I was also surprised to learn, after doing a modest bit of research, that Tolstoy is seldom mentioned amongst any of the prominent figures in philosophy or metaphysics over the past several centuries. The only articles that even deign to label Tolstoy as a philosopher, are ones that are actually more concerned with Tolstoy as a cult-inspirer, as a pacifist, and as an anarchist.

So, while history has been just and generous in venerating Tolstoy as a novelist, I feel that his contribution to the field of philosophy has gone unacknowledged. This is no doubt in part because Tolstoy didn't consider himself a philosopher, and because he didn't pen any purely philosophical works (published separately from novels and other works), and because he himself criticised the value of such works. Nevertheless, I feel warranted in asking: is Tolstoy a forgotten philosopher?

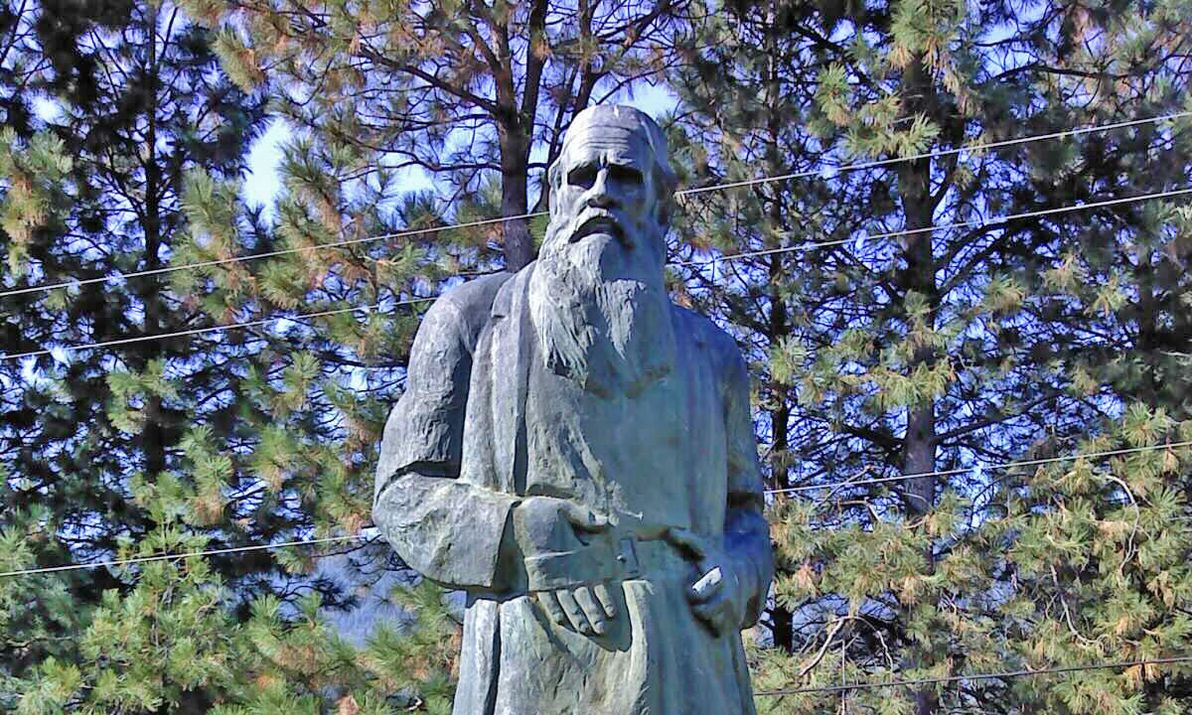

Image source: Waymarking

Free will in War and Peace

The concept of free will that Tolstoy articulates in War and Peace (particularly in the second epilogue), in a nutshell, is that there are two forces that influence every decision at every moment of a person's life. The first, free will, is what resides within a person's mind (and/or soul), and is what drives him/her to act per his/her wishes. The second, necessity, is everything that resides external to a person's mind / soul (that is, a person's body is also for the most part considered external), and is what strips him/her of choices, and compels him/her to act in conformance with the surrounding environment.

Whatever presentation of the activity of many men or of an individual we may consider, we always regard it as the result partly of man's free will and partly of the law of inevitability.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

A simple example that would appear to demonstrate acting completely according to free will: say you're in an ice cream parlour (with some friends), and you're tossing up between getting chocolate or hazelnut. There's no obvious reason why you would need to eat one flavour vs another. You're partial to both. They're both equally filling, equally refreshing, and equally (un)healthy. You'll be able to enjoy an ice cream with your friends regardless. You're free to choose!

You say: I am not and am not free. But I have lifted my hand and let it fall. Everyone understands that this illogical reply is an irrefutable demonstration of freedom.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter VIII

And another simple example that would appear to demonstrate being completely overwhelmed by necessity: say there's a gigantic asteroid on a collision course for Earth. It's already entered the atmosphere. You're looking out your window and can see it approaching. It's only seconds until it hits. There's no obvious choice you can make. You and all of humanity are going to die very soon. There's nothing you can do!

A sinking man who clutches at another and drowns him; or a hungry mother exhausted by feeding her baby, who steals some food; or a man trained to discipline who on duty at the word of command kills a defenseless man – seem less guilty, that is, less free and more subject to the law of necessity, to one who knows the circumstances in which these people were placed …

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

However, the main point that Tolstoy makes regarding these two forces, is that neither of them does – and indeed, neither of them can – ever exist in absolute form, in the universe as we know it. That is to say, a person is never (and can never be) free to decide anything 100% per his/her wishes; and likewise, a person is never (and can never be) shackled such that he/she is 100% compelled to act under the coercion of external agents. It's a spectrum! And every decision, at every moment of a person's life (and yes, every moment of a person's life involves a decision), lies somewhere on that spectrum. Some decisions are made more freely, others are more constrained. But all decisions result from a mix of the two forces.

In neither case – however we may change our point of view, however plain we may make to ourselves the connection between the man and the external world, however inaccessible it may be to us, however long or short the period of time, however intelligible or incomprehensible the causes of the action may be – can we ever conceive either complete freedom or complete necessity.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter X

So, going back to the first example: there are always some external considerations. Perhaps there's a little bit more chocolate than hazelnut in the tubs, so you'll feel just that little bit guilty if you choose the hazelnut, that you'll be responsible for the parlour running out of it, and for somebody else missing out later. Perhaps there's a deal that if you get exactly the same ice cream five times, you get a sixth one free, and you've already ordered chocolate four times before, so you feel compelled to order it again this time. Or perhaps you don't really want an ice cream at all today, but you feel that peer pressure compels you to get one. You're not completely free after all!

If we consider a man alone, apart from his relation to everything around him, each action of his seems to us free. But if we see his relation to anything around him, if we see his connection with anything whatever – with a man who speaks to him, a book he reads, the work on which he is engaged, even with the air he breathes or the light that falls on the things about him – we see that each of these circumstances has an influence on him and controls at least some side of his activity. And the more we perceive of these influences the more our conception of his freedom diminishes and the more our conception of the necessity that weighs on him increases.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter IX

And, going back to the second example: you always have some control over your own destiny. You have but a few seconds to live. Do you cower in fear, flat on the floor? Do you cling to your loved one at your side? Do you grab a steak knife and hurl it defiantly out the window at the approaching asteroid? Or do you stand there, frozen to the spot, staring awestruck at the vehicle of your impending doom? It may seem pointless, weighing up these alternatives, when you and your whole world are about to be pulverised; but aren't your last moments in life, especially if they're desperate last moments, the ones by which you'll be remembered? And how do you know for certain that there will be nobody left to remember you (and does that matter anyway)? You're not completely bereft of choices after all!

… even if, admitting the remaining minimum of freedom to equal zero, we assumed in some given case – as for instance in that of a dying man, an unborn babe, or an idiot – complete absence of freedom, by so doing we should destroy the very conception of man in the case we are examining, for as soon as there is no freedom there is also no man. And so the conception of the action of a man subject solely to the law of inevitability without any element of freedom is just as impossible as the conception of a man's completely free action.

