Company rule, and the subsequent rule of the British Raj, are also acknowledged as contributing positively to the shaping of Modern India, having introduced the English language, built the railways, and established political and military unity. But these are overshadowed by its legacy of corporate greed and wholesale plunder, which continues to haunt the region to this day.

I recently read Four Heroes of India (1898), by F.M. Holmes, an antique book that paints a rose-coloured picture of Company (and later British Government) rule on the Subcontinent. To the modern reader, the book is so incredibly biased in favour of British colonialism that it would be hilarious, were it not so alarming. Holmes's four heroes were notable military and government figures of 18th and 19th century British India.

Image source: eBay.

I'd like to present here four alternative heroes: men (yes, sorry, still all men!) who in my opinion represented the British far more nobly, and who left a far more worthwhile legacy in India. All four of these figures were founders or early members of The Asiatic Society (of Bengal), and all were pioneering academics who contributed to linguistics, science, and literature in the context of South Asian studies.

William Jones

The first of these four personalities was by far the most famous and influential. Sir William Jones was truly a giant of his era. The man was nothing short of a prodigy in the field of philology (which is arguably the pre-modern equivalent of linguistics). During his productive life, Jones is believed to have become proficient in no less than 28 languages, making him quite the polyglot:

Eight languages studied critically: English, Latin, French, Italian, Greek, Arabic, Persian, Sanscrit [sic]. Eight studied less perfectly, but all intelligible with a dictionary: Spanish, Portuguese, German, Runick [sic], Hebrew, Bengali, Hindi, Turkish. Twelve studied least perfectly, but all attainable: Tibetian [sic], Pâli [sic], Pahlavi, Deri …, Russian, Syriac, Ethiopic, Coptic, Welsh, Swedish, Dutch, Chinese. Twenty-eight languages.

Source: Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Correspondence, of Sir William Jones, John Shore Baron Teignmouth, 1806, Page 376.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Jones is most famous in scholarly history for being the person who first proposed the linguistic family of Indo-European languages, and thus for being one of the fathers of comparative linguistics. His work laid the foundations for the theory of a Proto-Indo-European mother tongue, which was researched in-depth by later linguists, and which is widely accepted to this day as being a language that existed and that had a sizeable native speaker population (despite there being no concrete evidence for it).

Jones spent 10 years in India, working in Calcutta as a judge. During this time, he founded The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Jones was the foremost of a loosely-connected group of British gentlemen who called themselves orientalists. (At that time, "oriental studies" referred primarily to India and Persia, rather than to China and her neighbours as it does today.)

Like his peers in the Society, Jones was a prolific translator. He produced the authoritative English translation of numerous important Sanskrit documents, including Manu Smriti (Laws of Manu), and Abhiknana Shakuntala. In the field of his "day job" (law), he established the right of Indian citizens to trial by jury under Indian jurisprudence. Plus, in his spare time, he studied Hindu astronomy, botany, and literature.

James Prinsep

The numismatist James Prinsep, who worked at the Benares (Varanasi) and Calcutta mints in India for nearly 20 years, was another of the notable British orientalists of the Company era. Although not quite in Jones's league, he was nevertheless an intelligent man who made valuable contributions to academia. His life was also unfortunately short: he died at the age of 40, after falling sick of an unknown illness and failing to recover.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Prinsep was the founding editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He is best remembered as the pioneer of numismatics (the study of coins) on the Indian Subcontinent: in particular, he studied numerous coins of ancient Bactrian and Kushan origin. Prinsep also worked on deciphering the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts; and he contributed to the science of meteorology.

Charles Wilkins

The typographer Sir Charles Wilkins arrived in India in 1770, several years before Jones and most of the other orientalists. He is considered the first British person in Company India to have mastered the Sanskrit language. Wilkins is best remembered as having created the world's first Bengali typeface, which became a necessity when he was charged with printing the important text A Grammar of the Bengal Language (the first book written in Bengali to ever be printed), written by fellow orientalist Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, and more-or-less commissioned by Governor Warren Hastings.

It should come as no surprise that this pioneering man was one of the founders of The Asiatic Society of Bengal. Like many of his colleagues, Wilkins left a proud legacy as a translator: he was the first person to translate into English the Bhagavad Gita, the most revered holy text in all of Hindu lore. He was also the first director of the "India Office Library".

H. H. Wilson

The doctor Horace Hayman Wilson was in India slightly later than the other gentlemen listed here, not having arrived in India (as a surgeon) until 1808. Wilson was, for a part of his time in Company India, honoured with the role of Secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Wilson was one of the key people to continue Jones's great endeavour of bridging the gap between English and Sanskrit. His key contribution was writing the world's first comprehensive Sanskrit-English dictionary. He also translated the Meghaduuta into English. In his capacity as a doctor, he researched and published on the matter of traditional Indian medical practices. He also advocated for the continued use of local languages (rather than of English) for instruction in Indian native schools.

The legacy

There you have it: my humble short-list of four men who represent the better side of the British presence in Company India. These men, and other orientalists like them, are by no means perfect, either. They too participated in the Company's exploitative regime. They too were part of the ruling elite. They were no Mother Teresa (the main thing they shared in common with her was geographical location). They did little to help the day-to-day lives of ordinary Indians living in poverty.

Nevertheless, they spent their time in India focused on what I believe were noble endeavours; at least, far nobler than the purely military and economic pursuits of many of their peers. Their official vocations were in administration and business enterprise, but they chose to devote themselves as much as possible to academia. Their contributions to the field of language, in particular – under that title I include philology, literature, and translation – were of long-lasting value not just to European gentlemen, but also to the educational foundations of modern India.

In recent times, the term orientalism has come to be synonymous with imperialism and racism (particularly in the context of the Middle East, not so much for South Asia). And it is argued that the orientalists of British India were primarily concerned with strengthening Company rule by extracting knowledge, rather than with truly embracing or respecting India's cultural richness. I would argue that, for the orientalists presented here at least, this was not the case: of course they were agents of British interests, but they also genuinely came to respect and admire what they studied in India, rather than being contemptuous of it.

The legacy of British orientalism in India was, in my opinion, one of the better legacies of British India in general. It's widely acknowledged that it had a positive long-term educational and intellectual effect on the Subcontinent. It's also a topic about which there seems to be insufficient material available – particularly regarding the biographical details of individual orientalists, apart from Jones – so I hope this article is useful to anyone seeking further sources.

