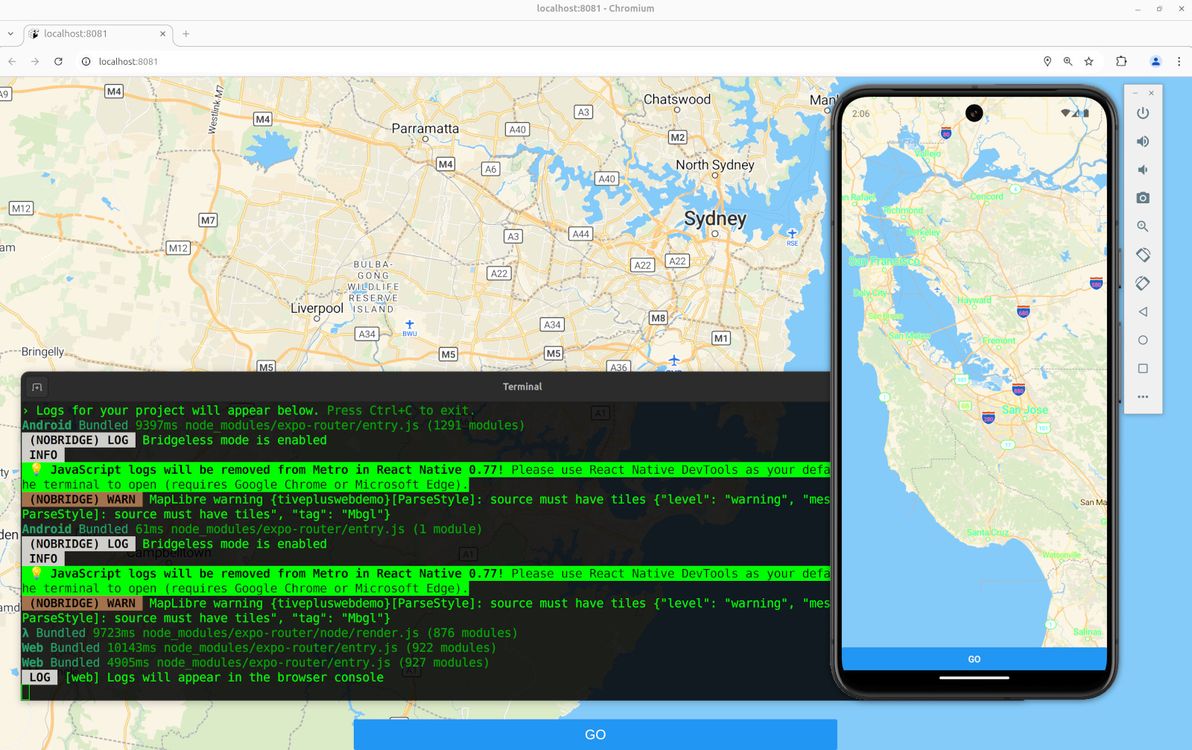

Below is my humble lil' guide to getting MapLibre working for both native and web in Expo. Note: if you want to skip the step-by-step shpiel, and you just want a working example with all the code, feel free to head straight to the Expo MapLibre native + web demo on GitHub.

Map library options

First of all, a quick rundown of the options that one has at one's disposal, when wanting to add a map to an Expo app.

The simplest and the most recommended option is to use react-native-maps. This is the only solution that works with Expo Go, and it's the only one that's documented in the official Expo docs.

However, it's explicitly stated that react-native-maps isn't web-compatible, so if you used it and you also wanted maps on web, your only choice would be to fall back to something like react-google-maps for web. Also, you'd (potentially) have to deal with Apple Maps on iOS vs Google Maps on Android. And – my main reason for steering clear of this option – you'd have to live with the these-days-horrific pricing and draconian ToS of the Google Maps API.

The next option is to use rnmapbox. This is the solution that I instinctively chose first up, and that I stuck with for quite a while, mainly because (for the past several years) I've become accustomed to using Mapbox instead of Google Maps anyway, for maps on old-skool web sites. Plus, rnmapbox claims to (somewhat) support Expo Web.

Unfortunately, "somewhat" is in my opinion an overly optimistic assessment of rnmapbox's web support – basically, instead of trying to go down that route, you should instead fall back to react-map-gl with mapbox-gl-js for web. Plus, I was surprised to learn that Mapbox is no longer the mapping provider of choice for hobbyists, since it decided to stop open-sourcing its mapping library.

Which led me to MapLibre, which is a fork of Mapbox (v1) before the folks at Mapbox decided to release v2 with a non-open-source license. So, with MapLibre (plus MapTiler), I don't have to worry about disagreeable pricing / ToS. And I get basically the same map library on native and web. Although not exactly the same library – it inherits the limitations of the Mapbox libraries, so you need to use maplibre-react-native for native, and fall back to react-map-gl with maplibre-gl-js for web.

