I was also surprised to learn, after doing a modest bit of research, that Tolstoy is seldom mentioned amongst any of the prominent figures in philosophy or metaphysics over the past several centuries. The only articles that even deign to label Tolstoy as a philosopher, are ones that are actually more concerned with Tolstoy as a cult-inspirer, as a pacifist, and as an anarchist.

So, while history has been just and generous in venerating Tolstoy as a novelist, I feel that his contribution to the field of philosophy has gone unacknowledged. This is no doubt in part because Tolstoy didn't consider himself a philosopher, and because he didn't pen any purely philosophical works (published separately from novels and other works), and because he himself criticised the value of such works. Nevertheless, I feel warranted in asking: is Tolstoy a forgotten philosopher?

Image source: Waymarking

Free will in War and Peace

The concept of free will that Tolstoy articulates in War and Peace (particularly in the second epilogue), in a nutshell, is that there are two forces that influence every decision at every moment of a person's life. The first, free will, is what resides within a person's mind (and/or soul), and is what drives him/her to act per his/her wishes. The second, necessity, is everything that resides external to a person's mind / soul (that is, a person's body is also for the most part considered external), and is what strips him/her of choices, and compels him/her to act in conformance with the surrounding environment.

Whatever presentation of the activity of many men or of an individual we may consider, we always regard it as the result partly of man's free will and partly of the law of inevitability.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

A simple example that would appear to demonstrate acting completely according to free will: say you're in an ice cream parlour (with some friends), and you're tossing up between getting chocolate or hazelnut. There's no obvious reason why you would need to eat one flavour vs another. You're partial to both. They're both equally filling, equally refreshing, and equally (un)healthy. You'll be able to enjoy an ice cream with your friends regardless. You're free to choose!

You say: I am not and am not free. But I have lifted my hand and let it fall. Everyone understands that this illogical reply is an irrefutable demonstration of freedom.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter VIII

And another simple example that would appear to demonstrate being completely overwhelmed by necessity: say there's a gigantic asteroid on a collision course for Earth. It's already entered the atmosphere. You're looking out your window and can see it approaching. It's only seconds until it hits. There's no obvious choice you can make. You and all of humanity are going to die very soon. There's nothing you can do!

A sinking man who clutches at another and drowns him; or a hungry mother exhausted by feeding her baby, who steals some food; or a man trained to discipline who on duty at the word of command kills a defenseless man – seem less guilty, that is, less free and more subject to the law of necessity, to one who knows the circumstances in which these people were placed …

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

However, the main point that Tolstoy makes regarding these two forces, is that neither of them does – and indeed, neither of them can – ever exist in absolute form, in the universe as we know it. That is to say, a person is never (and can never be) free to decide anything 100% per his/her wishes; and likewise, a person is never (and can never be) shackled such that he/she is 100% compelled to act under the coercion of external agents. It's a spectrum! And every decision, at every moment of a person's life (and yes, every moment of a person's life involves a decision), lies somewhere on that spectrum. Some decisions are made more freely, others are more constrained. But all decisions result from a mix of the two forces.

In neither case – however we may change our point of view, however plain we may make to ourselves the connection between the man and the external world, however inaccessible it may be to us, however long or short the period of time, however intelligible or incomprehensible the causes of the action may be – can we ever conceive either complete freedom or complete necessity.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter X

So, going back to the first example: there are always some external considerations. Perhaps there's a little bit more chocolate than hazelnut in the tubs, so you'll feel just that little bit guilty if you choose the hazelnut, that you'll be responsible for the parlour running out of it, and for somebody else missing out later. Perhaps there's a deal that if you get exactly the same ice cream five times, you get a sixth one free, and you've already ordered chocolate four times before, so you feel compelled to order it again this time. Or perhaps you don't really want an ice cream at all today, but you feel that peer pressure compels you to get one. You're not completely free after all!

If we consider a man alone, apart from his relation to everything around him, each action of his seems to us free. But if we see his relation to anything around him, if we see his connection with anything whatever – with a man who speaks to him, a book he reads, the work on which he is engaged, even with the air he breathes or the light that falls on the things about him – we see that each of these circumstances has an influence on him and controls at least some side of his activity. And the more we perceive of these influences the more our conception of his freedom diminishes and the more our conception of the necessity that weighs on him increases.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

And, going back to the second example: you always have some control over your own destiny. You have but a few seconds to live. Do you cower in fear, flat on the floor? Do you cling to your loved one at your side? Do you grab a steak knife and hurl it defiantly out the window at the approaching asteroid? Or do you stand there, frozen to the spot, staring awestruck at the vehicle of your impending doom? It may seem pointless, weighing up these alternatives, when you and your whole world are about to be pulverised; but aren't your last moments in life, especially if they're desperate last moments, the ones by which you'll be remembered? And how do you know for certain that there will be nobody left to remember you (and does that matter anyway)? You're not completely bereft of choices after all!

… even if, admitting the remaining minimum of freedom to equal zero, we assumed in some given case – as for instance in that of a dying man, an unborn babe, or an idiot – complete absence of freedom, by so doing we should destroy the very conception of man in the case we are examining, for as soon as there is no freedom there is also no man. And so the conception of the action of a man subject solely to the law of inevitability without any element of freedom is just as impossible as the conception of a man's completely free action.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter X

Background story

Tolstoy's philosophical propositions in War and Peace were heavily influenced by the ideas of one of his contemporaries, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. In later years, Tolstoy candidly expressed his admiration for Schopenhauer, and he even went so far as to assert that, philosophically speaking, War and Peace was a repetition of Schopenhauer's seminal work The World as Will and Representation.

Schopenhauer's key idea, was that the whole universe (at least, as far as any one person is concerned) consists of two things: the will, which doesn't exist in physical form, but which is the essence of a person, and which contains all of one's drives and desires; and the representation, which is a person's mental model of all that he/she has sensed and interacted with in the physical realm. However, rather than describing the will as the engine of one's freedom, Schopenhauer argues that one is enslaved by the desires imbued in his/her will, and that one is liberated from the will (albeit only temporarily) by aesthetic experience.

Image source: 9gag

Schopenhauer's theories were, in turn, directly influenced by those of Immanuel Kant, who came a generation before him, and who is generally considered the greatest philosopher of the modern era. Kant's ideas (and his works) were many (and I have already written about Kant's ideas recently), but the one of chief concern here – as expounded primarily in his Critique of Pure Reason – was that there are two realms in the universe: the phenomenal, that is, the physical, the universe as we experience and understand it; and the noumenal, that is, a theoretical non-material realm where everything exists as a "thing-in-itself", and about which we know nothing, except for what we are able to deduce via practical reason. Kant argued that the phenomenal realm is governed by absolute causality (that is, by necessity), but that in the noumenal realm there exists absolute free will; and that the fact that a person exists in both realms simultaneously, is what gives meaning to one's decisions, and what makes them able to be measured and judged in terms of ethics.

We can trace the study of free will further through history, from Kant, back to Hume, to Locke, to Descartes, to Augustine, and ultimately back to Plato. In the writings of all these fine folks, over the millennia, there can be found common concepts such as a material vs an ideal realm, a chain of causation, and a free inner essence. The analysis has become ever more refined with each passing generation of metaphysics scholars, but ultimately, it has deviated very little from its roots in ancient times.

It's unique

There are certainly parallels between Tolstoy's War and Peace, and Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation (and, in turn, with other preceding works), but I for one disagree that the former is a mere regurgitation of the latter. Tolstoy is selling himself short. His theory of free will vs necessity is distinct from that of Schopenhauer (and from that of Kant, for that matter). And the way he explains his theory – in terms of a "spectrum of free-ness" – is original as far as I'm aware, and is laudable, if for no other reason, simply because of how clear and easy-to-grok it is.

