It turns out that Chile has joined a small group of countries around the world, that have decided to implement a national IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) whitelist. From some quick investigation, as far as I can tell, the only other countries that boast such a system are Turkey, Azerbaijan, Colombia, and Nepal. Hardly the most venerable group of nations to be joining, in my opinion.

As someone who has been to Chile many times, all I can say is: not happy! Bringing your own mobile device, and purchasing a local SIM card, is the cheapest and the most convenient way to stay connected while travelling, and it's the go-to method for a great many tourists travelling all around the world. It beats international roaming hands-down, and it eliminates the unnecessary cost of purchasing a new local phone all the time. I really hope that the Chilean government reconsiders the need for this law, and I really hope that no more countries join this misguided bandwagon.

Image source: imgflip.

IMEI what?

In case you've never heard of an IMEI, and have no idea what it is, basically it's a unique identification code for all mobile phones worldwide. Historically, there have been no restrictions on the use of mobile handsets, in particular countries or worldwide, according to the device's IMEI code. On the contrary, what's much more common than the network blocking a device, is for the device itself to block access to all networks except one, due to it needing to be unlocked.

A number of countries have implemented IMEI blacklists, mainly in order to render stolen mobile devices useless – these countries include Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and numerous others. In my opinion, a blacklist is a much better solution than a whitelist in this domain, because it only places an administrative burden on problem devices, while all other devices on the network are presumed to be valid and authorised to connect.

Ostensibly, Chile has passed this law primarily to ensure that all mobiles imported and sold locally by retailers are capable of receiving emergency alerts (i.e. for natural disasters, particularly earthquakes and tsunamis), using a special system called SAE (Sistema de Alerta de Emergencias). In actual fact, the system isn't all that special – it's standard Cell Broadcast (CB) messaging, the vast majority of smartphones worldwide already support it, and registering IMEIs is not in any way required for it to function.

For example, the same technology is used for the Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) system in the USA, and for the Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) system in Japan, and neither of those countries have an IMEI whitelist in place. Chile uses channel 919 for its SAE broadcasts, which appears to be a standard emergency channel that's already used by The Netherlands and Israel (again, countries without an IMEI whitelist), and possibly also by other countries.

The new law is supposedly also designed to ensure (quoting the original Spanish text):

…que todos los equipos comercializados en el país informen con certeza al usuario si funcionarán o no en las diferentes localidades a lo largo de Chile, según las tecnologías que se comercialicen en cada zona geográfica.

Which translates to English as:

…that all commercially available devices in the country provide a guarantee to the user of whether they will function or not in all of the various regions throughout Chile, according to the technologies that are deployed within each geographical area.

However, that same article suggests that this is a solution to a problem that doesn't currently exist – i.e. that the vast majority of devices already work nationwide, and that Chile's mobile network technology is already sufficiently standardised nationwide. It also suggests that the real reason why this law was introduced, was simply in order to stifle the smaller, independent mobile retailers and service providers with a costly administrative burden, and thus to entrench the monopoly of Chile's big mobile companies (and there are approximately three big players on the scene).

So, it seems that the Chilean government created this law thinking purely of its domestic implications – and even those reasons are unsound, and appear to be mired in vested interests. And, as far as I can see, no thought at all was given to the gross inconvenience that this law was bound to cause, and that it is currently causing, to tourists. The fact that the Movistar Chile IMEI registration online form (which I used) requires that you enter a RUT (a Chilean national ID number, which most tourists including myself lack), exemplifies this utter obliviousness of the authorities and of the big telco companies, regarding visitors to Chile perhaps wanting to use their mobile devices as they see fit.

In summary

Chile is now one of a handful of countries where, as a tourist, despite bringing from home a perfectly good cellular device (i.e. one that's unlocked and that functions with all the relevant protocols and frequencies), the pig-headed bureaucracy of an IMEI whitelist makes the device unusable. So, my advice to anyone who plans to visit Chile and to purchase a local SIM card for your non-Chilean mobile phone: register your phone's IMEI well in advance of your trip, with one of the Chilean companies licensed to "certify" it (the procedure is at least free, for one device per person per year, and can be done online), and thus avoid the inconvenience of your device not working upon arrival in the country.