]]>To start with, let's focus on the more common and important meanings of these words. The most fundamental meaning of "on" and "off", is to describe something as being situated (or not situated) atop something else. E.g: "the dog is on the mat", and "the box is off the carpet". "On" can also describe something as being stuck to or hanging from something else. E.g: "my tattoo is on my shoulder", "the painting is on the wall". (To describe the reverse of this, it's best to simply say "not on", as saying "off" would imply that the painting has fallen off — but let's not go there just yet!).

"On" and "off" also have the fundamental meaning of describing something as being activated (or de-activated). This can be in regard to electrical objects, e.g: "the light is on / off", or simply "it's on / off". It can also be in regard to events, e.g: "your favourite TV show is on now". For the verb form of activating / de-activating something, simply use the expressions: "turn it on / off".

But from these simple beginnings… my, oh my, how much more there is to learn! Let's dive into some expressions that make use of "on" and "off".

Bored this weekend? Maybe you should ask your mates: "what's on?" Maybe you're thinking about going to Fiji next summer — if so: "it's on the cards". And when you finally do get over there, let your folks know: "I'm off!". And make sure your boss has given you: "the week off". If you're interested in Nigerian folk music, you might be keeping it: "on your radar". After 10 years spreading the word about your taxidermy business, everyone finally knows about it: "you're on the map". And hey, your services are "on par" with any other stuffed animal enterprise around.

Or we could get a bit saucier with our expressions. Next time you chance to see a hottie at yer local, let her know: "you turn me on". Or if she just doesn't do it for you: "she turns me off" (don't say it to her face). Regarding those sky-blue eyes, or that unsightly zit, respectively: "what a turn-on / what a turn-off". After a few drinks, maybe you'll pluck up the courage to announce: "let's get it on". And later on, in the bedroom — who knows? You may even have occasion to comment: "that gets me off".

And the list "goes on". When you're about to face the music, you tell the crew: "we're on". When it's you're shout, tell your mates: "drinks are on me". When you've had a bad day at work, you might want to whinge to someone, and: "get it off your chest". When you call auntie Daisy for her birthday, she'll probably start: "crapping on and on". When you smell the milk in the fridge, you'll know whether or not it's: "gone off".

Don't believe the cops when they tell you that your information is strictly: "off the record". And don't let them know that you're "off your face" on illicit substances, either. They don't take kindly to folks who are: "high on crack". So try and keep the conversation: "off-topic". No need for everything in life to stay: "on track". In the old days, of course, if you got up to any naughty business like that, it was: "off with your head!".

If you're into soccer, you'll want to "kickoff" to get the game started. But be careful you don't stray: "offside". If you can't "get a handle on" those basics, you might be "better off" playing something else. Like croquet. Or joining a Bob Sinclair tribute band, and singing: "World, Hold On".

That's about all the examples I can think of for now. I'm sure there are more, though. Feel free to drop a comment with your additional uses of "on" and "off", exposed once and for all as two words in the English language that "get around" more than most.

]]>Of the languages that have influenced the development of English over the years, there are three whose effect can be overwhelmingly observed in modern English: French ("Old Norman"), Latin, and Germanic (i.e. "Old English"). But what about Celtic? It's believed that the majority of England's pre-Anglo-Saxon population spoke Brythonic (i.e. British Celtic). It's also been recently asserted that the majority of England's population today is genetically pre-Anglo-Saxon Briton stock. How, then — if those statements are both true — how can it be that the Celtic languages have left next to no legacy on modern English?

The Celtic Question — or "Celtic Puzzle", as some have called it — is one that has spurred heated debate and controversy amongst historians for many years. The traditional explanation of the puzzle, is the account of the Germanic migration to Britain, as given in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. As legend has it, in the year 449 C.E., two Germanic brothers called Hengest and Horsa were invited to Britain by Vortigern (King of the Britons) as mercenaries. However, after helping the Britons in battle, the two brothers murdered Vortigern, betrayed the Britons, and paved the way for an invasion of the land by the Germanic tribes the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes.

Over the subsequent centuries, the Britons were either massacred, driven into exile, or subdued / enslaved. Such was the totality of the invasion, that aside from geographical place-names, virtually no traces of the old Brythonic language survived. The invaded land came to be known as "England", deriving from "Angle-land", in honour of the Angles who were one of the chief tribes responsible for its inception.

Various historians over the years have suggested that the Anglo-Saxons committed genocide on the indigenous Britons that failed to flee England (those that did flee went to Wales, Cornwall, Cumbria and Brittany). This has always been a contentious theory, mainly because there is no historical evidence to support any killings on a scale necessary to constitute "genocide" in England at this time.

More recently, the geneticist Stephen Oppenheimer has claimed that the majority of English people today are the descendants of indigenous Britons. Oppenheimer's work, although being far from authoritative at this time (many have criticised its credibility), is nevertheless an important addition to the weight of the argument that a large-scale massacre of the Celtic British people did not occur.

(Unfortunately, Oppenheimer has gone beyond his field of expertise,which is genetics, and has drawn conclusions on the linguistic history of Britain — namely, he argues that the pre-Roman inhabitants of England were not Celtic speakers, but that they were instead Germanic speakers. This argument is completely flawed from an academic linguistic perspective; and sadly, as a consequence, Oppenheimer's credibility in general has come to be questioned.)

Explanations to the riddle

Although the Celtic Question may seem like a conundrum, various people have come up with logical, reasonable explanations for it. One such person is Geoffrey Sampson, who has written a thorough essay about the birth of the English language. Sampson gives several sound reasons why Celtic failed to significantly influence the Anglo-Saxon language at the time of the 5th century invasions. His first reason is that Celtic and Germanic are two such different language groups, that they were too incompatible to easily mix and merge:

The Celtic languages… are very different indeed from English. They are at least as "alien" as Russian, or Greek, say.

His second reason is that, while many Britons surely did remain in the conquered areas of England, a large number must have also "run to the hills":

But when we add the lack of Celtic influence on the language, perhaps the most plausible explanation is an orderly retreat by the ancient Britons, men women and children together, before invaders that they weren't able to resist. Possibly they hoped to regroup in the West and win back the lands they had left, but it just never happened.

I also feel compelled to note that while Sampson is a professor and his essay seems reasonably well-informed, I found a rather big blotch to his name. He was accused of expressing racism, after publishing another essay on his web site entitled "There's Nothing Wrong with Racism". This incident seems to have cut short the aspirations that he had of pursuing a career in politics. Also, even before doing the background research and unearthing that incident, I felt suspicion stirring within me when I read this line, further down in his essay on the English language, regarding the Battle of Hastings:

The battle today is against a newer brand of Continental domination.