It should be noted, too, that Tolstoy's philosophical views continued to evolve significantly, later in his life, years after writing War and Peace. At the dawn of the 1900s (by which time he was an old man), Tolstoy was best known for having established his own "rational" version of Christianity, which rejected all the rituals and sacraments of the Orthodox Church, and which gained a cult-like following. He also adopted the lifestyle choices – extremely radical at the time – of becoming vegetarian, of renouncing violence, and of living and dressing like a peasant.

Image source: Flickr

War and Peace is many things. It's an account of the Napoleonic Wars, its bloody battles, its geopolitik, and its tremendous human cost. It's a nostalgic illustration of the old Russian aristocracy – a world long gone – replete with lavish soirees, mountains of servants, and family alliances forged by marriage. And it's a tenderly woven tapestry of the lives of the main protagonists – their yearnings, their liveliest joys, and their deepest sorrows – over the course of two decades. It rightly deserves the praise that it routinely receives, for all those elements that make it a classic novel. But it also deserves recognition for the philosophical argument that Tolstoy peppers throughout the text, and which he dedicates the final pages of the book to making more fully fledged.

]]>However, as anyone exposed to the industry knows, the current state-of-the-art is still plagued by fundamental shortcomings. In a nutshell, the current generation of AI is characterised by big data (i.e. a huge amount of sample data is needed in order to yield only moderately useful results), big hardware (i.e. a giant amount of clustered compute resources is needed, again in order to yield only moderately useful results), and flawed algorithms (i.e. algorithms that, at the end of the day, are based on statistical analysis and not much else – this includes the latest Convolutional Neural Networks). As such, the areas of success (impressive though they may be) are still dwarfed by the relative failures, in areas such as natural language conversation, criminal justice assessment, and art analysis / art production.

In my opinion, if we are to have any chance of reaching a higher plane of AI – one that demonstrates more human-like intelligence – then we must lessen our focus on statistics, mathematics, and neurobiology. Instead, we must turn our attention to philosophy, an area that has traditionally been neglected by AI research. Only philosophy (specifically, metaphysics and epistemology) contains the teachings that we so desperately need, regarding what "reasoning" means, what is the abstract machinery that makes reasoning possible, and what are the absolute limits of reasoning and knowledge.

What is reason?

There are many competing theories of reason, but the one that I will be primarily relying on, for the rest of this article, is that which was expounded by 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason and other texts. Not everyone agrees with Kant, however his is generally considered the go-to doctrine, if for no other reason (no pun intended), simply because nobody else's theories even come close to exploring the matter in such depth and with such thoroughness.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

One of the key tenets of Kant's work, is that there are two distinct types of propositions: an analytic proposition, which can be universally evaluated purely by considering the meaning of the words in the statement; and a synthetic proposition, which cannot be universally evaluated, because its truth-value depends on the state of the domain in question. Further, Kant distinguishes between an a priori proposition, which can be evaluated without any sensory experience; and an a posteriori proposition, which requires sensory experience in order to be evaluated.

So, analytic a priori statements are basically tautologies: e.g. "All triangles have three sides" – assuming the definition of a triangle (a 2D shape with three sides), and assuming the definition of a three-sided 2D shape (a triangle), this must always be true, and no knowledge of anything in the universe (except for those exact rote definitions) is required.

Conversely, synthetic a posteriori statements are basically unprovable real-world observations: e.g. "Neil Armstrong landed on the Moon in 1969" – maybe that "small step for man" TV footage is real, or maybe the conspiracy theorists are right and it was all a hoax; and anyway, even if your name was Buzz Aldrin, and you had seen Neil standing there right next to you on the Moon, how could you ever fully trust your own fallible eyes and your own fallible memory? It's impossible for there to be any logical proof for such a statement, it's only possible to evaluate it based on sensory experience.

Analytic a posteriori statements, according to Kant, are impossible to form.

Which leaves what Kant is most famous for, his discussion of synthetic a priori statements. An example of such a statement is: "A straight line between two points is the shortest". This is not a tautology – the terms "straight line between two points" and "shortest" do not define each other. Yet the statement can be universally evaluated as true, purely by logical consideration, and without any sensory experience. How is this so?

Kant asserts that there are certain concepts that are "hard-wired" into the human mind. In particular, the concepts of space, time, and causality. These concepts (or "forms of sensibility", to use Kant's terminology) form our "lens" of the universe. Hence, we are able to evaluate statements that have a universal truth, i.e. statements that don't depend on any sensory input, but that do nevertheless depend on these "intrinsic" concepts. In the case of the above example, it depends on the concept of space (two distinct points can exist in a three-dimensional space, and the shortest distance between them must be a straight line).

Another example is: "Every event has a cause". This is also universally true; at least, it is according to the intrinsic concepts of time (one event happens earlier in time, and another event happens later in time), and causality (events at one point in space and time, affect events at a different point in space and time). Maybe it would be possible for other reasoning entities (i.e. not humans) to evaluate these statements differently, assuming that such entities were imbued with different "intrinsic" concepts. But it is impossible for a reasoning human to evaluate those statements any other way.

The actual machinery of reasoning, as Kant explains, consists of twelve "categories" of understanding, each of which has a corresponding "judgement". These categories / judgements are essentially logic operations (although, strictly speaking, they predate the invention of modern predicate logic, and are based on Aristotle's syllogism), and they are as follows:

| Group | Categories / Judgements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity |

Unity Universal All trees have leaves |

Plurality Particular Some dogs are shaggy |

Totality Singular This ball is bouncy |

| Quality |

Reality Affirmative Chairs are comfy |

Negation Negative No spoons are shiny |

Limitation Infinite Oranges are not blue |

| Relation |

Inherence / Subsistence Categorical Happy people smile |

Causality / Dependence Hypothetical If it's February, then it's hot |

Community Disjunctive Potatoes are baked or fried |

| Modality |

Existence Assertoric Sharks enjoy eating humans |

Possibility Problematic Beer might be frothy |

Necessity Apodictic 6 times 7 equals 42 |

The cognitive mind is able to evaluate all of the above possible propositions, according to Kant, with the help of the intrinsic concepts (note that these intrinsic concepts are not considered to be "innate knowledge", as defined by the rationalist movement), and also with the help of the twelve categories of understanding.

Reason, therefore, is the ability to evaluate arbitrary propositions, using such cognitive faculties as logic and intuition, and based on understanding and sensibility, which are bridged by way of "forms of sensibility".

AI with intrinsic knowledge

If we consider existing AI with respect to the above definition of reason, it's clear that the capability is already developed maturely in some areas. In particular, existing AI – especially Knowledge Representation (KR) systems – has no problem whatsoever with formally evaluating predicate logic propositions. Existing AI – especially AI based on supervised learning methods – also excels at receiving and (crudely) processing large amounts of sensory input.

So, at one extreme end of the spectrum, there are pure ontological knowledge-base systems such as Cyc, where virtually all of the input into the system consists of hand-crafted factual propositions, and where almost none of the input is noisy real-world raw data. Such systems currently require a massive quantity of carefully curated facts to be on hand, in order to make inferences of fairly modest real-world usefulness.

Then, at the other extreme, there are pure supervised learning systems such as Google's NASNet, where virtually all of the input into the system consists of noisy real-world raw data, and where almost none of the input is human-formulated factual propositions. Such systems currently require a massive quantity of raw data to be on hand, in order to perform classification and regression tasks whose accuracy varies wildly depending on the target data set.

What's clearly missing, is something to bridge these two extremes. And, if transcendental idealism is to be our guide, then that something is "forms of sensibility". The key element of reason that humans have, and that machines currently lack, is a "lens" of the universe, with fundamental concepts of the nature of the universe – particularly of space, time, and causality – embodied in that lens.