Map features

What I needed, and what I'm demo'ing here, is a pretty simple map. It shows the user's location on load (if the user grants location permissions, otherwise it falls back to showing latitude / longitude 0,0 on load). And when the user presses the "Go" button, it grabs the current centre position of the map, and shows the latitude / longitude coordinates of that centre position. That's it!

You're likely to need more functionality than that for a map in your own app. Hopefully this provides you with a humble base to start off from. Good luck getting other bells and whistles working (for native and web)!

Walkthrough

To start off, you'll need an Expo project. If you don't already have one, you can create one with:

npx create-expo-app@latest MyAppThen, you'll need to add both the native and the web mapping libraries as dependencies:

npm install --save @maplibre/maplibre-react-native

npm install --save maplibre-gl

npm install --save react-map-glI like to put everything inside a src/ directory, which is supported but which is not the default for Expo. And I like a structure with various other directories under src/ (see link). My example code from here on assumes that structure. Feel free to suit to your tastes.

You'll need to sign up to MapTiler for an API key. Edit your .env.local file to include this:

EXPO_PUBLIC_MAPTILER_API_KEY=yourmaptilerkeygoeshereDefine this variable in e.g. src/core/config.ts:

export const MAPTILER_API_KEY = process.env.EXPO_PUBLIC_MAPTILER_API_KEY;And define this constant in e.g. src/core/constants.ts:

export const MAPTILER_STYLE_URL =

"https://api.maptiler.com/maps/streets-v2/style.json?key=MAPTILER_API_KEY";The code from here on depends on various utility components, for styling of text and for positioning of elements. I won't go through all those components in this article, I leave it to you to refer to the src/components/ directory.

Before we get into the map code, we need to request location permission, and to get the user's current location (if the user grants permission). I originally had all of this inside the map components, but I then refactored the meat of it out into a utility function, which is very similar to the code in the expo-location docs, and which you can put at e.g. src/core/locationUtils.ts:

import * as Location from "expo-location";

import { Dispatch, SetStateAction } from "react";

export const setCurrentLocationIfAvailable = async (

setLocation: Dispatch<SetStateAction<Location.LocationObjectCoords>>,

setIsLocationUnavailable: Dispatch<SetStateAction<boolean>>,

) => {

let { status } = await Location.requestForegroundPermissionsAsync();

if (status !== "granted") {

setIsLocationUnavailable(true);

return;

}

try {

const currentLocation = await Location.getCurrentPositionAsync({});

setLocation(currentLocation.coords);

} catch (_e) {

setIsLocationUnavailable(true);

}

};Now for the map itself. Let's start by putting the code to render the map for native into a component. This code goes at e.g. src/components/NativeMapView.tsx:

import { StyleSheet } from "react-native";

import * as Location from "expo-location";

import MapLibreGL from "@maplibre/maplibre-react-native";

import { Camera, MapView, MapViewRef } from "@maplibre/maplibre-react-native";

import { Ref, useEffect, useState } from "react";

import { MAPTILER_API_KEY } from "../core/config";

import { MAPTILER_STYLE_URL } from "../core/constants";

import { setCurrentLocationIfAvailable } from "../core/locationUtils";

import { LoadingText } from "./LoadingText";

interface NativeMapViewProps {

mapRef?: Ref<MapViewRef>;

}

export const NativeMapView = (props: NativeMapViewProps) => {

const [location, setLocation] =

useState<Location.LocationObjectCoords | null>(null);

const [isLocationUnavailable, setIsLocationUnavailable] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

MapLibreGL.setAccessToken(null);

setCurrentLocationIfAvailable(setLocation, setIsLocationUnavailable);

}, []);

if (!location && !isLocationUnavailable) {

return <LoadingText />;

}

return (

<MapView

ref={props.mapRef}

style={styles.map}

styleURL={MAPTILER_STYLE_URL.replace(

"MAPTILER_API_KEY",

MAPTILER_API_KEY,

)}

>

<Camera

centerCoordinate={

location ? [location.longitude, location.latitude] : [0, 0]

}

zoomLevel={location ? 12 : 2}

animationDuration={0}

/>

</MapView>

);

};

const styles = StyleSheet.create({

map: {

flex: 1,

},

});This just renders the map, centred and zoomed at the user's current location, without any additional behaviour defined. It's important that we only import from @maplibre/maplibre-react-native in this file, and not in any other files that get loaded for both native and web, because web will freak out if it sees that import.