That sounds to me like the remark of an unashamed typical old-skool English xenophobiac. Certainly, anyone who makes remarks like that, is someone I'd advise listening to with a liberal grain of salt.

Another voice on this topic is Claire Lovis, who has written a great balanced piece regarding the Celtic influence on the English language. Lovis makes an important point when she remarks on the stigmatisation of Celtic language and culture by the Anglo-Saxons:

The social stigma attached to the worth of Celtic languages in British society throughout the last thousand years seems responsible for the dearth of Celtic loan words in the English language… Celtic languages were viewed as inferior, and words that have survived are usually words with geographical significance, and place names.

Lovis re-iterates, at the end of her essay, the argument that the failure of the Celtic language to influence English was largely the result of its being looked down upon by the ruling invaders:

The lack of apparent word sharing is indicative of how effective a social and political tool language can be by creating a class system through language usage… the very social stigma that suppressed the use of Celtic language is the same stigma that prevents us learning the full extent of the influence those languages have had on English.

The perception of Celtic language and culture as "inferior" can, of course, be seen in the entire 1,000-year history of England's attitudes and treatment towards her Celtic neighbours, particularly in Scotland and Ireland. The Ango-Saxon medieval (and even modern) England consistently displayed contempt and intolerance towards those with a Celtic heritage, and this continues — at least to some extent — even to the present day.

My take on the question

I agree with the explanations given by Sampson and Lovis, namely that:

- Celtic was "alien" to the Anglo-Saxon language, hence it was a question of one language dominating over the other, with a mixed language being an unlikely outcome

- Many Celtic people fled England, and those that remained were in no position to preserve their language or culture

- Celtic was stigmatised by the Anglo-Saxons over a prolonged period of time, thus strongly encouraging the Britons to abandon their old language and to wholly embrace the language of the invaders

The strongest parallel that I can think of for this "Celtic death" in England, is the Spanish conquest of the Americas. In my opinion, the imposition of Spanish language and culture upon the various indigenous peoples of the New World in the 16th century — in particular, upon the Aztecs and the Mayans in Mexico — seems very similar to the situation with the Germanics and the Celtics in the 5thcentury:

- The Spanish language and the native American languages were completely "alien" to each other, leaving little practical possibility of the languages easily fusing (although I'd say that, in Mexico in particular, indigenous language actually managed to infiltrate Spanish much more effectively than Celtic ever managed to infiltrate English)

- The natives of the New World either fled the conquistadores, or they were enslaved / subdued (or, of course, they died — mostly from disease)

- The indigenous languages and cultures were heavily stigmatised and discouraged (in the case of the Spanish inquisition, on pain of death — probably more extreme than what happened at any time during the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain), thus strongly encouraging the acceptance of the Spanish language (and, of course, the Catholic Church)

In Mexico today, the overwhelming majority of the population is classified as being ethnically "mestizo" (meaning "mixture"), with the genetics of the mestizos tending generally towards the indigenous side. That is, the majority of Mexicans today are of indigenous stock. And yet, the language and culture of modern Mexico are almost entirely Spanish, with indigenous languages all but obliterated, and with indigenous cultural and religious rites severely eroded (in the colonial heartland, that is — in the jungle areas, in particular the Mayan heartland of the south-east, indigenous language and culture remains relatively strong to the present day).

Mexico is a comparatively modern and well-documented example of an invasion, where the aftermath is the continuation of an indigenous genetic majority, coupled with the near-total eradication of indigenous language. By looking at this example, it isn't hard to imagine how a comparable scenario could have unfolded (and most probably did unfold) 1,100 years earlier in Britain.

There doesn't appear to be any parallel in terms of religious stigmatisation — certainly nothing like the Spanish Inquisition occurred during the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain, and to suggest as much would be ludicrous — and all of Britain was swept by a wave of Christianity just a few centuries after, anyway (and no doubt the Anglo-Saxon migrations were still occurring while Britain was being converted en masse away from both Celtic and Germanic paganism). There's also no way to know whether the Britons were forcibly indoctrinated with the Anglo-Saxon language and culture — by way of breaking up families, stealing children, imposing changes on pain of death, and so on — or whether they embraced the Anglo-Saxon language and culture of their own volition, under the sheer pressure of stigmatisation and the removal of economic / social opportunity for those who resisted change. Most likely, it was a combination of both methods, varying between places and across time periods.

The Brythonic language is now long since extinct, and the fact is that we'll never really know how it was that English came to wholly displace it, without being influenced by it to any real extent other than the preservation of a few geographical place names (and without the British people themselves disappearing genetically). The Celtic question will likely remain unsolved, possibly forever. But considering that modern English is the world's first de facto global lingua franca (not to mention the native language of hundreds of millions of people, myself included), it seems only right that we should explore as much as we can into this particularly dark aspect of our language's origins.

]]>The raw data

Fact: Unicode's "codespace" can represent up to 1,114,112 characters in total.

Fact: As of today, 100,540 of those spaces are in use by assigned characters (excluding private use characters).

The Unicode people provide a plain text listing of all supported Unicode scripts, and the number of assigned characters in each of them. I used this listing in order to compile a table of assigned character counts grouped by script. Most of the hard work was done for me. The table is almost identical to the one you can find on the Wikipedia Unicode scripts page, except that this one is slightly more updated (for now!).

| Unicode script name | Category | ISO 15924 code | Number of characters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Miscellaneous | Zyyy | 5178 |