Image source: Forbes

What fundamental facts about the universe would a machine require, then, in order to have "forms of sensibility" comparable to that of a human? Well, if we were to take this to the extreme, then a machine would need to be imbued with all the laws of mathematics and physics that exist in our universe. However, let's assume that going to this extreme is neither necessary nor possible, for various reasons, including: we humans are probably only imbued with a subset of those laws (the ones that apply most directly to our everyday existence); it's probably impossible to discover the full set of those laws; and, we will assume that, if a reasoning entity is imbued only with an appropriate subset of those laws, then it's possible to deduce the remainder of the laws (and it's therefore also possible to deduce all other facts relating to observable phenomena in the universe).

I would, therefore, like to humbly suggest, in plain English, what some of these fundamental facts, suitable for comprising the "forms of sensibility" of a reasoning machine, might be:

- There are four dimensions: three space dimensions, and one time dimension

- An object exists if it occupies one or more points in space and time

- An object exists at zero or one points in space, given a particular point in time

- An object exists at zero or more points in time, given a particular point in space

- An event occurs at one point in space and time

- An event is caused by one or more different events at a previous point in time

- Movement is an event that involves an object changing its position in space and time

- An object can observe its relative position in, and its movement through, space and time, using the space concepts of left, right, ahead, behind, up, and down, and using the time concepts of forward and backward

- An object can move in any direction in space, but can only move forward in time

I'm not suggesting that the above list is really a sufficient number of intrinsic concepts for a reasoning machine, nor that all of the above facts are the correct choice nor correctly worded for such a list. But this list is a good start, in my opinion. If an "intelligent" machine were to be appropriately imbued with those facts, then that should be a sufficient foundation for it to evaluate matters of space, time, and causality.

There are numerous other intrinsic aspects of human understanding that it would also, arguably, be essential for a reasoning machine to possess. Foremost of these is the concept of self: does AI need a hard-wired idea of "I"? Other such concepts include matter / substance, inertia, life / death, will, freedom, purpose, and desire. However, it's a matter of debate, rather than a given, whether each of these concepts is fundamental to the foundation of human-like reasoning, or whether each of them is learned and acquired as part of intellectual experience.

Reasoning AI

A machine as discussed so far is a good start, but it's still not enough to actually yield what would be considered human-like intelligence. Cyc, for example, is an existing real-world system that basically already has all these characteristics – it can evaluate logical propositions of arbitrary complexity, based on a corpus (a much larger one than my humble list above) of intrinsic facts, and based on some sensory input – yet no real intelligence has emerged from it.

One of the most important missing ingredients, is the ability to hypothesise. That is, based on the raw sensory input of real-world phenomena, the ability to observe a pattern, and to formulate a completely new, original proposition expressing that pattern as a rule. On top of that, it includes the ability to test such a proposition against new data, and, when the rule breaks, to modify the proposition such that the rule can accommodate that new data. That, in short, is what is known as deductive reasoning.

A child formulates rules in this way. For example, a child observes that when she drops a drinking glass, the glass shatters the moment that it hits the floor. She drops a glass in this way several times, just for fun (plenty of fun for the parents too, naturally), and observes the same result each time. At some point, she formulates a hypothesis along the lines of "drinking glasses break when dropped on the floor". She wasn't born knowing this, nor did anyone teach it to her; she simply "worked it out" based on sensory experience.

Some time later, she drops a glass onto the floor in a different room of the house, still from shoulder-height, but it does not break. So she modifies the hypothesis to be "drinking glasses break when dropped on the kitchen floor" (but not the living room floor). But then she drops a glass in the bathroom, and in that case it does break. So she modifies the hypothesis again to be "drinking glasses break when dropped on the kitchen or the bathroom floor".

But she's not happy with this latest hypothesis, because it's starting to get complex, and the human mind strives for simple rules. So she stops to think about what makes the kitchen and bathroom floors different from the living room floor, and realises that the former are hard (tiled), whereas the latter is soft (carpet). So she refines the hypothesis to be "drinking glasses break when dropped on a hard floor". And thus, based on trial-and-error, and based on additional sensory experience, the facts that comprise her understanding of the world have evolved.

Image source: CoreSight

Some would argue that current state-of-the-art AI is already able to formulate rules, by way of feature learning (e.g. in image recognition). However, a "feature" in a neural network is just a number, either one directly taken from the raw data, or one derived based on some sort of graph function. So when a neural network determines the "features" that correspond to a duck, those features are just numbers that represent the average outline of a duck, the average colour of a duck, and so on. A neural network doesn't formulate any actual facts about a duck (e.g. "ducks are yellow"), which can subsequently be tested and refined (e.g. "bath toy ducks are yellow"). It just knows that if the image it's processing has a yellowish oval object occupying the main area, there's a 63% probability that it's a duck.

Another faculty that the human mind possesses, and that AI currently lacks, is intuition. That is, the ability to reach a conclusion based directly on sensory input, without resorting to logic as such. The exact definition of intuition, and how it differs from instinct, is not clear (in particular, both are sometimes defined as a "gut feeling"). It's also unclear whether or not some form of intuition is an essential ingredient of human-like intelligence.

It's possible that intuition is nothing more than a set of rules, that get applied either before proper logical reasoning has a chance to kick in (i.e. "first resort"), or after proper logical reasoning has been exhausted (i.e. "last resort"). For example, perhaps after a long yet inconclusive analysis of competing facts, regarding whether your Uncle Jim is telling the truth or not when he claims to have been to Mars (e.g. "Nobody has ever been to Mars", "Uncle Jim showed me his medal from NASA", "Mum says Uncle Jim is a flaming crackpot", "Uncle Jim showed me a really red rock"), your intuition settles the matter with the rule: "You should trust your own family". But, on the other hand, it's also possible that intuition is a more elementary mechanism, and that it can't be expressed in the form of logical rules at all: instead, it could simply be a direct mapping of "situations" to responses.

Is reason enough?

In order to test whether a hypothetical machine, as discussed so far, is "good enough" to be considered intelligent, I'd like to turn to one of the domains that current-generation AI is already pursuing: criminal justice assessment. One particular area of this domain, in which the use of AI has grown significantly, is determining whether an incarcerated person should be approved for parole or not. Unsurprisingly, AI's having input into such a decision has so far, in real life, not been considered altogether successful.

The current AI process for this is based almost entirely on statistical analysis. That is, the main input consists of simple numeric parameters, such as: number of incidents reported during imprisonment; level of severity of the crime originally committed; and level of recurrence of criminal activity. The input also includes numerous profiling parameters regarding the inmate, such as: racial / ethnic group; gender; and age. The algorithm, regardless of any bells and whistles it may claim, is invariably simply answering the question: for other cases with similar input parameters, were they deemed eligible for parole? And if so, did their conduct after release demonstrate that they were "reformed"? And based on that, is this person eligible for parole?

Current-generation AI, in other words, is incapable of considering a single such case based on its own merits, nor of making any meaningful decision regarding that case. All it can do, is compare the current case to its training data set of other cases, and determine how similar the current case is to those others.

A human deciding parole eligibility, on the other hand, does consider the case in question based on its own merits. Sure, a human also considers the numeric parameters and the profiling parameters that a machine can so easily evaluate. But a human also considers each individual event in the inmate's history as a stand-alone fact, and each such fact can affect the final decision differently. For example, perhaps the inmate seriously assaulted other inmates twice while imprisoned. But perhaps he also read 150 novels, and finished a university degree by correspondence. These are not just statistics, they're facts that must be considered, and each fact must refine the hypothesis whose final form is either "this person is eligible for parole", or "this person is not eligible for parole".

A human is also influenced by morals and ethics, when considering the character of another human being. So, although the question being asked is officially: "is this person eligible for parole?", the question being considered in the judge's head may very well actually be: "is this person good or bad?". Should a machine have a concept of ethics, and/or of good vs bad, and should it apply such ethics when considering the character of an individual human? Most academics seem to think so.