War and Peace, second epilogue, chapter X

Background story

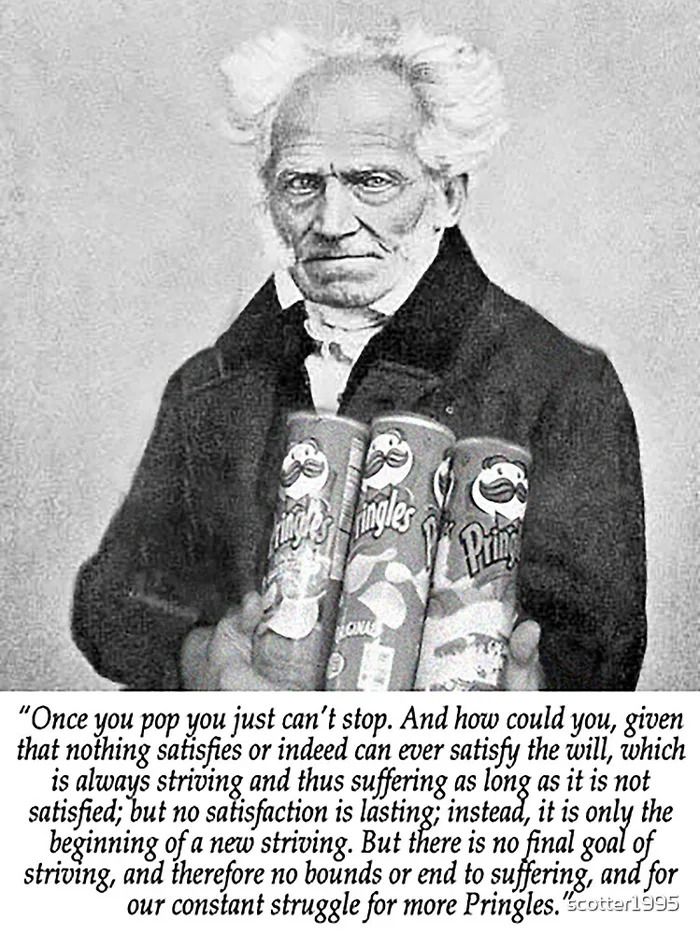

Tolstoy's philosophical propositions in War and Peace were heavily influenced by the ideas of one of his contemporaries, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. In later years, Tolstoy candidly expressed his admiration for Schopenhauer, and he even went so far as to assert that, philosophically speaking, War and Peace was a repetition of Schopenhauer's seminal work The World as Will and Representation.

Schopenhauer's key idea, was that the whole universe (at least, as far as any one person is concerned) consists of two things: the will, which doesn't exist in physical form, but which is the essence of a person, and which contains all of one's drives and desires; and the representation, which is a person's mental model of all that he/she has sensed and interacted with in the physical realm. However, rather than describing the will as the engine of one's freedom, Schopenhauer argues that one is enslaved by the desires imbued in his/her will, and that one is liberated from the will (albeit only temporarily) by aesthetic experience.

Image source: 9gag

Schopenhauer's theories were, in turn, directly influenced by those of Immanuel Kant, who came a generation before him, and who is generally considered the greatest philosopher of the modern era. Kant's ideas (and his works) were many (and I have already written about Kant's ideas recently), but the one of chief concern here – as expounded primarily in his Critique of Pure Reason – was that there are two realms in the universe: the phenomenal, that is, the physical, the universe as we experience and understand it; and the noumenal, that is, a theoretical non-material realm where everything exists as a "thing-in-itself", and about which we know nothing, except for what we are able to deduce via practical reason. Kant argued that the phenomenal realm is governed by absolute causality (that is, by necessity), but that in the noumenal realm there exists absolute free will; and that the fact that a person exists in both realms simultaneously, is what gives meaning to one's decisions, and what makes them able to be measured and judged in terms of ethics.

We can trace the study of free will further through history, from Kant, back to Hume, to Locke, to Descartes, to Augustine, and ultimately back to Plato. In the writings of all these fine folks, over the millennia, there can be found common concepts such as a material vs an ideal realm, a chain of causation, and a free inner essence. The analysis has become ever more refined with each passing generation of metaphysics scholars, but ultimately, it has deviated very little from its roots in ancient times.

It's unique

There are certainly parallels between Tolstoy's War and Peace, and Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation (and, in turn, with other preceding works), but I for one disagree that the former is a mere regurgitation of the latter. Tolstoy is selling himself short. His theory of free will vs necessity is distinct from that of Schopenhauer (and from that of Kant, for that matter). And the way he explains his theory – in terms of a "spectrum of free-ness" – is original as far as I'm aware, and is laudable, if for no other reason, simply because of how clear and easy-to-grok it is.

It should be noted, too, that Tolstoy's philosophical views continued to evolve significantly, later in his life, years after writing War and Peace. At the dawn of the 1900s (by which time he was an old man), Tolstoy was best known for having established his own "rational" version of Christianity, which rejected all the rituals and sacraments of the Orthodox Church, and which gained a cult-like following. He also adopted the lifestyle choices – extremely radical at the time – of becoming vegetarian, of renouncing violence, and of living and dressing like a peasant.

Image source: Flickr

War and Peace is many things. It's an account of the Napoleonic Wars, its bloody battles, its geopolitik, and its tremendous human cost. It's a nostalgic illustration of the old Russian aristocracy – a world long gone – replete with lavish soirees, mountains of servants, and family alliances forged by marriage. And it's a tenderly woven tapestry of the lives of the main protagonists – their yearnings, their liveliest joys, and their deepest sorrows – over the course of two decades. It rightly deserves the praise that it routinely receives, for all those elements that make it a classic novel. But it also deserves recognition for the philosophical argument that Tolstoy peppers throughout the text, and which he dedicates the final pages of the book to making more fully fledged.

]]>The Oxus region is home to archaeological relics of grand civilisations, most notably of ancient Bactria, but also of Chorasmia, Sogdiana, Margiana, and Hyrcania. However, most of these ruined sites enjoy far less fame, and are far less well-studied, than comparable relics in other parts of the world.

I recently watched an excellent documentary series called Alexander's Lost World, which investigates the history of the Oxus region in-depth, focusing particularly on the areas that Alexander the Great conquered as part of his legendary military campaign. I was blown away by the gorgeous scenery, the vibrant cultural legacy, and the once-majestic ruins that the series featured. But, more than anything, I was surprised and dismayed at the extent to which most of the ruins have been neglected by the modern world – largely due to the region's turbulent history of late.

Image source: Stantastic: Back to Uzbekistan (Khiva).

This article has essentially the same aim as that of the documentary: to shed more light on the ancient cities and fortresses along the Oxus and nearby rivers; to get an impression of the cultures that thrived there in a bygone era; and to explore the climate change and the other forces that have dramatically affected the region between then and now.

Getting to know the rivers

First and foremost, an overview of the major rivers in question. Understanding the ebbs and flows of these arteries is critical, as they are the lifeblood of a mostly arid and unforgiving region.

Map: Forgotten realms of the Oxus region (Google Maps Engine). Satellite imagery courtesy of Google Earth.

The Oxus is the largest river (by water volume) in Central Asia. Due to various geographical factors, it's also changed its course more times (and more dramatically) than any other river in the region, and perhaps in the world.

The source of the Oxus is the Wakhan river, which begins at Baza'i Gonbad at the eastern end of Afghanistan's remote Wakhan Corridor, often nicknamed "The Roof of the World". This location is only 40km from the tiny and seldom-crossed Sino-Afghan border. Although the Wakhan river valley has never been properly "civilised" – neither by ancient empires nor by modern states (its population is as rugged and nomadic today as it was millenia ago) – it has been populated continuously since ancient times.

Next in line downstream is the Panj river, which begins where the Wakhan and Pamir rivers meet. For virtually its entire length, the Panj follows the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border; and it winds a zig-zag course through rugged terrain for much of its course, until it leaves behind the modern-day Badakhstan province towards its end. Like the Wakhan, the mountainous upstream part of the Panj was never truly conquered; however, the more accessible downstream part was the eastern frontier of ancient Bactria.

Image soure: Photos Khandud (Hava Afghanistan).

The Oxus proper begins where the Panj and Vakhsh rivers meet, on the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border. It continues along the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan border, and then along the Afghanistan-Turkmenistan border, until it enters Turkmenistan where the modern-day Karakum Canal begins. The river's course has been fairly stable along this part of the route throughout recorded history, although it has made many minor deviations, especially further downstream where the land becomes flatter. This part of the river was the Bactrian heartland in antiquity.

The rest of the river's route – mainly through Turkmenistan, but also hugging the Uzbek border in sections, and finally petering out in Uzbekistan – traverses the flat, arid Karakum Desert. The course and strength of the river down here has changed constantly over the centuries; for this reason, the Oxus has earned the nickname "the mad river". In ancient times, the Uzboy river branched off from the Oxus in northern Turkmenistan, and ran west across the desert until (arguably) emptying into the Caspian Sea. However, the strength of the Uzboy gradually lessened, until the river completely perished approximately 400 years ago. It appears that the Uzboy was considered part of the Oxus (and was given no name of its own) by many ancient geographers.

The Oxus proper breaks up into an extensive delta once in Uzbekistan; and for most of recorded history, it emptied into the Aral Sea. However, due to an aggressive Soviet-initiated irrigation campaign since the 1950s (the culmination of centuries of Russian planning and dreaming), the Oxus delta has rescinded significantly, and the river's waters fizzle out in the desert before reaching the sea. This is one of the major causes of the death of the Aral Sea, one of the worst environmental disasters on the planet.

Although geographically separate, the nearby Murghab river is also an important part of the cultural and archaeological story of the Oxus region (its lower reaches in modern-day Turkmenistan, at least). From its confluence with the Kushk river, the Murghab meanders gently down through semi-arid lands, before opening into a large delta that fans out optimistically into the unforgiving Karakum desert. The Murghab delta was in ancient times the heartland of Margiana, an advanced civilisation whose heyday largely predates that of Bactria, and which is home to some of the most impressive (and under-appreciated) archaeological sites in the region.