| Inherited | Miscellaneous | Qaai | 496 |

| Arabic | Middle Eastern | Arab | 999 |

| Armenian | European | Armn | 90 |

| Balinese | South East Asian | Bali | 121 |

| Bengali | Indic | Beng | 91 |

| Bopomofo | East Asian | Bopo | 65 |

| Braille | Miscellaneous | Brai | 256 |

| Buginese | South East Asian | Bugi | 30 |

| Buhid | Philippine | Buhd | 20 |

| Canadian Aboriginal | American | Cans | 630 |

| Carian | Ancient | Cari | 49 |

| Cham | South East Asian | Cham | 83 |

| Cherokee | American | Cher | 85 |

| Coptic | European | Copt | 128 |

| Cuneiform | Ancient | Xsux | 982 |

| Cypriot | Ancient | Cprt | 55 |

| Cyrillic | European | Cyrl | 404 |

| Deseret | American | Dsrt | 80 |

| Devanagari | Indic | Deva | 107 |

| Ethiopic | African | Ethi | 461 |

| Georgian | European | Geor | 120 |

| Glagolitic | Ancient | Glag | 94 |

| Gothic | Ancient | Goth | 27 |

| Greek | European | Grek | 511 |

| Gujarati | Indic | Gujr | 83 |

| Gurmukhi | Indic | Guru | 79 |

| Han | East Asian | Hani | 71578 |

| Hangul | East Asian | Hang | 11620 |

| Hanunoo | Philippine | Hano | 21 |

| Hebrew | Middle Eastern | Hebr | 133 |

| Hiragana | East Asian | Hira | 89 |

| Kannada | Indic | Knda | 84 |

| Katakana | East Asian | Kana | 299 |

| Kayah Li | South East Asian | Kali | 48 |

| Kharoshthi | Central Asian | Khar | 65 |

| Khmer | South East Asian | Khmr | 146 |

| Lao | South East Asian | Laoo | 65 |

| Latin | European | Latn | 1241 |

| Lepcha | Indic | Lepc | 74 |

| Limbu | Indic | Limb | 66 |

| Linear B | Ancient | Linb | 211 |

| Lycian | Ancient | Lyci | 29 |

| Lydian | Ancient | Lydi | 27 |

| Malayalam | Indic | Mlym | 95 |

| Mongolian | Central Asian | Mong | 153 |

| Myanmar | South East Asian | Mymr | 156 |

| N'Ko | African | Nkoo | 59 |

| New Tai Lue | South East Asian | Talu | 80 |

| Ogham | Ancient | Ogam | 29 |

| Ol Chiki | Indic | Olck | 48 |

| Old Italic | Ancient | Ital | 35 |

| Old Persian | Ancient | Xpeo | 50 |

| Oriya | Indic | Orya | 84 |

| Osmanya | African | Osma | 40 |

| Phags-pa | Central Asian | Phag | 56 |

| Phoenician | Ancient | Phnx | 27 |

| Rejang | South East Asian | Rjng | 37 |

| Runic | Ancient | Runr | 78 |

| Saurashtra | Indic | Saur | 81 |

| Shavian | Miscellaneous | Shaw | 48 |

| Sinhala | Indic | Sinh | 80 |

| Sundanese | South East Asian | Sund | 55 |

| Syloti Nagri | Indic | Sylo | 44 |

| Syriac | Middle Eastern | Syrc | 77 |

| Tagalog | Philippine | Tglg | 20 |

| Tagbanwa | Philippine | Tagb | 18 |

| Tai Le | South East Asian | Tale | 35 |

| Tamil | Indic | Taml | 72 |

| Telugu | Indic | Telu | 93 |

| Thaana | Middle Eastern | Thaa | 50 |

| Thai | South East Asian | Thai | 86 |

| Tibetan | Central Asian | Tibt | 201 |

| Tifinagh | African | Tfng | 55 |

| Ugaritic | Ancient | Ugar | 31 |

| Vai | African | Vaii | 300 |

| Yi | East Asian | Yiii | 1220 |

Regional and other groupings

The only thing that I added to the above table myself, was the data in the "Category" column. This data comes from the code charts page of the Unicode web site. This page lists all of the scripts in the current Unicode standard, and it groups them into a number of categories, most of which describe the script's regional origin. As far as I can tell, nobody's collated these categories with the character-count data before, so I had to do it manually.

Into the "Miscellaneous" category, I put the "Common" and the "Inherited" scripts, which contain numerous characters that are shared amongst multiple scripts (e.g. accents, diacritical marks), as well as a plethora of symbols from many domains (e.g. mathematics, music, mythology). "Common" also contains the characters used by the IPA. Additionally, I put Braille (the "alphabet of bumps" for blind people) and Shavian (invented phonetic script) into "Miscellaneous".

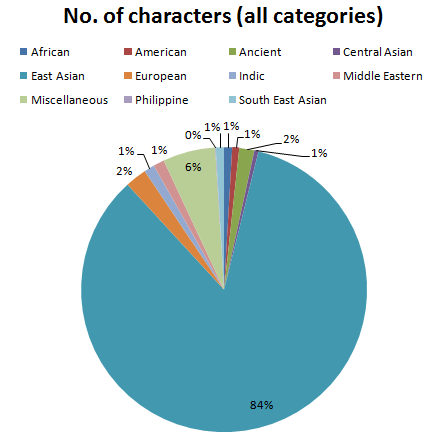

From the raw data, I then generated a summary table and a pie graph of the character counts for all the scripts, grouped by category:

| Category | No of characters | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| African | 915 | 0.91% |

| American | 795 | 0.79% |

| Ancient | 1724 | 1.71% |

| Central Asian | 478 | 0.48% |

| East Asian | 84735 | 84.28% |

| European | 2455 | 2.44% |

| Indic | 1185 | 1.18% |

| Middle Eastern | 1254 | 1.25% |

| Miscellaneous | 5978 | 5.95% |

| Philippine | 79 | 0.08% |

| South East Asian | 942 | 0.94% |

Attack of the Han

Looking at this data, I can't help but gape at the enormous size of the East Asian character grouping. 84.3% of the characters in Unicode are East Asian; and of those, the majority belong to the Han script. Over 70% of Unicode's assigned codespace is occupied by a single script — Han! I always knew that Chinese contained thousands upon thousands of symbols; but who would have guessed that their quantity is great enough to comprise 70% of all language symbols in known linguistic history? That's quite an achievement.

And what's more, this is a highly reduced subset of all possible Han symbols, due mainly to the Han unification effort that Unicode imposed on the script. Han unification has resulted in all the variants of Han — the notable ones being Chinese, Japanese, and Korean — getting represented in a single character set. Imagine the size of Han, were its Chinese / Japanese / Korean variants represented separately — no wonder (despite the controversy and the backlash) they went ahead with the unification!

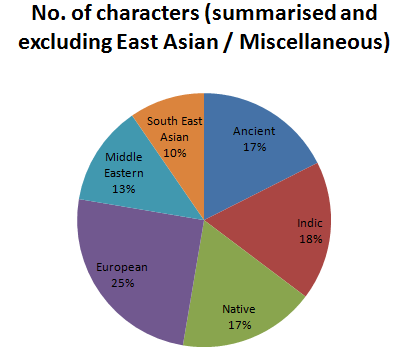

Broader groupings

Due to its radically disproportionate size, the East Asian script category squashes away virtually all the other Unicode script categories into obscurity. The "Miscellaneous" category is also unusually large (although still nowhere near the size of East Asian). As such, I decided to make a new data table, but this time with these two extra-large categories excluded. This allows the size of the remaining categories to be studied a bit more meaningfully.