According to Kant, ethics is based on a foundation of reason. But that doesn't mean that a reasoning machine is automatically an ethical machine, either. Does AI need to understand ethics, in order to possess what we would consider human-like intelligence?

Although decisions such as parole eligibility are supposed to be objective and rational, a human is also influenced by emotions, when considering the character of another human being. Maybe, despite the evidence suggesting that the inmate is not reformed, the judge is stirred by a feeling of compassion and pity, and this feeling results in parole being granted. Or maybe, despite the evidence being overwhelmingly positive, the judge feels fear and loathing towards the inmate, mainly because of his tough physical appearance, and this feeling results in parole being denied.

Should human-like AI possess the ability to be "stirred" by such emotions? And would it actually be desirable for AI to be affected by such emotions, when evaluating the character of an individual human? Some such emotions might be considered positive, while others might be considered negative (particularly from an ethical point of view).

I think the ultimate test in this domain – perhaps the "Turing test for criminal justice assessment" – would be if AI were able to understand, and to properly evaluate, this great parole speech, which is one of my personal favourite movie quotes:

There's not a day goes by I don't feel regret. Not because I'm in here, or because you think I should. I look back on the way I was then: a young, stupid kid who committed that terrible crime. I want to talk to him. I want to try and talk some sense to him, tell him the way things are. But I can't. That kid's long gone and this old man is all that's left. I got to live with that. Rehabilitated? It's just a bulls**t word. So you can go and stamp your form, Sonny, and stop wasting my time. Because to tell you the truth, I don't give a s**t.

"Red" (Morgan Freeman)

Image source: YouTube

In the movie, Red's parole was granted. Could we ever build an AI that could also grant parole in that case, and for the same reasons? On top of needing the ability to reason with real facts, and to be affected by ethics and by emotion, properly evaluating such a speech requires the ability to understand humour – black humour, no less – along with apathy and cynicism. No small task.

Conclusion

Sorry if you were expecting me to work wonders in this article, and to actually teach the world how to build artificial intelligence that reasons. I don't have the magic answer to that million dollar question. However, I hope I have achieved my aim here, which was to describe what's needed in order for it to even be possible for such AI to come to fruition.

It should be clear, based on what I've discussed here, that most current-generation AI is based on a completely inadequate foundation for even remotely human-like intelligence. Chucking big data at a statistic-crunching algorithm on a fat cluster might be yielding cool and even useful results, but it will never yield intelligent results. As centuries of philosophical debate can teach us – if only we'd stop and listen – human intelligence rests on specific building blocks. These include, at the very least, an intrinsic understanding of time, space, and causality; and the ability to hypothesise based on experience. If we are to ever build a truly intelligent artificial agent, then we're going to have to figure out how to imbue it with these things.

Further reading

- Immanuel Kant: Aesthetics

- The Mismatch Between Human and Machine Knowledge (1994)

- Gödel, Consciousness and the Weak vs. Strong AI Debate

- Transforming Kantian Aesthetic Principles into Qualitative Hermeneutics for Contemplative AGI Agents (2018)

- Recognizing context is still hard in Machine Learning — here’s how to tackle it

- Towards Deep Symbolic Reinforcement Learning (2016)

- Generality in Artificial Intelligence (1987)

- The Symbol Grounding Problem (1990)

- Aristotle’s Ten Categories

- Computational Beauty: Aesthetic Judgment at the Intersection of Art and Science (2014)

- Philosophy of artificial intelligence

- A proposal for ethically traceable artificial intelligence (2017)

- Commonsense knowledge (artificial intelligence)

- Kant's Critique of Pure Reason

- Schopenhauer on Space, Time, Causality and Matter: A Physical Re-examination (2018)

- A Brief Introduction to Temporality and Causality (2010)

- Sequences of Mechanisms for Causal Reasoning in Artificial Intelligence (2013)

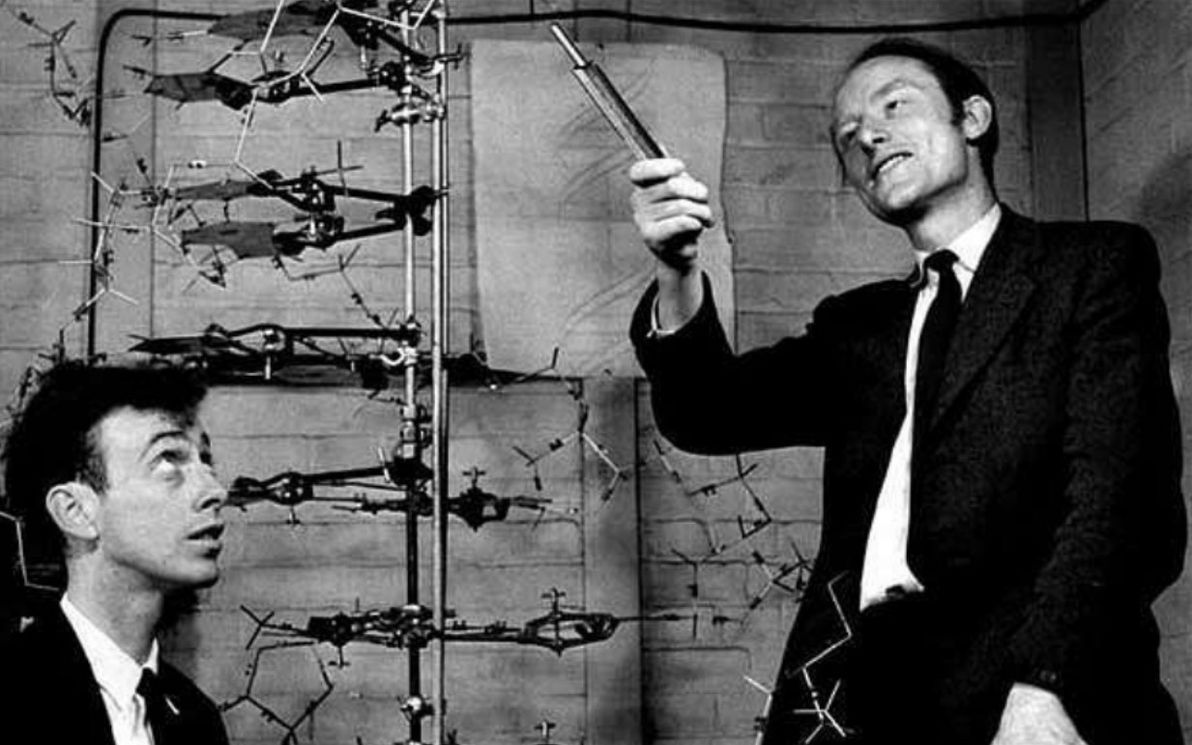

Most intriguing and most tantalising of all, is the fact that we humans still have virtually no idea how to interpret DNA in any meaningful way. It's only since 1953 that we've understood what DNA even is; and it's only since 2001 that we've been able to extract and to gaze upon instances of the complete human genome.

Image source: A complete PPT on DNA (Slideshare).

As others have pointed out, the reason why we haven't had much luck in reading DNA, is because (in computer science parlance) it's not high-level source code, it's machine code (or, to be more precise, it's bytecode). So, DNA, which is sequences of base-4 digits, grouped into (most commonly) 3-digit "words" (known as "codons"), is no more easily decipherable than binary, which is sequences of base-2 digits, grouped into (for example) 8-digit "words" (known as "bytes"). And as anyone who has ever read or written binary (in binary, octal, or hex form, however you want to skin that cat) can attest, it's hard!

In this musing, I'm going to compare genetic code and computer code. I am in no way qualified to write about this topic (particularly about the biology side), but it's fun, and I'm reckless, and this is my blog so for better or for worse nobody can stop me.