I won't be covering it in this article, as it's a whole other landscape and a whole lot more history; nevertheless, I would be remiss if I failed to mention the "sister" of the Oxus, the Syr Darya river, which was in antiquity known by its Greek name as the Jaxartes, and which is the other major artery of Central Asia. The source of the Jaxartes is (according to some) not far from that of the Oxus, high up in the Pamir mountains; from there, it runs mainly north-west through Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and then (for more than half its length) Kazakhstan, before approaching the Aral Sea from the east. Like the Oxus, the present-day Jaxartes also peters out before reaching the Aral; and since these two rivers were formerly the principal water sources of the Aral, that sea is now virtually extinct.

Hyrcania

Having finished tracing the rivers' paths from the mountains to the desert, I will now – Much like the documentary – explore the region's ancient realms the other way round, beginning in the desert lowlands.

The heartland of Hyrcania (more often absorbed into a map of ancient Parthia, than given its own separate mention) – in ancient times just as in the present-day – is Golestan province, Iran, which is a fertile and productive area on the south-west shores of the Caspian. This part of Hyrcania is actually outside of the Oxus region, and so falls off this article's radar. However, Hyrcania extended north into modern-day Turkmenistan, reaching the banks of the then-flowing Uzboy river (which was ambiguously referred to by Greek historians as the "Ochos" river).

Settlements along the lower Uzboy part of Hyrcania (which was on occasion given a name of its own, Nesaia) were few. The most notable surviving ruin there is the Igdy Kala fortress, which dates to approximately the 4th century BCE, and which (arguably) exhibits both Parthian and Chorasmian influence. Very little is known about Igdy Kala, as the site has seldom been formally studied. The question of whether the full length of the Uzboy ever existed remains unresolved, particularly regarding the section from Sarykamysh Lake to Igdy Kala.

By including Hyrcania in the Oxus region, I'm tentatively siding with those that assert that the "greater Uzboy" did exist; if it didn't (i.e. if the Uzboy finished in Sarykamysh Lake, and if the "lower Uzboy" was just a small inlet of the Caspian Sea), then the extent of cultural interchange between Hyrcania and the actual Oxus realms would have been minimal. In the documentary, narrator David Adams is quite insistent that the Oxus was connected to the Caspian in antiquity, making frequent reference to the works of Patrocles; while this was quite convenient for the documentary's hypothesis that the Oxo-Caspian was a major trade route, the truth is somewhat less black-and-white.

Chorasmia

North-east of Hyrcania, crossing the lifeless Karakum desert, lies Chorasmia, better known for most of its history as Khwarezm. Chorasmia lies squarely within the Oxus delta; although the exact location of its capitals and strongholds has shifted considerably over the centuries, due to political upheavals and due to changes in the delta's course. In antiquity (particularly in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE), Chorasmia was a vassal state of the Achaemenid Persian empire, much like the rest of the Oxus region; the heavily Persian-influenced language and culture of Chorasmia, which can still be faintly observed in modern times, harks back to this era.

This region was strongest in medieval times, and its medieval capital at the present-day ghost city of Konye-Urgench – known in its heyday as Gurganj – was Chorasmia's most significant seat of power. Gurganj was abandoned in the 16th century CE, when the Oxus changed course and left the once-fertile city and surrounds without water.

It's unknown exactly where antiquity-era Chorsamia was centred, although part of the ruins of Kyrk Molla at Gurganj date back to this period, as do part of the ruins of Itchan Kala in present-day Khiva (which was Khwarezm's capital from the 17th to the 20th centuries CE). Probably the most impressive and best-preserved ancient ruins in the region, are those of the Ayaz Kala fortress complex, parts of which date back to the 4th century BCE. There are numerous other "Kala" (the Chorasmian word for "fortress") nearby, including Toprak Kala and Kz'il Kala.

One of the less-studied sites – but by no means a less significant site – is Dev-kesken Kala, a fortress lying due west of Konye-Urgench, on the edge of the Ustyurt Plateau, overlooking the dry channel of the former upper Uzboy river. Much like Konye-Urgench (and various other sites in the lower Oxus delta), Dev-kesken Kala was abandoned when the water stopped flowing, in around the 16th century CE. The city was formerly known as Vazir, and it was a thriving hub of medieval Khwarezm. Also like other sites, parts of the fortress date back to the 4th century BCE.

Image source: Karakalpak: Devkesken qala and Vazir.

I should also note that Dev-kesken Kala was one of the most difficult archaeological sites (of all the sites I'm describing in this article) to find information online for. I even had to create the Dev-Kesken Wikipedia article, which previously didn't exist (my first time creating a brand-new page there). The site was also difficult to locate on Google Earth (should now be easier, the co-ordinates are saved on the Wikipedia page). The site is certainly under-studied and under-visited, considering its distinctive landscape and its once-proud history; however, it is remote and difficult to access, and I understand that this Uzbek-Turkmen frontier area is also rather unsafe, due to an ongoing border dispute.

Margiana

South of Chorasmia – crossing the Karakum desert once again – one will find the realm that in antiquity was known as Margiana (although that name is simply the hellenised version of the original Persian name Margu). Much like Chorasmia, Margiana is centred on a river delta in an otherwise arid zone; in this case, the Murghab delta. And like the Oxus delta, the Murghab delta has also dried up and rescinded significantly over the centuries, due to both natural and human causes. Margiana lies within what is present-day southern Turkmenistan.

Although the Oxus doesn't run through Margiana, the realm is nevertheless part of the Oxus region (more surely so than Hyrcania, through which a former branch of the Oxus arguably runs), for a number of reasons. Firstly, it's geographically quite close to the Oxus, with only about 200km of flat desert separating the two. Secondly, the Murghab and the Oxus share many geographical traits, such as their arid deltas (as mentioned above), and also their habit of frequently and erratically changing course. Lastly, and most importantly, there is evidence of significant cultural interchange between Margiana and the other Oxus realms throughout civilised history.

The political centre of Margiana – in the antiquity period and for most of the medieval period, too – was the city of Merv, which was known then as Gyaur Kala (and also briefly by its hellenised name, Antiochia Margiana). Today, Merv is one of the largest and best-preserved archaeological sites in all the Oxus region, although most of the visible ruins are medieval, and the older ruins still lie largely buried underneath. The site has been populated since at least the 5th century BCE.

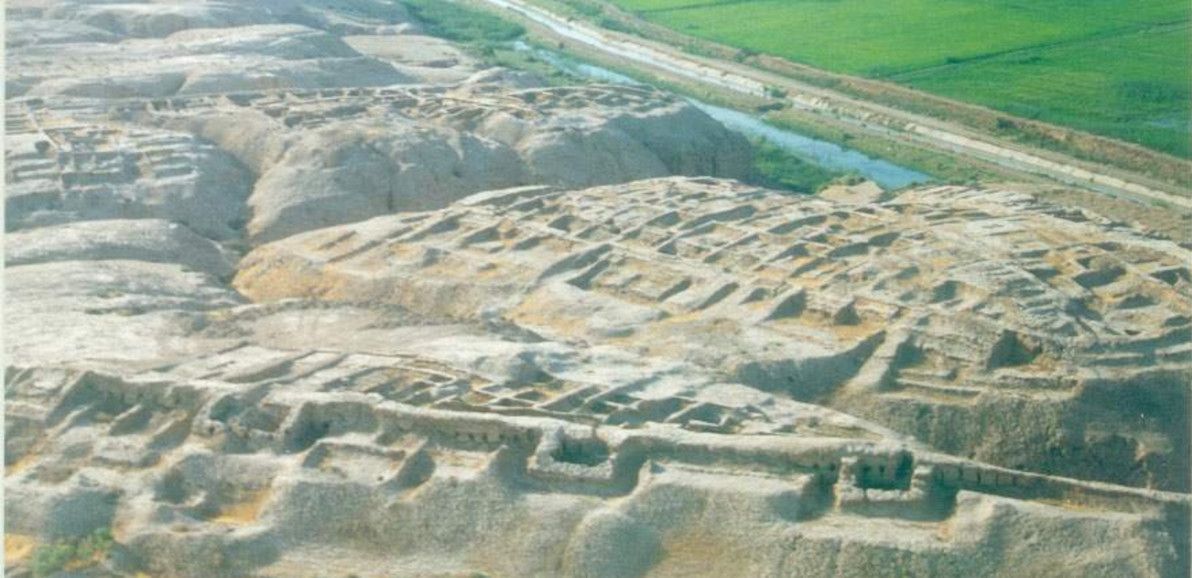

Although Merv was Margiana's capital during the Persian and Greek periods, the site of most significance around here is the far older Gonur Tepe. The site of Gonur was completely unknown to modern academics until the 1970s, when the legendary Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi discovered it (Sarianidi sadly passed away less than a year ago, aged 84). Gonur lies in what is today the parched desert, but what was – in Gonur's heyday, in approximately 2,000 BCE – well within the fertile expanse of the then-greater Murghab delta.

Image source: Boskawola.