For the remaining categories, I also decided to do some additional grouping, to further reduce disproportionate sizes. These additional groupings are my own creation, and I acknowledge that some of them are likely to be inaccurate and not popular with everyone. Anyway, take 'em or leave 'em: there's nothing official about them, they're just my opinion:

- I grouped the "African" and the "American" categories into a broader "Native" grouping: I know that this word reeks of arrogant European colonial connotations, but nevertheless, I feel that it's a reasonable name for the grouping. If you are an African or a Native American, then please treat the name academically, not personally.

- I also brought the "Indic", "Central Asian", and "Philippine" categories together into an "Indic" grouping. I did this because, after doing some research, it seems that the key Central Asian scripts (e.g. Mongolian, Tibetan) and the pre-European Philippine scripts (e.g. Tagalog) both have clear Indic roots.

- I left the "Ancient", "South-East Asian", "European" and "Middle Eastern" groupings un-merged, as they don't fit well with any other group, and as they're reasonably well-proportioned on their own.

Here's the data for the broader groupings:

| Grouping | No of characters | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient | 1724 | 17.54% |

| Indic | 1742 | 17.73% |

| Native | 1710 | 17.40% |

| European | 2455 | 24.98% |

| Middle Eastern | 1254 | 12.76% |

| South-Eastern | 942 | 9.59% |

And there you have it: a breakdown of the number of characters in the main written scripts of the world, as they're represented in Unicode. European takes the lead here, with the Latin script being the largest in the European group by far (mainly due to the numerous variants of the Latin alphabet, with accents and other symbols used to denote regional languages). All up, a relatively even spread.

I hope you find this interesting — and perhaps even useful — as a visualisation of the number of characters that the world's main written scripts employ today (and throughout history). If you ever had any doubts about the sheer volume of symbols used in East Asian scripts (but remember that the vast majority of them are purely historic and are used only by academics), then those doubts should now be well and truly dispelled.

It will also be interesting to see how this data changes, over the next few versions of Unicode into the future. I imagine that only the more esoteric categories will grow: for example, ever more obscure scripts will no doubt be encoded and will join the "Ancient" category; and my guess is that ever more bizarre sets of symbols will join the "Miscellaneous" category. There may possibly be more additions to the "Native" category, although the discovery of indigenous writing systems is far less frequent than the discovery of indigenous oral languages. As for the known scripts of the modern world, I'd say they're well and truly covered already.

]]>I'm now going to dive straight into a comparison of statutory language and programming code, by picking out a few examples of concepts that exist in both domains with differing names and differing forms, but with equivalent underlying purposes. I'm primarily using concept names from the programming domain, because that's the domain that I'm more familiar with. Hopefully, if legal jargon is more your thing, you'll still be able to follow along reasonably well.

Boolean operators

In the world of programming, almost everything that computers can do is founded on three simple Boolean operations: AND, OR, and NOT. The main use of these operators is to create a compound condition — i.e. a condition that can only be satisfied by meeting a combination of criteria. In legislation, Boolean operators are used just as extensively as they are in programming, and they also form the foundation of pretty much any statement in a unit of law. They even use exactly the same three English words.

In law:

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 1989 (NSW)

Transfer of applications

Section 20: Transfer of applications

- An agency to which an application has been made may transfer the application to another agency:

- if the document to which it relates:

- is not held by the firstmentioned agency but is, to the knowledge of the firstmentioned agency, held by the other agency, or

- is held by the firstmentioned agency but is more closely related to the functions of the other agency, and

- if consent to the application being transferred is given by or on behalf of the other agency.

- if the document to which it relates:

(from AustLII: NSW Consolidated Acts)

In code:

<?php

if (

(

($document->owner != $first_agency->name && $document->owner == $other_agency->name)

||

($document->owner == $first_agency->name && $document->functions == $other_agency->functions)

)

&&

(

($consent_giver->name == $other_agency->name)

||

($consent_giver->name == $representing_agency->name)

)

) {

/* ... */

}

?>Defined types

Every unit of data (i.e. every variable, constant, etc) in a computer program has a type. The way in which a type is assigned to a variable varies between programming languages: sometimes it's done explicitly (e.g. in C), where the programmer declares each variable to be "of type x"; and sometimes it's done implicitly (e.g. in Python), where the computer decides at run-time (or at compile-time) what the type of each variable is, based on the data that it's given. Regardless of this issue, however, in all programming languages the types themselves are clearly and explicitly defined. Almost all languages also have primitive and structured data types. Primitive types usually include "integer", "float", "boolean" and "character" (and often "string" as well). Structured types consist of attributes, and each attribute is either of a primitive type, or of another structured type.

Legislation follows a similar pattern of clearly specifying the "data types" for its "variables", and of including definitions for each type. Variables can be of a number of different types in legislation, however "person" (and sub-types) is easily the most common. Most Acts contain a section entitled "definitions", and it's not called that for nothing.

In law:

SALES TAX ASSESSMENT ACT 1992 (Cth) No. 114

Section 5: General definitions

In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears:

...

- "eligible Australian traveller" means a person defined to be an eligible Australian traveller by regulations made for the purposes of this definition;

...

- "person" means any of the following:

- a company;

- a partnership;

- a person in a particular capacity of trustee;

- a body politic;

- any other person;

(from AustLII: Commonwealth Numbered Acts)

In code:

<?php

class Person {

protected PersonType personType;

/* ... */

}

class EligibleAustralianTraveller extends Person {

private RegulationSet regulationSet;

/* ... */

}

?>Also related to defined types is the concept of graphs. In programming, it's very common to think of a set of variables as nodes, which are connected to each other with lines (or "edges"). The connections between nodes often makes up a significant part of the definition of a structured data type. In legislation, the equivalent of nodes is people, and the equivalent of connecting lines is relationships. In accordance with the programming world, a significant part of most definitions in legislation are concerned with the relationship that one person has to another. For example, various government officers are defined as being "responsible for" those below them, and family members are defined as being "related to" each other by means such as marriage and blood.