Authorship and motive

The first key difference that I'd like to point out between the two, is regarding who wrote each one, and why. For computer code, this is quite straightforward: a given computer program was written by one of your contemporary human peers (hopefully one who is still alive, as you can then ask him or her about anything that's hard to grok in the code), for some specific and obvious purpose – for example, to add two numbers together, or to move a chomping yellow pac-man around inside a maze, or to add somersaulting cats to an image.

For DNA, we don't know who, if anyone, wrote the first ever snippet of code – maybe it was G-d, maybe it was aliens from the Delta Quadrant, or maybe it was the random result of various chemicals bashing into each other within the primordial soup. And as for who wrote (and who continues to this day to write) all DNA after that, that too may well be The Almighty or The Borg, but the current theory of choice is that a given snippet of DNA basically keeps on re-writing itself, and that this auto-re-writing happens (as far as we can tell) in a pseudo-random fashion.

Image source: Art UK.

Nor do we know why DNA came about in the first place. From a philosophical / logical point of view, not having an answer to the "who" question, kind of makes it impossible to address the "why", by defintion. If it came into existence randomly, then it would logically follow that it wasn't created for any specific purpose, either. And as for why DNA re-writes itself in the way that it does: it would seem that DNA's, and therefore life's, main purpose, as far as the DNA itself is concerned, is simply to continue existing / surviving, as evidenced by the fact that DNA's self-modification results, on average, over the long-term, in it becoming ever more optimally adapted to its surrounding environment.

Management processes

For building and maintaining computer software, regardless of "methodology" (e.g. waterfall, scrum, extreme programming), the vast majority of the time there are a number of common non-dev processes in place. Apart from every geek's favourite bit, a.k.a. "coding", there is (to name a few): requirements gathering; spec writing; code review; testing / QA; version control; release management; staged deployment; and documentation. The whole point of these processes, is to ensure: that a given snippet of code achieves a clear business or technical outcome; that it works as intended (both in isolation, and when integrated into the larger system); that the change it introduces is clearly tracked and is well-communicated; and that the codebase stays maintainable.

For DNA, there is little or no parallel to most of the above processes. As far as we know, when DNA code is modified, there are no requirements defined, there is no spec, there is no review of the change, there is no staging environment, and there is no documentation. DNA seems to follow my former boss's preferred methodology: JFDI. New code is written, nobody knows what it's for, nobody knows how to use it. Oh well. Straight into production it goes.

However, there is one process that DNA demonstrates in abundance: QA. Through a variety of mechanisms, the most important of which is repair enzymes, a given piece of DNA code is constantly checked for integrity errors, and these errors are generally repaired. Mutations (i.e. code changes) can occur during replication due to imperfect copying, or at any other time due to environmental factors. Depending on the genome (i.e. the species) in question, and depending on the gene in question, the level of enforcement of DNA integrity can vary, from "very relaxed" to "very strict". For example, bacteria experience far more mutation between generations than humans do. This is because some genomes consider themselves to still be in "beta", and are quite open to potentially dangerous experimentation, while other genomes consider themselves "mature", and so prefer less change and greater stability. Thus a balance is achieved between preservation of genes, and evolution.

The coding process

For computer software, the actual process of coding is relatively structured and rational. The programmer refers to the spec – which could be anything from a one-sentence verbal instruction bandied over the water-cooler, to a 50-page PDF (preferably it's something in between those two extremes) – before putting hands to keyboard, and also regularly while coding.

The programmer visualises the rough overall code change involved (or the rough overall components of a new codebase), and starts writing. He or she will generally switch between top-down (focusing on the framework and on "glue code") and bottom-up (focusing on individual functions) several times. The code will generally be refined, in response to feedback during code review, to fixing defects in the change, and to the programmer's constant critiquing of his or her own work. Finally, the code will be "done" – although inevitably it will need to be modified in future, in response to new requirements, at which point it's time to rinse and repeat all of the above.

For DNA, on the other hand, the process of coding appears (unless we're missing something?) to be akin to letting a dog randomly roll around on the keyboard while the editor window is open, then cleaning up the worst of the damage, then seeing if anything interesting was produced. Not the most scientific of methods, you might say? But hey, that's science! And it would seem that, amazingly, if you do that on a massively distributed enough scale, over a long enough period of time, you get intelligent life.

Image source: DogsToday.

When you think about it, that approach isn't really dissimilar to the current state-of-the-art in machine learning. Getting anything approaching significant or accurate results with machine learning models, has only been possible quite recently, thanks to the availability of massive data sets, and of massive hardware platforms – and even when you let a ML algorithm loose in that environment for a decent period of time, it produces results that contain a lot of noise. So maybe we are indeed onto something with our current approach to ML, although I don't think we're quite onto the generation of truly intelligent software just yet.

Grokking it

Most computer code that has been written by humans for the past 40 years or so, has been high-level source code (i.e. "C and up"). It's written primarily to express business logic, rather than to tell the Von Neumann machine (a.k.a. the computer hardware) exactly what to do. It's up to the compiler / interpreter, to translate that "call function abc" / "divide variable pqr by 50" / "write the string I feel like a Tooheys to file xyz" code, into "load value of register 123" / "put that value in register 456" / "send value to bus 789" code, which in turn actually gets represented in memory as 0s and 1s.

This is great for us humans, because – assuming we can get our hands on the high-level source code – we can quite easily grok the purpose of a given piece of code, without having to examine the gory details of what the computer physically does, step-by-tiny-tedious-step, in order to achieve that noble purpose.

DNA, as I said earlier, is not high-level source code, it's machine code / bytecode (more likely the latter, in which case the actual machine code of living organisms is the proteins, and other things, that DNA / RNA gets "compiled" to). And it now seems pretty clear that there is no higher source code – DNA, which consists of long sequences of Gs, As, Cs, and Ts, is the actual source. The code did not start in a form where a given gene is expressed logically / procedurally – a form from which it could be translated down to base pairs. The start and the end state of the code is as base pairs.

Image source: The University Network.

It also seems that DNA is harder to understand than machine / assembly code for a computer, because an organic cell is a much more complex piece of hardware than a Von Neumann-based computer (which itself is a specific type of Turing machine). That's why humans were perfectly capable of programming computers using only machine / assembly code to begin with, and why some specialised programmers continue primarily coding at that level to this day. For a computer, the machine itself only consists of a few simple components, and the instruction set is relatively small and unambiguous. For an organic cell, the physical machinery is far more complex (and whether a DNA-containing cell is a Turing machine is itself currently an open research question), and the instruction set is riddled with ambiguous, context-specific meanings.

Since all we have is the DNA bytecode, all current efforts to "decode DNA" focus on comparing long strings of raw base pairs with each other, across different genes / chromosomes / genomes. This is akin to trying to understand what software does by lining up long strings of compiled hex digits for different binaries side-by-side, and spotting sequences that are kind-of similar. So, no offense intended, but the current state-of-the-art in "DNA decoding" strikes me as incredibly primitive, cumbersome, and futile. It's a miracle that we've made any progress at all with this approach, and it's only thanks to some highly intelligent people employing their best mathematical pattern analysis techniques, that we have indeed gotten anywhere.

Where to from here?

Personally, I feel that we're only really going to "crack" the DNA puzzle, if we're able to reverse-engineer raw DNA sequences into some sort of higher-level code. And, considering that reverse-engineering raw binary into a higher-level programming language (such as C) is a very difficult endeavour, and that doing the same for DNA is bound to be even harder, I think we have our work cut out for us.

My interest in the DNA puzzle was first piqued, when I heard a talk at PyCon AU 2016: Big data biology for pythonistas: getting in on the genomics revolution, presented by Darya Vanichkina. In this presentation, DNA was presented as a riddle that more programmers can and should try to help solve. Since then, I've thought about the riddle now and then, and I have occasionally read some of the plethora of available online material about DNA and genome sequencing.