Gonur was one of the featured sites in the documentary series – and justly so, because it's the key site of the so-called Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. It's also a prime example of a "forgotten realm" in the region: to this day, few tourists and journalists have ever visited it (David Adams and his crew were among those that have made the arduous journey); and, apart from Sarianidi (who dedicated most of his life to studying Gonur and nearby ruins), few archaeologists have explored the site, and insufficient effort is being made by authorities and by academics to preserve the crumbling ruins. All this is a tragedy, considering that some have called for bronze-age Margiana to be added to the list of the classic "cradles of civilisation", which includes Egypt, Babylon, India, and China.

There are many other ruins in Margiana that were part of the bronze-age culture centred in Gonur. One of the other more promiment sites is Altyn Tepe, which lies about 200km south-west of Gonur, still within Turkmenistan but close to the Iranian border. Altyn Tepe, like Gonur, reached its zenith around 2,000 BCE; the site is characterised by a large Babylon-esque ziggurat. Altyn Tepe was also studied extensively by Sarianidi; and it too has been otherwise largely overlooked during modern times.

Sogdiana

Crossing the Karakum desert again (for the last time in this article) – heading north-east from Margiana – and crossing over to the northern side of the Oxus river, one may find the realm that in antiquity was known as Sogdiana (or Sogdia). Sogdiana principally occupies the area that is modern-day southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan.

The Sogdian heartland is the fertile valley of the Zeravshan river (old Persian name), which was once known by its Greek name, as the Polytimetus, and which has also been called the Sughd, in honour of its principal inhabitants (modern-day Tajikistan's Sughd province, through which the river runs, likewise honours them).

The Zeravshan's source is high in the mountains near the Tajik-Kyrgyz border, and for its entire length it runs west, passing through the key ancient Sogdian cities of Panjakent, Samarkand (once known as Maracanda), and Bukhara (which all remain vibrant cities to this day), before disappearing in the desert sands approaching the Uzbek-Turkmen border. The Zeravshan probably reached the Oxus and emptied into it – once upon a time – near modern-day Türkmenabat, which in antiquity was known as Amul, and in medieval times as Charjou. For most of its history, Amul lay just beyond the frontiers of Sogdiana, and it was the crossroads of all the principal realms of the Oxus region mentioned in this article.

Although Sogdiana is an integral part of the Oxus region, and although it was a dazzling civilisation in antiquity (indeed, it was arguably the most splendid of all the Oxus realms), I'm only mentioning it in this article for completeness, and I will refrain from exploring its archaeology in detail. (You may also have noted that the Zeravshan river and the Sogdian cities are missing from my custom map of the region). This is because I don't consider Sogdiana to be "forgotten", in anywhere near the sense that the other realms are "forgotten".

The key Sogdian sites – particularly Samarkand and Bukhara, which are both today UNESCO-listed – enjoy international fame; they have been studied intensively by modern academics; and they are the biggest tourist attractions in all of Central Asia. Apart from Sogdiana's prominence in Silk Road history, and its impressive and well-preserved architecture, the relative safety and stability of Uzbekistan – compared with its fellow Oxus-region neighbours Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan – has resulted in the Sogdian heartland receiving the attention it deserves from the curious modern world.

Also – putting aside its "not forgotten" status – the partial exclusion (or, perhaps more accurately, the ambivalent inclusion) of Sogdiana from the Oxus region has deep historical roots. Going back to Achaemenid Persian times, Sogdiana was the extreme northern frontier of Darius's empire. And when the Greeks arrived and began to exert their influence, Sogdiana was known as Transoxiana, literally meaning "the land across the Oxus". Thus, from the point of view of the two great powers that dominated the region in antiquity – the Persians and the Greeks – Sogdiana was considered as the final outpost: a buffer between their known, civilised sphere of control; and the barbarous nomads who dwelt on the steppes beyond.

Bactria

Finally, after examining the other realms of the Oxus region, we come to the land that was the region's showpiece in the antiquity period: Bactria. The Bactrian heartland can be found south of Sogdiana, separated from it by the (relatively speaking) humble Chul'bair mountain range. Bactria occupies a prime position along the Oxus river: that is, it's the first section lying downstream of overly-rugged terrain; and it's upstream enough that it remains quite fertile to this day, although it's significantly less fertile than it was millennia ago. Bactria falls principally within modern-day northern Afghanistan; but it also encroaches into southern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

Historians know more about antiquity-era Bactria than they do about the rest of the Oxus region, primarily because Bactria was better incorporated into the great empires of that age than were its neighbours, and therefore far more written records of Bactria have survived. Bactria was a semi-autonomous satrapy (province) of the Persian empire since at least the 6th century BCE, although it was probably already under Persian influence well before then. It was conquered by Alexander the Great in 328 BCE (after he had already marched through Sogdiana the year before), thus marking the start of Greco-Bactrian rule, making Bactria the easternmost hellenistic outpost of the ancient world.

However, considering its place in the narrative of these empires, and considering its being recorded by both Persian and Greek historians, surprisingly little is known about the details of ancient Bactria today. This is why the documentary was called "Alexander's Lost World". Much like its neighbours, the area comprising modern-day Bactria is relatively seldom visited and seldom studied, due to its turbulent recent history.

The first archaeological site that I'd like to discuss in this section is that of Kampyr Tepe, which lies on the northern bank of the Oxus (putting it within Uzbek territory), just downstream from modern-day Termez. Kampyr Tepe was constructed around the 4th century BCE, possibly initially as a garrison by Alexander's forces. It was a thriving city for several centuries after that. It would have been an important defensive stronghold in antiquity, lying as it does near the western frontier of Bactria proper, not far from the capital, and affording excellent views of the surrounding territory.

Image source: rusanoff – Photo of Kampyrtepa.

There is evidence that a number of different religious groups co-existed peacefully in Kampyr Tepe: relics of Hellenism, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism from similar time periods have been discovered here. The ruins themselves are in good condition, especially considering the violence and instability that has affected the site's immediate surroundings in recent history. However, the reason for the site's admirable state of preservation is also the reason for its inaccessibility: due to its border location, Kampyr Tepe is part of a sensitive Uzbek military-controlled zone, and access is highly restricted.

The capital of Bactria was the grand city of Bactra, the location of which is generally accepted to be a circular plateau of ruins touching the northern edge of the modern-day city of Balkh. These lie within the delta of the modern-day Balkh river (once known as the Bactrus river), about 70km south of where the Oxus presently flows. In antiquity, the Bactrus delta reached the Oxus and fed into it; but the modern-day Balkh delta (like so many other deltas mentioned in this article) fizzles out in the sand.

Today, the most striking feature of the ruins is the 10km-long ring of thick, high walls enclosing the ancient city. Balkh is believed to have been inhabited since at least the 27th century BCE, although most of the archaeological remains only date back to about the 4th century BCE. The ruins at Balkh are currently on UNESCO's tentative World Heritage list. It's likely that the plateau at Balkh was indeed ancient Bactra; however, this has never been conclusively proven. Modern archaeologists barely had any access to the site until 2003, due to decades of military conflict in the area. To this day, access continues to be highly restricted, for security reasons.

Image source: Hazara Association of UK.

Bactria was an important centre of Zoroastianism, and Bactra is one of (and is the most likely of) several contenders claiming to be the home of the mythical prophet Zoroaster. Tentatively related to this, is the fact that Bactra was also (possibly) once known as Zariaspa. A few historians have gone further, and have suggested that Bactra and Zariaspa were two different cities; if this is the case, then a whole new can of worms is opened, because it begs a multitude of further questions. Where was Zariaspa? Was Bactra at Balkh, and Zariaspa elsewhere? Or were Bactra and Zariaspa actually the same city… but located elsewhere?

Based on the theory of Ptolemy (and perhaps others), in the documentary David Adams strongly hypothesises that: (a) Bactra and Zariaspa were twin cities, next to each other; (b) the twin-city of Bactra-Zariaspa was located somewhere on the Oxus north of Balkh (he visits and proposes such a site, which I believe was somewhere between modern-day Termez and Aiwanj); and (c) this site, rather than Balkh, was the capital of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom that followed Alexander's conquest. While this is certainly an interesting hypothesis – and while it's true that there hasn't been nearly enough excavation or analysis done in modern times to rule it out – the evidence and the expert opinion, as it stands today, would suggest that Adams's hypothesis is wrong. As such, I think that his assertion of "the lost city of Bactra-Zariaspa" lying on the Oxus, rather than in the Bactrus delta, was stated rather over-confidently and with insufficient disclaimers in the documentary.

Upper Bactria

Although not historically or culturally distinct from the Bactrian heartland, I'm analysing "Upper Bactria" (i.e. the part of Bactria upstream of modern-day Balkh province) separately here, primarily to maintain structure in this article, but also because this farther-flung part of the realm is geographically quite rugged, in contrast to the heartland's sweeping plains.

First stop in Upper Bactria is the archaeological site of Takhti Sangin. This ancient ruin can be found on the Tajik side of the border; and since it's located at almost the exact spot where the Panj and Vakhsh rivers meet to become the Oxus, it could also be said that Takhti Sangin is the last site along the Oxus proper that I'm examining. However, much like the documentary, I'll be continuing the journey further upstream to the (contested) "source of the Oxus".