Exception handling

Many modern programming languages support the concept of "exceptions". In order for a program to run correctly, various conditions need to be met; if one of those conditions should fail, then the program is unable to function as intended, and it needs to have instructions for how to deal with the situation. Legislation is structured in a similar way. In order for the law to be adhered to, various conditions need to be met; if one of those conditions should fail, then the law has been "broken", and consequences should follow.

Legislation is generally designed to "assume the worst". Law-makers assume that every requirement they dictate will fail to be met; that every prohibition they publish will be violated; and that every loophole they leave unfilled will be exploited. This is why, to many people, legislation seems to spend 90% of its time focused on "exception handling". Only a small part of the law is concerned with what you should do. The rest of it is concerned with what you should do when you don't do what you should do. Programming and legislation could certainly learn a lot from each other in this area — finding loopholes through legal grey areas is the equivalent of hackers finding backdoors into insecure systems, and legislation is as full of loopholes as programs are full of security vulnerabilities. Exception handling is also something that's not implemented particularly cleanly or maintainably in either domain.

In law:

HUMAN TISSUE ACT 1982 (Vic)

Section 24: Blood transfusions to children without consent

- Where the consent of a parent of a child or of a person having authority to consent to the administration of a blood transfusion to a child is refused or not obtained and a blood transfusion is administered to the child by a registered medical practitioner, the registered medical practitioner, or any person acting in aid of the registered medical practitioner and under his supervision in administering the transfusion shall not incur any criminal liability by reason only that the consent of a parent of the child or a person having authority to consent to the administration of the transfusion was refused or not obtained if-

- in the opinion of the registered medical practitioner a blood transfusion was-

- a reasonable and proper treatment for the condition from which the child was suffering; and

- in the opinion of the registered medical practitioner a blood transfusion was-

...

(from AustLII: Victoria Consolidated Acts)

In code:

<?php

class Transfusion {

public static void main() {

try {

this.giveBloodTransfusion();

}

catch (ConsentNotGivenException e) {

this.isDoctorLiable = e.isReasonableJustification;

}

}

private void giveBloodTransfusion() {

this.performTransfusion();

if (!this.consentGiven) {

throw new ConsentNotGivenException();

}

}

}

?>Final thoughts

The only formal academic research that I've found in this area is the paper entitled "Legislation As Logic Programs", written in 1992 by the British computer scientist Robert Kowalski. This was a fascinating project: it seems that Kowalski and his colleages were actually sponsored, by the British government, to develop a prototype reasoning engine capable of assisting people such as judges with the task of legal reasoning. Kowalski has one conclusion that I can't help but agree with wholeheartedly:

The similarities between computing and law go beyond those of linguistic style. They extend also to the problems that the two fields share of developing, maintaining and reusing large and complex bodies of linguistic texts. Here too, it may be possible to transfer useful techniques between the two fields.

(Kowalski 1992, part 7)

Legislation and computer programs are two resources that are both founded on the same underlying structures of formal logic. They both attempt to represent real-life, complex human rules and problems, in a form that can be executed to yield a Boolean outcome. And they both suffer chronically with the issue of maintenance: how to avoid bloat; how to keep things neat and modular; how to re-use and share components wherever possible; how to maintain a stable and secure library; and how to keep the library completely up-to-date and on par with changes in the "real world" that it's trying to reflect. It makes sense, therefore, that law-makers and programmers (traditionally not the most chummy of friends) really should engage in collaborative efforts, and that doing so would benefit both groups tremendously.

There is, of course, one very important thing that almost every law contains, and that judges must evaluate almost every day. One thing that no computer program contains, and that no CPU in the world is capable of evaluating. That thing is a single word. A word called "reasonable". People's fate as murderers or as innocents hinges on whether or not there's "reasonable doubt" on the facts of the case. Police are required to maintain a "resonable level" of law and order. Doctors are required to exercise "reasonable care" in the treatment of their patients. The entire legal systems of all the civilised world depend on what is possibly the most ambiguous and ill-defined word in the entire English language: "reasonable". And to determine reasonableness requires reasoning — the outcome is Boolean, but the process itself (of "reasoning") is far from a simple yes or no affair. And that's why I don't expect to see a beige-coloured rectangular box sitting in the judge's chair of my local court any time soon.

]]>A few days ago, I finished reading Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's famous book, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892). This was the first time that the famous detective's adventures had been published in a permanent tome, rather than in a more transient volume, such as a journal or a magazine. It contains 12 short stories of intrigue, perplexity, and 'logical deduction', and it was a great read.

But as I neared the end of this book, something about it suddenly struck me. There was something about the way it was written, which was profoundly different to the way that more recent books are usually written. It was more profound than simply the old-fashioned vocabulary, or than the other little hallmarks of the time, such as fashion, technology, politics, and class division. It was the heavy use of dialogue. In particular, the dialogue of characters speaking to each other when recalling past events. Take, for example, this quote from the 11th story in the book, The Beryl Coronet:

[Alexander Holder speaks] "Yesterday morning I was seated in my office at the bank, when a card was brought in to me by one of the clerks. I started when I saw the name, for it was that of none other than - well, perhaps even to you I had better say no more than that it was a name which is a household word all over the earth - one of the highest, noblest, most exalted names in England. I was overwhelmed by the honour, and attempted, when he entered, to say so, but he plunged at once into business with the air of a man who wishes to hurry quickly through a disagreeable task.

"'Mr Holder', said he, 'I have been informed that you are in the habit of advancing money.' ...

In this example, not only is the character (Mr Holder) reciting a past event, but he is even reciting a past conversation that he had with another character! To the modern reader, this should universally scream out at you: old fashioned! Why does the character have to do all this recitation? Why can't the author simply take us back to the actual event, and narrate it himself? If the same thing were being written in a modern book, it would probably read something like this:

Alexander Holder was seated in his office at the bank. It had been a busy morning, riddled with pesky clients, outstanding loans, and pompous inspectors. Holder was just about to get up and locate a fresh supply of tea, when one of his clerks bustled in, brandishing a small card.

He read the name. Not just any name: a name that almost every household in the land surely knows. One of the highest, noblest, most exalted names in England.

"Thankyou", Holder said curtly.

Before he even had a chance to instruct his clerk that the guest was to be ushered in immediately, the man entered of his own accord. Holder was overwhelmed by the honour, and attempted to say so; but he barely had time to utter one syllable, for his guest plunged at once into business, with the air of a man who wishes to hurry quickly through a disagreeable task.

"Mr Holder", said he, with a wry smile, "I have been informed that you are in the habit of advancing money." ...