]]>There are plenty of articles round and about the interwebz, aimed more at the practical side of coming to Chile: i.e. tips regarding how to get around; lists of rough prices of goods / services; and crash courses in Chilean Spanish. There are also a number of commentaries on the cultural / social differences between Chile and elsewhere – on the national psyche, and on the political / economic situation.

My endeavour is to avoid this article from falling neatly into either of those categories. That is, I'll be covering some eccentricities of Chile that aren't practical tips as such, although knowing about them may come in handy some day; and I'll be covering some anecdotes that certainly reflect on cultural themes, but that don't pretend to paint the Chilean landscape inside-out, either.

Que disfrutiiy, po.

Image sources: Times Journeys / 2GB.

Fin de mes

Here in Chile, all that is money-related is monthly. You pay everything monthly (your rent, all your bills, all membership fees e.g. gym, school / university fees, health / home / car insurance, etc); and you get paid monthly (if you work here, which I don't). I know that Chile isn't the only country with this modus operandi: I believe it's the European system; and as far as I know, it's the system in various other Latin American countries too.

In Australia – and as far as I know, in most English-speaking countries – there are no set-in-stone rules about the frequency with which you pay things, or with which you get paid. Bills / fees can be weekly, monthly, quarterly, annual… whatever (although rent is generally charged and is talked about as a weekly cost). Your pay cheque can be weekly, fortnightly, monthly, quarterly… equally whatever (although we talk about "how much you earn" annually, even though hardly anyone is paid annually). I guess the "all monthly" system is more consistent, and I guess it makes it easier to calculate and compare costs. However, having grown up with the "whatever" system, "all monthly" seems strange and somewhat amusing to me.

In Chile, although payment due dates can be anytime throughout the month, almost everyone receives their salary at fin de mes (the end of the month). I believe the (rough) rule is: the dosh arrives on the actual last day of the month if it's a regular weekday; or the last regular weekday of the month, if the actual last day is a weekend or public holiday (which is quite often, since Chile has a lot of public holidays – twice as many as Australia!).

This system, combined with the last-minute / impulsive form of living here, has an effect that's amusing, frustrating, and (when you think about it) depressingly predictable. As I like to say (in jest, to the locals): in Chile, it's Christmas time every end-of-month! The shops are packed, the restaurants are overflowing, and the traffic is insane, on the last day and the subsequent few days of each month. For the rest of the month, all is quiet. Especially the week before fin de mes, which is really Struggle Street for Chileans. So extreme is this fin de mes culture, that it's even busy at the petrol stations at this time, because many wait for their pay cheque before going to fill up the tank.

This really surprised me during my first few months in Chile. I used to ask: ¿Qué pasa? ¿Hay algo important hoy? ("What's going on? Is something important happening today?"). To which locals would respond: Es fin de mes! Hoy te pagan! ("It's end-of-month! You get paid today!"). These days, I'm more-or-less getting the hang of the cycle; although I don't think I'll ever really get my head around it. I'm pretty sure that, even if we did all get paid on the same day in Australia (which we don't), we wouldn't all rush straight to the shops in a mad stampede, desperate to spend the lot. But hey, that's how life is around here.

Cuotas

Continuing with the socio-economic theme, and also continuing with the "all-monthly" theme: another Chile-ism that will never cease to amuse and amaze me, is the omnipresent cuotas ("monthly instalments"). Chile has seen a spectacular rise in the use of credit cards, over the last few decades. However, the way these credit cards work is somewhat unique, compared with the usual credit system in Australia and elsewhere.

Any time you make a credit card purchase in Chile, the cashier / shop assistant will, without fail, ask you: ¿cuántas cuotas? ("how many instalments?"). If you're using a foreign credit card, like myself, then you must always answer: sin cuotas ("no instalments"). This is because, even if you wanted to pay for your purchase in chunks over the next 3-24 months (and trust me, you don't), you can't, because this system of "choosing at point of purchase to pay in instalments" only works with local Chilean cards.

Chile's current president, the multi-millionaire Sebastian Piñera, played an important part in bringing the credit card to Chile, during his involvement with the banking industry before entering politics. He's also generally regarded as the inventor of the cuotas system. The ability to choose your monthly instalments at point of sale is now supported by all credit cards, all payment machines, all banks, and all credit-accepting retailers nationwide. The system has even spread to some of Chile's neighbours, including Argentina.