Image source: MATT: From North to South.

The principal structure at Takhti Sangin was a large Zoroastrian fire temple, which in its heyday boasted a pair of constantly-burning torches at its main entrance. Most of the remains at the site date back to the 3rd century BCE, when it became an important centre in the Greco-Bactrian kingdom (and when it was partially converted into a centre of Hellenistic worship); but the original temple is at least several centuries older than this, as attested to by various Achaemenid Persian-era relics.

Takhti Sangin is also the place where the famous "Oxus treasure" was discovered in the British colonial era (most of the treasure can be found on display at the British Museum to this day). In the current era, visitor access to Takhti Sangin is somewhat more relaxed than is access to the Bactrian sites further downstream (mentioned above) – there appear to be tour operators in Tajikistan running regularly-scheduled trips there – but this is also a sensitive border area, and as such, access is controlled by the Tajik military (who maintain a constant presence). Much like the sites of the Bactrian heartland, Takhti Sangin has been studied only sporadically by modern archaeologists, and much remains yet to be clarified regarding its history.

Moving further upstream, to the confluence of the Panj and Kokcha rivers, one reaches the site of Ai-Khanoum (meaning "Lady Moon" in modern Uzbek), which is believed (although not by all) to be the legendary city that was known in antiquity as Alexandria Oxiana. This was the most important Greco-Bactrian centre in Upper Bactria: it was built in the 3rd century BCE, and appears to have remained relatively vibrant for several centuries thereafter. It's also the site furthest upstream on the Oxus, for which there is significant evidence to indicate a Greco-Bactrian presence. It's a unique site within the Oxus region, in that it boasts the typical urban design of a classical Greek city; it's virtually "a little piece of Greece" in Central Asia. It even housed an amphitheatre and a gymnasium.

Ai-Khanoum certainly qualifies as a "lost" city: it was unknown to all save some local tribespeople, until the King of Afghanistan chanced upon it during a hunting trip in 1961. Due primarily to the subsequent Afghan-Soviet war, the site has been poorly studied (and also badly damaged) since then. In the documentary, it's explained how (and illustrated with some impressive 3D animation) – according to some – the Greco-Bactrian city was built atop the ruins of an older city, probably of Persian origin, which was itself once a dazzling metropolis. The documentary also indicates that access to Ai-Khanoum is currently tricky, and must be coordinated with the Afghan military; the site itself is also difficult to physically reach, as it's basically an island amongst the rivers that converge around it, depending on seasonal fluctuations.

The final site that I'd like to discuss regarding the realm of Bactria, is that of Sar-i Sang (a name meaning "place of stone"). At this particularly remote spot in the mountains of Badakhstan, there barely exists a town, neither today nor in ancient times. The nearest settlement of any size is modern-day Fayzabad, the provincial capital. From Ai-Khanoum, the Kokcha river winds upstream and passes through Fayzabad; and from there, the Kokcha valley continues its treacherous path up into the mountains, with Sar-i Sang located about 100km's south of Fayzabad.

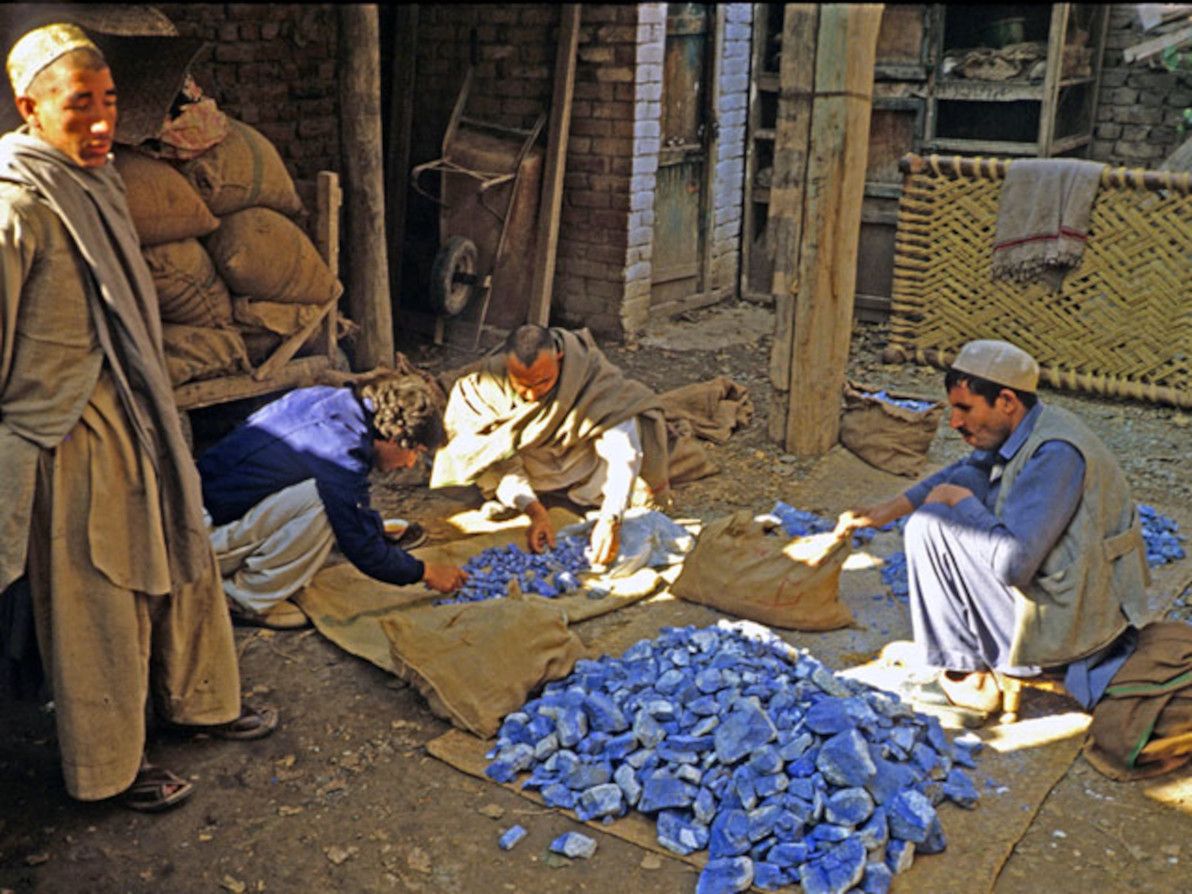

Sar-i Sang is not a town, it's a mine: at an estimated 7,000 years of age, it's believed to be the oldest continuously-operating mine in the world. Throughout recorded history, people have come here seeking the beautiful precious stone known as lapis lazuli, which exists in veins of the hillsides here in the purest form and in the greatest quantity known on Earth.

Image source: Jewel Tunnel Imports: Lapis Lazuli.

Although Sar-i Sang (also known as Darreh-Zu) is quite distant from all the settlements of ancient Bactria (and quite distant from the Oxus), the evidence suggests that throughout antiquity the Bactrians worked the mines here, and that lapis lazuli played a significant role in Bactria's international trade. Sar-i Sang lapis lazuli can be found in numerous famous artifacts of other ancient empires, including the tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt. Sources also suggest that this distinctive stone was Bactria's most famous export, and that it was universally associated with Bactria, much like silk was associated with China.

The Wakhan

Having now discussed the ancient realms of the Oxus from all the way downstream in the hot desert plains, there remains only one segment of this epic river left to explore: its source far upstream. East of Bactria lies one of the most inaccessible, solitary, and unspoiled places in the world: the Wakhan Corridor. Being the place where a number of very tall mountain ranges meet – among them the Pamirs, the Hindu Kush, and the Karakoram – the Wakhan has often been known as "The Roof of the World".

The Wakhan today is a long, slim "panhandle" of territory within Afghanistan, bordered to the north by Tajikistan, to the south by Pakistan, and to the east by China. This distinctive borderline was a colonial-era invention, a product of "The Great Game" played out between Imperial Russia and Britain, designed to create a buffer zone between these powers. Historically, however, the Wakhan has been nomadic territory, belonging to no state or empire, and with nothing but the immensity of the surrounding geography serving as its borders (as it continues to be on the ground to this day). The area is also miraculously bereft of the scourges of war and terrorism that have plagued the rest of Afghanistan in recent years.

Image source: Geoffrey Degens: Wakhan Valley at Sarhad.

Much like the documentary, my reasons for discussing the Wakhan are primarily geographic ones. The Wakhan is centred around a single long valley, whose river – today known as the Panj, and then higher up as the Wakhan river – is generally recognised as the source of the Oxus. It's important to acknowledge this high-altitude area, which plays such an integral role in feeding the river that diverse cultures further downstream depend upon, and which has fuelled the Oxus's long and colourful history.

There are few significant archaeological sites within the Wakhan. The ancient Kaakha fortress falls just outside the Wakhan proper, at the extreme eastern-most extent of the influence of antiquity-era kingdoms in the Oxus region. The only sizeable settlement in the Wakhan itself is the village of Sarhad, which has been continuously inhabited for millennia, and which is the base of the unique Wakhi people, who are the Wakhan's main tribe (Sarhad is also where the single rough road along the Wakhan valley ends). Just next to Sarhad lies the Kansir fort, built by the Tibetan empire in the 8th century CE, a relic of the battle that the Chinese and Tibetan armies fought in the Wakhan in the year 747 CE (this was probably the most action that the Wakhan has ever seen in its history).