This new, 'modernified' version of Doyle's original text probably feels much more familiar to the modern reader.

It is my opinion that Sherlock Holmes is written very much like a play. The number of characters 'on stage' is kept to a minimum, and dialogues with other characters are recalled rather than narrated. Most of the important substance of the story is enclosed within speech marks, with as little as possible being expounded by the narrator. I have read other 19th century novels that exhibit this same tendency, and really it should come as no surprise to anyone. After all, in those days the play was still considered the dominant literary form, with the novel being a fledgling new contender. Novelists, therefore, were very much influenced by the style and language of plays - many of them were, indeed, playwrights as well as novelists. Readers, in turn, would have felt comforted by a story whose language leaned towards that of the plays that many of them often watched.

My 'new version' of the story, however - which is written in a style used by many contemporary novels - exhibits a different deviation from the novel style. It is written more like a movie. In this style, emphasis is given to providing information through visual objects, such as scenery, costumes, and props. Physical dynamics of the characters, such as hand gestures and facial expressions, are described in greater detail. Parts of the story are told through these elements wherever possible, instead of through dialogue, which is kept fairly spartan. Once again, this should be no groundbreaking surprise, since movies are the most popular form in which to tell a story in the modern world. Modern novelists, therefore, and modern readers, are influenced by the movie style, and inevitably imbue it within the classic novel style.

So, in summary: novels used to be written like plays; now they're written like movies.

This brings us to the question: what is the true 'novel style', and just how common (or uncommon) is it?

By looking at the Wikipedia entry on 'Novel', it is obvious that the novel itself is an unstable and, frankly, indefinable form that has evolved over many centuries, and that has been influenced by a great many other literary and artistic forms. However, although the search for an exact definition for a novel is not a task that I feel capable of undertaking, I would like to believe that a 'true novel' is one that is not written in the style of any other form (such as a play or a movie), but that exhibits its own unique and unadulterated form.

Just how many 'true novels' there are, I cannot say. As a generalisation, most of the 'pulp fiction' paperback type books, of the past several decades, are probably written more like movies than like true novels. The greatest number of true novels have definitely been written from the early 20th century onwards, although some older authors, such as Charles Dickens, certainly managed to craft true novels as well. As for the questions of whether the pursuit of finding or writing 'true novels' is a worthwhile enterprise, or of whether the 'true novel' has a future or not, or even of whether or not it matters how 'pure' novels are: I have no answer for them, and I suspect that there is none.

But considering that the novel is my favourite and most oft-read literary form, and that it's probably yours too, I believe that it couldn't hurt to invest a few minutes of your life in considering issues such as these.

]]>Now, before you accuse me of boasting and of being arrogant, let me just make it clear that my writing does not magically materialise in my head in the sleek, refined form that is its finished state, as I will now explain. What happens is that without ever even realising it, I always correct and analyse my writing as I go, making sure that my first version is as near to final as can be. Essentially, as each word or sentence sprouts forth from my mind, it passes through a rigorous process of editing and correction, so that by the time it reaches the page, it has already evolved from raw idea, to crudely communicated language, to polished and sophisticated language.

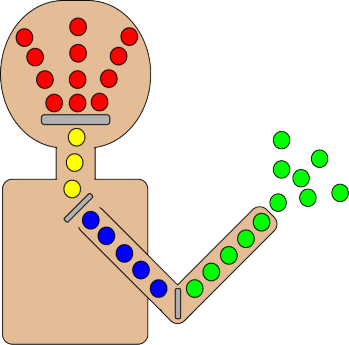

The diagram below illustrates this process:

The circular dots travelling through the body represent snippets of language. The grey-coloured barriers represent 'stations', at which all the snippets are reviewed and polished before being allowed to pass through. As the snippets pass through each barrier, their level of sheen improves (as indicated by the red, yellow, blue, and green colouring).

This is not something I ever chose to do. It wasn't through any ingenuity on my part, or on the part of anyone around me, that I wound up doing things like this. It's just the way my brain works. I'm a meticulous person: I can't cope with having words on the page that aren't presentable to their final audience. The mere prospect of it makes my hair turn grey and my ears droop (with only one of those two statements being true, at most ;-)). I'm also extremely impatient: I suspect that I learnt how to polish my words on-the-fly out of laziness; that is, I learnt because I dread ever having to actually read through my own crufty creation and undertake the rigour of improving it.

It recently occurred to me that I am incapable of writing in 'rough form'. I find it hard even to articulate 'rough words' within the privacy of my own head, let alone preserving that roughness through the entire journey from brain to fingertips. I am simply such a product of my own relentless régime, that I cannot break free from this self-imposed rigour.

Is this a blessing or a curse?

The advantages of this enforced rigour are fairly obvious. I never have to write drafts: as soon as I start putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard, as the case may be), I know that every word I write is final and is subject to only a cursory review later on. This is a tremendously useful skill to employ in exams, where editing time is a rare luxury, and where the game is best won by driving your nails home in one hit. In fact, I can't imagine how anyone could compose an extended answer under exam conditions, without adjusting their brain to work this way.

Dodging drafts is a joy even when time is not of the essence. For example, writing articles such as this one in my leisure time is a much less tedious and more efficient task, without the added hassle of extensive editing and fixing of mistakes.

However, although dodging drafts may appear to be a win-win strategy, I must assert from first-hand experience that it is not a strategy entirely without drawbacks. Not every single piece of writing that we compose in our daily lives is for public consumption. Many bits and pieces are composed purely for our own personal use: to-do lists, post-it notes, and mind maps are all examples of this.

Since these pieces of writing are not intended to be read by anyone other than the original author, there is no need to review them, or to produce a mistake-free final version thereof. But for me, there are no exceptions to the rigorous process of brain-to-fingertip on-the-fly reviewing. These writings are meant to be written in draft form; but I am compelled to write them in something much more closely resembling a presentable form! I am forced to expend more effort than is necessary on ensuring a certain level of quality in the language, and the result is a piece of writing that looks wrong and stupid.

For times like this, it would be great if I had a little switch inside my head, and if I could just turn my 'rigour filtering' on or off depending on my current needs. Sadly, no such switch is currently at my disposal, and despite all my years of shopping around, I have yet to find a manufacturer willing to produce one for me.

Making the first version the final version is an extremely useful skill, no doubt about it. I feel honoured and privileged to have been bestowed with this gift, and I don't wish for one second that I was without it. However, sometimes it would be nice if I was able to just 'let the words spew' from my fingers, without going to the trouble of improving their presentation whilst writing.