Next comes the code to render the map for web into a component. This code goes at e.g. src/components/WebMapView.tsx:

import { Ref, useEffect, useState } from "react";

import Map, { MapRef } from "react-map-gl/maplibre";

import * as Location from "expo-location";

import { MAPTILER_API_KEY } from "../core/config";

import { MAPTILER_STYLE_URL } from "../core/constants";

import { setCurrentLocationIfAvailable } from "../core/locationUtils";

import { LoadingText } from "./LoadingText";

interface WebMapViewProps {

mapRef?: Ref<MapRef>;

}

export const WebMapView = (props: WebMapViewProps) => {

const [location, setLocation] =

useState<Location.LocationObjectCoords | null>(null);

const [isLocationUnavailable, setIsLocationUnavailable] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

setCurrentLocationIfAvailable(setLocation, setIsLocationUnavailable);

}, []);

if (!location && !isLocationUnavailable) {

return <LoadingText />;

}

return (

<Map

ref={props.mapRef}

initialViewState={{

latitude: location ? location.latitude : 0,

longitude: location ? location.longitude : 0,

zoom: location ? 12 : 2,

}}

style={{ width: "100%", height: "100%" }}

mapStyle={MAPTILER_STYLE_URL.replace(

"MAPTILER_API_KEY",

MAPTILER_API_KEY,

)}

/>

);

};Once again, this just renders the map, no additional behaviour. And it's important that we only import from react-map-gl/maplibre in this file, because native will freak out if it sees that import.

Now we're going to render the map together with a "Go" button, and we're going to add some additional behaviour, such that when the button is pressed, we grab the current centre coordinates of the map, and then trigger an event using those coordinates. First, the native code for all that, at e.g. src/components/LatLonMap.tsx:

import { useRef } from "react";

import { Button } from "react-native";

import { CenteredContainer } from "./CenteredContainer";

import { FloatingContainer } from "./FloatingContainer";

import { FullWidthContainer } from "./FullWidthContainer";

import { FullWidthAndHeightContainer } from "./FullWidthAndHeightContainer";

import { NativeMapView } from "./NativeMapView";

import { MapViewRef } from "@maplibre/maplibre-react-native";

interface LatLonMapProps {

onPress?: (latitude: number, longitude: number) => Promise<void>;

}

export const LatLonMap = (props: LatLonMapProps) => {

const mapRef = useRef<MapViewRef>(null);

return (

<FullWidthAndHeightContainer>

<NativeMapView mapRef={mapRef} />

<FloatingContainer>

<CenteredContainer>

<FullWidthContainer>

<Button

onPress={async () => {

if (!mapRef.current) {

throw new Error("Missing mapRef");

}

const center = await mapRef.current.getCenter();

if (props.onPress) {

await props.onPress(center[1], center[0]);

}

}}

title="Go"

/>

</FullWidthContainer>

</CenteredContainer>

</FloatingContainer>

</FullWidthAndHeightContainer>

);

};And the web code for all that, at e.g. src/components/LatLonMap.web.tsx:

import { useRef } from "react";

import { Button } from "react-native";

import { CenteredContainer } from "./CenteredContainer";

import { FloatingContainer } from "./FloatingContainer";

import { FullWidthContainer } from "./FullWidthContainer";

import { FullWidthAndHeightContainer } from "./FullWidthAndHeightContainer";

import { WebMapView } from "./WebMapView";

import { MapRef } from "react-map-gl/maplibre";

interface LatLonMapProps {

onPress?: (latitude: number, longitude: number) => Promise<void>;

}

export const LatLonMap = (props: LatLonMapProps) => {

const mapRef = useRef<MapRef>(null);

return (

<FullWidthAndHeightContainer>

<WebMapView mapRef={mapRef} />

<FloatingContainer>

<CenteredContainer>

<FullWidthContainer>

<Button

onPress={async () => {

if (!mapRef.current) {

throw new Error("Missing mapRef");

}

const center = mapRef.current.getCenter();

if (props.onPress) {

await props.onPress(center.lat, center.lng);

}

}}

title="Go"

/>

</FullWidthContainer>

</CenteredContainer>

</FloatingContainer>

</FullWidthAndHeightContainer>

);

};A few key things to note with the above code samples. First of all, we're using Expo's built-in system of platform-specific filename prefixes, to write both a native version (the "default" version ending in .tsx) and a web version (ending in .web.tsx) of the same component. We're importing our NativeMapView component in one version, and our WebMapView component in the other version. The mapRef variable is of a different type, and has a slightly different interface, in each version.

And, finally, we're defining onPress as a prop that gets passed in (and that gets given the coordinates as simple integer parameters when it's called), rather than defining what happens on button press directly in this component, so that we can implement the "on button press" behaviour just once in the calling code (and so that the calling code, rather than this component, gets to decide what happens on button press, thus making this component more reusable).

We're now done writing components. Let's use our new native- and web-compatible map component on our home screen – code goes at e.g. src/app/index.tsx:

import { router } from "expo-router";

import { LatLonMap } from "../components/LatLonMap";

export default function HomeScreen() {

return (

<LatLonMap

onPress={async (latitude: number, longitude: number) => {

router.replace(`/lat-lon?lat=${latitude}&lon=${longitude}`);

}}

/>

);

}The above code is where we implement the "on button press" behaviour. In this case, the behaviour is to redirect to the /lat-lon screen, and to pass the latitude and longitude values as URL parameters.