Unfortunately, although it seems like something useful for the consumer, the truth is exactly the opposite: the cuotas system and its offspring, the cuotas national psyche, has resulted in the vast majority of Chileans (particularly the less wealthy among them) being permanently and inescapably mired in debt. What's more, although some of the cuotas offered are interest-free (with the most typical being a no-interest 3-instalment plan), some plans and some cards (most notoriously the "department store bank" cards) charge exhorbitantly high interest, and are riddled with unfair and arcane terms and conditions.

Última hora

Chile's a funny place, because it's so "not Latin America" in certain aspects (e.g. much better infrastructure than most of its neighbours), and yet it's so "spot-on Latin America" in other aspects. The última hora ("last-minute") way of living definitely falls within the latter category.

In Chile, people do not make plans in advance. At least, not for anything social- or family-related. Ask someone in Chile: "what are you doing next weekend?" And their answer will probably be: "I don't know, the weekend hasn't arrived yet… we'll see!" If your friends or family want to get together with you in Chile, don't expect a phone call the week before. Expect a phone call about an hour before.

I'm not just talking about casual meet-ups, either. In Chile, expect to be invited to large birthday parties a few hours before. Expect to know what you're doing for Christmas / New Year a few hours before. And even expect to know if you're going on a trip or not, a few hours before (and if it's a multi-day trip, expect to find a place to stay when you arrive, because Chileans aren't big on making reservations).

This is in stark contrast to Australia, where most people have a calendar to organise their personal life (something extremely uncommon in Chile), and where most peoples' evenings and weekends are booked out at least a week or two in advance. Ask someone in Sydney what their schedule is for the next week. The answer will probably be: "well, I've got yoga tomorrow evening, I'm catching up with Steve for lunch on Wednesday, big party with some old friends on Friday night, beach picnic on Saturday afternoon, and a fancy dress party in the city on Saturday night." Plus, ask them what they're doing in two months' time, and they'll probably already have booked: "6 nights staying in a bungalow near Batemans Bay".

The última hora system is both refreshing and frustrating, for a planned-ahead foreigner like myself. It makes you realise just how regimented, inflexible, and lacking in spontenaeity life can be in your home country. But, then again, it also makes you tear your hair out, when people make zero effort to co-ordinate different events and to avoid clashes. Plus, it makes for many an awkward silence when the folks back home ask the question that everybody asks back home, but that nobody asks around here: "so, what are you doing next weekend?" Depends which way the wind blows.

Sit down

In Chile (and elsewhere nearby, e.g. Argentina), you do not eat or drink while standing. In most bars in Chile, everyone is sitting down. In fact, in general there is little or no "bar" area, in bars around here; it's all tables and chairs. If there are no tables or chairs left, people will go to a different bar, or wait for seats to become vacant before eating / drinking. Same applies in the home, in the park, in the garden, or elsewhere: nobody eats or drinks standing up. Not even beer. Not even nuts. Not even potato chips.

In Australia (and in most other English-speaking countries, as far as I know), most people eat and drink while standing, in a range of different contexts. If you're in a crowded bar or pub, eating / drinking / talking while standing is considered normal. Likewise for a big house party. Same deal if you're in the park and you don't want to sit on the grass. I know it's only a little thing; but it's one of those little things that you only realise is different in other cultures, after you've lived somewhere else.

It's also fairly common to see someone eating their take-away or other food while walking, in Australia. Perhaps some hot chips while ambling along the beach. Perhaps a sandwich for lunch while running (late) to a meeting. Or perhaps some lollies on the way to the bus stop. All stuff you wouldn't blink twice at back in Oz. In Chile, that is simply not done. Doesn't matter if you're in a hurry. It couldn't possibly be such a hurry, that you can't sit down to eat in a civilised fashion. The Chilean system is probably better for your digestion! And they have a point: perhaps the solution isn't to save time by eating and walking, but simply to be in less of a hurry?

Image source: Dondequieroir.

Walled and shuttered

One of the most striking visual differences between the Santiago and Sydney streetscapes, in my opinion, is that walled-up and shuttered-up buildings are far more prevalent in the former than in the latter. Santiago is not a dangerous city, by Latin-American or even by most Western standards; however, it often feels much less secure than it should, particularly at night, because often all you can see around you is chains, padlocks, and sturdy grilles. Chileans tend to shut up shop Fort Knox-style.

