To be fair to those folks, it's true that – as they claim – the water level of various landmarks around the world, such as the Statue of Liberty, Plymouth Rock, and (in my own stomping ground of Sydney Harbour) Fort Denison, has not "visibly" risen since they were erected.

The fact, per the consensus of reputable scientists, is that the global average sea level has risen by 15-25cm (6-10") since 1900. Now, I'm willing to entertain the notion that, alright, for all practical purposes, that's not much. And that's just the average. So I consider it not unreasonable to concede that there are numerous places in the world today, where the sea level has barely, if at all, risen.

But.

Image source: PxHere.

The thing is, sea level rise lags behind global warming by several decades. So (if you'll excuse my hitting-rather-close-to-home choice of pun), what we've seen so far is just the tip of the iceberg. We've already locked in another 10-25cm (4-10") of sea level rise between now and 2050. And we're currently looking at a minimum 28-61cm (11-24") of sea level rise between now and 2100, and a minimum 40-95cm (16-38") of sea level rise between now and 2200. And those are the best-case scenarios, based: on the most conservative of scientists' conclusions; and on the world taking drastic action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions starting right now (a depressingly unlikely occurrence).

So, ok, perhaps sea level rise ain't gotten real yet for most people (although it sure has for some people). But I got news for y'all: it's gonna get a whole lot realer.

It's complicated

Sea level rise is, admittedly, one of the tricker symptoms of climate change to get your head around.

Firstly, it hasn't occurred – at least, not in most of the world – in as dramatic or as visible a manner as various other phenomena have. Glacial melting is clear as day, to anyone who is a local resident of, or a long-time vacationer to, one of the hotspots. Droughts, heatwaves and bushfires / wildfires have been noticeably increasing in both frequency and intensity, in North America, in Europe, and here in Australia (to name but a few places). Glaciers don't un-retreat, and charred countryside doesn't un-burn, when the tide goes out.

The only places in the world where the sea level rise merde (if you'll excuse my French) has already visibly hit the fan, are remote, impoverished, sparsely-populated, seldom-visited islands, particularly in the Pacific. So it's relatively easy, right now, for much of the world to feign blissful ignorance, if everything appears to still be cool and normal on the coastline down the road from your house.

Image source: PxHere.

Also, the amount of sea level rise that has occurred over the past century-and-a-bit is, historically speaking, quite modest. Sure, it's the most significant rise in the past 3,000 years. However, from around 20,000 years ago (at the end of the last ice age), until around the start of Classical Antiquity, the sea level rose by about 125m (400'). That's great ammunition for deniers to go around claiming: "sea levels have always risen and fallen naturally, whatever is happening now has nothing to do with human activity".

Secondly, although scientists unanimously agree that sea level rise is accelerating and that it will get pretty bad pretty soon, there is massive uncertainty as to exactly how much and when. As I said, a 28-61cm (11-24") sea level rise between now and 2100 is the best-case forecast. The current worst-case forecast is a 1.3-1.6m (4-5') sea level rise between now and 2100. There are numerous forecasts in between.

Apart from not realising that it's already happening, and not realising that it lags behind air temperature changes by several decades, most people also don't realise for just how insanely long the sea level is going to keep on rising, as a result of industrialised humanity's love affair with carbon. In this arena too, estimates vary quite widely. But we're looking at a best-case forecast of a 2-3m (6-10') sea level rise over the next 2,000 years, and a current worse-case forecast of a 19-22m (62-72') sea level rise over the next 2,000 years.

But that's not all. The thing is, all that carbon we've emitted lately, it just ain't going anywhere in a hurry, it's going to keep hanging around like a bad smell. As such, we're looking a a best-case forecast of a 6-7m (19-23') sea level rise over the next 10,000 years, and a current worst-case forecast of a 52m (170') sea level rise over the next 10,000 years.

Image source: Wallpaper Delight.

Get ready

The sea may have only barely perceptibly risen so far, but it's about to rise a whole lot more. It's going to happen soon enough, that it will have a real and devastating effect, not on your great-grandchildren, not on your grandchildren, but on your children (and mine) who have already been born. Even considering the best-case forecasts, the map of the world's coastlines will already be different by the end of this century; and it will be unrecognisable in millennia to come.

]]>

Image source: Legends Revealed

Amazingly, to this day – more than three decades after the fall of communism – this city of about 100,000 residents (and its surrounds, including the Mayak nuclear facility, which is ground zero) remains a "closed city", with entry forbidden to all non-authorised personnel.

And, apart from being enclosed by barbed wire, it appears to also be enclosed in a time bubble, with the locals still routinely parroting the Soviet propaganda that labelled them "the nuclear shield and saviours of the world"; and with the Soviet-era pact still effectively in place that, in exchange for their loyalty, their silence, and a not-un-unhealthy dose of radiation, their basic needs (and some relative luxuries to boot) are taken care of for life.

Image source: Google Maps

So, as I said, there's very little information available on Ozersk, because to this day: it remains forbidden for virtually anyone to enter the area; it remains forbidden for anyone involved to divulge any information; and it remains forbidden to take photos / videos of it, or to access any documents relating to it. For over three decades, it had no name and was marked on no maps; and honestly, it seems like that might as well still be the case.

Image source: imgflip

Frankly, even had the 1957 explosion not occurred, the area would still be horrendously contaminated. Both before and after that incident, they were dumping enormous quantities of unadulterated radioactive waste directly into the water bodies in the vicinity, and indeed, they continue to do so, to this day. It's astounding that anyone still lives there – especially since, ostensibly, you know, Russians are able to live where they choose these days.

Image source: imgflip

As far as I can gather, from the available sources, most of the present-day residents of Ozersk are the descendants of those who were originally forced to go and live there in Stalin's time. And, apparently, most people who have been born and raised there since the fall of the USSR, choose to stay, due to: family ties; the government continuing to provide for their wellbeing; ongoing patriotic pride in fulfilling their duty; fear of the big bad world outside; and a belief (foolhardy or not) that the health risks are manageable. It's certainly possible that there are more sinister reasons why most people stay; but then again, in my opinion, it's not implausible that no outright threats or prohibitions are needed, in order to maintain the status quo.

Image source: Wonkapedia

Only one insider appears to have denounced the whole spectacle in recent history: lifelong resident Nadezhda Kutepova, who gave an in-depth interview with Western media several years ago. Kutepova fled Ozersk, and Russia, after threats were made against her, due to her campaigning to expose the truth about the prevalence of radiation sickness in her home town.

And only one outsider appears to have ever gotten in covertly, lived, and told the tale: Samira Goetschel, who produced City 40, the world's only documentary about life in Ozersk (the film features interview footage with Kutepova, along with several other Ozersk locals). Honestly, life inside North Korea has been covered more comprehensively than this.

Image source: imgflip

Considering how things are going in Putin's Russia, I don't imagine anything will be changing in Ozersk for a long time yet. Looks like business as usual – utterly trash the environment, manufacture dodgy nuclear stuff, maintain total secrecy, brainwash the locals, cause sickness and death – is set to continue indefinitely.

You can find much more in-depth information, in many of the articles and videos that I've linked to. Anyway, in a nutshell, Ozersk: you've never been there, and you'll never be able to go there, even if you wanted to. Which you don't. Now, please forget everything you've just read. This article will self-destruct in five seconds.

]]>Nobody (except Indonesia!) is disputing that an awful lot of bad stuff has happened in Indonesian Papua over the last half-century or so, and that the vast majority of the blood is on the Indonesian government's hands. However, is it true that the Australian government is not only silent on, but also complicit in, said bad stuff?

Image source: YouTube

Note: in keeping with what appears to be the standard in English-language media, for the rest of this article I'll be referring to the whole western half of the island of New Guinea – that is, to both of the present-day Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua – collectively as "West Papua".

Grasberg mine

Let's start with one of the video's least controversial claims – one that's about a simple objective fact, and one that has nothing to do with Australia:

[Grasberg mine] … the biggest copper and gold mine in the world

Close enough

I had never heard of the Grasberg mine before. Just like I had never heard much in general about West Papua before – even though it's only about 200km from (the near-uninhabited northern tip of) Australia. Which I guess is due to the scant media coverage afforded to what has become a forgotten region.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Anyway, Grasberg is indeed big (it's the biggest mine in Indonesia), it's massively polluting, and it's extremely lucrative (both for US-based Freeport-McMoRan and for the Indonesian government).

Image source: The Guardian

Grasberg is actually the second-biggest gold mine in the world, based on total reserves, but it's a close second. And it's the fifth-biggest gold mine in the world, based on production. It's the tenth-biggest copper mine in the world. And Freeport-McMoRan is the third-biggest copper mining company in the world. Exact rankings vary by source and by year, but Grasberg ranks near the top consistently.

I declare this claim to be very close to the truth.

Accessory to abuses

we've [Australia] done everything we can to help our mates [Indonesian National Military] beat the living Fak-Fak out of those indigenous folks

Exaggerated

Woah, woah, woah! Whaaa…?

Yes, Australia has supplied the Indonesian military and the Indonesian police with training and equipment over many years. And yes, some of those trained personnel have gone on to commit human rights abuses in West Papua. And yes, there are calls for Australia to cease all support for the Indonesian military.

Image source: International Academics for West Papua

But. Are a significant number of Australian-trained Indonesian government personnel deployed in West Papua, compared with elsewhere in the vastness of Indonesia? We don't know (although it seems unlikely). Does Australia train Indonesian personnel in a manner that encourages violence towards civilians? No idea (but I should hope not). And does Australia have any control over what the Indonesian government does with the resources provided to it? Not really.

I agree that, considering the Indonesian military's track record of human rights abuses, it would probably be a good idea for Australia to stop resourcing it. The risk of Australia indirectly facilitating human rights abuses, in my opinion, outweighs the diplomatic and geopolitical benefits of neighbourly cooperation.

Nevertheless: Australia (as far as we know) has no boots on the ground in West Papua; (I have to reluctantly say that) Australia is not responsible for how the Indonesian military utilises the training and equipment that it has received; and there's insufficient evidence to link Australia's support of the Indonesian military to date, with goings-on in West Papua.

I declare this claim to be exaggerated.

Corporate plunder

so that our other mates [Rio Tinto, LG, BP, Freeport-McMoRan] can come in and start makin' the ching ching

Close enough

At the time that the video was made (2018), Rio Tinto owned a significant stake in the Grasberg mine, and it most certainly was "makin' the ching ching" from that stake. Although shortly after that, Rio Tinto sold all of its right to 40% of the mine's production, and is now completely divested of its interest in the enterprise. Rio Tinto is a British-Australian company, and is most definitely one of the Australian government's mates.

Freeport-McMoRan has, of course, been Grasberg's principal owner and operator for most of the mine's history, as well as the principal entity that has been raking in on the mine's insane profits. The company has some business ventures in Australia, although its ties with the Australian economy, and therefore with the Australian government, appear to be quite modest.

BP is the main owner of the Tangguh gas field, which is probably the second-largest and second-most-lucrative (and second-most-polluting!) industrial enterprise in West Papua. BP is of course a British company, but it has a significant presence in Australia. LG appears to also be involved in Tangguh. LG is a Korean company, and it has modest ties to the Australian economy.

Image source: KBR

So, all of these companies could be considered "mates" of the Australian government (some more so than others). And all of them are, or until recently were, "makin' the ching ching" in West Papua.

I declare this claim to be very close to the truth.