DNA is an amazing thing: for approximately 4 billion years, it has been spreading itself across our planet, modifying itself in bizarre and colourful ways, and ultimately evolving (according to the laws of natural selection) to become the codebase that defines the behaviour of primitive lifeforms such as humans (and even intelligent lifeforms such as dolphins!).

Image source: Days of the Year.

So, let's be realistic here: it took DNA that long to reach its current form; we'll be doing well if we can start to understand it properly within the next 1,000 years, if we can manage it at all before the humble blip on Earth's timeline that is human civilisation fades altogether.

]]>

Image source: Day of the Robot.

Most discussion of late seems to treat this encroaching joblessness entirely as an economic issue. Families without incomes, spiralling wealth inequality, broken taxation mechanisms. And, consequently, the solutions being proposed are mainly economic ones. For example, a Universal Basic Income to help everyone make ends meet. However, in my opinion, those economic issues are actually relatively easy to address, and as a matter of sheer necessity we will sort them out sooner or later, via a UBI or via whatever else fits the bill.

The more pertinent issue is actually a social and a psychological one. Namely: how will people keep themselves occupied in such a world? How will people nourish their ambitions, feel that they have a purpose in life, and feel that they make a valuable contribution to society? How will we prevent the malaise of despair, depression, and crime from engulfing those who lack gainful enterprise? To borrow the colourful analogy that others have penned: assuming that there's food on the table either way, how do we head towards a Star Trek rather than a Mad Max future?

Keep busy

The truth is, since the Industrial Revolution, an ever-expanding number of people haven't really needed to work anyway. What I mean by that is: if you think about what jobs are actually about providing society with the essentials such as food, water, shelter, and clothing, you'll quickly realise that fewer people than ever are employed in such jobs. My own occupation, web developer, is certainly not essential to the ongoing survival of society as a whole. Plenty of other occupations, particularly in the services industry, are similarly remote from humanity's basic needs.

So why do these jobs exist? First and foremost, demand. We live in a world of free markets and capitalism. So, if enough people decide that they want web apps, and those people have the money to make it happen, then that's all that's required for "web developer" to become and to remain a viable occupation. Second, opportunity. It needs to be possible to do that thing known as "developing web apps" in the first place. In many cases, the opportunity exists because of new technology; in my case, the Internet. And third, ambition. People need to have a passion for what they do. This means that, ideally, people get to choose an occupation of their own free will, rather than being forced into a certain occupation by their family or by the government. If a person has a natural talent for his or her job, and if a person has a desire to do the job well, then that benefits the profession as a whole, and, in turn, all of society.

Those are the practical mechanisms through which people end up spending much of their waking life at work. However, there's another dimension to all this, too. It is very much in the interest of everyone that makes up "the status quo" – i.e. politicians, the police, the military, heads of big business, and to some extent all other "well to-do citizens" – that most of society is caught up in the cycle of work. That's because keeping people busy at work is the most effective way of maintaining basic law and order, and of enforcing control over the masses. We have seen throughout history that large-scale unemployment leads to crime, to delinquency and, ultimately, to anarchy. Traditionally, unemployment directly results in poverty, which in turn directly results in hunger. But even if the unemployed get their daily bread – even if the crisis doesn't reach let them eat cake proportions – they are still at risk of falling to the underbelly of society, if for no other reason, simply due to boredom.

So, assuming that a significantly higher number of working-age men and women will have significantly fewer job prospects in the immediate future, what are we to do with them? How will they keep themselves occupied?

The Games

I propose that, as an alternative to traditional employment, these people engage in large-scale, long-term, government-sponsored, semi-recreational activities. These must be activities that: (a) provide some financial reward to participants; (b) promote physical health and social well-being; and (c) make a tangible positive contribution to society. As a massive tongue-in-cheek, I call this proposal "The Jobless Games".

My prime candidate for such an activity would be a long-distance walk. The journey could take weeks, months, even years. Participants could number in the hundreds, in the thousands, even in the millions. As part of the walk, participants could do something useful, too; for example, transport non-urgent goods or mail, thus delivering things that are actually needed by others, and thus competing with traditional freight services. Walking has obvious physical benefits, and it's one of the most social things you can do while moving and being active. Such a journey could also be done by bicycle, on horseback, or in a variety of other modes.

Image source: The New Paper.

Other recreational programs could cover the more adventurous activities, such as climbing, rafting, and sailing. However, these would be less suitable, because: they're far less inclusive of people of all ages and abilities; they require a specific climate and geography; they're expensive in terms of equipment and expertise; they're harder to tie in with some tangible positive end result; they're impractical in very large groups; and they damage the environment if conducted on too large a scale.

What I'm proposing is not competitive sport. These would not be races. I don't see what having winners and losers in such events would achieve. What I am proposing is that people be paid to participate in these events, out of the pocket of whoever has the money, i.e. governments and big business. The conditions would be simple: keep up with the group, and behave yourself, and you keep getting paid.

I see such activities co-existing alongside whatever traditional employment is still available in future; and despite all the doom and gloom predictions, the truth is that there always has been real work out there, and there always will be. My proposal is that, same as always, traditional employment pays best, and thus traditional employment will continue to be the most attractive option for how to spend one's days. Following that, "The Games" pay enough to get by on, but probably not enough to enjoy all life's luxuries. And, lastly, as is already the case in most first-world countries today, for the unemployed there should exist a social security payment, and it should pay enough to cover life's essentials, but no more than that. We already pay people sit down money; how about a somewhat more generous payment of stand up money?

Along with these recreational activities that I've described, I think it would also be a good idea to pay people for a lot of the work that is currently done by volunteers without financial reward. In a future with less jobs, anyone who decides to peel potatoes in a soup kitchen, or to host bingo games in a nursing home, or to take disabled people out for a picnic, should be able to support him- or herself and to live in a dignified manner. However, as with traditional employment, there are also only so many "volunteer" positions that need filling, and even with that sector significantly expanded, there would still be many people left twiddling their thumbs. Which is why I think we need some other solution, that will easily and effectively get large numbers of people on their feet. And what better way to get them on their feet, than to say: take a walk!

Large-scale, long-distance walks could also solve some other problems that we face at present. For example, getting a whole lot of people out of our biggest and most crowded cities, and "going on tour" to some of our smallest and most neglected towns, would provide a welcome economic boost to rural areas, considering all the support services that such activities would require; while at the same time, it would ease the crowding in the cities, and it might even alleviate the problem of housing affordability, which is acute in Australia and elsewhere. Long-distance walks in many parts of the world – particularly in Europe – could also provide great opportunities for an interchange of language and culture.

In summary

There you have it, my humble suggestion to help fill the void in peoples' lives in the future. There are plenty of other things that we could start paying people to do, that are more intellectual and that make a more tangible contribution to society: e.g. create art, be spiritual, and perform in music and drama shows. However, these things are too controversial for the government to support on such a large scale, and their benefit is a matter of opinion. I really think that, if something like this is to have a chance of succeeding, it needs to be dead simple and completely uncontroversial. And what could be simpler than walking?

Whatever solutions we come up with, I really think that we need to start examining the issue of 21st-century job redundancy from this social angle. The economic angle is a valid one too, but it has already been analysed quite thoroughly, and it will sort itself out with a bit of ingenuity. What we need to start asking now is: for those young, fit, ambitious people of the future that lack job prospects, what activity can they do that is simple, social, healthy, inclusive, low-impact, low-cost, and universal? I'd love to hear any further suggestions you may have.

]]>Societal vices have always been bountiful. Back in the ol' days, it was just the usual suspects. War. Violence. Greed. Corruption. Injustice. Propaganda. Lewdness. Alcoholism. To name a few. In today's world, still more scourges have joined in the mix. Consumerism. Drug abuse. Environmental damage. Monolithic bureaucracy. And plenty more.