Walk down Santiago's Ahumada shopping strip in the evening, and none of the shopfronts can be seen. No glass, no lit-up signs, no posters. Just grey steel shutters. Walk down Sydney's Pitt St in the evening, and – even though all the shops close earlier than in Santiago – it doesn't feel like a prison, it just feels like a shopping area after-hours.

In Chile, virtually all houses and apartment buildings are walled and gated. Also, particularly ugly in my opinion, schools in Chile are surrounded by high thick walls. For both houses and schools, it doesn't matter if they're upper- or lower-class, nor what part of town they're in: that's just the way they build them around here. In Australia, on the other hand, you can see most houses and gardens from the street as you go past (and walled-in houses are criticised as being owned by "paranoid people"); same with schools, which tend to be open and abundant spaces, seldom delimiting their boundary with anything more than a low mesh fence.

As I said, Santiago isn't a particularly dangerous city, although it's true that robbery is far more common here than in Sydney. The real difference, in my opinion, is that Chileans simply don't feel safe unless they're walled in and shuttered up. Plus, it's something of a vicious cycle: if everyone else in the city has a wall around their house, and you don't, then chances are that your house will be targeted, not because it's actually easier to break into than the house next door (which has a wall that can be easily jumped over anyway), but simply because it looks more exposed. Anyway, I will continue to argue to Chileans that their country (and the world in general) would be better with less walls and less barriers; and, no doubt, they will continue to stare back at me in bewilderment.

Image source: eszsara (Flickriver).

In summary

So, there you have it: a few of my random observations about life in Santiago, Chile. I hope you've found them educational and entertaining. Overall, I've enjoyed my time in this city; and while I'm sometimes critical of and poke fun at Santiago's (and Chile's) peculiarities, I'm also pretty sure I'll miss then when I'm gone. If you have any conclusions of your own regarding life in this big city, feel free to share them below.

]]>Recently, I was looking for a list of all the official crossings between the two countries. Finding such a list, in clear and authoritative form, proved more difficult than I expected. Hence, one thing led to another; and before I knew it, I'd embarked upon a serious research mission to develop such a list myself. So, here it is — a list of all highway border crossings between Chile and Argentina, that are open to the general public.

Note: there's a legend at the end of the article.

Northern crossings

The northern part of the Chile-Argentina frontier is generally hot, dry, and slightly flatter at the top. I found the frontier's northern crossings to be the best-documented, and hence the easiest to research. They're also generally the easiest crossings to make, as they pose the least risk of being impassable due to snowstorms.

Of the northern crossings, the only one I've travelled on is Paso Jama; although I didn't go through the pass itself, I crossed into Chile from Laguna Verde in Bolivia, and cut into the Chilean part of the highway from there (as part of a 4WD tour of the Salar de Uyuni).

Chilean regions: II (Antofagasta), III (Atacama).

Argentine provinces: Jujuy, Salta, Catamarca, La Rioja.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Jama | S.P. de Atacama - S.S. de Jujuy | Main highway | |

| Paso Sico | Antofagasta - Salta | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Socompa | Antofagasta - Salta | Minor highway | |

| Paso San Francisco | Copiacó - S.F.V. de Catamarca | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Pircas Negras | Copiacó - La Rioja | Minor highway |