Stopping independence

Remember when two Papuans [Clemens Runaweri and Willem Zonggonau] tried to flee to the UN to expose this bulls***? We [Australia] prevented them from ever getting there, by detaining them on Manus Island

Checks out

Well, no, I don't remember it, because – apart from the fact that it happened long before I was born – it's an incident that has scarcely ever been covered by the media (much like the lack of media coverage of West Papua in general). Nevertheless, it did happen, and it is documented:

In May 1969, two young West Papuan leaders named Clemens Runaweri and Willem Zonggonau attempted to board a plane in Port Moresby for New York so that they could sound the alarm at UN headquarters. At the request of the Indonesian government, Australian authorities detained them on Manus Island when their plane stopped to refuel, ensuring that West Papuan voices were silenced.

Source: ABC Radio National

After being briefly detained, the two men lived the rest of their lives in exile in Papua New Guinea. Zonggonau died in Sydney in 2006, where he and Runaweri were visiting, still campaigning to free their homeland until the end. Runaweri died in Port Moresby in 2011.

Interestingly, it also turns out that the detaining of these men, along with several hundred other West Papuans, in the late 1960s, was the little-known beginning of Australia's now-infamous use of Manus Island as a place to let refugees rot indefinitely.

Image source: The New York Times

I declare this claim to be 100% correct.

Training hitmen

We [Australia] helped train [at the Indonesia-Australia Defence Alumni Association (IKAHAN)] and arm those heroes [the hitmen who assassinated the Papuans' leader Theys Eluay in 2001]

Exaggerated

Theys Eluay was indeed the chairman of the Papua Presidium Council – he was even described as "Papua's would-be first president" – and his death in 2001 was indeed widely attributed to the Indonesian military.

There's no conclusive evidence that the soldiers who were found guilty of Eluay's murder (who were part of Kopassus, the Indonesian special forces), received any training from Australia. However, Australia has provided training to Kopassus over many years, including during the 1980s and 1990s. This co-operation has continued into more recent times, during which claims have been made that Kopassus is responsible for ongoing human rights abuses in Papua.

Image source: ABC

I don't know why IKAHAN was mentioned together with the 2001 murder of Eluay, because it wasn't founded until 2011, so one couldn't possibly have anything to do with the other. It's possible that Eluay's killers received Australian-backed training elsewhere, but not there. Similarly, it's possible that training undertaken at IKAHAN has contributed to other shameful incidents in West Papua, but not that one. Mentioning IKAHAN does nothing except conflate the facts.

In any case, I repeat, (I have to reluctantly say that) Australia is not responsible for how the Indonesian military utilises the training and equipment that it has received; and there's insufficient evidence to link Australia's support of the Indonesian military to date, with goings-on in West Papua.

I declare this claim to be exaggerated.

Shipments from Cairns

which [Grasberg mine] is serviced by massive shipments from Cairns. Cairns! The Aussie town supplying West Papua's Death Star with all its operational needs

"Citations needed"

This claim really came at me out of left field. So much so, that it was the main impetus for me penning this article as a fact check. Can it be true? Is the laid-back tourist town of Cairns really the source of regular shipments of supplies, to the industrial hellhole that is Grasberg?

Image source: Bulk Handling Review

I honestly don't know how TJM got their hands on this bit of intel, because there's barely any mention of it in any media, mainstream or otherwise. Clearly, this was an arrangement that all involved parties made a concerted effort to keep under the radar for many years.

In any case, yes, it appears to be true. Or, at least, it was true at the time that the video was published, and it had been true for about 45 years, up until that time. Then, in 2019, the shipping, and Freeport-McMoRan's presence in town, apparently disappeared from Cairns, presumably replaced by alternative logistics based in Indonesia (and presumably due to the Indonesian government having negotiated to make itself the majority owner of Grasberg shortly before that).

It makes sense logistically. Cairns is one of the closest fully-equipped ports to Grasberg, only slightly further away than Darwin. Much closer than Jakarta or any of the other big ports in the Indonesian heartland. And I can imagine that, for various economic and political reasons, it may well have been easier to supply Grasberg primarily from Australia rather than from elsewhere within Indonesia.

I would consider that this claim fully checks out, if I could find more sources to corroborate it. However, there's virtually no word of it in any mainstream media; and the sources that do mention it are old and of uncertain reliability.

I declare this claim to be "citations needed".

Verdict

Australia is proud to continue its fine tradition of complicity in West Papua

Exaggerated

In conclusion, I declare that the video "Honest Government Ad: Visit West Papua", on the whole, checks out. In particular, its allegation of the Australian government being economically complicit in the large-scale corporate plunder and environmental devastation of West Papua – by way of it having significant ties with many of the multinational companies operating there – is spot-on.

But. Regarding the Australian government being militarily complicit in human rights abuses in West Papua, I consider that to be a stronger allegation than is warranted. Providing training and equipment to the Indonesian military, and then turning a blind eye to the Indonesian military's actions, is deplorable, to be sure. Australia being apathetic towards human rights abuses, would be a valid allegation.

To be "complicit", in my opinion, there would have to be Australian personnel on the ground, actively committing abuses alongside Indonesian personnel, or actively aiding and abetting such abuses.

Don't get me wrong, I most certainly am not defending Australia as the patron saint of West Papua, and I'm not absolving Australia of any and all responsibility towards human rights abuses in West Papua. I'm just saying that TJM got a bit carried away with the level of blame they apportioned to Australia on that front.

Image source: new mandala

Also, bear in mind that the only reason I'm "going soft" on Australia here, is due to a lack of evidence of Australia's direct involvement militarily in West Papua. It's quite possible that there is indeed a more direct involvement, but that all evidence of it has been suppressed, both by Indonesia and by Australia.

And hey, I'm trying to play devil's advocate in this here article, which means that I'm giving TJM more of a grilling than I otherwise would, were I to simply preach my unadulterated opinion.

I'd like to wholeheartedly thank TJM for producing this video (along with all their other videos). Despite me giving them a hard time here, the video is – as TJM themselves tongue-in-cheek say – "surprisingly honest!". It educated me immensely, and I hope it educates many more folks just as immensely, as to the lamentable goings-on, right on Australia's doorstep, about which we Aussies (not to mention the rest of the world) hear unacceptably little.

The Australian government is, at the very least, one of those responsible for maintaining the status quo in West Papua. And "business as usual" over there clearly includes a generous dollop of atrocities.

]]>

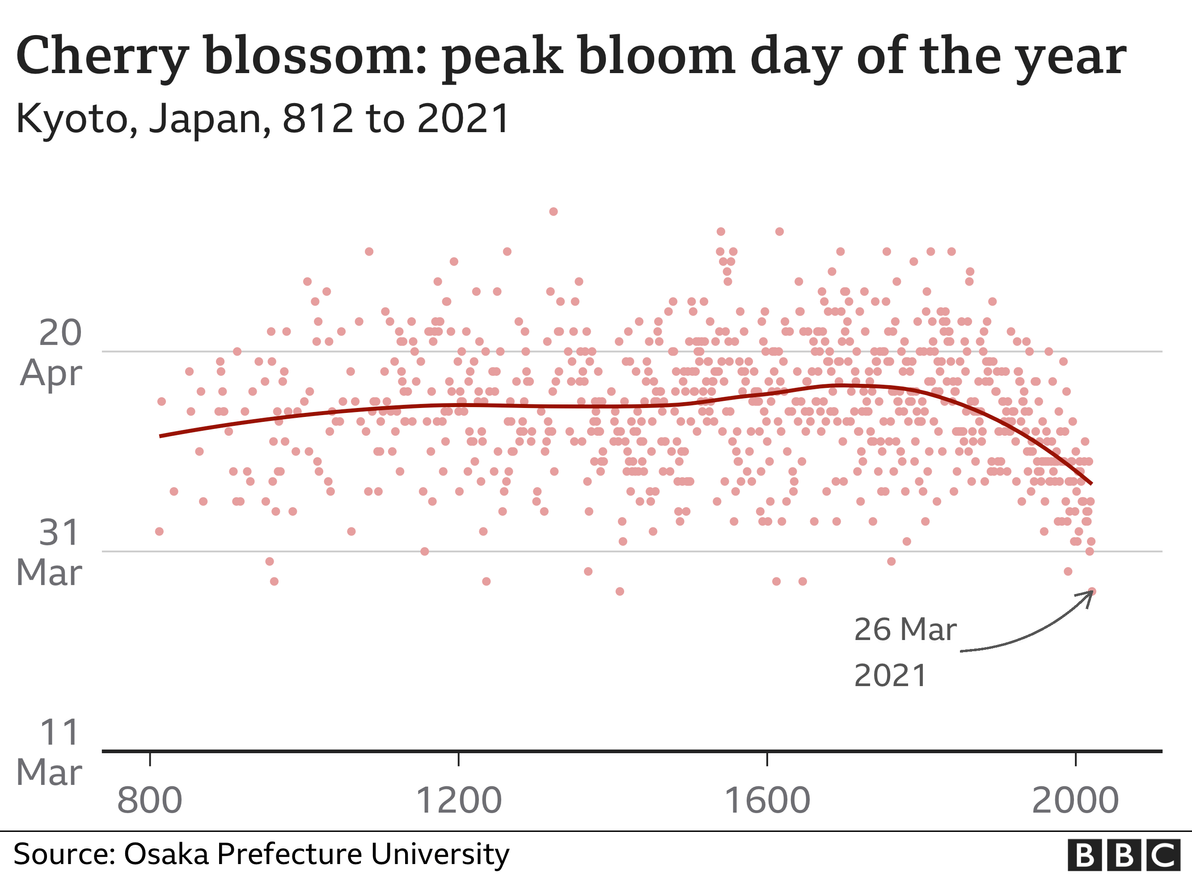

Image source: BBC News

I just want to briefly dive in to the data set (and the academic research behind it), and to explain why, in my opinion, it's such a gem in the sea of modern-day climate science.

Can we trust this data?

Green-minded lefties (of whom I count myself one) would tend to trust this data, without feeling the need to dig any deeper into where it came from, nor into how it got collated. However, putting myself in the shoes of a climate change sceptic, I can imagine that there are plenty of people out there who'd demand the full story, before being willing to digest the data, let alone to accept any conclusions arising from it. And hey, regardless of your political or other leanings, it's a good idea for everyone to conduct some due diligence background research, and to not blindly be believin' (especially not anything that you read online, because I hate to break it to you, but not everything on the internet is true!).

Image source: me.me

When I first saw the above graph – of the cherry blossom dates over 1,200 years – in the mainstream media, I assumed that the data points all came from a nice, single, clean, consistent source. Like, you know, a single giant tome, a "cherry blossom codex", that one wizened dude in each generation has been adding a line to, once a year, every year since 812 CE, noting down the date. But even the Japanese aren't quite that meticulous. The real world is messy!

According to the introductory text on the page from Osaka Prefecture University, the pre-modern data points – defined as being from 812 CE to 1880 – were collected:

… from many diaries and chronicles written by Emperors, aristocrats, goveners and monks at Kyoto …

For every data point, the source is listed. Many of the sources yield little or no results in a Google search. For example, try searching (including quotes) for "Yoshidake Hinamiki" (the source for the data points from 1402 and 1403), for which the only results are a handful of academic papers and books in which it's cited, and nothing actually explaining what it is, nor showing more than a few lines of the original text.