Close to the very spot where the Wakhan river begins is Baza'i Gonbad (or Bozai Gumbaz, in Persian "domes of the elders"), a collection of small, ancient mud-brick domes about which little is known. As there's nothing else around for miles, they are occasionally used to this day as travellers' shelters. They are believed to be the oldest structures in the Wakhan, but it's unclear who built them (it was probably one of the nomadic Kyrgyz tribes that roam the area), or when.

Image source: David Adams Films: Bozai Gumbaz.

Regarding which famous people have visited the Wakhan throughout history: it appears almost certain that Marco Polo passed through the Wakhan in the 13th century CE, in order to reach China; and a handful of other Europeans visited the Wakhan in the subsequent centuries (and it's almost certain that the only "tourists" to ever visit the Wakhan are those of the past century or so). In the documentary, David Adams suggests repeatedly in the final episode (that in which he journeys to the Wakhan) that Alexander – either the man himself, or his legions – not only entered the Wakhan Corridor, but even crossed one of its high passes over to Pakistan. I've found no source to clearly corroborate this claim; and after posing the question to a forum of Alexander-philes, it appears quite certain that neither Alexander nor his legions ever set foot in the Wakhan.

Conclusion

So, there you have it: my humble overview of the history of a region ruled by rivers, empires, and treasures. As I've emphasied throughout this article, the Oxus region is most lamentably a neglected and under-investigated place, considering its colourful history and its rich tapestry of cultures and landscapes. My aim in writing this piece is simply to inform anyone else who may be interested, and to better preserve the region's proud legacy.

I must acknowledge and wholeheartedly thank David Adams and his team for producing the documentary Alexander's Lost World, which I have referred to throughout this article, and whose material I have re-analysed as the basis of my writings here. The series has been criticised by history buffs for its various inaccuracies and unfounded claims; and I admit that I too, in this article, have criticised it several times. However, despite this, I laud the series' team for producing a documentary that I enjoyed immensely, and that educated me and inspired me to research the Oxus region in-depth. Like the documentary, this article is about rivers and climate change as the primary forces of the region, and Alexander the Great (along with other famous historical figures) is little more than a sidenote to this theme.

I am by no means an expert on the region, nor have I ever travelled to it (I have only "vicariously" travelled there, by watching the documentary and by writing this article!). I would love to someday set my own two feet upon the well-trodden paths of the Oxus realms, and to see these crumbling testaments to long-lost g-ds and kings for myself. For now, however, armchair history blogging will have to suffice.

]]>I spent a bit of time recently, hunting for sets of data that could answer these questions in an expansive and meaningful way. And I'm optimistic that what I've come up with satisfies both of those things: in terms of expansive, I've got stats (admittedly of varying quality) for most of the film-watching world; and in terms of meaningful, I'm using box office admission numbers, which I believe are the most reliable international measure of film popularity.

So, without further ado, here are the stats that I've come up with:

| Country | Admissions (millions) | US admissions (percent of total) | EU admissions (percent of total) | Local admissions (percent of total) | Other admissions (percent remainder) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India |

2,900.0

|

6.0%

|

0.8%

|

92.0%

|

1.2%

|

| US |

1,364.0

|

91.5%

|

7.2%

|

n/a

|

1.3%

|

| China |

217.8

|

38.0%

|

4.0%

|

56.6%

|

1.4%

|

| France |

200.9

|

49.8%

|

50.2%

|

n/a

|

0.0%

|

| Mexico |

178.0

|

90.0%

|

1.0%

|

7.5%

|

1.5%

|

| UK |

173.5

|

77.0%

|

21.5%

|

n/a

|

1.5%

|

| Japan |

169.3

|

38.0%

|

2.0%

|

56.9%

|

1.5%

|

| South Korea |

156.8

|

46.0%

|

2.5%

|

48.8%

|

2.7%

|

| Germany |

146.3

|

65.0%

|

34.4%

|

n/a

|

0.6%

|

| Russia & CIS |

138.5

|

60.0%

|

12.0%

|

23.9%

|

4.1%

|

| Brazil |

112.7

|

75.0%

|

10.0%

|

14.3%

|

0.7%

|

| Italy |

111.2

|

64.0%

|

29.4%

|

n/a

|

6.6%

|

| Spain |

109.5

|

65.0%

|

32.0%

|

n/a

|

3.0%

|

| Canada |

108.0

|

88.5%

|

8.0%

|

2.8%

|

0.7%

|

| Australia |

90.7

|

84.2%

|

10.0%

|

5.0%

|

0.8%

|

| Philippines |

65.4

|

80.0%

|

4.0%

|

15.0%

|

1.0%

|

| Indonesia |

50.1

|

80.0%

|

4.0%

|

15.0%

|

1.0%

|

| Malaysia |

44.1

|

82.0%

|

4.0%

|

13.7%

|

0.3%

|

| Poland |

39.2

|

70.0%

|

29.5%

|

n/a

|

0.5%

|

| Turkey |

36.9

|

42.0%

|

6.0%

|

50.9%

|

1.1%

|

| Argentina |

33.3

|

76.0%

|

7.0%

|

16.0%

|

1.0%

|

| Netherlands |

27.3

|

65.0%

|

33.4%

|

n/a

|

1.6%

|

| Colombia |

27.3

|

82.0%

|

10.0%

|

4.8%

|

3.2%

|

| Thailand |

27.1

|

60.0%

|

1.0%

|

37.5%

|

1.5%

|

| South Africa |

26.1

|

72.0%

|

10.0%

|

15.0%

|

3.0%

|

| Egypt |

25.6

|

16.0%

|

2.0%

|

80.0%

|

2.0%

|

| Taiwan |

23.6

|

75.0%

|

2.0%

|

22.3%

|

0.7%

|

| Belgium |

22.6

|

60.0%

|

37.9%

|

n/a

|

2.1%

|

| Singapore |

22.0

|

90.0%

|

3.0%

|

3.8%

|

3.2%

|

| Venezuela |

22.0

|

90.0%

|

6.0%

|

0.6%

|

3.4%

|

| Hong Kong |

20.1

|

70.0%

|

3.0%

|

21.0%

|

6.0%

|

Note: this table lists all countries with annual box office admissions of more than 20 million tickets sold. The countries are listed in descending order of number of box office admissions. The primary source for the data in this table (and for this article in general), is the 2010 edition of the FOCUS: World Film Market Trends report, published by the European Audiovisual Observatory.

The Mighty Hollywood

Before I comment on anything else, I must make the point loudly and clearly: Hollywood is still the most significant cinema force in the world, as it has consistently been since the dawn of movie-making over a century ago. There can be no denying that. By every worldwide cinema-going measure, movies from the United States are still No. 1: quantity of box office tickets sold; gross box office profit; and extent of geopolitical box office distribution.

The main purpose of this article, is to present the cinema movements around the world that are competing with Hollywood, and to demonstrate that some of those movements are significant potential competition for Hollywood. I may, at times in this article, tend to exaggerate the capacity of these regional players. If I do, then please forgive me, and please just remind yourself of the cold, harsh reality, that when Hollywood farts, the world takes more notice than when Hollywood's contenders discover life on Mars.

Seriously, Hollywood is mighty

Having made my above point, let's now move on, and have a look at the actual stats that show just how frikkin' invincible the USA's film industry is today:

- The global distribution of US movies is massive: of the 31 countries listed in the table above, 24 see more than 50% of their box office admissions being for US movies.

- The US domestic cinema industry is easily the most profitable in the world, raking in more than US$9 billion annually; and also the most extensive in the world, with almost 40,000 cinema screens across the country (2009 stats).

- The US film industry is easily the most profitable in the world: of the 20 top films worldwide by gross box office, all of them are at least partly Hollywood-produced; and of those, 13 are 100% Hollywood-produced.

Cinéma Européen

In terms of global distribution, and hence also in terms of global social and cultural impact, European movies quite clearly take the lead, after Hollywood (of course). That's why, in the table above, the only two film industries whose per-country global box office admissions I've listed, are those of the United States and of the European Union. The global distribution power of all the other film industries is, compared to these two heavyweights, negligible.

Within the EU, by far the biggest film producer — and the most successful film distributor — is France. This is nothing new: indeed, the world's first commercial public film screening was held in Paris, in 1895, beating New York's début by a full year. Other big players are Germany, Spain, Italy, and the UK. While the majority of Joe Shmoe cinema-goers worldwide have always craved the sex, guns and rock 'n' roll of Hollywood blockbusters, there have also always been those who prefer a more cultured, refined and sophisticated cinema experience. Hence, European cinema is — while not the behemoth that is Hollywood — strong as ever.