Lucky last step is to then display the latitude and longitude to the user – code goes at e.g. src/app/(app)/lat-lon.tsx:

import { Button, StyleSheet } from "react-native";

import { useLocalSearchParams } from "expo-router";

import { Link } from "expo-router";

import { ThemedText } from "../../components/ThemedText";

import { ThemedView } from "../../components/ThemedView";

export default function LatLonScreen() {

const { lat, lon } = useLocalSearchParams();

if (typeof lat !== "string") {

throw new Error("lat is not a string");

}

if (typeof lon !== "string") {

throw new Error("lon is not a string");

}

const latVal = parseFloat(lat);

const lonVal = parseFloat(lon);

return (

<ThemedView style={styles.container}>

<ThemedText>Latitude: {latVal}</ThemedText>

<ThemedText>Longitude: {lonVal}</ThemedText>

<Link href="/" asChild>

<Button onPress={() => {}} title="Back" />

</Link>

</ThemedView>

);

}

const styles = StyleSheet.create({

container: {

flex: 1,

alignItems: "center",

justifyContent: "center",

padding: 20,

},

});Map done

There you have it: a map that looks and behaves virtually the same, on both native and web, implemented in a single codebase, with minimal platform-specific code required. I haven't thoroughly looked into how performant, how buggy, or overall how effective this solution is on all platforms, but hey, it's a start. Hope this helps you in your own Expo mapping endeavours.

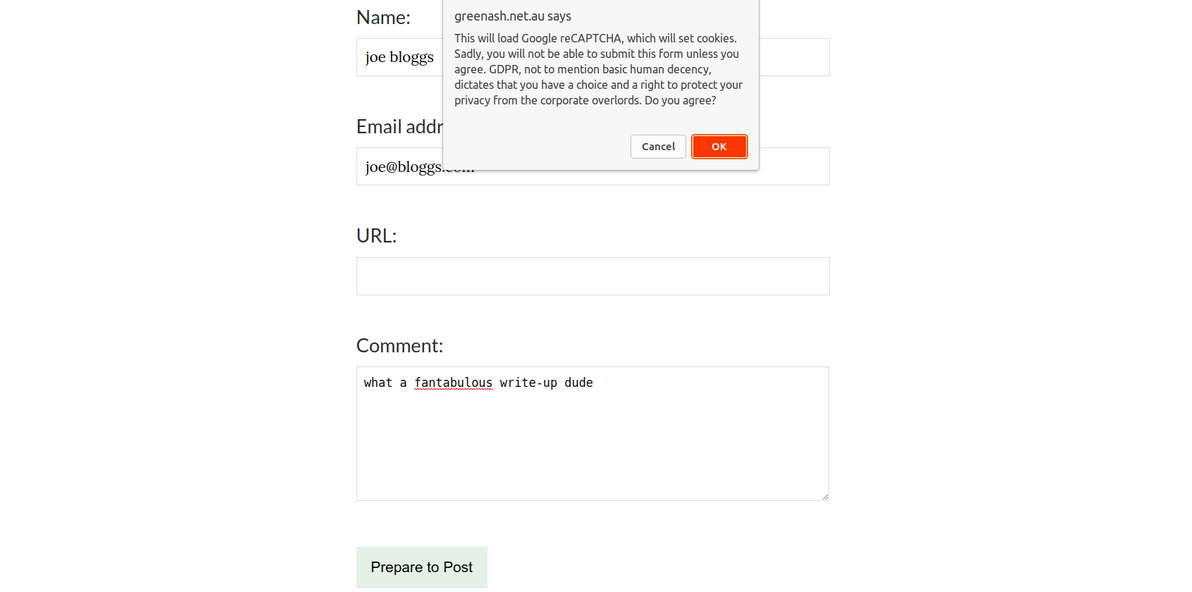

]]>In order to be GDPR-compliant, and in order to just be a good netizen, I made sure, when building GreenAsh v5 earlier this year, to not use services that set cookies at all, wherever possible. In previous iterations of GreenAsh, I used Google Analytics, which (like basically all Google services) is a notorious GDPR offender; this time around, I instead used Cloudflare Web Analytics, which is a good enough replacement for my modest needs, and which ticks all the privacy boxes.

However, on pages with forms at least, I still need Google reCAPTCHA. I'd like to instead use the privacy-conscious hCaptcha, but Netlify Forms only supports reCAPTCHA, so I'm stuck with it for now. Here's how I seek the user's consent before loading reCAPTCHA.

ready(() => {

const submitButton = document.getElementById('submit-after-recaptcha');

if (submitButton == null) {

return;

}

window.originalSubmitFormButtonText = submitButton.textContent;

submitButton.textContent = 'Prepare to ' + window.originalSubmitFormButtonText;

submitButton.addEventListener("click", e => {

if (submitButton.textContent === window.originalSubmitFormButtonText) {

return;

}

const agreeToCookiesMessage =

'This will load Google reCAPTCHA, which will set cookies. Sadly, you will ' +

'not be able to submit this form unless you agree. GDPR, not to mention ' +

'basic human decency, dictates that you have a choice and a right to protect ' +

'your privacy from the corporate overlords. Do you agree?';

if (window.confirm(agreeToCookiesMessage)) {

const recaptchaScript = document.createElement('script');

recaptchaScript.setAttribute(

'src',

'https://www.google.com/recaptcha/api.js?onload=recaptchaOnloadCallback' +

'&render=explicit');

recaptchaScript.setAttribute('async', '');

recaptchaScript.setAttribute('defer', '');

document.head.appendChild(recaptchaScript);

}

e.preventDefault();

});

});I load this JS on every page, thus putting it on the lookout for forms that require reCAPTCHA (in my case, that's comment forms and the contact form). It changes the form's submit button text from, for example, "Send", to instead be "Prepare to Send" (as a hint to the user that clicking the button won't actually submit the form, there will be further action required before that happens).

