also, particularly ugly in my opinion, schools in Chile are surrounded by high thick walls. For both houses and schools, it doesn't matter if they're upper- or lower-class, nor what part of town they're in: that's just the way they build them around here. In Australia, on the other hand, you can see most houses and gardens from the street as you go past (and walled-in houses are criticised as being owned by "paranoid people"); same with schools, which tend to be open and abundant spaces, seldom delimiting their boundary with anything more than a low mesh fence.

As I said, Santiago isn't a particularly dangerous city, although it's true that robbery is far more common here than in Sydney. The real difference, in my opinion, is that Chileans simply don't feel safe unless they're walled in and shuttered up. Plus, it's something of a vicious cycle: if everyone else in the city has a wall around their house, and you don't, then chances are that your house will be targeted, not because it's actually easier to break into than the house next door (which has a wall that can be easily jumped over anyway), but simply because it looks more exposed. Anyway, I will continue to argue to Chileans that their country (and the world in general) would be better with less walls and less barriers; and, no doubt, they will continue to stare back at me in bewilderment.

Image source: eszsara (Flickriver).

In summary

So, there you have it: a few of my random observations about life in Santiago, Chile. I hope you've found them educational and entertaining. Overall, I've enjoyed my time in this city; and while I'm sometimes critical of and poke fun at Santiago's (and Chile's) peculiarities, I'm also pretty sure I'll miss then when I'm gone. If you have any conclusions of your own regarding life in this big city, feel free to share them below.

]]>However, I wasn't able to find any articles that specifically investigate the compatibility between the world's major religions. The areas where different religions are "on the same page", and are able to understand each other and (in the better cases) to respect each other; vs the areas where they're on a different wavelength, and where a poor capacity for dialogue is a potential cause for conflict.

I have, therefore, taken the liberty of penning such an analysis myself. What follows is a very humble list of aspects in which the world's major religions are compatible, vs aspects in which they are incompatible.

Compatible:

- Divinity (usually although not universally manifested by the concept of a G-d or G-ds; this is generally a religion's core belief)

- Sanctity (various events, objects, places, and people are considered sacred by the religion)

- Community (the religion is practiced by more than one person; the religion's members assemble in order to perform significant tasks together; the religion has the fundamental properties of a community – i.e. a start date, a founder or founders, a name / label, a size as measured by membership, etc)

- Personal communication with the divine and/or personal expression of spirituality (almost universally manifested in the acts of prayer and/or meditation)

- Stories (mythology, stories of the religion's origins / founding, parables, etc)

- Membership and initiation (i.e. a definition of "who is a member" of the religion, and defined methods of obtaining membership – e.g. by birth, by initiation ritual, by force)

- Death rites (handling of dead bodies – e.g. burial, cremation; mourning rituals; belief in / position regarding one's fate following death)

- Material expression, often (although not always) involving symbolism (e.g. characteristic clothing, music, architecture, and artwork)

- Ethical guidance (in the form of books, oral wisdom, fundamental precepts, laws, codes of conduct, etc – although it should also be noted that religion and ethics are two different concepts)

- Social guidance (marriage and family; celebration of festivities and special occasions; political views; behaviour towards various societal groups e.g. children, elders, community leaders, disadvantaged persons, members of other religions)

- Right and wrong, in terms of actions and/or thoughts (i.e. definition of "good deeds", and of "sins"; although the many connotations of sin – e.g. punishment, divine judgment, consequences in the afterlife – are not universal)

- Common purpose (although it's impossible to definitively state what religion's purpose is – e.g. religion provides hope; "religion's purpose is to provide a sense of purpose"; religion provides access to the spiritual and the divine; religion exists to facilitate love and compassion – also plenty of sceptical opinions, e.g. religion is the "opium of the masses"; religion is superstition and dogma for fools)

- Explanation of the unknown (religion provides answers where reason and science cannot – e.g. creation, afterlife)

Incompatible:

- The nature of divinity (one G-d vs many G-ds; G-d-like personification of divinity vs more abstract concept of a divine force / divine plane of existence; infinite vs constrained extent of divine power)

- Acknowledgement of other religions (not all religions even acknowledge the existence of others; of those that do, many refuse to acknowledge their validity; and of those that acknowledge validity, most consider other religions as "inferior")

- Tolerance of other religions (while some religions encourage harmony with the rest of the world, other religions promote various degrees of intolerance – e.g. holy war, forced conversion, socio-economic discrimination)

- Community structure (religious communities range from strict bureaucratic hierarchies, to unstructured liberal movements, with every possible shade of grey in between)

- What has a "soul" (all objects in the universe, from rocks upward, have a soul; vs only living organisms have a soul; vs only humans have a soul; vs there is no such thing as a soul)

- Afterlife (re-incarnation vs eternal afterlife vs soul dies with body; consequences, if any, of behaviour in life on what happens after death)

- Acceptable social norms (monogamous vs polygamous marriage; fidelity vs open relationships; punishment vs leniency towards children; types of prohibited relationships)

- Form of rules (strict laws with strict punishments; vs only general guidelines / principles)

- Ethical stances (on a broad range of issues, e.g. abortion, drug use, homosexuality, tattoos / piercings, blood transfusions, organ donation)

- Leader figure(s) (Christ vs Moses vs Mohammed vs Buddha vs saints vs pagan deities vs Confucius)

- Holy texts (Qu'ran vs Bible vs Torah vs Bhagavad Gita vs Tripitaka)

- Ritual manifestations (differences in festivals; feasting vs fasting vs dietary laws; song, dance, clothing, architecture)

Why can't we be friends?

This quick article is my take on the age-old question: if all religions are supposedly based on universal peace and love, then why have they caused more war and bloodshed than any other force in history?

My logic behind comparing religions specifically in terms of "compatibility", rather than simply in terms of "similarities and differences", is that a compatibility analysis should yield conclusions that are directly relevant to the question that we're all asking (i.e. Why can't we be friends?). Logically, if religions were all 100% compatible with each other, then they'd never have caused any conflict in all of human history. So where, then, are all those pesky incompatibilities, that have caused peace-avowing religions to time and again be at each others' throats?

The answer, I believe, is the same one that explains why Java and FORTRAN don't get along well (excuse the geek reference). They both let you write computer programs – but on very different hardware, and in very different coding styles. Or why Chopin fans and Rage Against the Machine fans aren't best friends. They both like to listen to music, but at very different decibels, and with very different amounts of tattoos and piercings applied. Or why a Gemini and a Cancer weren't meant for each other (if you happen to believe in astrology, which I don't). They're both looking for companionship in this big and lonely world, but they laugh and cry in different ways, and the fact is they'll just never agree on whether sushi should be eaten with a fork or with chopsticks.

Religions are just one more parallel. They all aim to bring purpose and hope to one's life; but they don't always quite get there, because along the way they somehow manage to get bogged down discussing on which day of the week only raspberry yoghurt should be eaten, or whether the gates of heaven are opened by a lifetime of charitable deeds or by just ringing the buzzer.