Or try searching for "Inryogen Nichiroku" (the source for various data points between 1438 and 1490), which has even fewer results: just the cherry blossom data in question, nothing else! I'm assuming that information about these sources is so limited, mainly due to there being virtually no English-language resources about them, and/or due to the actual titles of the sources having no standard for correct English transliteration. I'm afraid that, since my knowledge of Japanese is close to zilch, I'm unable to search for anything much online in Japanese, let alone for information about esoteric centuries-old texts.

The listed source for the very first data point of 812 CE is the Nihon Kōki. That book, along with the other five books that comprise the Rikkokushi – and all of which are compiled in the Ruijū Kokushi – appears to be one of the more famous sources. It was officially commissioned by the Emperor, and was authored by several statesmen of the imperial court. It appears to be generally considered as a reliable source of information about life in 8th and 9th century Japan.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

The data points from 812 CE to 1400 are somewhat sporadic. There are numerous gaps, sometimes of as much as 20 years. Nevertheless, considering the large time scale under study, the data for that period is (in my unqualified layman's opinion) of high enough frequency for it to be statistically useful. The data points from 1400 onwards are more contiguous (i.e. there are far fewer gaps), so there appears to have been a fairly consistent and systematic record-keeping regime in place since then.

How much you want to trust the pre-modern data really depends, I guess, on what your opinion of Japanese civilisation is. When considering that matter, bear in mind that the Imperial House of Japan is believed to be the oldest continuous monarchy in the world, and that going back as far as the 8th century, Japan was already notable for its written works. Personally, I'd be willing to give millenium-old Japanese texts the benefit of the doubt in terms of their accuracy, more than I'd be willing to do so for texts from most other parts of the world from that era.

The man behind this data set, Yasuyuki Aono, is an Associate Professor in Environmental Sciences and Technology at Osaka Prefecture University (not a world-class university, but apparently it's roughly one of the top 20 universities in Japan). He has published numerous articles over his 30+ year career. His 2008 paper: Phenological data series of cherry tree flowering in Kyoto, Japan, and its application to reconstruction of springtime temperatures since the 9th century – the paper which is the primary source of much of the data set – is his seminal work, having been cited over 250 times to date.

So, the data set, the historical sources, and the academic credentials, all have some warts. But, in my opinion, those warts really are on the small side. It seems to me like pretty solid research. And it appears to have all been quite thoroughly peer reviewed, over numerous publications, in numerous different journals, by numerous authors, over many years. You can and should draw your own conclusions, but personally, I declare this data to be trustworthy, and I assert that anyone who doubts its trustworthiness (after conducting an equivalent level of background research to mine) is splitting hairs.

It don't get much simpler

Having got that due diligence out of the way, I hope that even any climate change sceptics out there who happen to have read this far (assuming that any such folk should ever care to read an article like this on a web site like mine) are willing to admit: this cherry blossom data is telling us something!

I was originally hoping to give this article a title that went something like: "Five indisputable bits of climate change evidence". That is, I was hoping to find four or so other bits of evidence as good as this one. But I couldn't! As far as I can tell, there's no other record of any other natural phenomenon on this Earth (climate change related or otherwise), that has been consistently recorded, in writing, more-or-less annually, for the past 1,000+ years. So I had to scrap that title, and just focus on the cherry blossoms.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Apart from the sheer length of the time span, the other thing that makes this such a gem, is the fact that the data in question is so simple. It's just the date of when people saw their favourite flower bloom each year! It's pretty hard to record it wrongly – even a thousand years ago, I think people knew what day of the year it was. It's not like temperature, or any other non-discrete value, that has to be carefully measured, by trained experts, using sensitive calibrated instruments. Any old doofus can write today's date, and get it right. It's not rocket science!

That's why I really am excited about this cherry blossom data being the most indisputable evidence of climate change ever. It's not going back 200 years, it's going back 1,200 years. It's not projected data, it's actual data. It's not measured, it's observed. And it was pretty steady for a whole millenium, before taking a noticeable nosedive in the 20th century. If this doesn't convince you that man-made climate change is real, then you, my friend, have well and truly buried your head in the sand.

]]>

Image source: Favourite picture: Road construction in Siberia – RoadStars.

Naturally, such places also happen to be largely bereft of any other human infrastructure, such as buildings; and to be largely bereft of any human population. These are places where, in general, nothing at all is to be encountered save for sand, ice, and rock. However, that's just coincidental. My only criteria, for the purpose of this article, is a lack of roads.

Alaska

I was inspired to write this article after reading James Michener's epic novel Alaska. Before reading that book, I had only a vague knowledge of most things about Alaska, including just how big, how empty, and how inaccessible it is.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

One might think that, on account of it being part of the United States, Alaska boasts a reasonably comprehensive road network. Think again. Unlike the "Lower 48" (as the contiguous USA is referred to up there), only a small part of Alaska has roads of any sort at all, and that's the south-east corner around Anchorage and Fairbanks. And even there, the main routes are really part of the American Interstate network only on paper.

As you can see from the map, the entire western part of the state, and most of the north of the state, lack any road routes whatsoever. The north-east is also almost without roads, except for the Dalton Highway – better known locally as "The Haul Road" – which is a crude and uninhabited route for most of its length.

There has been discussion for decades about the possibility of building a road to Nome, which is the biggest settlement in western Alaska. However, such a road remains a pipe dream. It's also impossible to drive to Barrow, which is the biggest place in northern Alaska, and also the northernmost city in North America. This is despite Barrow being only about 300km west of the Dalton Highway's terminus at the Prudhoe Bay oilfields.

Road building is a trouble-fraught enterprise in Alaska, where distances are vast, population centres are few (or none), and geography / climate is harsh. In particular, building roads on permafrost (of which much of Alaska's terrain is) can be challenging, because the frozen soil expands in summer, and violently cracks whatever is on top of it. Also, while solid in winter, permafrost turns to muddy swamps in summer.

Image source: Yukon Animator.

It's no wonder, then, that for most of the far-flung outposts in northern and western Alaska, the main forms of transport are by sea or air. Where terrestrial transport is taken, it's most commonly in the form of a dog sled, and remains so to this day. In winter, Alaska's true main highways are its frozen rivers – particularly the mighty Yukon – which have been traversed by sled dogs, on foot (often with fatal results), and even by bicycle.

Canada

Much like its neighbour Alaska, northern Canada is also a vast expanse of frozen tundra that remains largely uninhabited. Considering the enormity of the area in question, Canada has actually made quite impressive progress in the building of roads further north. However, as the map illustrates, much of the north remains pristine and unblemished.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The biggest chunk of the roadless Canadian north is the territory of Nunavut. There are no roads to Nunavut (unless you count this), nor are there any linking its far-flung towns. As its Wikipedia page states, Nunavut is "the newest, largest, northernmost, and least populous territory of Canada". Nunavut's principal settlements of Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet, and Cambridge Bay can only be reached by sea or air.

Image source: Huffington Post.

The Northwest Territories is barren in many places, too. The entire eastern pocket of the Territories, bordering Nunavut and Saskatchewan (i.e. everything east of Tibbitt Lake, where the Ingraham Trail ends), has not a single road. And there are no roads north of Wrigley (where the Mackenzie Highway ends), except for the northernmost section of the Dempster Highway up to Inuvik. There are also no roads north of the Dempster Highway in Yukon Territory. And, on the other side of Canada, there are no roads in Quebec or Labrador north of Caniapiscau and the Trans-Taiga Road.

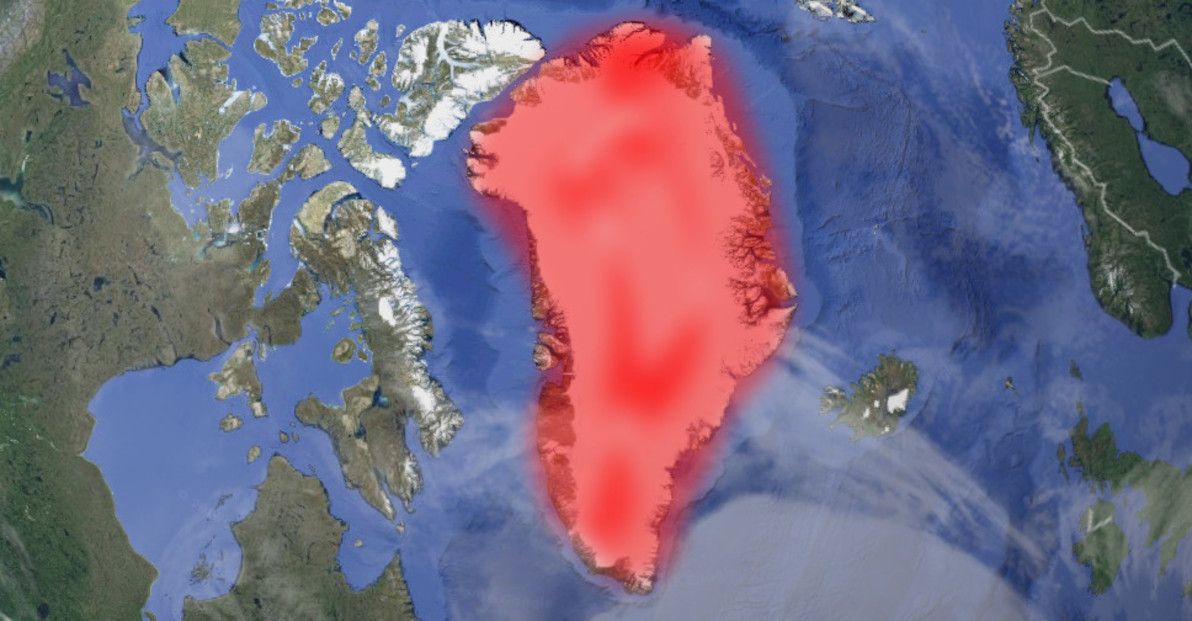

Greenland

Continuing east around the Arctic Circle, we come to Greenland, which is the largest contiguous and permanently-inhabited land mass in the world to have no roads at all between its settlements. Greenland is also the world's largest island.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The reason for the lack of road connections is the Greenland ice sheet, the second-largest body of ice in the world (after the Antarctic ice sheet), which covers 81% of the territory's surface. (And, as such, the answer to the age-old question "Is Greenland really green?", is overall "No!"). The only way to travel between Greenland's towns year-round is by air, with sea travel being possible only in summer, and dog sledding only in winter.

Svalbard

I'm generally avoiding covering small islands in this article, and am instead focusing on large continental areas. However, Svalbard (with Spitsbergen actually being the main island) is the largest island in the world – apart from islands that fall within other areas covered in this article – that has no roads between any of its settlements.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Svalbard is a Norwegian territory situated well north of the Arctic Circle. Its capital, Longyearbyen, is the northernmost city in the world. There are no roads linking Svalbard's handful of towns. Travel options involve air, sea, or snow.