It hijacks the button's click event, such that if the user hasn't yet provided consent, it shows a prompt. When consent is given, the Google reCAPTCHA JS is added to the DOM, and reCAPTCHA is told to call recaptchaOnloadCallback when it's done loading. If the user has already provided consent, then the button's default click behaviour of triggering form submission is allowed.

{%- if params.recaptchaKey %}

<div id="recaptcha-wrapper"></div>

<script type="text/javascript">

window.recaptchaOnloadCallback = () => {

document.getElementById('submit-after-recaptcha').textContent =

window.originalSubmitFormButtonText;

window.grecaptcha.render(

'recaptcha-wrapper', {'sitekey': '{{ params.recaptchaKey }}'}

);

};

</script>

{%- endif %}I embed this HTML inside every form that requires reCAPTCHA. It defines the wrapper element into which the reCAPTCHA is injected. And it defines recaptchaOnloadCallback, which changes the submit button text back to what it originally was (e.g. changes it from "Prepare to Send" back to "Send"), and which actually renders the reCAPTCHA widget.

<!-- ... -->

<form other-attributes-here data-netlify-recaptcha>

<!-- ... -->

{% include 'components/recaptcha_loader.njk' %}

<p>

<button type="submit" id="submit-after-recaptcha">Send</button>

</p>

</form>

<!-- ... -->This is what my GDPR-compliant, reCAPTCHA-enabled, Netlify-powered contact form looks like. The data-netlify-recaptcha attribute tells Netlify to require a successful reCAPTCHA challenge in order to accept a submission from this form.

That's all there is to it! Not rocket science, but I just thought I'd share this with the world, because despite there being a gazillion posts on the interwebz advising that you "ask for consent before setting cookies", there seem to be surprisingly few step-by-step instructions explaining how to actually do that. And the standard advice appears to be to use a third-party script / plugin that implements an "accept cookies" popup for you, even though it's really easy to implement it yourself.

]]>

Image source: Pinterest

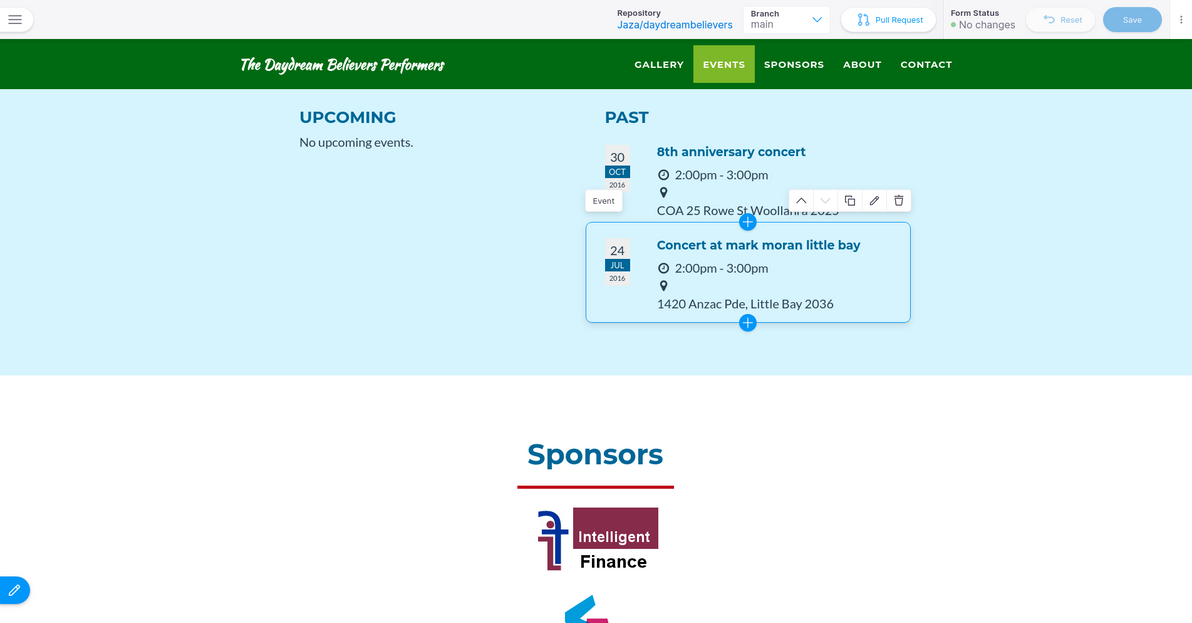

Pressing on with my recent tradition of converting old sites of mine from dynamic to static, this time I converted Daydream Believers. I deliberately chose that site, because its original construction with Flask Editable Site had been an experiment, trying to achieve much the same dynamic inline editing experience as that provided by Tina. Plus, the site has been pretty much abandoned by its owners for quite a long time, so (much like my personal sites) there was basically no risk involved in touching it.