There always have been some folks who elect to isolate themselves from the masses, to renounce their mainstream-ness, to protect themselves from all that nastiness. And there always will be. Nothing wrong with doing so.

However, there's a difference between protecting oneself from "the evils of society", and blinding oneself to their very existence. Sometimes this difference is a fine line. Particularly in the case of families, where parents choose to shield from the Big Bad World not only themselves, but also their children. Protection is noble and commendable. Blindfolding, in my opinion, is cowardly and futile.

Image source: greenskullz1031 on Photobucket.

Seclusion

There are plenty of examples from bygone times, of historical abstainers from mainstream society. Monks and nuns, who have for millenia sought serenity, spirituality, abstinence, and isolation from the material. Hermits of many varieties: witches, grumpy old men / women, and solitary island-dwellers.

Religion has long been an important motive for seclusion. Many have settled on a reclusive existence as their solution to avoiding widespread evils and being closer to G-d. Other than adult individuals who choose a monastic life, there are also whole communities, composed of families with children, who live in seclusion from the wider world. The Amish in rural USA are probably the most famous example, and also one of the longest-running such communities. Many ultra-orthodox Jewish communities, particularly within present-day Israel, could also be considered as secluded.

Image source: Wikipedia: Amish.

More recently, the "commune living" hippie phenomenon has seen tremendous growth worldwide. The hippie ideology is, of course, generally an anti-religious one, with its acceptance of open relationships, drug use, lack of hierarchy, and often a lack of any formal G-d. However, the secluded lifestyle of hippie communes is actually quite similar to that of secluded religious groups. It's usually characterised by living amidst, and in tune with, nature; rejecting modern technology; and maintaining a physical distance from regular urban areas. The left-leaning members of these communities tend to strongly shun consumerism, and to promote serenity and spirituality, much like their G-d fearing comrades.

In a bubble

Like the members of these communities, I too am repulsed by many of the "evils" within the society in which we live. Indeed, the idea of joining such a community is attractive to me. It would be a pleasure and a relief to shut myself out from the blight that threatens me, and from everyone that's "infected" by it. Life would be simpler, more peaceful, more wholesome.

I empathise with those who have chosen this path in life. Just as it's tempting to succumb to all the world's vices, so too is it tempting to flee from them. However, such people are also living in a bubble. An artificial world, from which the real world has been banished.

What bothers me is not so much the independent adult people who have elected for such an existence. Despite all the faults of the modern world, most of us do at least enjoy far-reaching liberty. So, it's a free land, and adults are free to live as they will, and to blind themselves to what they will.

What does bother me, is that children are born and raised in such an existence. The adult knows what it is that he or she is shut off from, and has experienced it before, and has decided to discontinue experiencing it. The child, on the other hand, has never been exposed to reality, he or she knows only the confines of the bubble. The child is blind, but to what, it knows not.

Image source: CultureLab: Breaking out of the internet filter bubble.

This is a cowardly act on the part of the parents. It's cowardly because a child only develops the ability to combat and to reject the world's vices, such as consumerism or substance abuse, by being exposed to them, by possibly experimenting with them, and by making his or her own decisions. Parents that are serious about protecting their children do expose them to the Big Bad World, they do take risks; but they also do the hard yards in preparing their children for it: they ensure that their children are raised with education, discipline, and love.

Blindfolding children to the reality of wider society is also futile — because, sooner or later, whether still as children or later as adults, the Big Bad World exposes itself to all, whether you like it or not. No Amish countryside, no hippie commune, no far-flung island, is so far or so disconnected from civilisation that its inhabitants can be prevented from ever having contact with it. And when the day of exposure comes, those that have lived in their little bubble find themselves totally unprepared for the very "evils" that they've supposedly been protected from for all their lives.

Keep it balanced

In my opinion, the best way to protect children from the world's vices, is to expose them in moderation to the world's nasty underbelly, while maintaining a stable family unit, setting a strong example of rejecting the bad, and ensuring a solid education. That is, to do what the majority of the world's parents do. That's right: it's a formula that works reasonably well for billions of people, and that has been developed over thousands of years, so there must be some wisdom to it.

Obviously, children need to be protected from dangers that could completely overwhelm them. Bringing up a child in a favela environment is not ideal, and sometimes has horrific consequences, just watch City of G-d if you don't believe me. But then again, blindfolding is the opposite extreme; and one extreme can be as bad as the other. Getting the balance somewhere in between is the key.

]]>Oh, you think that's funny? I'm being serious.

Alright, then. I'm going to try and solve them. Money is a concept, a product and a system that's been undergoing constant refinement since the dawn of civilisation; and, as the world's current financial woes are testament to, it's clear that we still haven't gotten it quite right. That's because getting financial systems right is hard. If it were easy, we'd have done it already.

I'm going to start with some background, discussing the basics such as: what is money, and where does it come from? What is credit? What's the history of money, and of credit? How do central banks operate? How do modern currencies attain value? And then I'm going to move on to the fun stuff: what can we do to improve the system? What's the next step in the ongoing evolution of money and finance?

Disclaimer: I am not an economist or a banker; I have no formal education in economics or finance; and I have no work experience in these fields. I'm just a regular bloke, who's been thinking about these big issues, and reading up on a lot of material, and who would like to share his understandings and his conclusions with the world.

Ancient history

Money has been around for a while. When I talk about money, I'm talking cash. The stuff that leaves a smell on your fingers. The stuff that jingles in your pockets. Cold hard cash.

The earliest known example of money dates back to the 7th century BC, when the Lydians minted coins using a natural gold-based alloy called electrum. They were a crude affair – with each coin being of a slightly different shape – but they evolved to become reasonably consistent in their weight in precious metal; and many of them also bore official seals or insignias.

Source: Ancient coins.

From Lydia, the phenomenom of minted precious-metal coinage spread: first to her immediate neighbours – the Greek and Persian empires – and then to the rest of the civilised world. By the time the Romans rose to significance, around the 3rd century BC, coinage had become the norm as a medium of exchange; and the Romans established this further with their standard-issue coins, most notably the Denarius, which were easily verifiable and reliable in their precious metal content.

Source: London Evening Standard. Quote: Life of Brian haggling scene.

Money, therefore, is nothing new. This should come as no surprise to you.

What may surprise you, however, is that credit existed before the arrival of money. How can that be? I hear you say. Isn't credit – the business of lending, and of recording and repaying a debt – a newer and more advanced concept than money? No! Quite the reverse. In fact, credit is the most fundamental concept of all in the realm of commerce; and historical evidence shows that it was actually established and refined, well before cold hard cash hit the scene. I'll elaborate further when I get on to definitions (next section). For now, just bear with me.

One of the earliest known historical examples of credit – in the form of what essentially amount to "IOU" documents – is from Ancient Babylonia:

… in ancient Babylonia … common commercial documents … are what are called "contract tablets" or "shuhati tablets" … These tablets, the oldest of which were in use from 2000 to 3000 years B. C. are of baked or sun-dried clay … The greater number are simple records of transactions in terms of "she," which is understood by archaeologists to be grain of some sort.

…

From the frequency with which these tablets have been met with, from the durability of the material of which they are made, from the care with which they were preserved in temples which are known to have served as banks, and more especially from the nature of the inscriptions, it may be judged that they correspond to the medieval tally and to the modern bill of exchange; that is to say, that they are simple acknowledgments of indebtedness given to the seller by the buyer in payment of a purchase, and that they were the common instrument of commerce.

But perhaps a still more convincing proof of their nature is to be found in the fact that some of the tablets are entirely enclosed in tight-fitting clay envelopes or "cases," as they are called, which have to be broken off before the tablet itself can be inspected … The particular significance of these "case tablets" lies in the fact that they were obviously not intended as mere records to remain in the possession of the debtor, but that they were signed and sealed documents, and were issued to the creditor, and no doubt passed from hand to hand like tallies and bills of exchange. When the debt was paid, we are told that it was customary to break the tablet.