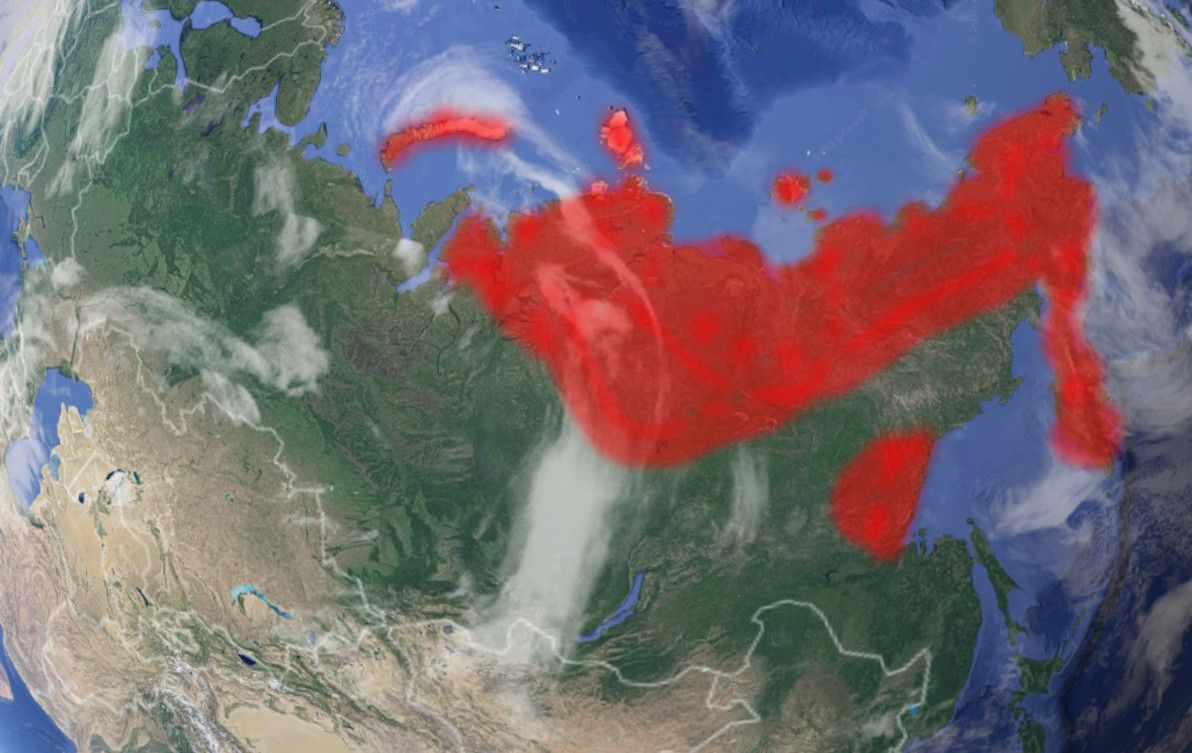

Siberia

The largest geographical region of the world's largest country (Russia), and well known as a vast "frozen wasteland", it should come as no surprise that Siberia features in this article. Siberia is the last of the arctic areas that I'll be covering here (indeed, if you continue east, you'll get back to Alaska, where I started). Consisting primarily of vast tracts of taiga and tundra, Siberia – particularly further north and further east – is a sparsely inhabited land of extreme cold and remoteness.

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Considering the size, the emptiness, and the often challenging terrain, Russia has actually made quite impressive achievements in building transport routes through Siberia. Starting with the late days of the Russian Empire, going strong throughout much of the Soviet Era, and continuing with the present-day Russian Federation, civilisation has slowly but surely made inroads (no pun intended) into the region.

North-west Russia – which actually isn't part of Siberia, being west of the Ural Mountains – is quite well-serviced by roads these days. There are two modern roads going north all the way to the Barents Sea: the R21 Highway to Murmansk, and the M8 route to Arkhangelsk. Further east, closer to the start of Siberia proper, there's a road up to Vorkuta, but it's apparently quite crude.

Crossing the Urals east into Siberia proper, Yamalo-Nenets has until fairly recently been quite lacking in land routes, particularly north of the capital Salekhard. However, that has changed dramatically of late in the remote (and sparsely inhabited) Yamal Peninsula, where there is still no proper road, but where the brand-new Obskaya-Bovanenkovo Railroad is operating. Purpose-built for the exploitation of what is believed to be the world's largest natural gas field, this is now the northernmost railway line in the world (and it's due to be extended even further north). Further up from Yamalo-Nenets, the islands of Novaya Zemlya are without land routes.

Image source: The Washington Post.

East of the Yamal Peninsula, the great roadless expanse of northern Siberia begins. In Krasnoyarsk Krai, the second-biggest geographical division in Russia, there are no real roads past the area more than a few hundred km's north of the city of Krasnoyarsk. Nothing, that is, except for the road and railway (until recently the world's northernmost) that reach the northern outpost of Norilsk; although neither road nor rail are properly connected to the rest of Russia.

The Sakha Republic, Russia's biggest geographical division, is completely roadless save for the main highway passing through its south-east corner, and its capital, Yakutsk. In the far north of Sakha, on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, the town of Tiksi is reckoned to be the most remote settlement in all of Russia. Here in the depths of Siberia, the main transport is via the region's mighty rivers, of which the Lena forms the backbone of Sakha. In winter, dog sleds and ice vehicles are the norm.

In the extreme north-east of Siberia, where Chukotka and the Kamchatka Peninsula can be found, there are no road routes whatsoever. Transport in these areas is solely by sea, air, or ice. The only road that comes close to these areas is the Kolyma Highway, also infamously known as the Road of Bones; this route has been improved in recent years, although it's still hair-raising for much of its length, and it's still one of the most remote highways in the world. There are also no roads to Okhotsk (which was the first and the only Russian settlement on the Pacific coast for many centuries), nor to anywhere else in northern Khabarovsk Krai.

Tibet

A part of the People's Republic of China (whether they like it or not) since 1951, Tibet has come a long way since the old days, when the entire kingdom did not have a single road. Today, China claims that 70% of all villages in Tibet are connected by road. And things have also stepped up quite a big notch, since the 2006 opening of the Trans-Tibetan Railway, which is a marvel of modern engineering, and is (at over 5,000m in one section) the new highest-altitude railway in the world.

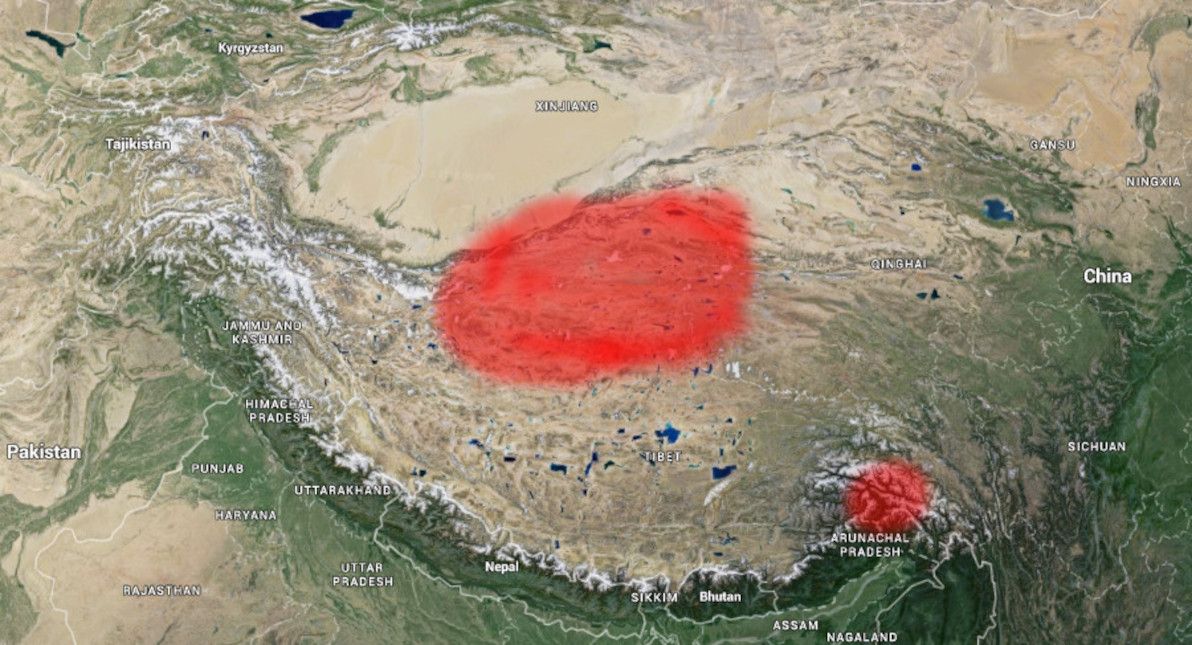

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Virtually the entire southern half of Tibet boasts a road network today. However, the central north area of the region – as well as a fair bit of adjacent terrain in neighbouring Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces – still appears to be without roads. This area also looks like it's devoid of any significant settlements, with nothing much around except high-altitude tundra.

Sahara

Leaving the (mostly icy) roadless realms of North America and Eurasia behind us, it's time to turn our attention southward, where the regions in question are more of a mixed bag. First up: the Sahara, the world's largest desert, which covers almost all of northern Africa, and which is virtually uninhabited save for its semi-arid fringes.

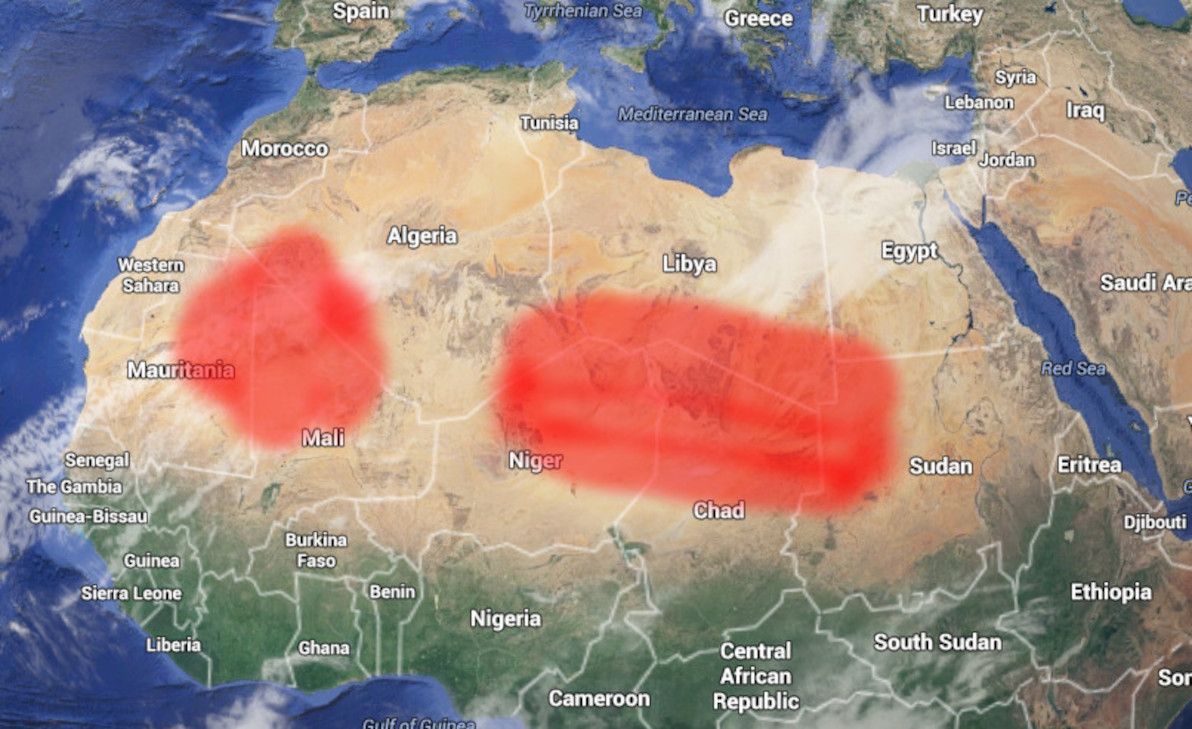

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

As the map shows, most of the parched interior of the Sahara is without roads. This includes: north-eastern Mauritania, northern Mali, south-eastern and south-western Algeria, northern Niger, southern Libya, northern Chad, north-west Sudan, and south-west Egypt. For all of the above, the only access is by air, by well-equipped 4WD convoy, or by camel caravan.