To give you a quick run-down of the history, Flask Editable Site was a noble endeavour of mine, about six years ago – the blurb from the demo sums it up quite well:

The aim of this app is to demonstrate that, with the help of modern JS libraries, and with some well-thought-out server-side snippets, it's now perfectly possible to "bake in" live in-place editing for virtually every content element in a typical brochureware site.

This app is not a CMS. On the contrary, think of it as a proof-of-concept alternative to a CMS. An alternative where there's no "admin area", there's no "editing mode", and there's no "preview button".

There's only direct manipulation.

That sounds eerily similar to "the acronym TinaCMS standing for Tina Is Not A CMS" (yes, yet another recursive acronym in the IT world, in the grand tradition of GNU), as explained in the Tina FAQ:

Tina introduces an entirely new paradigm to the content management space, which can make it difficult to grasp. In short, Tina is a toolkit for making your website its own CMS. It's a suite of packages that enables developers to build a customized content management system into the website itself.

(Who knows, maybe Flask Editable Site was one of the things that inspired the guys behind Tina – if so, I'd be flattered – although I don't believe they've heard of it).

Flask Editable Site boasted essentially the same user experience – i.e. that as soon as you log in, everything is editable inline. But the content got saved the old-skool CMS way, in a relational database. And the page(s) got rendered the old-skool CMS way, dynamically at run-time. And all of that required an old-skool deployment, on an actual server running Nginx / PostgreSQL / gunicorn (or equivalents). Plus, the Flask Editable Site inline components didn't look as good as Tina's do out-of-the-box (although I tried my best, I thought they looked half-decent).

So, I rebuilt Daydream Believers in what is currently the recommended Tina way (it's the way the tinacms.org website itself is currently built): TinaCMS running on top of Next.js, and saving content directly to GitHub via its API. Although I didn't use Tina's GitHub media store (which is currently the easiest way to manage images and other media with Tina), I instead wrote an S3 media store for Tina – something that Tina is sorely lacking, and that many other SSGs / headless CMSes already have. I hope to keep working on that draft PR and to get it merged sometime soon. The current draft works, I'm running it in production, but it has some rough edges.

The biggest hurdle for me, in building my first Tina site, was the fact that a Tina website must be built in React. I've dabbled in React over the past few years, mainly in my full-time job, not particularly by choice. It's rather ironic that this is my first full project built in React, and it's a static website! It's not that I don't like the philosophy or the syntax of React, I'm actually pretty on board with all that (and although I loathe Facebook, I've never held that against React).

It's just that: React is quite a big learning curve; it bloats a web front-end with its gazillion dependencies; and every little thing in the front-end has to be built (or rebuilt) in React, because it doesn't play nicely with any non-React code (e.g. old-skool jQuery) that touches the DOM directly. Anyway, I've now learnt a fair bit of React (still plenty more learning to go); and the finished site seems to load reasonably fast; and I managed to get the JS from the old site playing reasonably nicely with the new site (some via a hacky plonking of old jQuery-based code inside the main React "app" component, and some via rewriting it as actual React code).

TinaCMS isn't really production-ready just yet: I had to fix some issues just to get started with it, including bugs in the official docs and in the beginner guides.

Nevertheless, I'm super impressed with it. This is the kind of delightful user experience that I and many others were trying to build 15+ years ago in Drupal. I've cared about making awesome editable websites for an awfully long time now, and I really am overjoyed to see that awesomeness evolving to a whole new level with Tina.

Compared to the other SSGs that I've used lately – Hugo and Eleventy – Tina (slash Next.js) does have some drawbacks. It's far less mature. It has a slower build time. It doesn't scale as well. The built front-end is fatter. You can't just copy-paste legacy JS into it. You have to accept the complexity cost of React (just to build a static site!). You have to concern yourself with how everything looks in edit mode. Quite a lot of boilerplate code is required for even the simplest site.

You can also accompany traditional SSGs, such as Hugo and Eleventy, with a pretty user-friendly (and free, and SaaS) git-based CMS, such as Forestry (PS: the Forestry guys created Tina) or Netlify CMS. They don't provide any inline editing UI, they just give you a more traditional "admin site". However, they do have pretty good "live preview" functionality. Think of them as a middle ground between a traditional SSG with no editing UI, and Tina with its rich inline editing.