France is the only country in Europe — or the world — where European films represent the majority of box office admissions; and even in France, they just scrape over the 50% mark, virtually tied with Hollywood admissions. In the other European countries listed in the table above (UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland, Netherlands, and Belgium), EU admissions make up around 30-35% of the market, with American films taking 60-75% of the remaining share. In the rest of the world, EU admissions don't make it far over the 10% mark; although their share remains significant worldwide, with 24 of the 31 countries in the table above having 3% or more EU admissions.

Oh My Bollywood!

You may have noticed that in the table, the US is not first in the list. That's because the world's largest cinema-going market (in terms of ticket numbers, not gross profit) is not the US. It's India. Over the past several decades, Bollywood has risen substantially, to become the second-most important film industry in the world (i.e. it's arguably more important than the European industry).

India has over 1.2 billion people, giving it the second-largest population in the world (after China). However, Indians love cinema much more than the Chinese do. India has for quite some time been the world's No. 1 producer of feature films. And with 2.9 billion box office admissions annually, the raw cinema-going numbers for India are more than double those of the US, which follows second worldwide.

Apart from being No. 1 in domestic box office admissions, India also has the highest percentage of admissions for local films, and the lowest percentage of admissions for US films, in the world. That means that when Indians go to the cinema, they watch more local movies, and less American movies, than any other people in the world (exactly what the social and cultural implications of that are, I leave for another discussion — perhaps better analysed in a PhD thesis than in a blog post!). That also gives Bollywood the No. 2 spot for international box office admissions.

However, massive as Bollywood's presence and its influence is domestically within India (and in the rest of South Asia), its global reach is pretty slim. Bollywood's No. 2 spot for international box office admissions, stems 99% from its domestic admissions. The vast majority of Bollywood movies are never even shipped outside of the region, let alone screened in cinemas. A significant number are also filmed in the Hindi language, and are never dubbed or subtitled in English (or any other languages), due to lack of an international market.

There are some exceptions. For example, a number of Bollywood films are distributed and screened in cinemas in the UK, targeting the large Indian community there (the number of films is relatively small compared to the size of the Bollywood industry, but it's a significant number within the UK cinema market). However, despite its growing international fame, Bollywood remains essentially a domestic affair.

The rest of the world has yet to truly embrace the lavish psychedelic costumes; the maximum interval of six minutes between twenty-minute-long, spontaneous, hip-swinging, sari-swirling song-and-dance routines; or the idea that the plot of every movie should involve a poor guy falling in love with a rich girl whose parents refuse for them to marry (oh, and of course there must also be a wedding, and it must be the most important and extravagent scene of the movie). Bollywood — what's not to love?

Nollywood, anyone?

We're all familiar with Bollywood… but have you heard of Nollywood? It's the film industry of Nigeria. And, in case you didn't know, in the past decade or so Nollywood has exploded from quite humble beginnings, into a movement of epic proportions and of astounding success. In 2009, Nollywood rose up to become the No. 2 producer of feature films in the world (second only to the Indian industry, and pushing Hollywood down to third place).

However, you may have noticed that Nigeria isn't in the table above at all. That's because cinema screens in Nigeria are few and far between, and almost all Nollywood films are released straight to home media (formerly VHS, these days DVD). So, Nollywood is an exceptional case study here, because the focus of this article is to measure the success of film industries by box office admissions; and yet Nollywood, which has rapidly become one of the most successful film industries in the world, lacks almost any box office admissions whatsoever.

There are few hard statistics available for distribution of films within Nigeria (or in most of the rest of Africa), in terms of box office admissions, DVD sales (with almost all being sold in ramshackle markets, and with many being pirated copies), or anything else. However, the talk of the town is that the majority of movies watched in Nigeria, and in many other countries in Africa, are local Nollywood flicks. In Nigeria itself, the proportion of local-vs-Hollywood film-watching may even be reaching Indian levels, i.e. more than 90% of viewings being of local films — although it's impossible to give any exact figures.

Nollywood's distribution reach is pretty well limited to domestic Nigeria, and the surrounding African regions. Bollywood boasts a significantly greater international distribution… and Bollywood's reach ain't amazing, either. The low-budget production and straight-to-disc distribution strategies of Nollywood have proved incredibly successful locally. However, this means that most Nollywood movies aren't even suitable for cinema projection without serious editing (in terms of technology and cinematography), and this has probably been a factor in limiting Nollywood's growth in other markets, where traditional box office distribution is critical to success.

East Asian cinema

The film industries of the Orient have always been big. In particular, the industries of China and Japan, respectively, are each only slightly behind Hollywood in number of feature films produced annually (and Korea is about on par with Italy). Many East Asian film industries enjoy considerable local success, as evidenced in the table above, where several Asian countries are listed as having a significant percentage of local box office admissions (in China, Japan and Korea, local films sweep away 50% or more of the box office admissions).

Much like Bollywood, the film industries of many East Asian countries have often fallen victim to cliché and "genre overdose". In China and Hong Kong, the genre of choice has long been martial arts, with Kung Fu movies being particularly popular. In Japan and Korea, the most famous genre traditionally has been horror, and in more recent decades (particularly in Japan), the anime genre has enjoyed colossal success.

East Asian film is arguably the dominant cultural film force within the region (i.e. dominant over Hollywood). It's also had a considerable influence on the filmmaking tradition of Hollywood, with legends such as Japan's Akira Kurosawa being cited by numerous veteran Hollywood directors, such as Martin Scorsese.

However, well-established though it is, the international distribution of East Asian films has always been fairly limited. Some exceptional films have become international blockbusters, such as the (mainly) Chinese-made Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). Japanese horror and anime films are distributed worldwide, but they have a cult following rather than a mainstream appreciation in Western countries. When most Westerners think of "Asian" movies, they most likely think of Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee, the majority of whose films were Hollywood productions. Additionally, the international distribution of movies from other strong East Asian film industries, such as those of Thailand and Taiwan, is almost non-existent.

Middle Eastern cinema

The most significant player in Middle Eastern cinema is Egypt, which has a long and glorious film-making tradition. The Egyptian film industry accounts for a whopping 80% of Egypt's domestic box office admissions; and, even more importantly, Egyptian films are exported to the rest of the Arabic-speaking world (i.e. to much of the rest of the Middle East), and (to some extent) to the rest of the Muslim world.

Turkey is also a cinema powerhouse within the Middle East. Turkey's film industry boasts 51% of the local box office admissions, and Turkey as a whole is the largest cinema-going market in the region. The international distribution of Turkish films is, however, somewhat more limited, due to the limited appeal of Turkish-language cinema in other countries.

Although it's not in the table above, and although limited data is available for it, Iran is the other great cinema capital of the region. Iran boasted a particularly strong film industry many decades ago, before the Islamic Revolution of 1979; nevertheless, the industry is still believed to afford significant local market share today.

Also of note is Israel, which is the most profitable cinema-going market in the region after Turkey, and which supports a surprisingly productive and successful film industry (with limited but far-reaching international distribution), given the country's small population.

Other players worldwide

- Russia & CIS. Although US box office admissions dominate these days, the Russian film industry wins almost 25% of admissions. This is very different to the Soviet days, when foreign films were banned, and only state-approved (and highly censored) films were screened in cinemas. Russian movies are mainly distributed within the former Soviet Union region, although a small number are exported to other markets.

- Latin America. The largest markets for box office admissions in the region are Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. Admissions in all of Latin America are majority Hollywood; however, in these "big three", local industries are also still quite strong (particularly in Brazil and Argentina, each with about 15% local admissions; about half that number in more US-dominated Mexico). Local industries aren't as strong as they used to be, but they're still most definitely alive. Latin American films are distributed and screened worldwide, although their reception is limited. There have been some big hits, though, in the past decade: Mexico's Amores Perros (2000); Argentina's Nueve Reinas (2000); and Brazil's Cidade de Deus (2002).

- South Africa. Despite having a fairly large box office admission tally, there's not a whole lot of data available for local market share in the South African film industry. Nevertheless, it is a long-established film-making country, and it continues to produce a reasonable number of well-received local films every year. South Africa distributes films internationally, although generally not with blockbuster success — but there have been exceptions, e.g. Tsotsi (2005).

In summary

If you've made it this far, you must be keen! (And this article must be at least somewhat interesting). Sorry, this has turned out to be a bit longer than average for a thought article; but hey, turns out there are quite a lot of strong film industries around the world, and I didn't want to miss any important ones.

So, yes, Hollywood's reach is still universal, and its influence not in any way or in any place small. But no, Hollywood is not the only force in this world that is having a significant cultural effect, via the medium of the motion picture. There are numerous other film industries today, that are strong, and vibrant, and big. Some of them have been around for a long time, and perhaps they just never popped up on the ol' radar before (e.g. Egypt). Others are brand-new and are taking the world by storm (e.g. Nollywood).

Hollywood claims the majority of film viewings in many countries around the world, but not everywhere. Particularly, on the Indian Subcontinent (South Asia), in the Far East (China, Japan, Korea), and in much of the Middle East (Egypt, Turkey, Iran), the local film industries manage to dominate over Hollywood in this regard. Considering that those regions are some of the most populous in the world, Hollywood's influence may be significantly less than many people like to claim.