The only proper road cutting through this whole area, is the optimistically named Trans-Sahara Highway, the key part of which is the crossing from Agadez, Niger, north to Tamanrasset, Algeria. However, although most of the overall route (going all the way from Nigeria to Algeria) is paved, the section north of Agadez is still largely just a rough track through the sand, with occasional signposts indicating the way. There is also a rough track from Mali to Algeria (heading north from Kidal), but it appears to not be a proper road, even by Saharan standards.

Image source: Found the World.

I should also state (the obvious) here, namely that Saharan and Sub-Saharan Africa is not only one of the most arid and sparsely populated places on Earth, but that it's also one of the poorest, least developed, and most politically unstable places on Earth. As such, it should come as no surprise that overland travel through most of the roadless area is currently strongly discouraged, due to the security situation in many of the listed countries.

Australia

No run-down of the world's great roadless areas would be complete without including my sunburnt homeland, Australia. As I've blogged about before, there's a whole lot of nothing in the middle of this joint.

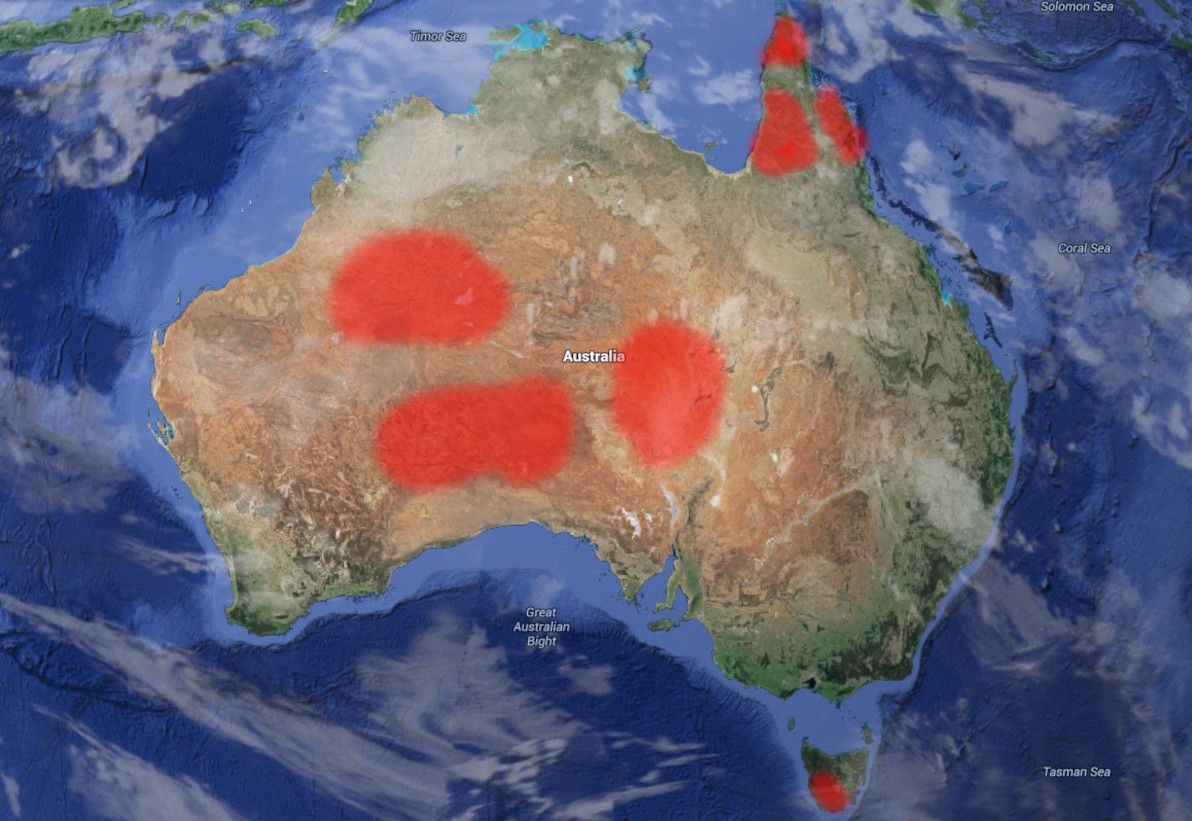

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

The biggest area of Australia to still lack road routes, is the heart of the Outback, in particular most of the east of Western Australia, and neighbouring land in the Northern Territory and South Australia. This area is bisected by only a single half-decent route (running east-west), the Outback Way – a route that is almost entirely unsealed – resulting in a north and a south chunk of roadless expanse.

The north chunk is centred on the Gibson Desert, and also includes large parts of the Great Sandy Desert and the Tanami Desert. The Gibson Desert, in particular, is considered to be the most remote place in Australia, and this is evidenced by its being where the last uncontacted Aboriginal tribe was discovered – those fellas didn't come outta the bush there 'til 1984. The south chunk consists of the Great Victoria Desert, which is the largest single desert in Australia, and which is similarly remote.

After that comes the area of Lake Eyre – Australia's biggest lake and, in typical Aussie style, one that seldom has any water in it – and the Simpson Desert to its north. The closest road to Lake Eyre itself is the Oodnadatta Track, and the only road that skirts the edge of the Simpson Desert is the Plenty Highway (which is actually part of the Outback Way mentioned above).

Image source: Avalook.

On the Apple Isle of Tasmania, the entire south-west region is an uninhabited, pristine, climatically extreme wilderness, and it's devoid of any roads at all. The only access is by sea or air: even 4WD is not an option in this hilly and forested area. Tasmania's famous South Coast Track bushwalk begins at the outpost of Melaleuca, where there is nothing except a small airstrip, and which can effectively only be reached by light aircraft. Not a trip for the faint-hearted.

Finally, in the extreme north-east of Australia, Cape York Peninsula remains one of the least accessible places on the continent, and has almost no roads (particularly the closer you get to the tip). The Peninsula Development Road, going as far north as Weipa, is the only proper road in the area: it's still largely unsealed, and like all other roads in the area, is closed and/or impassable for much of the year due to flooding. Up from there, Bamaga Road and the road to the tip are little more than rough tracks, and are only navigable by experienced 4WD'ers for a few months of the year. In this neck of the woods, you'll find that crocodiles, mosquitoes, jellyfish, and mud are much more common than roads.

New Zealand

Heading east across the ditch, we come to the Land of the Long White Cloud. The South Island of New Zealand is well-known for its dazzling natural scenery: crystal-clear rivers, snow-capped mountains, jutting fjords, mammoth glaciers, and rolling hills. However, all that doesn't make for areas that are particularly easy to live in, or to construct roads through.

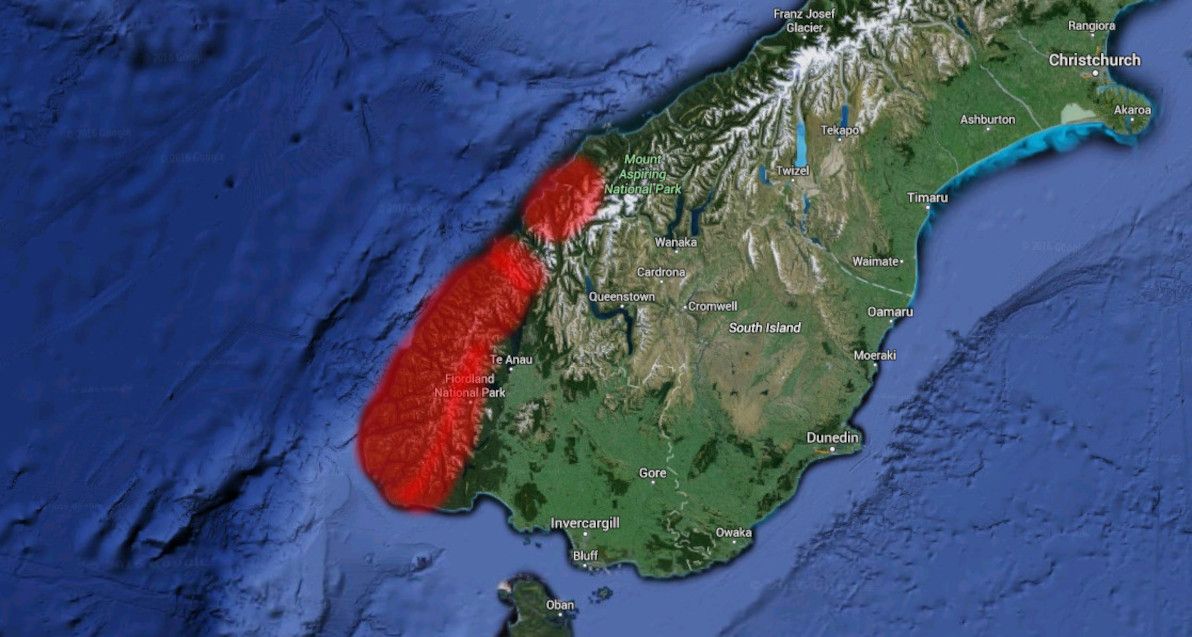

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Essentially, the entire south-west edge of NZ's South Island is without road access. In particular, all of Fiordland National Park: the whole area south of Milford Sound, and east of Te Anau. Same deal for Mount Aspiring National Park, between Milford Sound and Jackson Bay. The only exception is Milford Sound itself, which can be accessed via the famous Homer Tunnel, an engineering feat that pierces the walls of Fiordland against all odds.

Chile

You'd think that, being such a long and thin country, getting at least one road to traverse the entire length of Chile wouldn't be so hard. Think again. Chile is the world's longest north-south country, and spans a wide range of climatic zones, from hot dry desert in the north, to glacial fjord-land in the extreme south. If you've seen Chile desde Arica hasta Punta Arenas (as I have!), then you've witnessed first-hand the geographical variety that it has to offer.