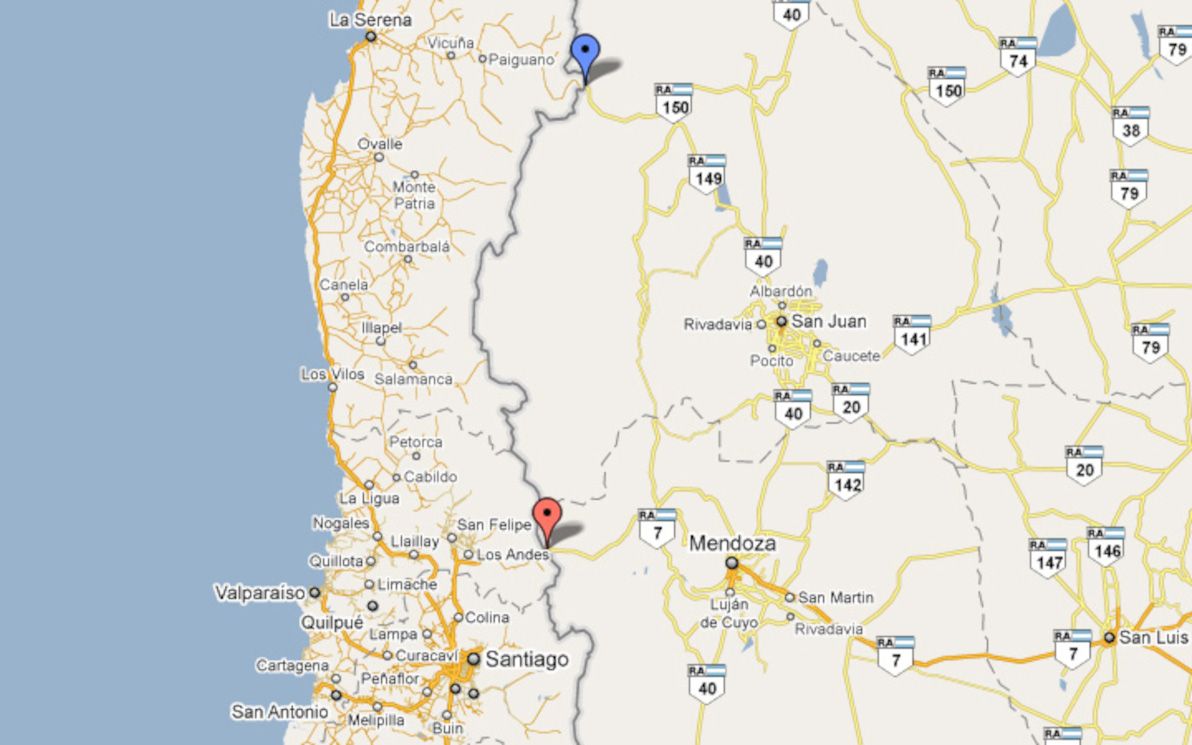

Central crossings

The Central part of the frontier is the most frequently crossed, as it's where you'll find the most direct route from Santiago to Buenos Aires. Unfortunately, Paso Los Libertadores is the only high-quality road in this entire section of the frontier — the mountains are particularly high, and construction of passes is particularly challenging, around here. After all, Aconcagua (the highest mountain in all the Americas) can be clearly seen right next to the main road.

As such, Los Libertadores is an extremely busy pass year-round; this is exacerbated by snowstorms forcing the pass to close during the height of winter, and also occasionally even in summer (despite there being a tunnel under the highest point of the route). I've travelled Los Libertadores twice (once in each direction), and it's a route with beautiful scenery; the zig-zags down the precipitous Chilean side of the pass are also quite hair-raising.

Chilean regions: IV (Coquimbo), V (Valparaíso).

Argentine provinces: San Juan, Mendoza.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Agua Negra | La Serena - San Juan | Minor highway | |