So, would I use Tina again? For a smaller brochureware site, where editing by non-devs needs to be as user-friendly as possible, and where I have the time / money / passion (pick approximately two!) to craft a great experience, sure, I'd love to (once it's matured a bit more). For larger sites (100+ pages), and/or for sites where user-friendly editing isn't that important, I'd probably look elsewhere. Regardless, I'm happy to be on board for the Tina journey ahead.

]]>

First and foremost, Eleventy allows virtually all the custom code you might need. This is in stark contrast to Hugo, with which my biggest gripe was its lack of support for any custom code whatsoever, except for template code. The most basic code hook that Eleventy supports – filters – will get you pretty far: I whipped up some filters for date formatting, for array slicing, for getting parent pages, and for getting subsets of tags. Eleventy's custom collections are also handy: for example, I defined a collection for my nav menu items. I didn't find myself needing to write any Eleventy plugins of my own, but my understanding is that you have access to the same Eleventy API methods in a plugin, as you do in a regular site-level .eleventy.js file.

One of Eleventy's most powerful features is its pagination. It's implemented as a "core plugin" (Pagination.js is the only file in Eleventy core's Plugins directory), but it probably makes sense to just think of it as a core feature, period. Its main use case is, unsurprisingly, for paging a list of content. That is, for generating /articles/, /articles/page/2/, /articles/page/99/, and so on. But it can handle any arbitrary list of data, it doesn't have to be "page content". And it can generate pages based on any permalink pattern, which you can set to not even include a "page number" at all. In this way, Eleventy can generate pages "dynamically" from data! Jaza's World doesn't have a monthly archive, but I could have created one using Eleventy pagination in this way (whereas a dynamically-generated monthly archive is currently impossible in Hugo, so I resorted to just manually defining a page for each month).

Eleventy's pagination still has a few rough edges. In particular, it doesn't (really) currently support "double pagination". That is, /section-foo/parent-bar-generated-by-pagination/child-baz-also-generated-by-pagination/ (although it's the same issue even if parent-bar is generated just by a permalink pattern, without using pagination at that parent level). And I kind of needed that feature, like, badly, for the Gallery section of Jaza's World. So I added support for this to Eleventy myself, by way of letting the pagination key be determined dynamically based on a callback function. As of the time of writing, that PR is still pending review (and so for now, on Jaza's World, I'm running a branch build of Eleventy that contains my change). Hopefully it will get in soon, in which case the enhancement request for double pagination (which is currently one of three "pinned" issues in the Eleventy issue tracker) should be able to be considered fulfilled.

JavaScript isn't my favourite language. I've been avoiding heavy front-end JS coding (with moderate success) for some time, and I've been trying to distance myself from back-end Node.js coding too (with less success). Python has been my language of choice for yonks now. So I'm giving Eleventy a good rap despite it being all JS, not because of it. I like that it's a minimalist JS tool, that it's not tied to any massive framework (such as React), and that it appears to be quite performant (I haven't formally benchmarked it against Hugo, but for my modest needs so far, Eleventy has been on par, it generates Jaza's World with its 500-odd pages in about 2 seconds). And hey, JS is as good a language as any these days, for the kind of script snippets you need when using a static site generator.

Eleventy has come a long way in a short time, but nevertheless, I don't feel that it's worthy yet of being called a really solid tool. Hugo is certainly a more mature piece of software, and a more mature community. In particular, Eleventy feels like a one-man show (Hugo suffers from this too, but it seems to have developed a slightly better contributor base). Kudos to zachleat for all the amazing work he has done and continues to do, but for Eleventy to be sustainable long-term, it needs more of a team.

With Jaza's World, I played around with Eleventy a fair bit, and got a real site built and deployed. But there's more I could do. I didn't bother moving any of my custom code into their own files, nor into separate plugins, I just left them in .eleventy.js. I also didn't bother writing JS unit tests – for a more serious project, what I'd really like to do, is to have tests that run in a CI pipeline (ideally in GitHub Actions), and to only kick off a Netlify deployment once there's a green build (rather than the usual setup of Netlify deploying as soon as the master branch in GitHub is updated).

Site building in Eleventy has been fun, I reckon I'll be doing more of it!

]]>I decided (and I was encouraged by stakeholders) to build the tool as a single-page application, i.e. as a web app where almost all of the front-end is powered by JavaScript, and where the page is redrawn via AJAX calls and client-side templates. This was my first experience developing such an app; as such, I'd like to reflect on the choices I made, and on my understanding of the technology as it stands now.

Drowning in frameworks

Image source: Memory Alpha (originally from Star Trek TOS Season 2 Ep 13).

Building single-page applications is all the rage these days; as such, a gazillion frameworks have popped up, all promising to take the pain out of the dev work for you. In reality, when your problem is that you need to create an app, and you think: "I know, I'll go and choose a JS framework", now you have two problems.

Actually, that's not the full story either. When you choose the wrong JS* framework – due to it being unsuitable for your project, and/or due to your failing to grok it – and you have to look for a framework a second time, and port the code you've already started writing… now you've got three problems!