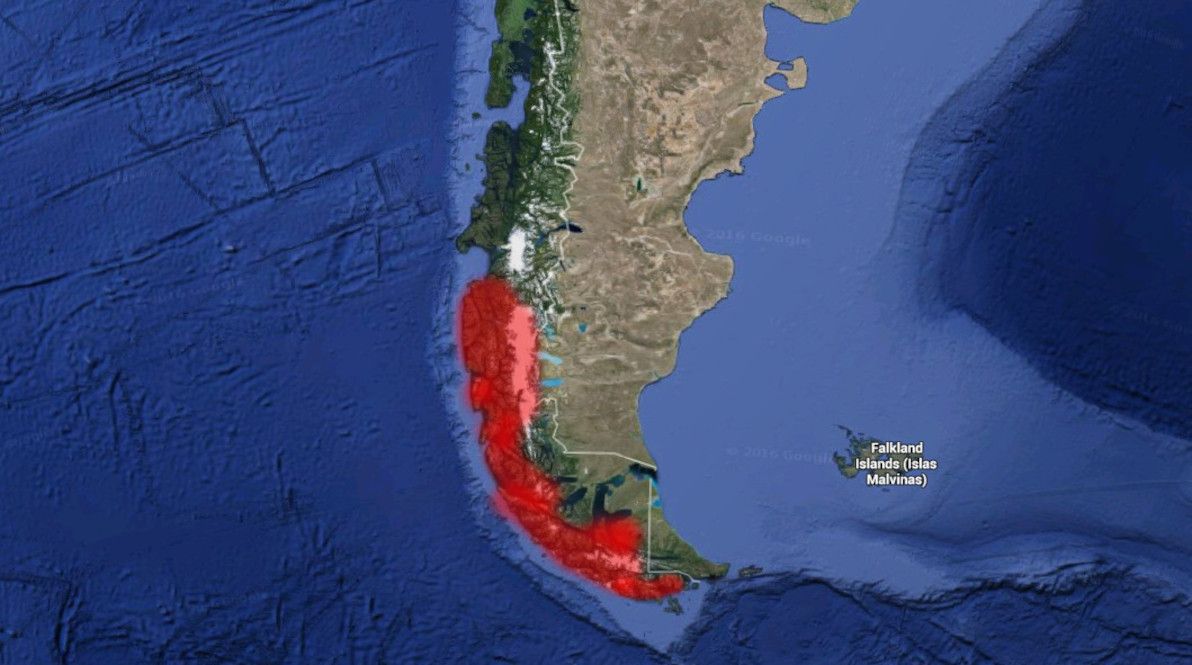

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Roads can be found in all of Chile, except for one area: in the far south, between Villa O'Higgins and Torres del Paine. That is, the southern-most portion of Región de Aysén, and the northern half of Región de Magallanes, are entirely devoid of roads. This is mainly on account of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, one of the world's largest chunks of ice outside of the polar regions. This ice field was only traversed on foot, for the first time in history, as recently as 1998; it truly is one of our planet's final unconquered frontiers. No road will be crossing it anytime soon.

Image source: Mallin Colorado.

Much of the Chilean side of the island of Tierra del Fuego is also without roads: this includes most of Parque Karukinka, and all of Parque Nacional Alberto de Agostini.

The Chilean government has for many decades maintained the monumental effort of extending the Carretera Austral ever further south. The route reached its current terminus at Villa O'Higgins in 2000. The ultimate aim, of course, is to connect isolated Magallanes (which to this day can only be reached by road via Argentina) with the rest of the country. But considering all the ice, fjords, and extreme conditions in the way, it might be some time off yet.

Amazon

We now come to what is by far the most lush and life-filled place in this article: the Amazon Basin. Spanning several South American countries, the Amazon is home to the world's largest river (by water volume) and river system. Although there are some big settlements in the area (including Iquitos, the world's biggest city that's not accessible by road), in general there are more piranhas and anacondas than there are people in this jungle (the piranhas help to keep it that way!).

Image source: Google Earth (red highlighting by yours truly).

Considering the challenges, quite a number of roads have actually been built in the Amazon in recent decades, particularly in the Brazilian part. The best-known of these is the Transamazônica, which – although rough and muddy as can be – has connected vast swaths of the jungle to civilisation. It should also be noted, that extensive road-building in this area is not necessarily a good thing: publicly-available satellite imagery clearly illustrates that, of the 20% of the Amazon that has been deforested to date, much of it has happened alongside roads.

The main parts of the Amazon that remain completely without roads are: western Estado do Amazonas and northern Estado do Pará in Brazil; most of north-eastern Peru (Departamento de Loreto); most of eastern Ecuador (the provinces in the Región amazónica del Ecuador); most of south-eastern Colombia (Amazonas, Vaupés, Guainía, Caquetá, and Guaviare departamentos); southern Venezuela (Estado de Amazonas); and the southern part of all the Guyanas (British Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana).

Image source: Getty Images.

The Amazon Basin probably already has more roads than it needs (or wants). In this part of the world, the rivers are the real highways – especially the Amazon itself, which has heavy marine traffic, despite being more than 5km wide in many parts (and that's in the dry season!). In fact, it's hard for terrestrial roads to compete with the rivers: for example, the BR-319 to Manaus has been virtually washed away by the jungle, and the main access to the Amazon's biggest city remains by boat.

Antarctica

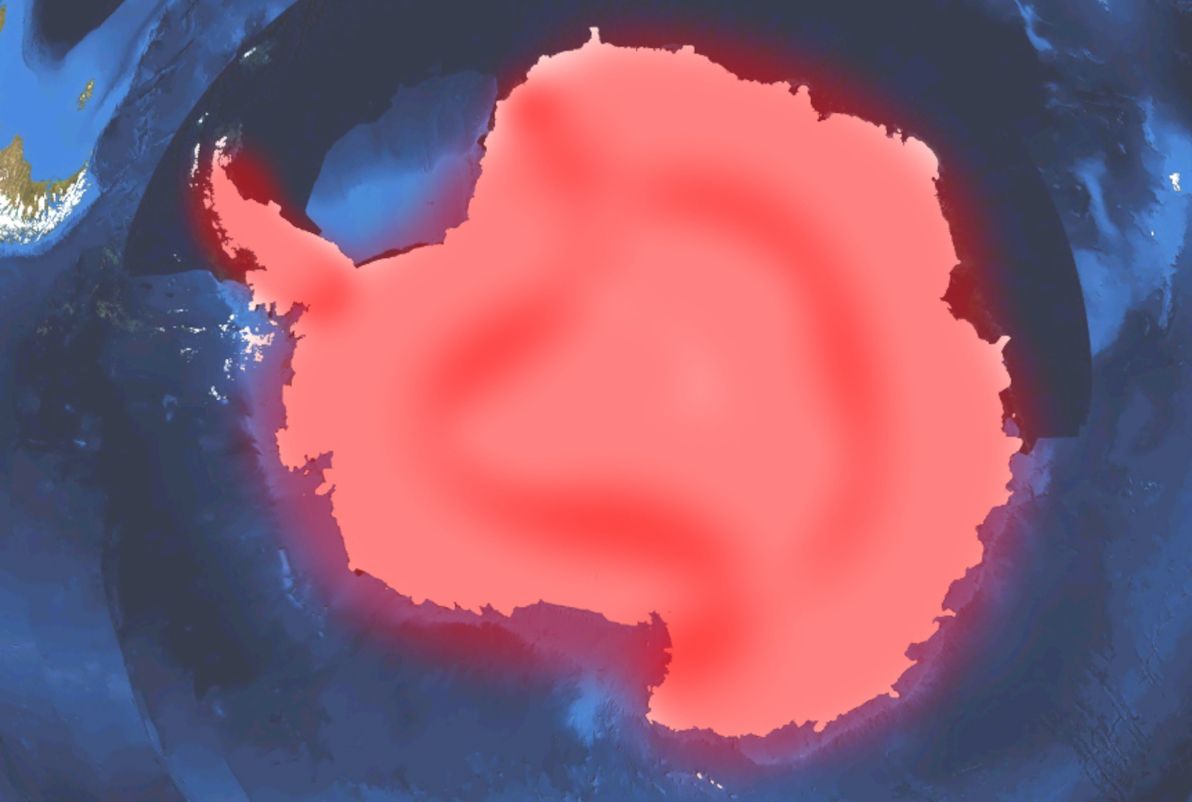

It's the world's fifth-largest continent. It's completely covered in ice. It has no permanent human population. It has no countries or (proper) territories. And it has no roads. And none of this should be a surprise to anyone!

Image source: Wikimedia Commons (red highlighting by yours truly).

As you might have guessed, not only are there no roads linking anywhere to anywhere else within Antarctica (except for ice trails), but (unlike every other area covered in this article) there aren't even any local roads within Antarctic settlements. The only regular access to Antarctica, and around Antarctica, is by air; even access by ship is difficult without helicopter support.

Where to?

There you have it: an overview of some of the most forlorn, desolate, but also beautiful places in the world, where the wonders of roads have never in all of human history been built. I've tried to cover as many relevant places as I can (and I've certainly covered more than I originally intended to), but of course I couldn't ever cover all of them. As I said, I've avoided discussion of islands, as a general rule, mainly because there is a colossal number of roadless islands around, and the list could go on forever.

I hope you've found this spin around the globe informative. And don't let such a minor inconvenience as a lack of roads stop you from visiting as many of these places as you can! Comments and feedback welcome.

]]>

Image source: Australian Outback Buffalo Safaris.

Over the past century or so, much has been achieved in combating the famous Tyranny of Distance that naturally afflicts this land. High-quality road, rail, and air links now traverse the length and breadth of Oz, making journeys between most of her far-flung corners relatively easy.

Nevertheless, there remain a few key missing pieces, in the grand puzzle of a modern, well-connected Australian infrastructure system. This article presents five such missing pieces, that I personally would like to see built in my lifetime. Some of these are already in their early stages of development, while others are pure fantasies that may not even be possible with today's technology and engineering. All of them, however, would provide a new long-distance connection between regions of Australia, where there is presently only an inferior connection in place, or none at all.

Tunnel to Tasmania

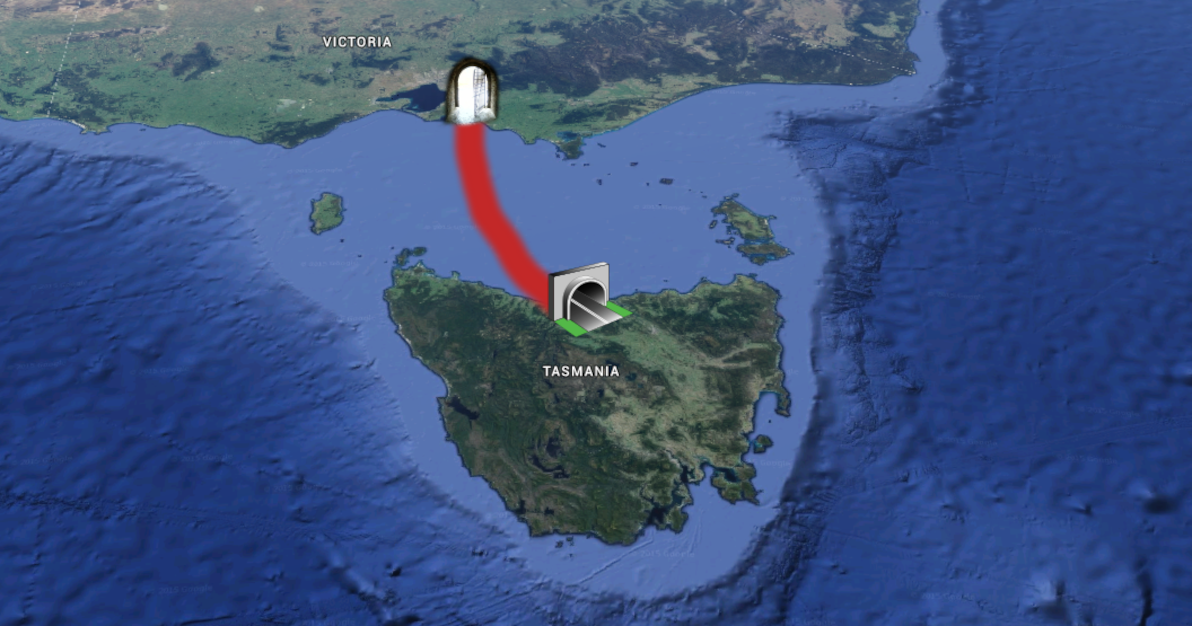

Let me begin with the most nut-brained idea of all: a tunnel from Victoria to Tasmania!

As the sole major region of Australia that's not on the continental landmass, currently the only options for reaching Tasmania are by sea or by air. The idea of a tunnel (or bridge) to Tasmania is not new, it has been sporadically postulated for over a century (although never all that seriously). There's a long and colourful discussion of routes, cost estimates, and geographical hurdles at the Bass Strait Tunnel thread on Railpage. There's even a Facebook page promoting a Tassie Tunnel.