| Paso Los Libertadores | Santiago - Mendoza | Main highway |

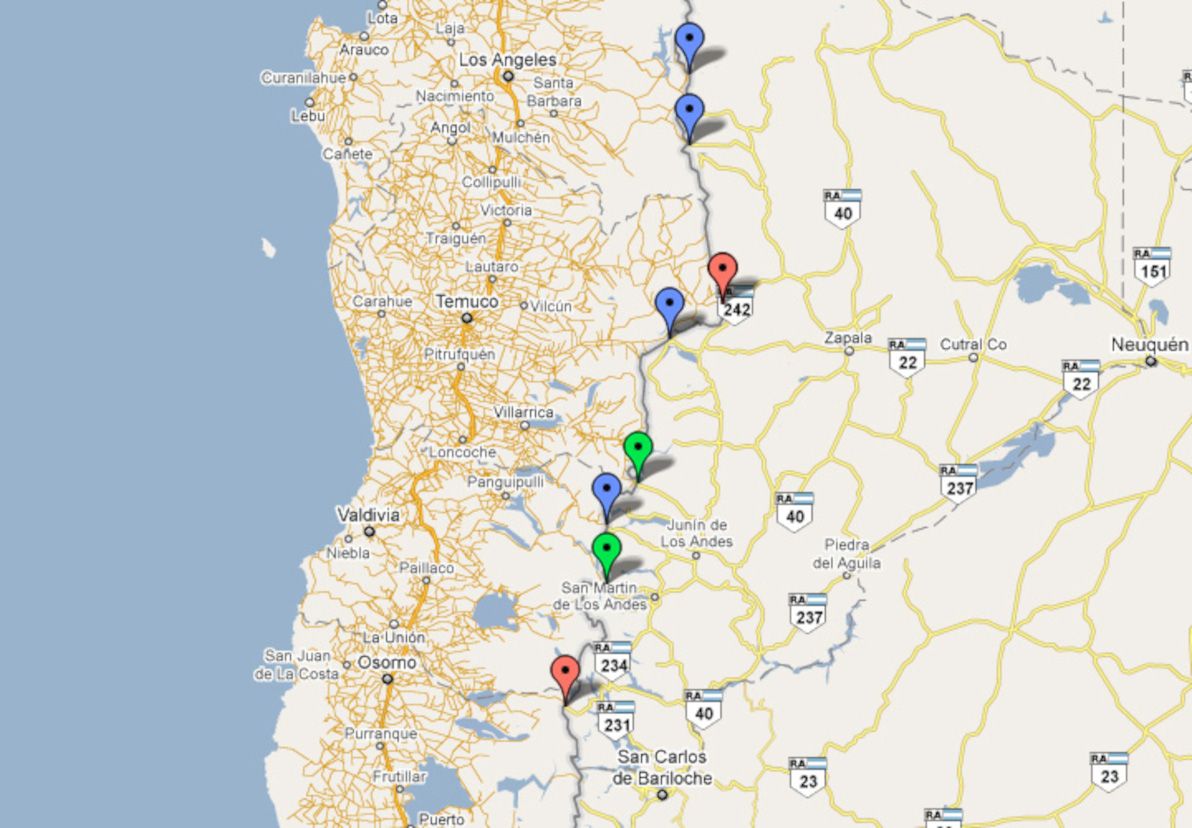

Lake district crossings

The lake districts of both Chile and Argentina are famed for their "Swiss Alps of the South" picturesque beauty, and the border crossings in this area are among the most spectacular of all vistas that the region has to offer. There are numerous border crossings in this area, most of which are quite good roads, and two of which are highway-grade.

Paso Cardenal Antonio Samoré is the only one down here that I've crossed. The roads here are all liable to close due to snow conditions; although I was lucky enough to cross in September with no problems.

I should also note that I've explicitly excluded the famous and beautiful Paso Pérez Rosales (Puerto Montt - S.C. de Bariloche) from the list here: this is because, although it's a paved highway-grade road the whole way, the highway is interrupted by a (long) lake crossing. I'm only including on this list crossings that can be made in one complete, uninterrupted land vehicle journey.

Chilean regions: VIII (Biobío), IX (Araucanía), XIV (Los Ríos).

Argentine provinces: Neuquén.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Pichachén | Los Angeles - Zapala | Minor highway | |

| Paso Copahue | Los Angeles - Zapala | Minor highway | |

| Paso Pino Hachado | Temuco - Neuquén | Main highway | |

| Paso Icalma | Temuco - Neuquén | Minor highway | |

| Paso Mamuil Malal | Pucón - Junín de L.A. | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Carirriñe | Coñaripe - Junin de L.A. | Minor highway | |

| Paso Huahum | Panguipulli - S.M. de Los Andes | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Cardenal Antonio Samoré | Osorno - S.C. de Bariloche | Main highway |