]]>What brought this to mind was my recent University results. My marks have been pretty good so far, during my time at uni: overall I've scored pretty highly. But there have been a few times, here and where, where I've slipped a bit below my standard. For those of you that don't know, the big thing that everyone's worried about at uni is their GPA (Grade Point Average), which is - as its name suggests - the mean of all your marks in all your subjects to date.

My GPA is pretty good (I ain't complaining), but it's a number that reflects my occasional slip-ups as clearly as it does my usual on-par performance. Basically, it's a mean number. It's a number that remembers every little bad thing you've done, so that no matter how hard you try to leave your mistakes behind you, they keep coming back to haunt you. It's a merciless number, based purely on facts and logic and cold, hard mathematics, with no room for leniency or compassion.

A mean makes me think of what (some people believe) happens when you die: your whole life is shown before you, the good and the bad; and all the little things are added up together, in order to calculate some final value. This value is the mean of your life's worth: all your deeds, good and bad, are aggregated together, for The Powers That Be to use in some almighty judgement. Of course, many people believe that this particular mean is subject to a scaling process, which generally turns out to be advantageous to the end number (i.e. the Lord is merciful, he forgives all sins, etc).

Mean is one of many words in the English language that are known as polysemes (polysemy is not to be confused with polygamy, which is an entirely different phenomenon!). A polyseme is a type of homonym (words that are spelt the same and/or sound the same, but have different meanings). But unlike other homonyms, a polyseme is one where the similarily in sound and/or spelling is not just co-incidental - it exists because the words have related meanings.

For example, the word 'import' is a homonym, because its two meanings ('import goods from abroad', and 'of great import') are unrelated. Although, for 'import', as for many other homonyms, it is possible to draw a loose connection between the meanings (e.g. perhaps 'of great import' came about because imported goods were historically usually more valuable / 'important' than local goods, or vice versa).

The word 'shot', on the other hand, is clearly a polyseme. As this amusing quote on the polyseme 'shot' demonstrates, 'a shot of whisky', 'a shot from a gun', 'a tennis shot', etc, are all related semantically. I couldn't find a list of polysemes on the web, but this list of heteronyms / homonyms (one of many) has many words that are potential candidates for being polysemes. For example, 'felt' (the fabric, and the past tense of 'feel') could easily be related: perhaps the first person who 'felt' that material decided that it had a nice feeling, and so decided to name the material after that first impression response.

I couldn't find 'mean' listed anywhere as a polyseme. In fact, for some strange reason, I didn't even see it under the various lists of homonyms on the net - and it clearly is a homonym. But personally, I think it's both. Very few homonyms are clearly polysemes - for most the issue is debatable, and is purely a matter of speculation, impossible to prove (without the aid of a time machine, as with so many other things!) - but that's my $0.02 on the issue, anyway.

The movie Robin Hood: Men in Tights gives an interesting hypothesis on how and why one particular word in the English language is a polyseme. At the end of the movie, the evil villain King John is cast down by his brother, King Richard. In order to make a mockery of the evil king, Richard proclaims: "henceforth all toilets in the land shall be known as Johns". Unfounded humour, or a plausible explanation? Who knows?

There are surely many more homonyms in the English language that, like 'mean' and 'felt' and 'shot', are also polysemes. If any of you have some words that you'd like to nominate as polysemes, feel free. The more bizarre the explanation, the better.

]]>But have you ever stopped to think about what this proverb means? I mean, seriously: who the hell swings cats? Why would someone tell you that there isn't enough room to swing a cat somewhere? How do they know? Have they tried? Is it vitally important that the room is big enough to swing a cat in? If so, then whoever resides in that room:

- is somewhat disturbed; and

- shouldn't own a cat.

Now, correct me if I'm wrong - I'm more a dog person myself, so my knowledge of cats is limited - but my understanding has always been that swinging cats around in a circular arc (possibly repeatedly) is generally not a good idea. Unless your cat gets a bizarre sense of pleasure from being swung around, or your cat has suddenly turned vicious and you're engaged in mortal combat with it, or you've just had a really bad day and need to take your anger out on something that's alive (and that can't report you to the police), or there's some other extraneous circumstance, I would imagine that as a cat owner you generally wouldn't display your love and affection for your feline friend in this manner.

Picture this: someone's looking at an open house. They go up to the real estate agent, and ask: "excuse me, but is there enough room to swing a cat in here? You see, I have a cat, and I like to swing it - preferably in my bedroom, but any room will do - so it's very important that the main bedroom's big enough." I'm sure real estate agents get asked that one every day!

What would the response be? Perhaps: "well, this room's 5.4m x 4.2m, and the average arm is 50cm long from finger to shoulder, and the average cat is roughly that much again. So if you're going to be doing full swings, that's at least a 2m diameter you'll be needing. So yeah, there should be plenty of space for it in here!"

I'm guessing that this proverb dates back to medieval times, when tape measures were a rare commodity, and cats were in abundance. For lack of a better measuring instrument, it's possible that cats became the preferred method of checking that a room had ample space. After all, a room that you can swing a cat around in is fairly roomy. But on the flip side, they must have gone through a lot of cats back then.

Also, if swinging animals around is your thing, then it's clear that cats are the obvious way to go. Dogs dribble too much (saliva would fly around the room); birds would just flap away; rabbits are too small to have much fun with; and most of the other animals (e.g. horses, cows, donkeys) are too big for someone to even grab hold of their legs, let alone to get them off the ground. If someone told you that a room was big enough to swing a cow around in, it just wouldn't sound right. You'd wonder about the person saying it. You'd wonder about the room. You'd wonder about the physics of the whole thing. Basically, you'd become very concerned about all of the above.

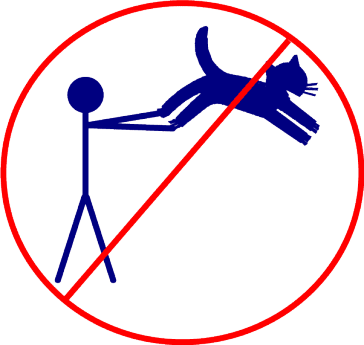

In case you know anyone who's in the habit of swinging cats, here's a little sign that you can stick on your bedroom door, just to let them know that funny business with cats is not tolerated in your corner of the world:

I hope that gives you a bit more of an insight into the dark, insidious world of cat swinging. Any comments or suggestions, feel free to leave them below.

]]>