We know, of course, hardly anything about the commerce of those far-off days, but what we do know is, that great commerce was carried on and that the transfer of credit from hand to hand and from place to place was as well known to the Babylonians as it is to us. We have the accounts of great merchant or banking firms taking part in state finance and state tax collection, just as the great Genoese and Florentine bankers did in the middle ages, and as our banks do to-day.

Source: What is Money?

Original source: The Banking Law Journal, May 1913, By A. Mitchell Innes.

As the source above mentions (and as it describes in further detail elsewhere), another historical example of credit – as opposed to money – is from medieval Europe, where the split tally stick was commonplace. In particular, in medieval England, the tally stick became a key financial instrument used for taxation and for managing the Crown accounts:

A tally stick is "a long wooden stick used as a receipt." When money was paid in, a stick was inscribed and marked with combinations of notches representing the sum of money paid, the size of the cut corresponding to the size of the sum. The stick was then split in two, the larger piece (the stock) going to the payer, and the smaller piece being kept by the payee. When the books were audited the official would have been able to produce the stick with exactly matched the tip, and the stick was then surrendered to the Exchequer.

Tallies provide the earliest form of bookkeeping. They were used in England by the Royal Exchequer from about the twelfth century onward. Since the notches for the sums were cut right through both pieces and since no stick splits in an even manner, the method was virtually foolproof against forgery. They were used by the sheriff to collect taxes and to remit them to the king. They were also used by private individuals and institutions, to register debts, record fines, collect rents, enter payments for services rendered, and so forth. By the thirteenth century, the financial market for tallies was sufficiently sophisticated that they could be bought, sold, or discounted.

Source: Tally sticks.

Source: The National Archives.

It should be noted that unlike the contract tablets of Babylonia (and the similar relics of other civilisations of that era), the medieval tally stick existed alongside an established metal-coin-based money system. The ancient tablets recorded payments made, or debts owed, in raw goods (e.g. "on this Tuesday, Bishbosh the Great received eight goats from Hammalduck", or "as of this Thursday, Kimtar owes five kwetzelgrams of silver and nine bushels of wheat to Washtawoo"). These societies may have, in reality, recorded most transactions in terms of precious metals (indeed, it's believed that the silver shekel emerged as the standard unit in ancient Mesopotamia); but these units had non-standard shapes and were unsigned, whereas classical coinage was uniform in shape, and possessed insignias.

In medieval England, the common currency was sterling silver, which consisted primarily of silver penny coins (but there were also silver shilling coins, and gold pound coins). The medieval tally sticks recorded payments made, or debts owed, in monetary value (e.g. "on this Monday, Lord Snottyham received one shilling and eight pence from James Yoohooson", or "as of this Wednesday, Lance Alot owes sixpence to Sir Robin").

Definitions

Enough history for now. Let's stop for a minute, and get some basic definitions clear.

First and foremost, the most basic question of all, but one that surprisingly few people have ever actually stopped to think about: what is money?

There are numerous answers:

Money is a medium of exchange.

Source: The Privateer - What is money?

Money itself … is useless until the moment we use it to purchase or invest in something. Although money feels as if it has an objective value, its worth is almost completely subjective.

Source: Forbes - Money! What is it good for?

As with other things, necessity is, indeed, the mother of invention. People needed a formula of stating the standard value of trade goods.

Thus, money was born.

Source: The Daily Bluster - Where did money come from, anyway?

The seller and the depositor alike receive a credit, the one on the official bank and the other direct on the government treasury, The effect is precisely the same in both cases. The coin, the paper certificates, the bank-notes and the credit on the books of the bank, are all indentical in their nature, whatever the difference of form or of intrinsic value. A priceless gem or a worthless bit of paper may equally be a token of debt, so long as the receiver knows what it stands for and the giver acknowledges his obligation to take it back in payment of a debt due.

Money, then, is credit and nothing but credit. A's money is B's debt to him, and when B pays his debt, A's money disappears. This is the whole theory of money.

Source: What is Money?

Original source: The Banking Law Journal, May 1913, By A. Mitchell Innes.

Image source: DuckTales…Woo-ooo!

I think the first definition is the easiest to understand. Money is a medium of exchange: it has no value in and of itself; but it allows us to more easily exchange between ourselves, things that do have value.

I think the last definition, however, is the most honest. Money is credit: or, to be more correct, money is a type of credit; a credit that is expressed in a uniform, easily quantifiable / divisible / exchangeable unit of measure (as opposed to a credit that's expressed in goats, or in bushels of wheat).

(Note: the idea of money as credit, and of credit as debt, comes from the credit theory of money, which was primarily formulated by Innes (quoted above). This is just one theory of money. It's not the definitive theory of money. However, I tend to agree with the theory's tenets, and various parts of the rest of this article are founded on the theory. Also, it should not be confused with The Theory of Money and Credit, a book from the Austrian School of economics, which asserts that the only true money is commodity money, and which is thus pretty well the opposite extreme from the credit theory of money.)

Which brings us to the next defintion: what is credit?

In the article giving the definition of "money as credit", it's also mentioned that "credit" and "debt" are effectively the same thing; just that the two words represent the two sides of a single relationship / transaction. So, then, perhaps it would make more sense to define what is debt:

Middle English dette: from Old French, based on Latin debitum 'something owed', past participle of debere 'owe'.

Source: Oxford dictionaries: debt.

A debt is something that one owes; it is one's obligation to give something of value, in return for something that one received.

Conversely, a credit is the fact of one being owed something; it is a promise that one has from another person / entity, that one will be given something of value in the future.

So, then, if we put the two definitions together, we can conclude that: money is nothing more than a promise, from the person / entity who issued the money, that they will give something of value in the future, to the current holder of the money.

Perhaps the simplest to understand example of this, in the modern world, is the gift card typically offered by retailers. A gift card has no value itself: it's nothing more than a promise by the retailer, that they will give the holder of the card a shirt, or a DVD, or a kettle. When the card holder comes into the shop six months later, and says: "I'd like to buy that shirt with this gift card", what he/she really means is: "I have here a written promise from you folks, that you will give me a shirt; I am now collecting what was promised". Once the shirt has been received, the gift card is suddenly worthless, as the documented promise has been fulfilled; this is why, when the retailer reclaims the gift card, they usually just dispose of it.

However, there is one important thing to note: the only value of the gift card, is that it's a promise of being exchangeable for something else; and as long as that promise remains true, the gift card has value. In the case of a gift card, the promise ceases to be true the moment that you receive the shirt; the card itself returns to its original issuer (the retailer), and the story ends there.

Money works the same way, only with one important difference: it's a promise from the government, of being exchangeable for something else; and when you exchange that money with a retailer, in return for a shirt, the promise remains true; so the money still has value. As long as the money continues to be exchanged between regular citizens, the money is not returned to its original issuer, and so the story continues.

So, as with a gift card: the moment that money is returned to its original issuer (the government), that money is suddenly worthless, as the documented promise has been fulfilled. What do we usually return money to the government for? Taxes. What did the government originally promise us, by issuing money to us? That it would take care of us (it doesn't buy us flowers or send us Christmas cards very often; it demonstrates its caring for us mainly with other things, such as education and healthcare). What happens when we pay taxes? The government takes care of us for another year (it's supposed to, anyway). Therefore, the promise ceases to be true; and, believe it or not, the moment that the government reclaims the money in taxes, that money ceases to exist.

The main thing that a government promises, when it issues money, is that it will take care of its citizens; but that's not the only promise of money. Prior to quite recent times, money was based on gold: people used to give their gold to the government, and in return they received money; so, money was a promise that the government would give you back your gold, if you ever wanted to swap again.