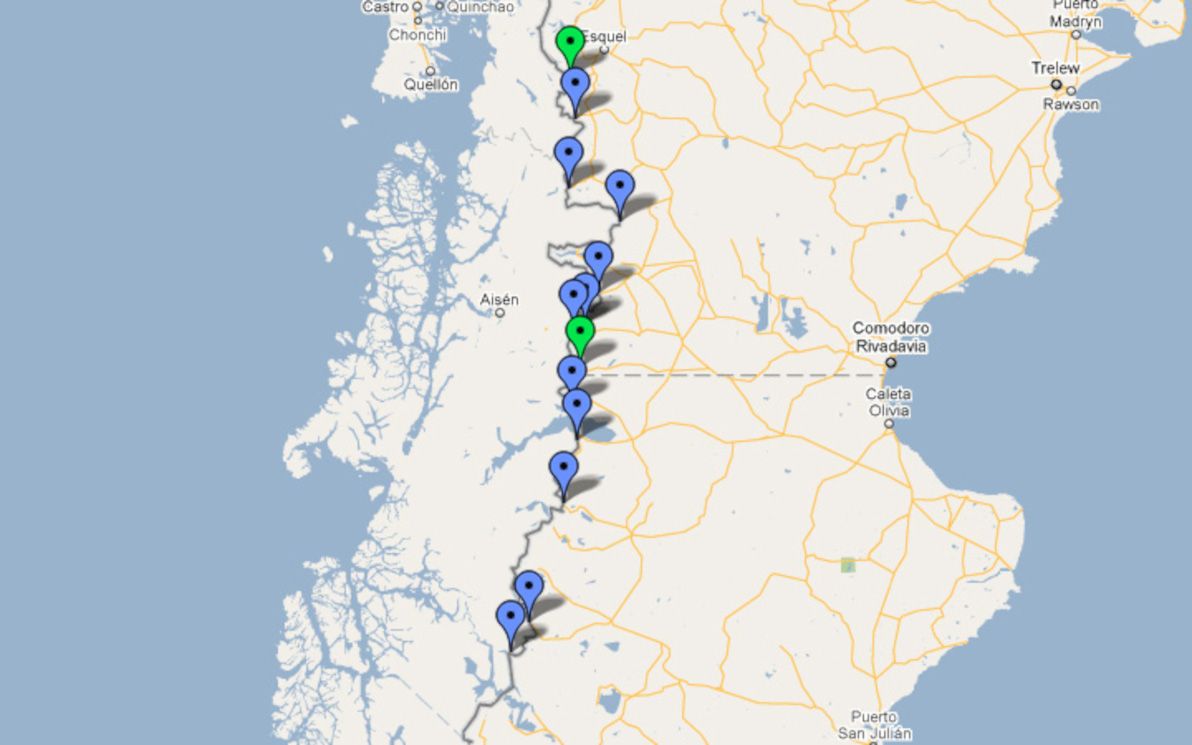

Southern crossings

These are the passes of the barren, empty pampas of Southern Patagonia. There are no main roads around here, and in some cases there are barely any towns for the roads to connect to, either. I haven't personally travelled any of these crossings, nor have I visited this part of Chile or Argentina at all.

Some of these highways go through rivers, with satellite imagery showing no bridges connecting the two sides; I can only assume that the rivers are passable in 4WD, assuming the water levels are low, or assuming the rivers are partly frozen. This was also by far the most difficult region to research: information about these passes is scarce and undetailed.

Chilean regions: X (Los Lagos), XI (Aisén).

Argentine provinces: Chubut, Santa Cruz.

| Name | Route | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Paso Futaleufu | Futaleufu - Esquel | Secondary highway |

| Paso Río Encuentro | Palena - Esquel | Minor highway |

| Paso Las Pampas | Cisnes - Esquel | Minor highway |

| Paso Río Frias | Cisnes - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Pampa Alta | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Coyhaique | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Triana | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Minor highway |

| Paso Huemules | Coyhaique - Comodoro Rivadavia | Secondary highway |

| Paso Ingeniero Ibáñez-Pallavicini | Puerto Ibáñez - Perito Moreno | Minor highway |