Image sources: Wikimedia Commons: Light on door at the end of tunnel; Wikimedia Commons: Tunnel icon2; satellite imagery courtesy of Google Earth.

Although it would be a highly beneficial piece of infrastructure, that would in the long-term (among other things) provide a welcome boost to Tasmania's (and Australia's) economy, sadly the Tassie Tunnel is probably never going to happen. The world's longest undersea tunnel to date (under the Tsugaru Strait in Japan) spans only 54km. A tunnel under the Bass Strait, directly from Victoria to Tasmania, would be at least 200km long; although if it went via King Island (to the northwest of Tas), it could be done as two tunnels, each one just under 100km. Both the length and the depth of such a tunnel make it beyond the limits of contemporary engineering.

Aside from the engineering hurdle – and of course the monumental cost – it also turns out that the Bass Strait is Australia's main seismic hotspot (just our luck, what with the rest of Australia being seismically dead as a doornail). The area hasn't seen any significant undersea volcanic activity in the past few centuries, but experts warn that it could start letting off steam in the near future. This makes it hardly an ideal area for building a colossal tunnel.

Railway from Mt Isa to Tennant Creek

Great strides have been made in connecting almost all the major population centres of Australia by rail. The first significant long-distance rail link in Oz was the line from Sydney to Melbourne, which was completed in 1883 (although a change-of-gauge was required until 1962). The Indian Pacific (Sydney to Perth), a spectacular trans-continental achievement and the nation's longest train line – not to mention one of the great railways of the world – is the real backbone on the map, and has been operational since 1970. The newest and most long-awaited addition, The Ghan (Adelaide to Darwin), opened for business in 2004.

Image source: Fly With Me.

Today's nation-wide rail network (with regular passenger service) is, therefore, at an impressive all-time high. Every state and territory capital is connected (except for Hobart – a Tassie Tunnel would fix that!), and numerous regional centres are in the mix too. Despite the fact that many of the lines / trains are old and clunky, they continue (often stubbornly) to plod along.

If you look at the map, however, you might notice one particularly glaring gap in the network, particularly now that The Ghan has been established. And that is between Mt Isa in Queensland (the terminus of The Inlander service from Townsville), and Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory (which The Ghan passes through). At the moment, travelling continuously by rail from Townsville to Darwin would involve a colossal horse-shoe journey via Sydney and Adelaide, which only an utter nutter would consider embarking upon. Whereas with the addition of this relatively small (1,000km or so) extra line, the journey would be much shorter, and perfectly feasible. Although still long; there's no silver bullet through the outback.

A railway from Mt Isa to Tennant Creek – even though it would traverse some of the most remote and desolate land in Australia – is not a pipe dream. It's been suggested several times over the past few years. As with the development of the Townsville to Mt Isa railway a century ago, it will need the investment of the mining industry in order to actually happen. Unfortunately, the current economic situation means that mining companies are unlikely to invest in such a project at this time; what's more, The Inlander is a seriously decrepit service (at risk of being decommissioned) on an ageing line, making it somewhat unsuitable for joining up with a more modern line to the west.

Nonetheless, I have high hopes that we will see this railway connection built in the not-too-distant future, when the stars are next aligned.

Highway to Cape York

Australia's northernmost region, the Cape York Peninsula, is also one of the country's last truly wild frontiers. There is now a sealed all-weather highway all the way around the Australian mainland, and there's good or average road access to the key towns in almost all regional areas. Cape York is the only place left in Oz that lacks such roads, and that's also home to a non-trivial population (albeit a small 20,000-ish people, the majority Aborigines, in an area half the size of Victoria). Other areas in Oz with no road access whatsoever, such as south-west Tasmania, and most of the east of Western Australia, are lacking even a trivial population.

The biggest challenge to reliable transport in the Cape is the wet season: between December and April, there's so much rainfall that all the rivers become flooded, making roads everywhere impassable. Aside from that, the Cape also presents other obstacles, such as being seriously infested with crocodiles.

There are two main roads that provide access to the Cape: the Peninsula Developmental Road (PDR) from Lakeland to Weipa, and the Northern Peninsula Road (NPR), from the junction north of Coen on to Bamaga. The PDR is slowly improving, but the majority of it is still unsealed and is closed for much of the wet season. The NPR is worse: little (if any) of the route is sealed, and a ferry is required to cross the Jardine River (approaching the road's northern terminus), even at the height of the dry season.

Image source: Eco Citizen Australia.

A proper Cape York Highway, all the way from Lakeland to The Tip, is in my opinion bound to get built eventually. I've seen mention of a prediction that we should expect it done by 2050; if that estimate can be met, I'd call it a great achievement. To bring the Cape's main roads up to highway standard, they'd need to be sealed all the way, and there would need to be reasonably high bridges over all the rivers. Considering the very extreme weather patterns up that way, the route will never be completely flood-proof (much as the fully-sealed Barkly Highway through the Gulf of Carpentaria, south of the Cape, isn't flood-proof either); but if a journey all the way to The Tip were possible in a 2WD vehicle for most of the year, that would be a grand accomplishment.

High-speed rail on the Eastern seaboard

Of all the proposals being put forward here, this is by far the most well-known and the most oft talked about. Many Australians are in agreement with me, on the fact that a high-speed rail link along the east coast is sorely needed. Sydney to Canberra is generally touted as an appropriate first step, Sydney to Melbourne is acknowledged as the key component, and Sydney to Brisbane is seen as a very important extension.

There's a dearth of commentary out there regarding this idea, so I'll refrain from going into too much detail. In particular, the topic has been flooded with conversation since the fairly recent (2013) government-funded feasibility study (to the tune of AUD$20 million) into the matter.

Sadly, despite all the good news – the glowing recommendations of the government study; the enthusiasm of countless Australians; and some valiant attempts to stave off inertia – Australia has been waiting for high-speed rail an awfully long time, and it's probably going to have to keep on waiting. Because, with the cost of a complete Brisbane-Sydney-Canberra-Melbourne network estimated at around AUD$100 billion, neither the government nor anyone else is in a hurry to cough up the requisite cash.

This is the only proposal in this article, about an infrastructure link to complement another one (of the same mode) that already exists. I've tried to focus on links that are needed where currently there is nothing at all. However, I feel that this propoal belongs here, because despite its proud and important history, the ageing eastern seaboard rail network is rapidly becoming an embarrassment to the nation.

Image source: Adam Bandt MP.

The corner of Australia where 90% of the population live, deserves (and needs) a train service for the future, not one that belongs in a museum. The east coast interstate trains still run on diesel, as the lines aren't even electrified outside of the greater metropolitan areas. The network's few (remaining) passenger services share the line with numerous freight trains. There are still a plethora of old-fashioned level crossings. And the majority of the route is still single-track, causing regular delays and seriously limiting the line's capacity. And all this on two of the world's busiest air routes, with the road routes also struggling under the load.

Come on, Aussie – let's join the 21st century!

Self-sustaining desert towns

My final idea, some may consider a little kookoo, but I truly believe that it would be of benefit to our great sunburnt country. As should be clear by now, immense swathes of Australia are empty desert. There are many dusty roads and 4WD tracks traversing the country's arid centre, and it's not uncommon for some of the towns along these routes to be 1,000km's or more distant from their nearest neighbour. This results in communities (many of them indigenous) that are dangerously isolated from each other and from critical services; it makes for treacherous vehicle journeys, where travellers must bring extra necessities such as petrol and water, just to last the distance; and it means that Australia as a whole suffers from more physical disconnects, robbing contiguity from our otherwise unified land.

Image source: news.com.au.

Good transport networks (road and rail) across the country are one thing, but they're not enough. In my opinion, what we need to do is to string out more desert towns along our outback routes, in order to reduce the distances of no human contact, and of no basic services.

But how to support such towns, when most outback communities are struggling to survive as it is? And how to attract more people to these towns, when nobody wants to live out in the bush? In my opinion, with the help of modern technology and of alternative agricultural methods, it could be made to work.

Towns need a number of resources in order to thrive. First and foremost, they need water. Securing sufficient water in the outback is a challenge, but with comprehensive conservation rules, and modern water reuse systems, having at least enough water for a small population's residential use becomes feasible, even in the driest areas of Australia. They also need electricity, in order to use modern tools and appliances. Fortunately, making outback towns energy self-sufficient is easier than it's ever been before, thanks to recent breakthroughs in solar technology. A number of these new technologies have even been pilot-tested in the outback.

In order to be self-sustaining, towns also need to be able to cultivate their own food in the surrounding area. This is a challenge in most outback areas, where water is scarce and soil conditions are poor. Many remote communities rely on food and other basic necessities being trucked in. However, a number of recent initiatives related to desert greening may help to solve this thorny (as an outback spinifex) problem.

Most promising is the global movement (largely founded and based in Australia) known as permaculture. A permaculture-based approach to desert greening has enjoyed a vivid and well-publicised success on several occasions; most notably, Geoff Lawton's project in the Dead Sea Valley of Jordan about ten years ago. There has been some debate regarding the potential ability of permaculture projects to green the desert in Australia. Personally, I think that the pilot projects to date have been very promising, and that similar projects in Australia would be, at the least, a most worthwhile endeavour. There are also various other projects in Australia that aim to create or nurture green corridors in arid areas.

There are also crazy futuristic plans for metropolis-size desert habitats, although these fail to explain in detail how such habitats could become self-sustaining. And there are some interesting projects in place around the world already, focused on building self-sustaining communities.

As for where to build a new corridor of desert towns, my preference would be to target an area as remote and as spread-out as possible. For example, along the Great Central Road (which is part of the "Outback Highway"). This might be an overly-ambitious route, but it would certainly be one of the most suitable.

And regarding the "tough nut" of how to attract people to come and live in new outback towns – when it's hard enough already just to maintain the precarious existing population levels – I have no easy answer. It has been suggested that, with the growing number of telecommuters in modern industries (such as IT), and with other factors such as the high real estate prices in major cities, people will become increasingly likely to move to the bush, assuming there's adequately good-quality internet access in the respective towns. Personally, as an IT professional who has worked remotely on many occasions, I don't find this to be a convincing enough argument.

I don't think that there's any silver bullet to incentivising a move to new desert towns. "Candy dangling" approaches such as giving away free houses in the towns, equipping buildings with modern sustainable technologies, or even giving cash gifts to early pioneers – these may be effective in getting a critical mass of people out there, but it's unlikely to be sufficient to keep them there in the long-term. Really, such towns would have to develop a local economy and a healthy local business ecosystem in order to maintain their residents; and that would be a struggle for newly-built towns, the same as it's been a struggle for existing outback towns since day one.

In summary

Love 'em or hate 'em, admire 'em or attack 'em, there's my list of five infrastructure projects that I think would be of benefit to Australia. Some are more likely to happen than others; unfortunately, it appears that none of them is going to be fully realised any time soon. Feedback welcome!