But, then again, remember what I said earlier: Hollywood farts, whole world takes notice; film-makers elsewhere discover life on Mars, doesn't even make the back page.

Additional references

]]>Our journey begins in prehistoric times, (arguably) before man even existed in the exact modern anatomical form that all humans exhibit today. It is believed that modern homo sapiens emerged as a distinct genetic species approximately 200,000 years ago, and it is therefore no coincidence that my search for the oldest known evidence of meaningful human communication also brought me to examine this time period. Evidence suggests that at around this time, humans began to transmit and record information in rock carvings. These are also considered the oldest form of human artistic expression on the planet.

From that time onwards, it's been an ever-accelerating roller-coaster ride of progress, from prehistoric forms of media such as cave painting and sculpture, through to key discoveries such as writing and paper in the ancient world, and reaching an explosion of information generation and distribution in the Renaissance, with the invention of the printing press in 1450AD. Finally, the modern era of the past two centuries has accelerated the pace to dizzying levels, beginning with the invention of the photograph and the invention of the telegraph in the early 19th century, and culminating (thus far) with mobile phones and the Internet at the end of the 20th century.

List of communication milestones

I've done some research in this area, and I've compiled a list of what I believe are the most significant forms of communication or devices for communication throughout human history. You can see my list in the table below. I've also applied some categorisation to each item in the list, and I'll discuss that categorisation shortly.

Prehistoric (200,000 BC - 4,000 BC)

| Name | Year | Directionality | Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| rock carving | c. 200,000 BC | down | permanent |

| song, music and dance | between 100,000 BC and 30,000 BC | down or up or lateral | transient |

| language and oration | between 100,000 BC and 30,000 BC | down or up or lateral | transient |

| body art | between 100,000 BC and 30,000 BC | down or up or lateral | transient |

| jewellery | between 100,000 BC and 30,000 BC | down or up or lateral | permanent |

| mythology | between 100,000 BC and 30,000 BC | down | transient |

| cave painting and visual symbols | between 100,000 BC and 30,000 BC | down | permanent |

| sculpture | between 100,000 BC and 30,000 BC | down | permanent |

| pottery | c. 14,000 BC | down | permanent |

| megalithic architecture | c. 4000 BC | down | permanent |

Ancient (3000 BC - 100 AD)

| Name | Year | Directionality | Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| writing | c. 3000 BC | down | permanent |

| metallurgical art and bronze sculpture | c. 3000 BC | down | permanent |

| alphabet | c. 2000 BC | down | permanent |

| drama | c. 500 BC | down or up or lateral | transient |

| paper | c. 100 AD | down | permanent |

Renaissance (1450 AD - 1620)

| Name | Year | Directionality | Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| printing press | 1450 AD | down | permanent |

| printed books | c. 1500 | down | permanent |

| newspapers and magazines | c. 1620 | down | permanent |

Modern (1839 - present)

| Name | Year | Directionality | Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| photograph | 1839 | down or up or lateral | permanent |

| telegraph | 1844 | lateral | permanent |

| telephone | 1876 | lateral | transient |

| phonograph (gramophone) | 1877 | down | permanent |

| movie camera | 1891 | down or up or lateral | permanent |

| film | 1894 | down | permanent |

| radio | 1906 | down | permanent |

| television | 1936 | down | permanent |

| videotape | 1958 | down or up or lateral | permanent |

| cassette tape | 1964 | down or up or lateral | permanent |

| personal computer | 1973 | down or up or lateral | permanent |

| compact disc | 1983 | down | permanent |

| mobile phone | 1991 | lateral | transient |

| internet | 1992 | down or up or lateral | permanent |

Note: pre-modern dates are approximations only, and are based on the approximations of authoritative sources. For modern dates, I have tried to give the date that the device first became available to (and first started to be used by) the general public, rather than the date the device was invented.

Directionality and preservation

My categorisation system in the list above is loosely based on coolscorpio's types of communication. However, I have used the word "directionality" to refer to his "downward, upward and lateral communication"; and I have used the word "preservation" and the terms "transient and permanent" to refer to his "oral and written communication", as I needed terms more generic than "oral and written" for my data set.

Preservation of information is something that we've been thinking about as a species for an awfully long time. We've been able to record information in a permanent, durable form, more-or-less for as long as the human race has existed. Indeed, if early humans hadn't found a way to permanently preserve information, then we'd have very little evidence of their being able to conduct advanced communication at all.

Since the invention of writing, permanent preservation of information has become increasingly widespread*. However, oral language has always been our richest and our most potent form of communication, and it hasn't been until modern times that we've finally discovered ways of capturing it; and even to this very day, our favourite modern oral communication technology — the telephone — remains essentially transient and preserves no record of what passes through it.

Directionality of communication has three forms: from a small group of people (often at the "top") down to a larger group (at the "bottom"); from a large group up to a small one; and between any small groups in society laterally. Human history has been an endless struggle between authority and the masses, and that struggle is reflected in the history of human communication: those at the top have always pushed for the dominance of "down" technologies, while those at the bottom have always resisted, and have instead advocated for more neutral technologies. From looking at the list above, we can see that the dominant communications technologies of the time have had no small effect on the strength of freedom vs authority of the time.

Prehistoric human society was quite balanced in this regard. There were a number of powerful forms of media that only those at the top (i.e. chiefs, warlords) had practical access to. These were typically the more permanent forms of media, such as the paintings on the cave walls. However, oral communication was really the most important media of the time, and it was equally accessible to all members of society. Additionally, societies were generally grouped into relatively small tribes and clans, leaving less room for layers of authority between the top and bottom ranks.

The ancient world — the dawn of human "civilisation" — changed all this. This era brought about three key communications media that were particularly well-suited to a "down" directionality, and hence to empowering authority above the common populace: megalithic architecture (technically pre-ancient, but only just); metallurgy; and writing. Megalithic architecture allowed kings and Pharoahs to send a message to the world, a message that would endure the sands of time; but it was hardly a media accessible to all, as it required armies of labourers, teams of designers and engineers, as well as hordes of natural and mineral resources. Similarly, metallurgy's barrier to access was the skilled labour and the mineral resources required to produce it. Writing, today considered the great enabler of access to information and of global equality, was in the ancient world anything but that, because all but the supreme elite were illiterate, and the governments of the day wanted nothing more but to maintain that status quo.

Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in 1450 AD is generally considered to be the most important milestone in the history of human communication. Most view it purely from a positive perspective: it helped spread literacy to the masses; and it allowed for the spread of knowledge as never before. However, the printing press was clearly a "down" technology in terms of directionality, and this should not be overlooked. To this very day, access to mass printing and distribution services is a privilege available only to those at the very top of society, and it is a privilege that has been consistently used as a means of population control and propaganda. Don't get me wrong, I agree with the general consensus that the positive effects of the printing press far outweigh its downside, and I must also stress that the printing press was an essential step in the right direction towards technologies with more neutral directionality. But essentially, the printing press — the key device that led to the dawn of the Renaissance — only served to further entrench the iron fist of authority that saw its birth in the ancient world.

Modern media technology has been very much a mixed bag. On the plus side, there have been some truly direction-neutral communication tools that are now accessible to all, with photography, video-recording, and sound-recording technologies being the most prominent examples. There is even one device that is possibly the only pure lateral-only communication tool in the history of the world, and it's also become one of the most successful and widespread tools in history: the telephone. On the flip side, however, the modern world's two most successful devices are also the most sinister, most potent "down" directionality devices that humanity has ever seen: TV and radio.

The television (along with film and the cinema, which is also a "down" form of media) is the defining symbol of the 20th century, and it's still going strong into the 21st. Unfortunately, the television is also the ultimate device allowing one-way communication from those at the top of society, to those at the bottom. By its very definition, television is "broadcast" from the networks to the masses; and it's quite literally impossible for it to allow those at the receiving end to have their voices heard. What the Pyramids set in stone before the ancient masses, and what the Gutenberg bibles stamped in ink before the medieval hordes, the television has now burned into the minds of at least three modern generations.

The Internet, as you should all know by now, is changing everything. However, the Internet is also still in its infancy, and the Internet's fate in determining the directionality of communication into the next century is still unclear. At the moment, things look very positive. The Internet is the most accessible and the most powerful direction-neutral technology the world has ever seen. Blogging (what I'm doing right now!) is perhaps the first pure "up" directionality technology in the history of mankind, and if so, then I feel privileged to be able to use it.

The Internet allows a random citizen to broadcast a message to the world, for all eternity, in about 0.001% of the time that it took a king of the ancient world to deliver a message to all the subjects of his kingdom. I think That's Cool™. But the question is: when every little person on the planet is broadcasting information to the whole world, who does everyone actually listen to? Sure, there are literally millions of personal blogs out there, much like this one; and anyone can look at any of them, with just the click of a button, now or 50 years from now (50 years… at least, that's the plan). But even in an information ecosystem such as this, it hasn't taken long for the vast majority of people to shut out all sources of information, save for a select few. And before we know it — and without even a drop of blood being shed in protest — we're back to 1450 AD all over again.

It's a big 'Net out there, people. Explore it.