(* I'd prefer to just refer to these frameworks as "JS", rather than use the much-bandied-about term "MVC", because not all such frameworks are MVC, and because one's project may be unsuitable for client-side MVC anyway).

Ah, the joy of first-time blunders.

I started by choosing Ember.js. It's one of the most popular frameworks at the moment. It does everything you could possibly need for your funky new JS app. Turns out that: (a) Ember was complete overkill for my relatively simple app; and (b) despite my best efforts, I failed to grok Ember, and I felt that my time would be better spent switching to something else and thereafter working more efficiently, than continuing to grapple with Ember's philosophy and complexity.

In the end, I settled on Sammy.js. This is one of the lesser-known frameworks out there. It boasts far less features than Ember.js (and even so, I haven't used all that Sammy.js offers either). It doesn't get in the way of my app's functionality. Many of its features are just a thin wrapper on top of jQuery, which I already know intimately. It adds a few bits 'n' pieces into my existing JS ecosystem, to give my app more structure and more interactivity; rather than nuking my existing ecosystem, and making me feel like single-page JS is a whole new language.

My advice to others who are choosing a whiz-bang JS framework for the first time: don't necessarily go with the most popular or the most full-featured framework you find (although don't discard such options either); think long and hard about what your app will actually do (more on that below), and choose an appropriate framework for your use-case; and make liberal use of online resources such as reviews (I also found TodoMVC extremely useful, plus I used its well-written code samples as the foundation for my own code).

What seems to be the problem?

Image source: Funny Junk (originally from South Park).

Ok, so you're going to write a single-page JS app. What will your app actually do? "Single-page JS app" can mean anything; and if we're trying to find the appropriate tool for the job, then the job itself needs to be clearly defined. So, let's break it down a bit.

Is the app (mainly) read-write, or is it read-only? This is a critical question, possibly more so than anything else. One of the biggest challenges with rich JS apps, is synchronising data between client and server. If data is only flowing one day (downstream), that's a whole lot less complexity than if data is flowing upstream as well.

Turns out that JS frameworks, in general, have dedicated a lot of their feature set to supporting read-write apps. They usually do this by having "models" (the "M" in "MVC"), which are the "source of truth" on the client-side; and by "binding" these models to elements in the DOM. When the value of a DOM element changes, that triggers a model data change, which in turn (often) triggers a server-side data update. Conversely, when new data arrives from the server, the model data is updated accordingly, and that update then propagates automatically to a value in the DOM.

Even the quintessential "Todo app" example has two-way data. Turns out, however, that my app only has one-way data. My app is all about sending queries to the server (with some simple filters), and receiving metric data in response. What's more, the received data is aggregate data (ready to be rendered as charts and tables), not individual entities that can easily be stored in a model. So, turns out that my life is easier without worrying about models or event bindings at all. Receive JSON, pipe it to the chart renderer (NVD3 for most charts), end of story.

Can displayed data change dynamically within a single JS route, or can it only change when the route changes? Once again, the former entails a lot more complexity than the latter. In my app's case, each JS route (handled by Sammy.js, same as with other frameworks, as "the part of the URL after the hash character") is a single report (containing one or more graphs and tables). The report elements themselves aren't dynamic (except that hovering over various graph elements shows more info). Changing the filters of the current report, or going to a different report, involves executing a new JS route.

So, if data isn't changing dynamically within a single JS route, why bother with complex event bindings? Some simple "old-skool" jQuery event handlers may be all that's necessary.

In summary, in the case of my app, all that it really needed in a JS framework was: client-side routing (which Sammy.js provides using nice, simple callbacks); local storage (Sammy.js has a thin wrapper on top of the HTML5 local storage API); AJAX communication (Sammy.js has a thin wrapper on top of jQuery for this); and templating (out-of-the-box Sammy.js supports John Resig's JS micro-templating system). And that's already a whole lot of funky new client-side components to learn and use. Why complicate things further?

Early days

Image source: Stormy Horizon Picture.

All in all, I enjoyed building my first single-page JS app, and I'm reasonably happy with how it turned out to be architected. The front-end uses Sammy.js, D3.js/NVD3, and Bootstrap. The back-end uses Flask (Python) and MongoDB. Other than the login page and the admin pages, the app only has one non-JSON server-side route (the home page), and the rest is handled with client-side routes. The client-side is fairly simple, compared to many rich JS apps being built today; but then again, every app is unique.

I think that right now, we're still in Wild West times as far as building single-page apps goes. In particular, there are way too many frameworks in abundance; as the space matures, no doubt most of these frameworks will die off, and only a handful will thrive in the long-term. There's also a shortage of good advice about design patterns for single-page apps so far, although Mixu's book is a great foundation resource.

Single-page JS technology has plenty of advantages: it can lead to a more responsive, more beautiful app; and, when done right, its JS component can be architected just as cleanly and correctly as everything would be (traditionally) architected on the server-side. Remember, though, that it's just one piece in the puzzle, and that it only needs to be as complex as the app you're building.

]]>