| Paso Río Jeinemeni | Puerto Guadal - Perito Moreno | Minor highway |

| Paso Roballos | Cochrane - Bajo Caracoles | Minor highway |

| Paso Rio Mayer Ribera Norte | O'Higgins - Las Horquetas | Minor highway |

| Paso Rio Mosco | O'Higgins - Las Horquetas | Minor highway |

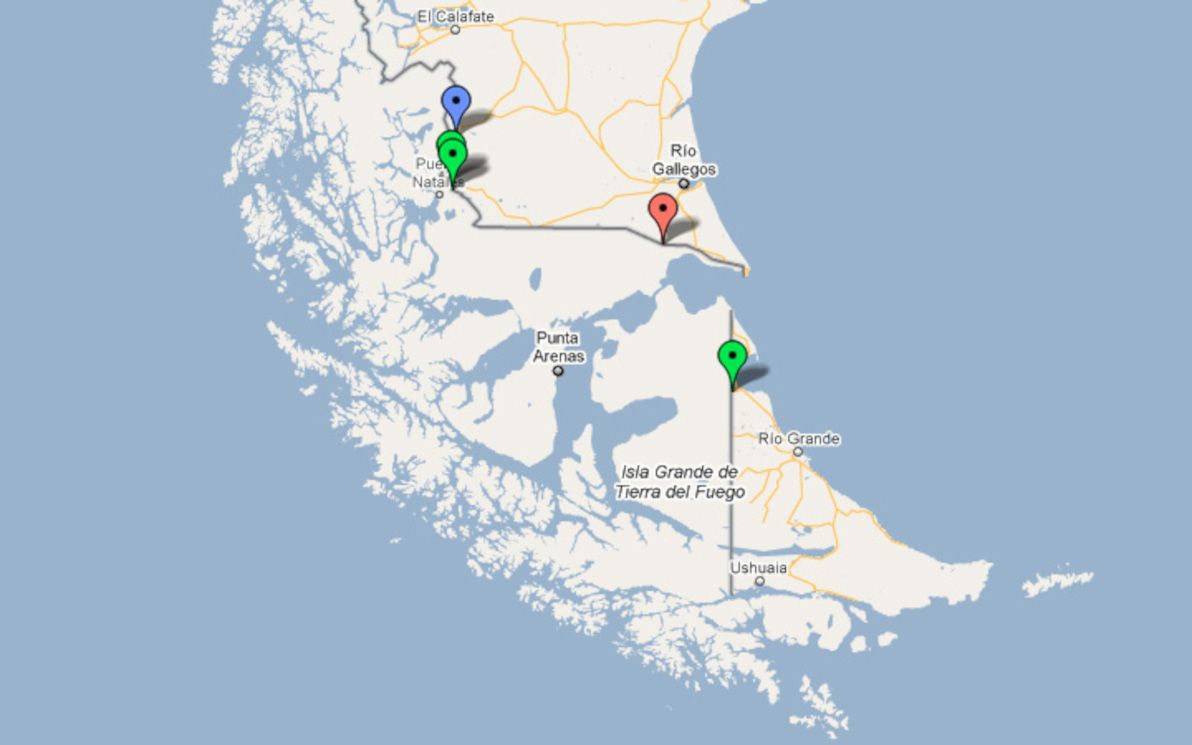

Extreme south crossings

The passes of the extreme south are easily crossed when weather conditions are good, as the mountains are much lower down here (or are basically plateaus). In winter, however, land transport is seldom an option. There is one main road in the extreme south, connecting Punta Arenas and Rio Gallegos.

The only crossing I've made in the extreme south is through Paso Rio Don Guillermo, which is unsealed and is little more than a cattle track (although it's pretty straight and flat). The buses from Puerto Natales to El Calafate use this pass: the entrance to the road has a chain across it on both ends, which is unlocked by border police to let the buses through.

Chilean regions: XII (Magallanes).

Argentine provinces: Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego.

| Name | Route | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paso Rio Don Guillermo | Puerto Natales - El Calafate | Minor highway | |

| Paso Dorotea | Puerto Natales - Rio Gallegos | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Laurita - Casas Vieja | Puerto Natales - Rio Gallegos | Secondary highway | |

| Paso Integración Austral | Punta Arenas - Río Gallegos | Main highway | |

| Paso San Sebastián | Porvenir - Rio Grande | Secondary highway |

Legend

Note: here's a link to the Google Map of Chile - Argentina border crossings that is referenced throughout this article.

Main highway

- Red markers on map

- Fully paved

- Public bus services

- Open almost year-round

- Customs and immigration integrated into the crossing

- Constant traffic

Secondary highway

- Green markers on map

- Partially paved

- Little or no public bus services

- Possibly closed some or most of the year

- Customs and immigration possibly integrated into the crossing

- Lesser or seasonal traffic

Minor highway

- Blue markers on map

- Unpaved

- No public bus services, and/or only open for authorised vehicles

- Not open year-round

- Customs and immigration must be done before and/or after the crossing

- Little or no traffic

Additional references

- Chilean government's list of permanent border crossings

- Wikipedia's list of all Argentine border crossings

- Wikipedia's list of countries and territories by land borders

- Viva travel guides: lakes district border crossings

- Neuquén tourism's border crossings list

- Look Patagonia's list of border crossings in Argentine Neuquén province

- Look Patagonia's list of border crossings in Argentine Chubut province

- Interpatagonia's list of passes that lead to Coyhaique