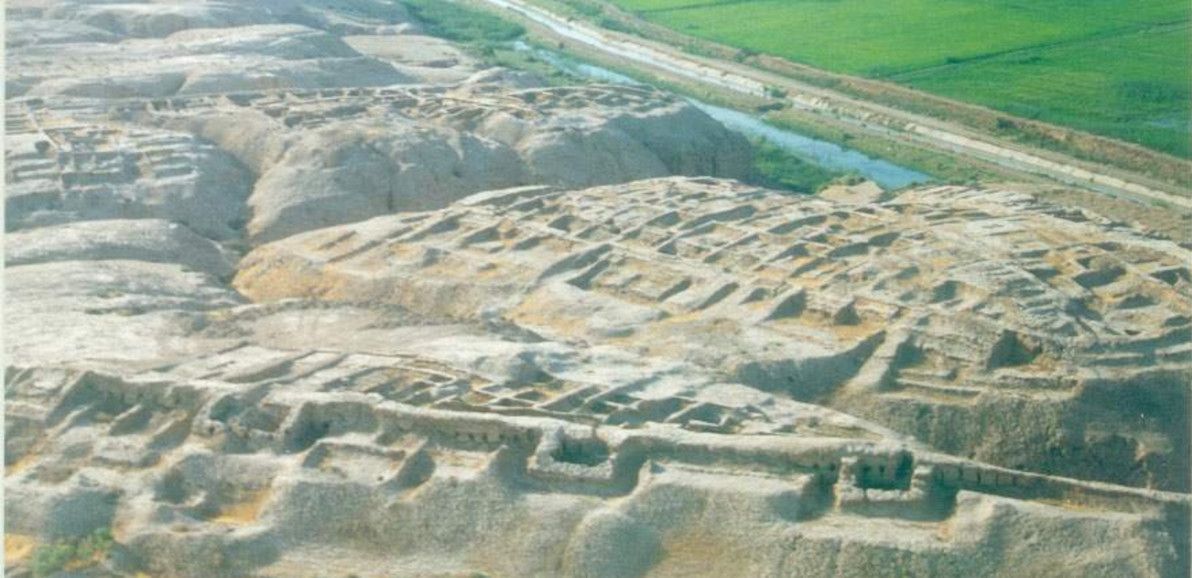

]]>The Oxus region is home to archaeological relics of grand civilisations, most notably of ancient Bactria, but also of Chorasmia, Sogdiana, Margiana, and Hyrcania. However, most of these ruined sites enjoy far less fame, and are far less well-studied, than comparable relics in other parts of the world.

I recently watched an excellent documentary series called Alexander's Lost World, which investigates the history of the Oxus region in-depth, focusing particularly on the areas that Alexander the Great conquered as part of his legendary military campaign. I was blown away by the gorgeous scenery, the vibrant cultural legacy, and the once-majestic ruins that the series featured. But, more than anything, I was surprised and dismayed at the extent to which most of the ruins have been neglected by the modern world – largely due to the region's turbulent history of late.

Image source: Stantastic: Back to Uzbekistan (Khiva).

This article has essentially the same aim as that of the documentary: to shed more light on the ancient cities and fortresses along the Oxus and nearby rivers; to get an impression of the cultures that thrived there in a bygone era; and to explore the climate change and the other forces that have dramatically affected the region between then and now.

Getting to know the rivers

First and foremost, an overview of the major rivers in question. Understanding the ebbs and flows of these arteries is critical, as they are the lifeblood of a mostly arid and unforgiving region.

Map: Forgotten realms of the Oxus region (Google Maps Engine). Satellite imagery courtesy of Google Earth.

The Oxus is the largest river (by water volume) in Central Asia. Due to various geographical factors, it's also changed its course more times (and more dramatically) than any other river in the region, and perhaps in the world.

The source of the Oxus is the Wakhan river, which begins at Baza'i Gonbad at the eastern end of Afghanistan's remote Wakhan Corridor, often nicknamed "The Roof of the World". This location is only 40km from the tiny and seldom-crossed Sino-Afghan border. Although the Wakhan river valley has never been properly "civilised" – neither by ancient empires nor by modern states (its population is as rugged and nomadic today as it was millenia ago) – it has been populated continuously since ancient times.

Next in line downstream is the Panj river, which begins where the Wakhan and Pamir rivers meet. For virtually its entire length, the Panj follows the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border; and it winds a zig-zag course through rugged terrain for much of its course, until it leaves behind the modern-day Badakhstan province towards its end. Like the Wakhan, the mountainous upstream part of the Panj was never truly conquered; however, the more accessible downstream part was the eastern frontier of ancient Bactria.

Image soure: Photos Khandud (Hava Afghanistan).

The Oxus proper begins where the Panj and Vakhsh rivers meet, on the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border. It continues along the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan border, and then along the Afghanistan-Turkmenistan border, until it enters Turkmenistan where the modern-day Karakum Canal begins. The river's course has been fairly stable along this part of the route throughout recorded history, although it has made many minor deviations, especially further downstream where the land becomes flatter. This part of the river was the Bactrian heartland in antiquity.

The rest of the river's route – mainly through Turkmenistan, but also hugging the Uzbek border in sections, and finally petering out in Uzbekistan – traverses the flat, arid Karakum Desert. The course and strength of the river down here has changed constantly over the centuries; for this reason, the Oxus has earned the nickname "the mad river". In ancient times, the Uzboy river branched off from the Oxus in northern Turkmenistan, and ran west across the desert until (arguably) emptying into the Caspian Sea. However, the strength of the Uzboy gradually lessened, until the river completely perished approximately 400 years ago. It appears that the Uzboy was considered part of the Oxus (and was given no name of its own) by many ancient geographers.

The Oxus proper breaks up into an extensive delta once in Uzbekistan; and for most of recorded history, it emptied into the Aral Sea. However, due to an aggressive Soviet-initiated irrigation campaign since the 1950s (the culmination of centuries of Russian planning and dreaming), the Oxus delta has rescinded significantly, and the river's waters fizzle out in the desert before reaching the sea. This is one of the major causes of the death of the Aral Sea, one of the worst environmental disasters on the planet.

Although geographically separate, the nearby Murghab river is also an important part of the cultural and archaeological story of the Oxus region (its lower reaches in modern-day Turkmenistan, at least). From its confluence with the Kushk river, the Murghab meanders gently down through semi-arid lands, before opening into a large delta that fans out optimistically into the unforgiving Karakum desert. The Murghab delta was in ancient times the heartland of Margiana, an advanced civilisation whose heyday largely predates that of Bactria, and which is home to some of the most impressive (and under-appreciated) archaeological sites in the region.

I won't be covering it in this article, as it's a whole other landscape and a whole lot more history; nevertheless, I would be remiss if I failed to mention the "sister" of the Oxus, the Syr Darya river, which was in antiquity known by its Greek name as the Jaxartes, and which is the other major artery of Central Asia. The source of the Jaxartes is (according to some) not far from that of the Oxus, high up in the Pamir mountains; from there, it runs mainly north-west through Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and then (for more than half its length) Kazakhstan, before approaching the Aral Sea from the east. Like the Oxus, the present-day Jaxartes also peters out before reaching the Aral; and since these two rivers were formerly the principal water sources of the Aral, that sea is now virtually extinct.

Hyrcania

Having finished tracing the rivers' paths from the mountains to the desert, I will now – Much like the documentary – explore the region's ancient realms the other way round, beginning in the desert lowlands.

The heartland of Hyrcania (more often absorbed into a map of ancient Parthia, than given its own separate mention) – in ancient times just as in the present-day – is Golestan province, Iran, which is a fertile and productive area on the south-west shores of the Caspian. This part of Hyrcania is actually outside of the Oxus region, and so falls off this article's radar. However, Hyrcania extended north into modern-day Turkmenistan, reaching the banks of the then-flowing Uzboy river (which was ambiguously referred to by Greek historians as the "Ochos" river).

Settlements along the lower Uzboy part of Hyrcania (which was on occasion given a name of its own, Nesaia) were few. The most notable surviving ruin there is the Igdy Kala fortress, which dates to approximately the 4th century BCE, and which (arguably) exhibits both Parthian and Chorasmian influence. Very little is known about Igdy Kala, as the site has seldom been formally studied. The question of whether the full length of the Uzboy ever existed remains unresolved, particularly regarding the section from Sarykamysh Lake to Igdy Kala.

By including Hyrcania in the Oxus region, I'm tentatively siding with those that assert that the "greater Uzboy" did exist; if it didn't (i.e. if the Uzboy finished in Sarykamysh Lake, and if the "lower Uzboy" was just a small inlet of the Caspian Sea), then the extent of cultural interchange between Hyrcania and the actual Oxus realms would have been minimal. In the documentary, narrator David Adams is quite insistent that the Oxus was connected to the Caspian in antiquity, making frequent reference to the works of Patrocles; while this was quite convenient for the documentary's hypothesis that the Oxo-Caspian was a major trade route, the truth is somewhat less black-and-white.

Chorasmia

North-east of Hyrcania, crossing the lifeless Karakum desert, lies Chorasmia, better known for most of its history as Khwarezm. Chorasmia lies squarely within the Oxus delta; although the exact location of its capitals and strongholds has shifted considerably over the centuries, due to political upheavals and due to changes in the delta's course. In antiquity (particularly in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE), Chorasmia was a vassal state of the Achaemenid Persian empire, much like the rest of the Oxus region; the heavily Persian-influenced language and culture of Chorasmia, which can still be faintly observed in modern times, harks back to this era.

This region was strongest in medieval times, and its medieval capital at the present-day ghost city of Konye-Urgench – known in its heyday as Gurganj – was Chorasmia's most significant seat of power. Gurganj was abandoned in the 16th century CE, when the Oxus changed course and left the once-fertile city and surrounds without water.

It's unknown exactly where antiquity-era Chorsamia was centred, although part of the ruins of Kyrk Molla at Gurganj date back to this period, as do part of the ruins of Itchan Kala in present-day Khiva (which was Khwarezm's capital from the 17th to the 20th centuries CE). Probably the most impressive and best-preserved ancient ruins in the region, are those of the Ayaz Kala fortress complex, parts of which date back to the 4th century BCE. There are numerous other "Kala" (the Chorasmian word for "fortress") nearby, including Toprak Kala and Kz'il Kala.

One of the less-studied sites – but by no means a less significant site – is Dev-kesken Kala, a fortress lying due west of Konye-Urgench, on the edge of the Ustyurt Plateau, overlooking the dry channel of the former upper Uzboy river. Much like Konye-Urgench (and various other sites in the lower Oxus delta), Dev-kesken Kala was abandoned when the water stopped flowing, in around the 16th century CE. The city was formerly known as Vazir, and it was a thriving hub of medieval Khwarezm. Also like other sites, parts of the fortress date back to the 4th century BCE.

Image source: Karakalpak: Devkesken qala and Vazir.

I should also note that Dev-kesken Kala was one of the most difficult archaeological sites (of all the sites I'm describing in this article) to find information online for. I even had to create the Dev-Kesken Wikipedia article, which previously didn't exist (my first time creating a brand-new page there). The site was also difficult to locate on Google Earth (should now be easier, the co-ordinates are saved on the Wikipedia page). The site is certainly under-studied and under-visited, considering its distinctive landscape and its once-proud history; however, it is remote and difficult to access, and I understand that this Uzbek-Turkmen frontier area is also rather unsafe, due to an ongoing border dispute.

Margiana

South of Chorasmia – crossing the Karakum desert once again – one will find the realm that in antiquity was known as Margiana (although that name is simply the hellenised version of the original Persian name Margu). Much like Chorasmia, Margiana is centred on a river delta in an otherwise arid zone; in this case, the Murghab delta. And like the Oxus delta, the Murghab delta has also dried up and rescinded significantly over the centuries, due to both natural and human causes. Margiana lies within what is present-day southern Turkmenistan.